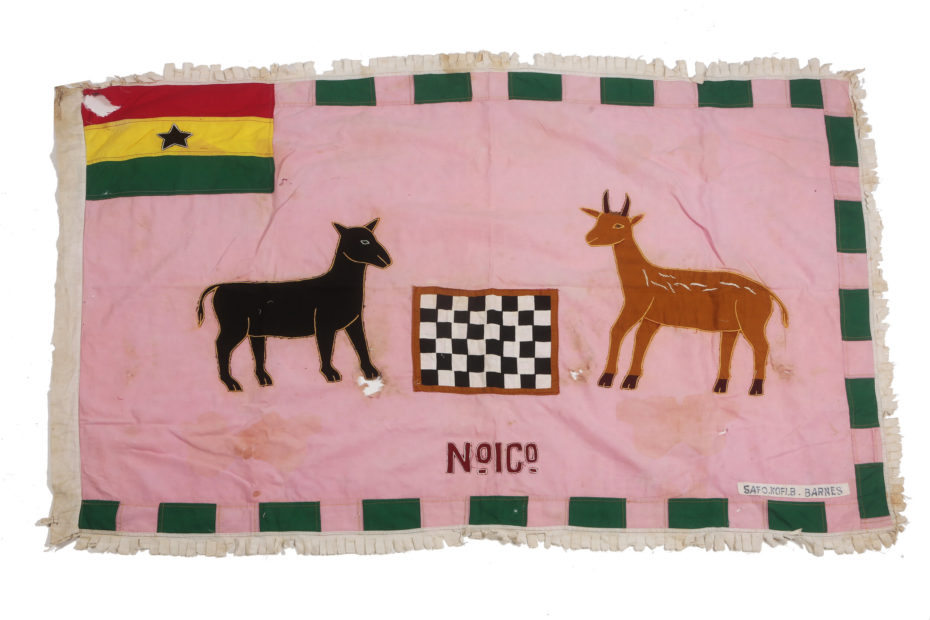

To understand recent Ghanaian history, flags are not a bad place to start. Ghana was under colonial rule by Britain until 1957, but the Portuguese first arrived on the Gold Coast in the 15th century, starting a centuries-long trade industry in goods, arms and slaves. Fabric was a common manufactured material that Europeans brought to Africa, partially influencing the development of Asafo flags, which drew inspiration from naval insignia. Many archival examples include variations of the union jack canton, possibly because leading up to, and during British rule, they saw so much of the heraldry while “trading” with Britain that the Asafo simply incorporated it into their own flag making as a standard symbol of military strength. But the intrigue of the Asafo flags lies in the appliqué animal and human symbols that tell Ghanaian stories and portray local proverbs. The art forms’ longevity — from the arrival of Europeans on the West African coast to the present day — proves the power of textiles and embroidery not only for cultural heritage, but also evolve to explore modern themes and issues.

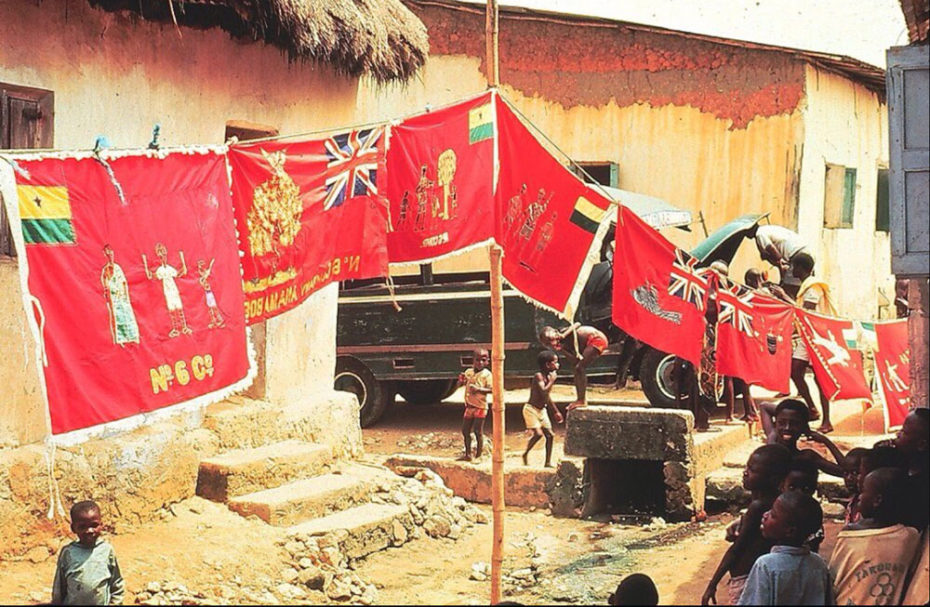

Asafo is derived from the words sa (“war”) and fo (“people”). The flags are regimental flags of the Fante people, an ethnic group that mainly resides in Ghana’s central coastal region who faced conflict with the Ashanti people and their empire, supported by the abundant gold reserves. Asafo companies of European-inspired military groups developed in the absence of a standing army to defend against enemies as well as partake in construction projects, local governing and entertainment activities. The flags became an important part of Fante regalia and would be flown or incorporated into dance movements, representing their strength in battle or insulting rival companies. The flags were also popular at funerals, the annual yam festival and other ceremonies. Every time a new military ruler was appointed, he would have a flag made especially for him and when a chief died, his flag was often left at the shrine in memoriam. They were given such power that some even feared touching them.

Asafo flags also drew inspiration from the Ghanaian Adinkra symbols that convey messages and can form proverbs. A popular image is the Sankofa bird, which has its head pointed backwards, represented learning from the past. But flags also incorporated foreign mythology: The Snite Museum of Art walks through the various symbolism in one of these military flags: including an elephant — a power animal for the Fante people — holding a scale to measure gold and a three-headed flying dragon, a symbol from British tradition and embodying violence and physical ability (gryphons were also commonly depicted).

The flags captured the rapid change of this era, with expanding commerce and infrastructure in towns like Cape Coast. By the time of British colonialization, many of the Asafo flags began to portray the relationship with the imperial ruler, with Union Jacks in the corner and industrial elements like the railroad and trading posts that became slave castles. Many reflected themes of resistance, like an 1863 flag showing men entrapping a large fish in a net, implying that “Europeans erected a strong stone fort (Anomabu Fort), but Africans can use many men to ‘catch’ the fort.”

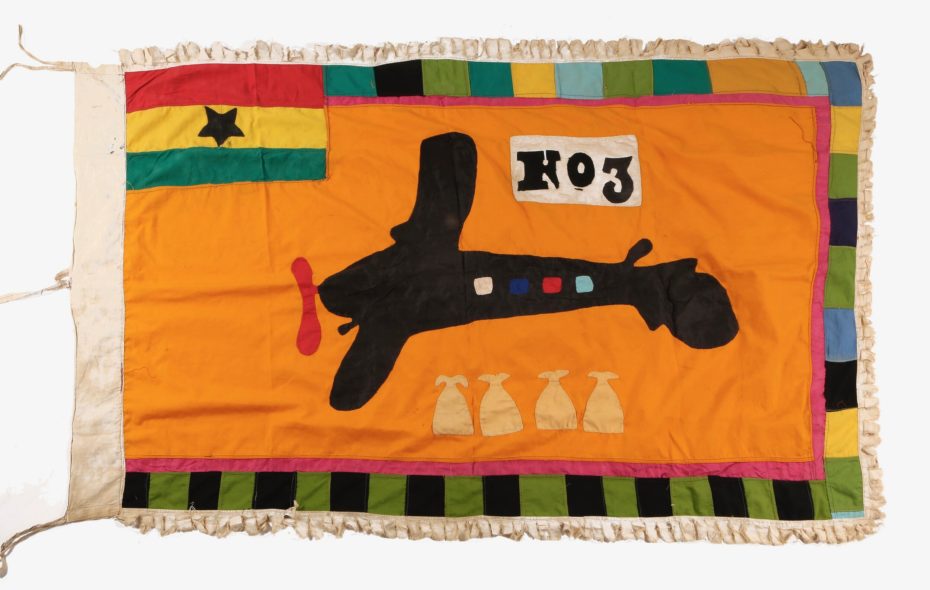

Flags were even used in protests and riots. The political nature of this art led to some being banned and confiscated by local governments, but this only imbued them with more power. During the first World War I, the Fente even made and sold flags showing the British aviation force, with the goal of raising money for reconnaissance planes. The post-war period is sometimes considered the Golden Age of Asafo flags, with a proliferation of workshops and artists passing down the craft through apprentices.

When Ghana became the first sub-Saharan African country to gain independence in 1957, Asafo flags reflected the shift to a new era of sovereignty. The country’s Black Star Flag replaced the Union Jack in the corner of many flags and they continued to be both displayed and incorporated in events. As Gus Casely-Hayford, a curator and cultural historian, said in a video for HENI Talks, “It’s a different kind of relationship to material culture and to history that you show respect through using things rather than by trying to hold them in aspect.”

By the 1990s, Asafo flags caught the eyes of art collectors around the world, with art exhibitions and the book Asafo!: African Flags of the Fante, released in 1992. But as they became souvenirs and memorabilia, the creativity and quality dwindled in some cases, with fake flags proving an issue. But even today, a number of Asafo flag artists are still creating new designs and trying to encourage a new generation of Ghanaians to learn their cultural heritage.

Baba Issaka began making flags as a child, learning from his father, and now has a workshop in the town of Agona Swedru. Issaka takes around three weeks to create a flag for festivals. He said in an interview that this profession is based on skill and patience, which don’t always mesh with the fast-paced modern society. Patrick Tagoe-Turkson is a multimedia artist who paints, sculpts and performs, as well as creates Asafo flags. Tagoe-Turkson was taught how to stitch flags by community elders. He works to make sure the art doesn’t die because “the flags are a record of our history. They tell stories of our lives.” Using all types of fabric he finds in the market, he said that any objects can become a flag if it succeeds in imparting a message: “We believe that the flags are spiritual elements. They are spiritual objects. So things that are meant for the spirit are to be done by hand.”

The art collective, Wandering People, sells a selection of vintage Asafo flags here.