“Are you sure you want to get off here?,” asks the train conductor, and with good reason: for it is nighttime at Amtrak’s least used railway station. Indeed, Thurmond, West Virginia is so remote and rarely used, that it is a request stop on America’s nation rail network: not only do you have to ask the train to stop for you to get off, but coming back the other way, you have to stand by the tracks to flag the train down and hope you get picked up again, affording you the somewhat thrilling experience of hitchhiking by train. And the reason hardly anyone uses the small station is that Thurmond, West Virginia is a ghost town.

Amtrak’s Cardinal service is a sleek, silver train that runs between New York and Chicago three times a week. Running south and west through the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains, the train rolls through the Shenandoah Valley on a journey that takes just over a day. About halfway along the route lies the deserted town of Thurmond. As the train pulls out of the station, leaving me on the empty platform, the other passengers relaxing in their sleeper cabins, or being seated in the dining car, are perhaps wondering what the train is doing in a town where few lights are on; empty and silent, save for the distant sound of the wild white water rivers of West Virginia.

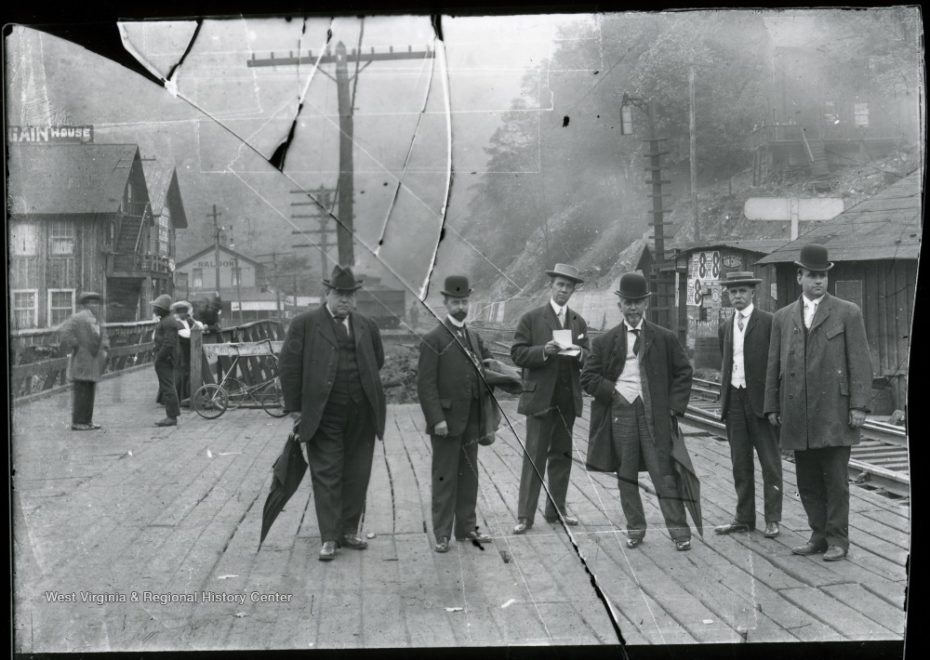

A century ago, the scene at Thurmond couldn’t have been more different. In the early 1900s, the banks of the New River Gorge National River were some of the richest in the State of Virginia, with twenty six coal mines surrounding the town of Thurmond. A classic boom town, Thurmond became the jewel in the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway’s crown, with more coal and wealth passing through the small town than even the big cities of Cincinnati and Richmond combined.

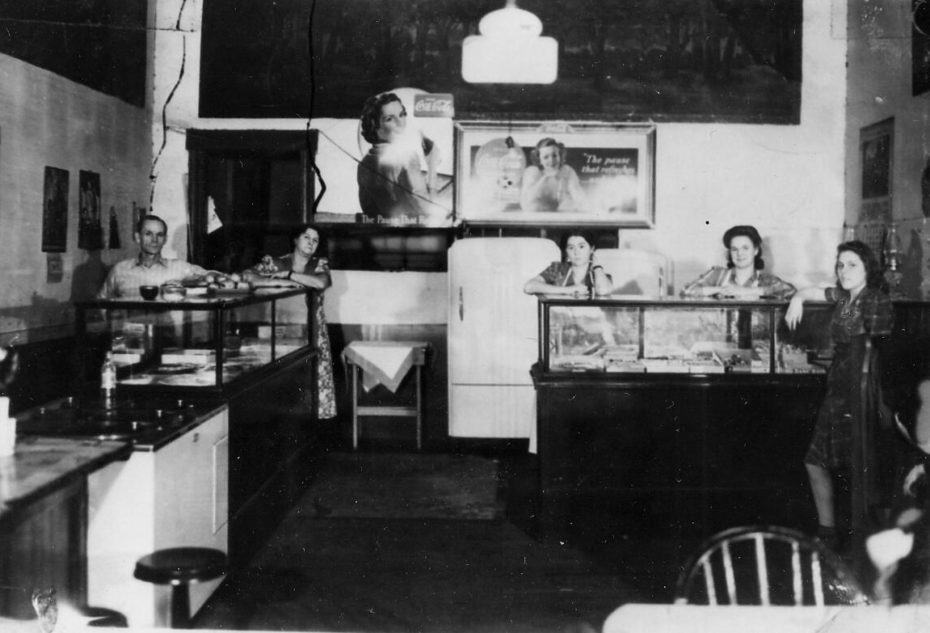

Hotels, boarding houses, saloons and stores thrived, catering to rich coal barons, miners and pleasure seekers alike. At its peak, fifteen passenger trains a day stopped at Thurmond, but like so many other boom towns, once the coal mining stopped, Thurmond was all but abandoned. Perhaps the rise and sad decline of the town can be best highlighted by looking at the station itself: in 1910, Thurmond welcomed over 75,000 passengers. Last year, just over two hundred people disembarked at the empty station, one of whom was me.

Technically, Thurmond isn’t totally a ghost town, as the population currently stands at just five. By peculiar co-incidence, it turns out that one of the five is a cousin to a work colleague of mine, who kindly afforded me the rare opportunity to spend a weekend in the otherwise empty town. Tighe Bullock is a 32 year-old developer of historic buildings and an attorney. “I was one of the last children born to the ghost town of Thurmond, West Virginia,” he explains. “When I was born here, there were around 80 folks still in the town. We had a hotel, a restaurant, and a close knit community. Now just five people live in the town.”

One of the first things you notice about downtown Thurmond is that there’s no pavement. Instead of a sidewalk, the ribbons of steel of the railway track drop you right outside the front doors of the brick buildings that made up ‘Commercial Row’. In fact, until a bridge across the New River Gorge was built in 1921, the only way in and out of Thurmond was by train. Once Thurmond had two hotels, two banks, restaurants, clothing stores, a jewellery store, a movie theatre, several dry-good stores, and an office of the Baldwin-Felts Detective agency.

But today all that sadly remains of downtown is a row of three old brick buildings: the abandoned Mankin Drug Company building, the New River Banking Trust Company, and a solitary closed branch of the National Bank of Thurmond, built with limestone columns, marble floors and gold plate glass window advertising “Any Amount Starts an Account – 3% interest on savings”, a remnant of more prosperous times when the bank’s safe was filled with gold and money from the mines.

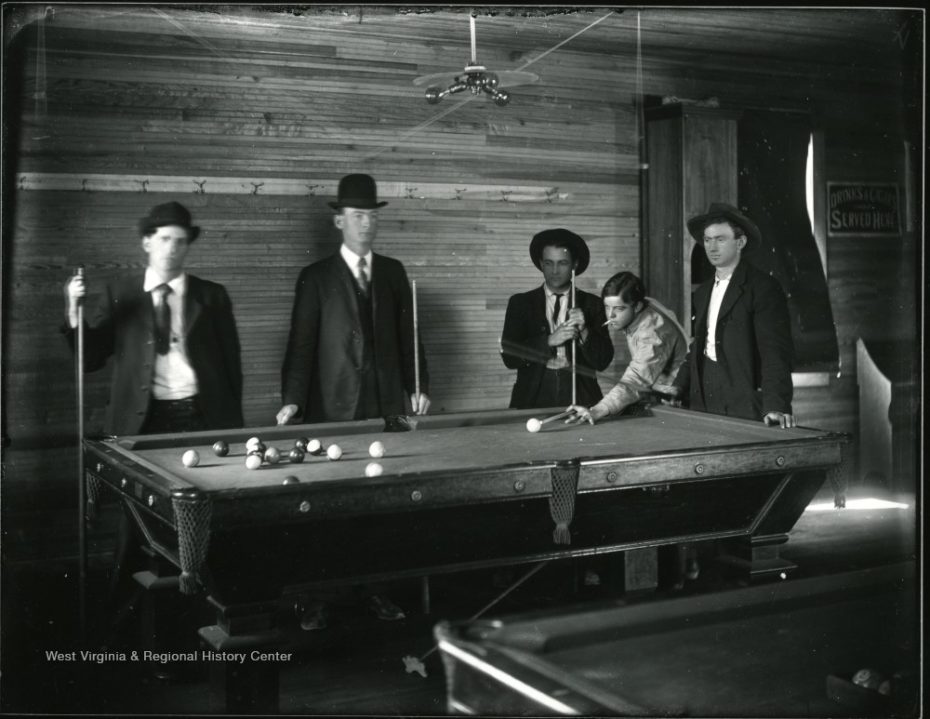

Thurmond was named for a Confederate Army Captain, W.D. Thurmond, who was given seventy three acres by the river in payment for surveying work in 1873. Neatly positioned at a sharp bend in the New River Gorge, Captain Thurmond had lofty ideals for his settlement, banning alcohol in the town which was officially incorporated in 1903. But the rough and harsh work of mountain coal mining and railroading swiftly saw Thurmond develop a notorious reputation as a raucous settlement. “It was busier than Broadway on a Saturday night,” said one store owner, Herman Monk, as Thurmond became a town of gambling tables, prostitutes and saloons such as the Bear Wallow and the Black Hawk, leading the Fayetteville Journal to start calling Thurmond, the “Dodge City of the East”.

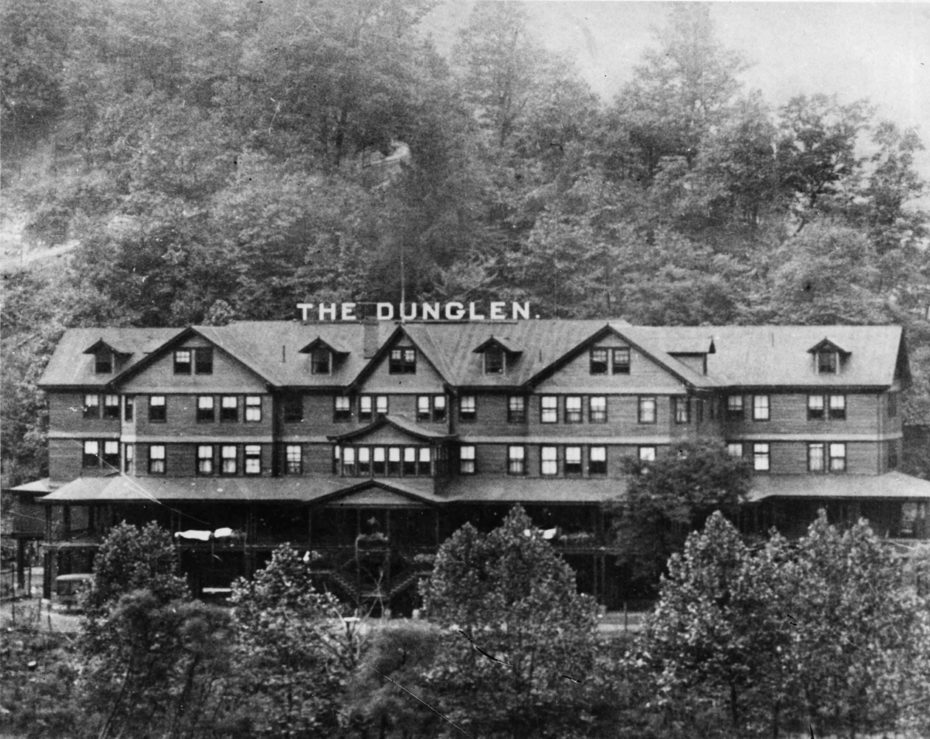

The chief pleasure resort of Thurmond was found on the opposite river bank at the upscale Dunglen Hotel. Three stories high with a double decked porch overlooking the river, the Dunglen’s one hundred rooms were seldom empty at $2.50 night. Ragtime jazz bands played long into the early hours, diners enjoyed fresh seafood on fine bone china, whilst what one newspaper described as “ungood girls” plied their trade upstairs, and gambling was offered in the basement.

Perhaps the only hotel in America that had its own working mortuary on the premises, the Dunglen Hotel can still be found today in Ripley’s “Believe It Or Not”, for hosting the world’s longest running poker game that ran for an incredible fourteen years. No wonder the Dunglen became known as “Little Monte Carlo of the Coal Fields”

But within just a few decades, Thurmond would be all but abandoned. As the coal seams along the riverbank tapped out, the mines moved further away. But the real death knell for Thurmond came from the decline in the industry which had long supported the town: the railway.

Thurmond had thrived as a steam train town, its rail yards, water towers and coal supplies working twenty fours a day to service the principal stop on the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway. But the switch from steam to diesel engines meant there was no longer a reason to stop at Thurmond to take on water and coal. Once the trains stopped, the small town with railway tracks for its Main Street, emptied out.

“Thurmond is a microcosm of the boom and bust cycles of natural resource extraction, and should be a tale of caution for other cities and states that refuse to diversify their economies,” explains Tighe Bullock. “The people of Thurmond did everything they were told to do as good Americans. Buy your home. Pay it off. Supplement your diet and budget with vegetable gardens. Be frugal. Work hard, provide energy for the country, and the country will take care of you. But as the coal seams were mined out, the mine entrances moved further and further away. It became harder and harder to find work in the area, and so people moved, following the mine entrances and jobs.”

As people drifted away from Thurmond, the Bullock family were one of the few to stay. “My father worked in the coal mines, my mother was an educator,” explains Tighe. “The Bullocks had been tobacco farmers since the first Bullock leapt ashore at Jamestown around 1615. My father moved to West Virginia as a geologist because he believed energy was the future of our country, and he wanted to be a part of it. So he moved to Thurmond to be close to the mines he worked in.”

As the town’s population dropped into the double digits by the 1970s, the Bullock family’s role in civic duty grew; at one point, one of the quirks of living in a tiny town saw Tighe’s parents actually run against each other for Mayor. “Both my parents served as Mayors at different points,” explains Tighe. “My mother mostly stayed home to take care of my sister and I, and ended up doing most of the Mayoral work while my father worked in the mines. Not satisfied with doing the lion’s share of the work, my mother decided to run against my father in the next election. My father received one vote, and he voted for himself, as the story goes. The town had a good laugh about it, and the title of the article in the local paper read ‘Bullock Defeats Bullock.’ ”

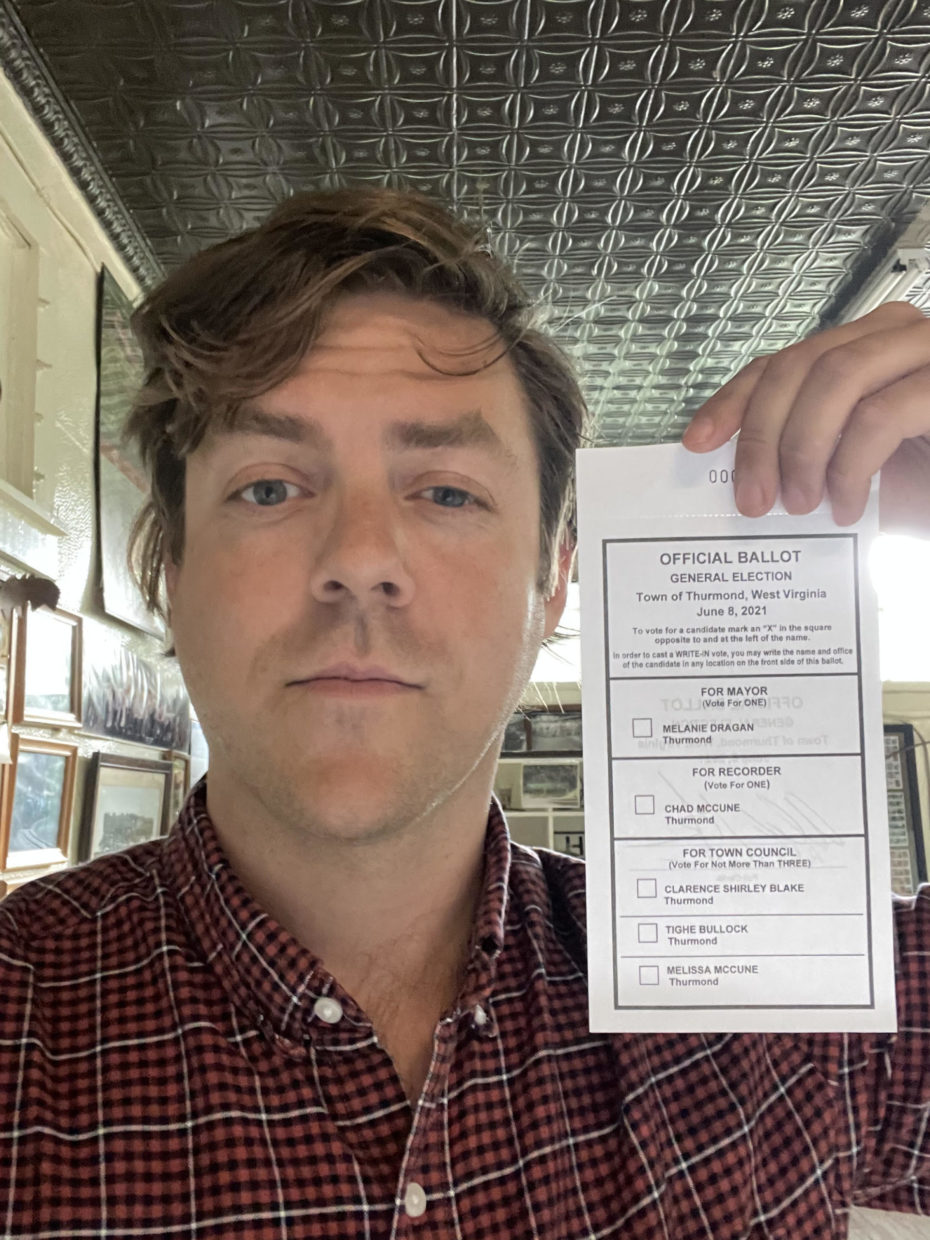

Tighe Bullock himself is a long standing Councilman in the town with population now recorded at five.

“Growing up in Thurmond and watching the town dilapidate made a lasting, deep impression on me. I didn’t understand what market forces had occurred to allow this to happen, but I knew I wanted to do something with my life that would halt and reverse these forces, whether in Thurmond or elsewhere in the State.” One of the advantages in governing a ghost town is that it’s easier to make important changes. In 2015, following an unanimous vote by all five residents, Thurmond became the smallest town in America with a ban on employment, housing and public accommodation discrimination against LGBT individuals. “The big message was just, from the smallest town to the biggest town, West Virginians believe in equality,” Tighe told the Washington Post.

Walking around Thurmond today is a saddening reminder of the countless other boom towns throughout America, which once thrived with human activity but today are silent and forgotten. Many buildings have long since disappeared, either torn down or as in the case of the famed Dunglen Hotel, burnt to the ground in suspicious circumstances. Many of the family homes lie in increasingly dilapidated condition, whilst some have disappeared altogether, leaving only behind a white picket fence and patches of perennial flowers which still blossom untended each year in the shape of once loved front gardens.

Much of Thurmond was taken over by the National Park Service in 1995, which embarked on a programme of stabilisation and upkeep of the Amtrak station, which is still used once every three days. “The Park Service bought much of the town up in the 70s and 80s,” explains Tighe, “waving more money in the faces of the town folk than they had dreamed they would ever see. It was a pittance. Robert C. Byrd, our controversial, long time Senator, pork barrelled money to buy up the town, but not enough to actually do anything with the houses. They continue to rot to this day.”

One aspect of Thurmond which still draws visitors is white water rafting. The New River Gorge showcases geology and a natural beauty stemming from one of America’s oldest rivers, and became part of the National Park System in 1978. The white water rafting business is largely overseen by the other prominent family left in town, the Dragans. “My family and another, the Dragans, remained,” explains Bullock. “The Dragans are a very interesting, entrepreneurial family, credited with bringing New River white water to the mainstream public, forever changing the image of the Gorge in the American psyche.” Tighe’s parents actually met on a rafting trip, his mother eventually leaving America’s biggest metropolis, New York City, for one of its smallest.

The town is fortunate to have Tighe Bullock, a passionate restorer of historic buildings, as a resident. “It was too late for Thurmond, but not for other areas of West Virginia,” he says. “And so I have dedicated my life to reversing the downward trend of stagnation and dilapidation in the Mountain State, and I credit Thurmond as my muse in this endeavour. However, with the recent designation of the New River as America’s newest National Park, perhaps the town has another chance to remake itself. The question will be, is it sustainable this time?”

Between 1910 and 1950, a staggering three million people once stopped at Thurmond Depot Station; the trains were used by coal miners, rail yard workers, traveling salesman, children journeying to school, and pleasure seekers from the neighbouring coal towns.

As I wait by the side of the track, arm outstretched to hopefully flag down the thundering New York bound express train that won’t pass by again for another three days, its hard not to be struck by the surrounding empty buildings, sad reminders of the town’s historic and vibrant past. “Thurmond, to me, is a place of reflection, contemplation, and simple existence,” says Tighe Bullock, perhaps explaining why he’s just one of the five people who still live here. “There is no pace – the town simply is. I have many great memories here of my family and friends that I will always carry with me. Some find the silence eerie. I find it peaceful. It is home.”