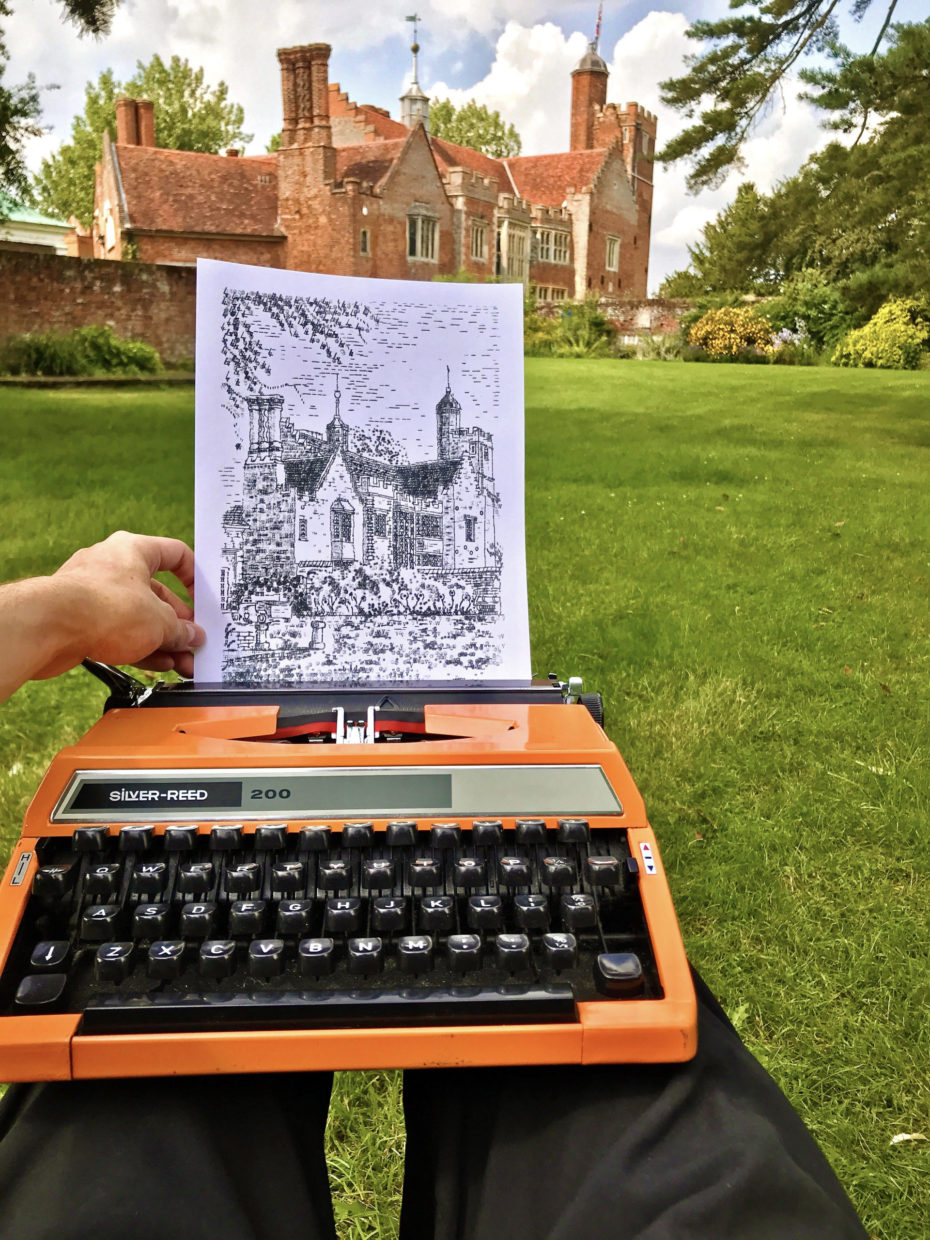

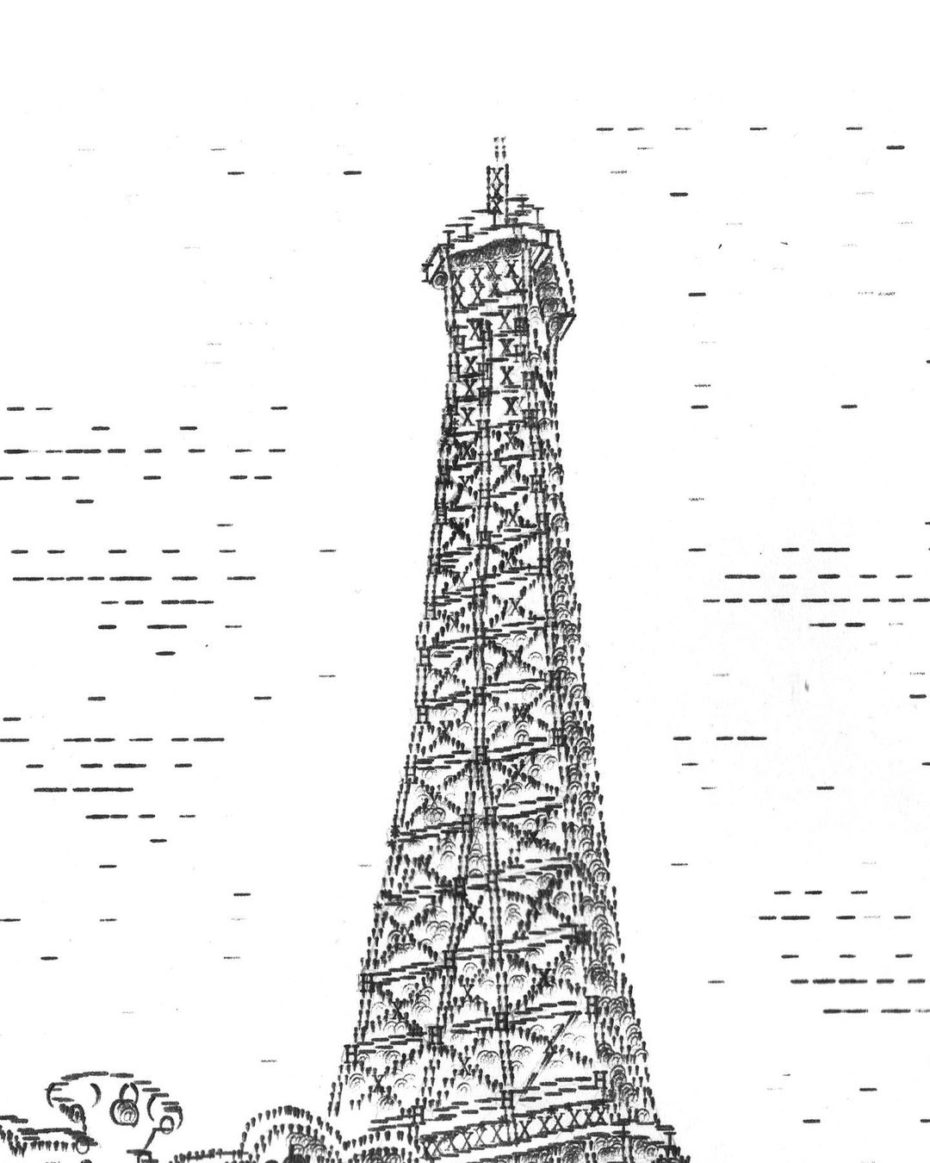

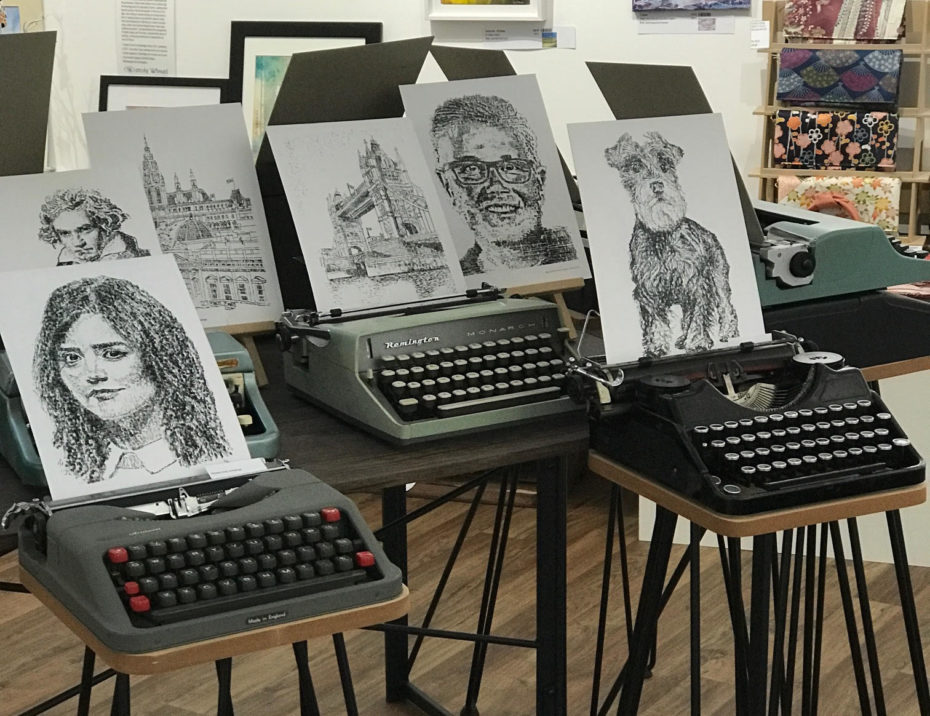

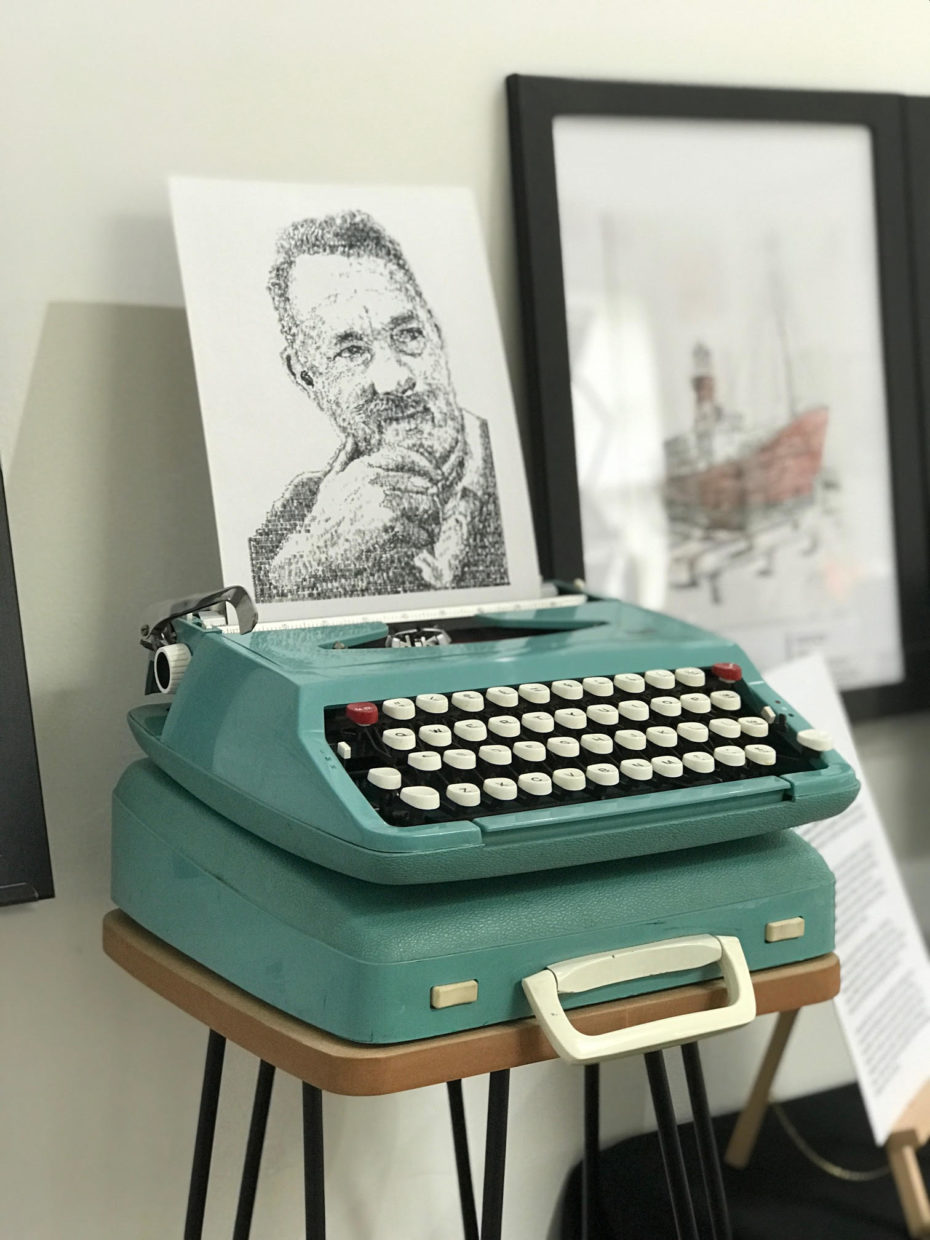

Famous celebrities, historic English buildings and city skylines: What connects all of James Cook’s art pieces is they are made with an unexpected tool, an old or unwanted typewriter. From Essex, Cook first learned about typewriter art while researching Paul Smith, an American artist with cerebral palsy who honed the craft over 70 years. Cook has now created over 100 typewriter art pieces, and amassed a collection of over 30 typewriters. He accepts commissions – and typewriter donations – from around the world, bringing life back to a seemingly antiquated technology. Messy Nessy chatted with Cook about the intricacies of “typicition,” what inspires him and the celebrity he would like to bond over typewriters with.

How has your relationship to typewriters evolved or changed since you started make art with them?

I’ve done typewriter art for about seven years, on and off. Recently, it has become more of a full-time job. I still use the same typewriter I started with for the majority of my drawings, a 1953 Oliver Courier. (Courier refers to the font type.) I’ve done over 100 pictures and more than 50% of them have been done on that typewriter. I’ve honed my skills using that one and how that reacts to my movements and how I react to its movements. It sounds strange, but typewriters have their own unique character, characteristics to how they work: They’re different shapes, sizes, ages. The one I use for portraits is good at subtle movements. Originally, it would’ve been an expensive typewriter because mechanically, it’s precise and therefore is good at finite details, like typing in someone’s eye. There’s an Olympia SG3, an A3 typewriter. They’re quite rare because most of them take smaller, A4 document paper. That’s good for the big portraits because otherwise you’re having to stitch paper together at the end, which is always tricky. I’ve got four typewriters that are the workhorses that I go to for the majority of the drawings. But I’m moving to new typewriters because of what I’m doing with them; they don’t like being abused the way that I do because you’re working against what it wants to do: It wants to do just do left to right. So they have a tendency to break. The collection is handy because there’s always a spare in the worst case scenario.

How did you develop your artistic technique?

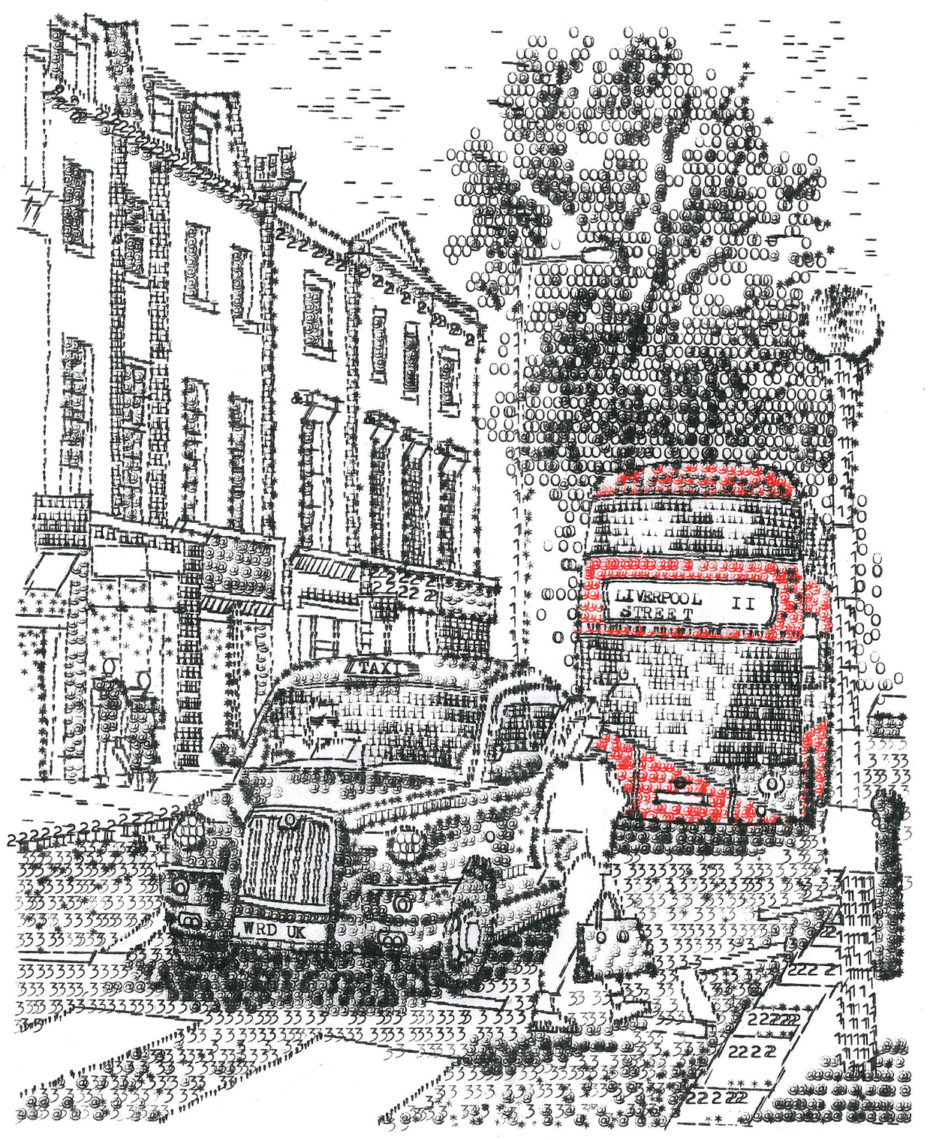

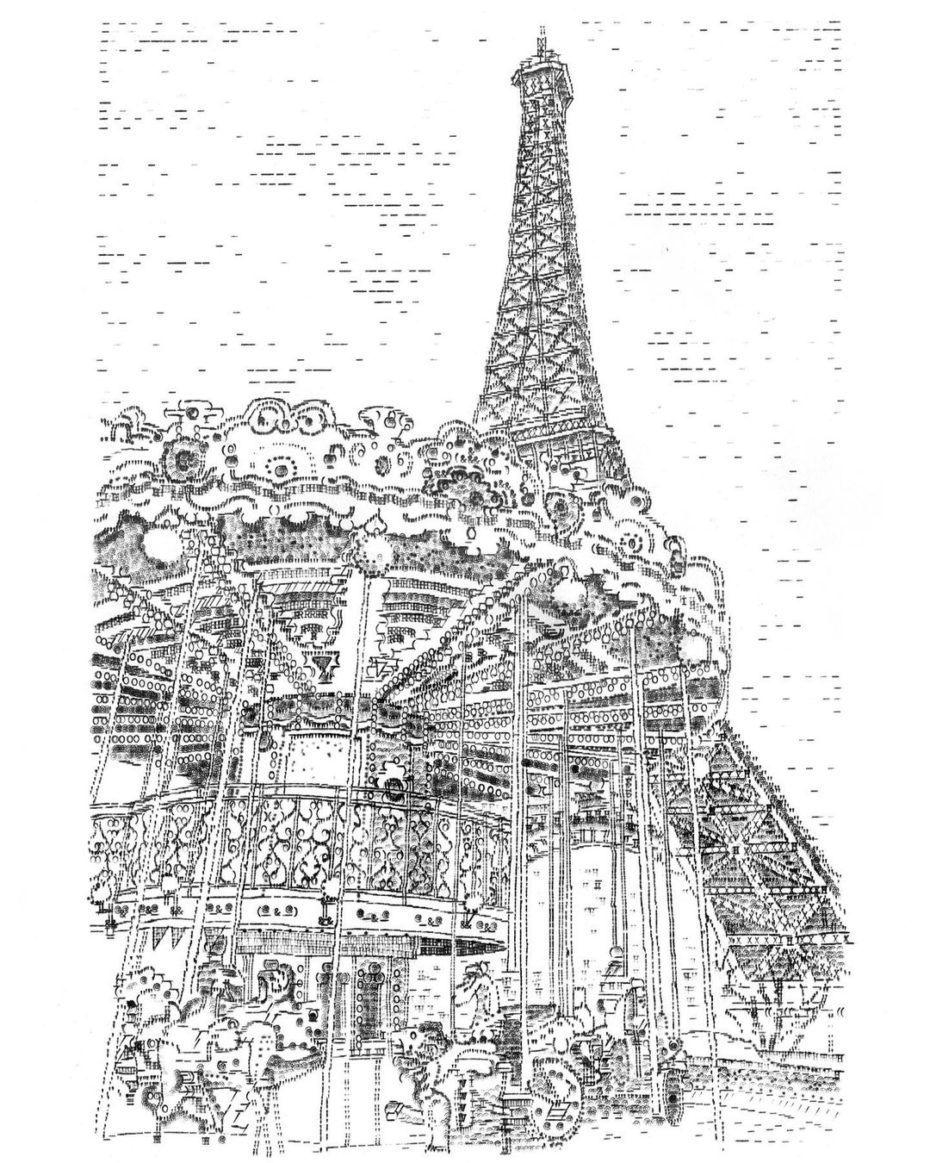

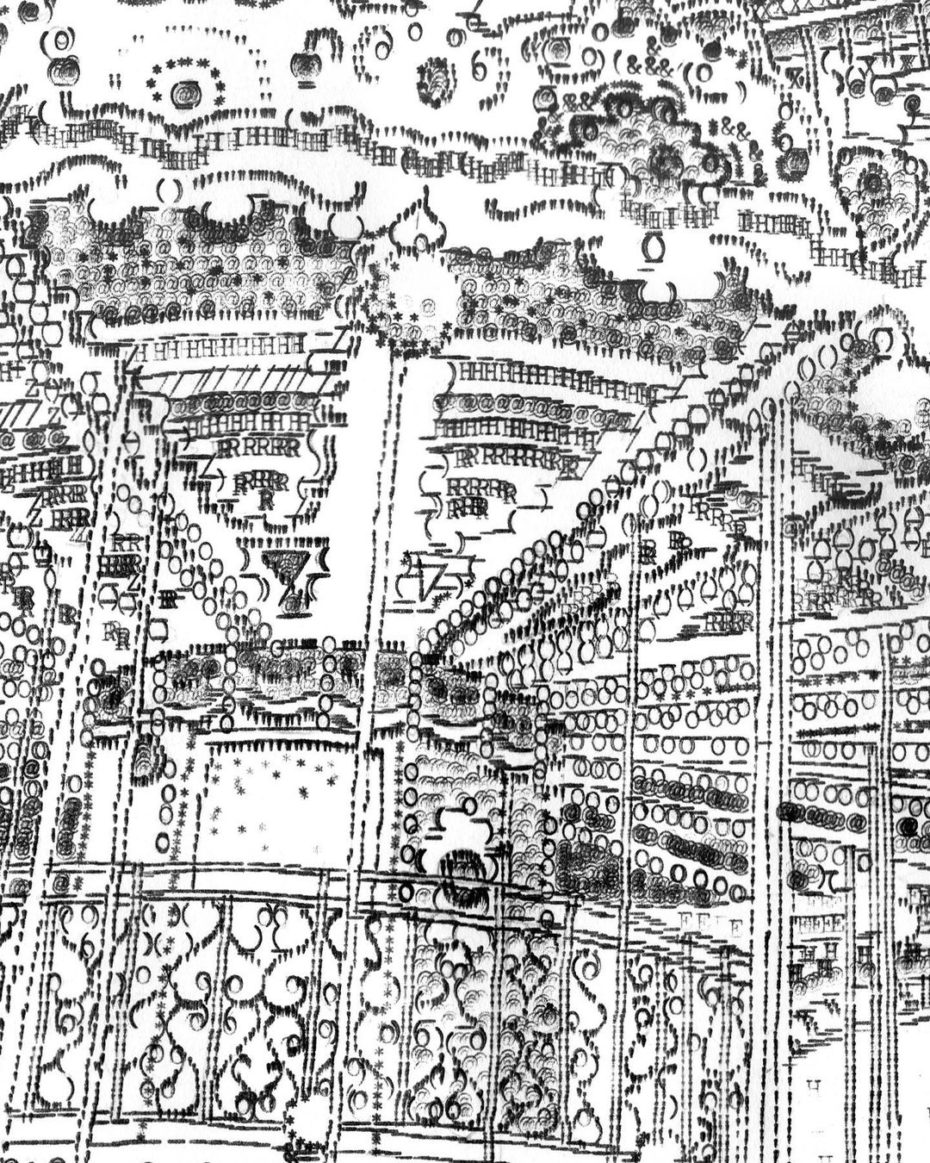

I suppose the technique develops around the first typewriter and the keys that weren’t broken, the ones that actually you could press down and something would happen. You’ve got 40 keys on a typewriter; it’s about using those shapes and the punctuation, letters, numbers and how you overlay that to create what’s in front of you. I use the bracket symbols to do people’s eyes and an “0” in the middle so you leave the whites of someone’s eye and that’s the reflective part. Brick work is — depending on the scale — in underscores and then “I”s to do the gaps in between the bricks. Roof pitches are forward slashes if they’re going left to right, and you make the compromise going the other way because none of the have a backslash; it wasn’t invented when most of them came out. I use “L” as a compromise between a backslash. Some of those techniques are being inspired by Paul Smith, seeing his collection as reference material. There’s a prescribed set of keys I always go to now. There’s normally a subject that’s similar to what I’ve done previously. The thing is you can add, but you can never subtract. Once you’ve stamped that ink into paper, that’s it. You could use Tipp-ex, but I don’t.

With typewriters, there’s no erasing a dodgy brush stroke. So how does that influence your art?

It’s like writing at school: In English class you’d write in your book and you can’t erase what you’ve written. It’s easy in Microsoft Word to be so pedantic and look at a blank screen. With typewriters, there’s more permanent to what you put on paper. Sometimes that leads to more creative outcomes because you can’t delete what you’ve put on the page. The whole process of making the art in itself, you have to think.

Drawing with a typewriter is one of the only ways of making art where you use both hands: You’re typing and you’re moving the cartridge at the same time. If you’re on location, you’re looking at what’s in front of you. I hope that if typewriters make a resurgence, it’s because it’s an analog way of creating something — be it a written piece or drawing. There’s more of a craft to writing because the actual stamping of the keys is your own fingers physically pressing to make those words.

How do you acquire new typewriters?

Literally, typewriters come in the post, just turn up on my doorstep. They’ll leave a message that says, like, “This was sitting in the back of my cupboard for the past 20, 30 years. It’s collecting dust. We don’t want it anymore. You might as well do something with it. And if you do, let us know. We’d like to see the results.” I send a print to say thanks. I’m always on the lookout for new typewriters. Someone recently sent me a typewriter used in litigation. It has law punctuation. The customer is a lawyer. He wants a drawing made up of specific punctuation relating to his job. One of the typewriters was given to me by a man whose father was a BBC journalist. It has Arabic texts, which you don’t see commonly. One woman, her role was lady in waiting for the Queen. She typed corresponding letters to people that turned 100. She said, “Well, I’ve got this typewriter from when I retired in the ’80s and you might as well have it because I’m not using it.” She can’t sell it because no one wants it.

That’s interesting how the typewriter is not only the tool, but becomes part of the art itself.

I’ve tried to do it more recently, weaving in the value of using the language, rather than just the typewriter being a device where I’m using the shapes to represent what the subject is in front of me. One example is last year, a customer in China contacted me because his mother had recently passed away. He wanted a large format picture based on a photograph he dearly cherished. When they were clearing out her house, they found the wedding speech she read on his wedding day. He wanted this a portrait, but when you look closely, you have little segments from the wedding speech written in. It’s always a challenge because obviously, you’re trying to create a picture. You have to be careful with not making it too obvious and try to conceal those messages into the work.

How have you been inspired during the pandemic?

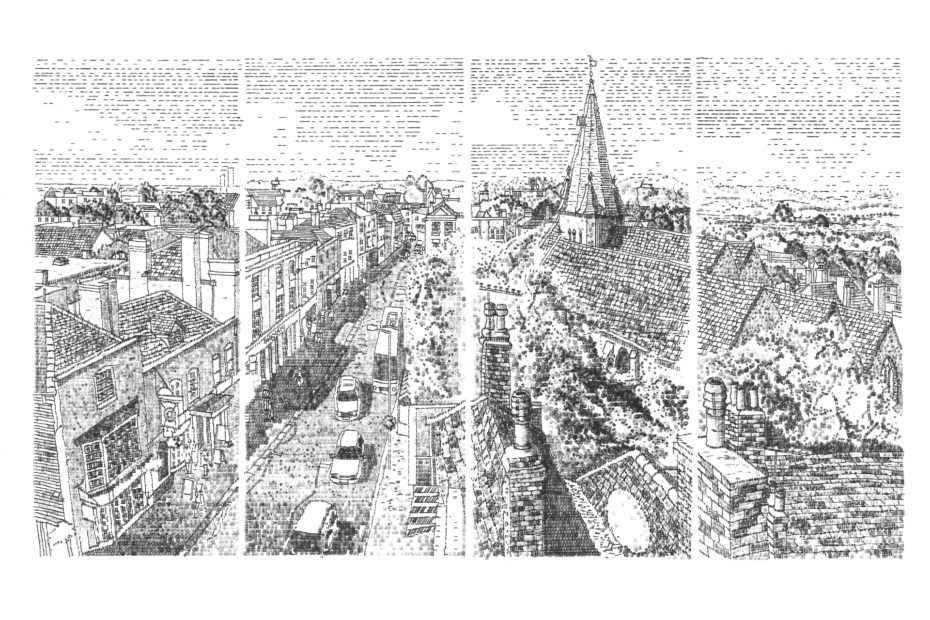

I was living in London, studying for a master’s degree in architecture. When lockdown happened, I left because our courses went online. The exhibition I’ve just done was based around my time in lockdown and appreciating what’s available on your doorstep, which for me, because I live 50 miles north of London, in a countryside area. There are hidden gems, like old historical landmarks, tucked away behind parks and forests. That was the theme: the idea being that most people’s daily exercise was going out running and mine was going out and drawing.

How do you see your art as preserving these machines?

I suppose it brings an awareness back to them. Tom Hanks still writes screenplays or scripts with his collection. A lot of people comment on my work, saying, “You should send some drawings to Tom Hanks or do a portrait of him.” I’d love to see his collection of typewriters; mine are just a little bit worn around the corners and a bit raggedy. But besides that, I suppose typewriters have become a piece of furniture, so some people think it’s cool to have them on display in the house.

It’s funny because you probably didn’t even grow up learning to use them.

Most people in my generation wouldn’t know how to use them. I’m 24; I never learned to write with a typewriter. You go on Facebook Marketplace, people are selling them for 10, 15 pounds. They can’t get rid of them because it’s like cassette tapes: It’s an obsolete piece of technology. When I work on different typewriters, it’s surprising how they’re so different to the next one. I hope they do a U-turn and do what vinyl records in the music industry did where they get used again. There’s a small but growing number of people doing typewriter art now. There’s a lot more compared to when I started. They each approach it in their own unique way: You’re limited by what’s in front of you, but the results are limitless.

What’s your dream location to bring a typewriter?

There’s more than 100 on my list. I’d love to go to Mulholland Drive; there’s the Chemosphere, this UFO shaped building. It was built in the ’60s into the cliffside. I’d love to visit Frank Lloyd Wright houses or Manhattan and do a rooftop skyline drawing, like at the Woolworth Building, which has lower roof terraces looking out to Lower Manhattan. There’s also some places in the UK, like the rooftop of Victoria Tower looking toward Parliament.

How can people reach out to you?

You can email me at jamescookartwork@gmail.com I’m always on the lookout for new locations to type. If anyone has suggestions — they know someone who has access to a balcony with this incredible view and they’re more than happy for me to do a drawing — in return, I’ll give them a full-size print framed.