In the once harsh and bug-infested swamplands of southwest Florida, lies the remains of a strange 19th century settlement. Founded by a charismatic leader who led his members into the quagmire to build a “New Jerusalem” and seek immortality through celibacy, the commune revolved around the belief not that the earth was flat, but hollow – and that we humans were living inside its core. Today, a state park is dedicated to what is left of the preserved remains of the utopian colony. Frozen in time, it’s one of the few actual standing ghost towns in Florida. Welcome to the Koreshan Unity…

It all started with science. Well, ostensibly. Cyrus Teed, an eccentric medical doctor and alchemist from Utica, New York, often experimented with dangerous levels of electric current. During one late night in his laboratory in 1869, Teed was knocked unconscious by his own experimental attempt to turn lead into gold and had a vision –or as he called it, “The Illumination”. A beautiful woman appeared and imparted to Teed the truths of the universe: the secret of immortality, that God was both male and female, and that we live on the inside of the Earth’s crust. The angel told him he was the seventh prophet in a line that included Adam and, most recently, Jesus and that he had been sent to redeem humanity.

The 1800s and early 1900s saw a rash of celestial beings apparently visiting middle-class white men in America, anointing them as prophets and exhorting them to found new religions. As the ripples from the Industrial Revolution continued to wash across all levels of society, some found themselves wanting better answers and a different way of life, and charismatic leaders – often with supposed divine calling – were there to fill the gaps. A number of these fervent religious groups and nascent utopias began in western and central New York state, an area that came to be called the burned-over district in reference to the fire-and-brimstone, revival-style evangelism that seemed to set the region aflame. Teed would certainly have been familiar with some of his regional forebears and contemporaries: Joseph Smith and the Mormons; the Shakers; the Millerites; and the Oneida Community.

But by the time Teed began recruiting followers in the 1870s, New Yorkers in the burned-over district were already feeling rather burnt out by these new-age religious movements. His eccentric beliefs damaged his medical practice, and his repeated attempts to start a communal settlement in New York failed. So did his marriage. He left his wife and young son, moving to Chicago in his pursuit of the New Jerusalem he believed he was destined to found.

Teed called his new religion Koreshanity and changed his name to Koresh, the biblical version of the name Cyrus, referencing the Persian king who conquered Babylon, freed the Jews and led them back to Jerusalem. If the name Koresh rings a bell, you may remember David Koresh and the Branch Davidians, a different religious sect that ended in flames and tragedy during a standoff with federal law enforcement in 1993 in Waco, Texas. While both Cyrus Teed and David Koresh adopted the name to solidify their own power over their followers, the Koreshans and the Branch Davidians are unrelated.

Chicago proved a more fertile recruiting ground for Koreshanity, and soon Teed amassed more than a hundred followers hoping to build a communal society out of the organization he dubbed The College of Life. The Koreshans were hardly rubes. Most were middle and upper-middle class and highly educated, and 75 percent were women. Koreshanity’s tenet of equality between the sexes clearly appealed in an era when women still did not have the right to vote in the United States nor the same rights as men to property and self determination. Quite a few female Koreshans joined the movement without their husbands, and Teed was sued by more than one angry husband for alienation of their spouses. In one death threat, the anonymous letter writer said:

Teed

You will be shot and killed by me on sight, I am determined to rid this community of you, you dirty black leg s____ of a b_____ you will be shot the first time you show you face in a certain section of this city

A friend of woman

(The redactions are original to the letter.)

Jilted husbands weren’t Teed’s only detractors in Chicago, and soon the Koreshans were on the hunt for land where they would be free to create their New Jerusalem, which Teed envisioned as a city of 10 million people. In 1894 the group landed in the swamps of southwestern Florida, buying 300 acres of cheap land in unincorporated Estero. The area was sparsely populated by people but densely populated by snakes, mosquitos and palmettos, and the Koreshans spent years hacking out a pioneer existence, living in tents and surviving on peanuts.

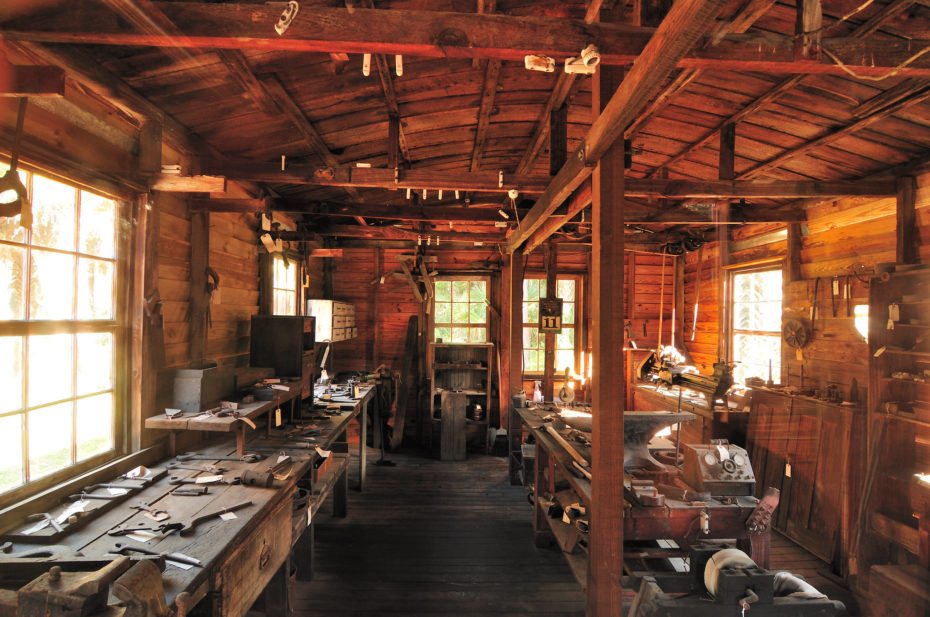

But after a few years of hard work in the Florida heat and humidity, the Koreshans managed to raise a vibrant and thriving community from the banks of the Estero River. The Koreshan Unity, as the settlement was called, included a publishing house, a general store, a sawmill, cement works, a plant nursery, machine shops and a thriving bakery that produced 600 loaves a day.

This success was due in part to the group’s philosophy of communal living. Members were required to sign over all material property to the Unity upon joining. As members, each person “worked unto their abilities and received unto their needs.” And while today that might sound a lot like Marxism, the Koreshans saw it as a harkening back to the ways of the early Christians. The community never reached Teed’s projected 10 million; at its height the Koreshan Unity boasted around 200 members.

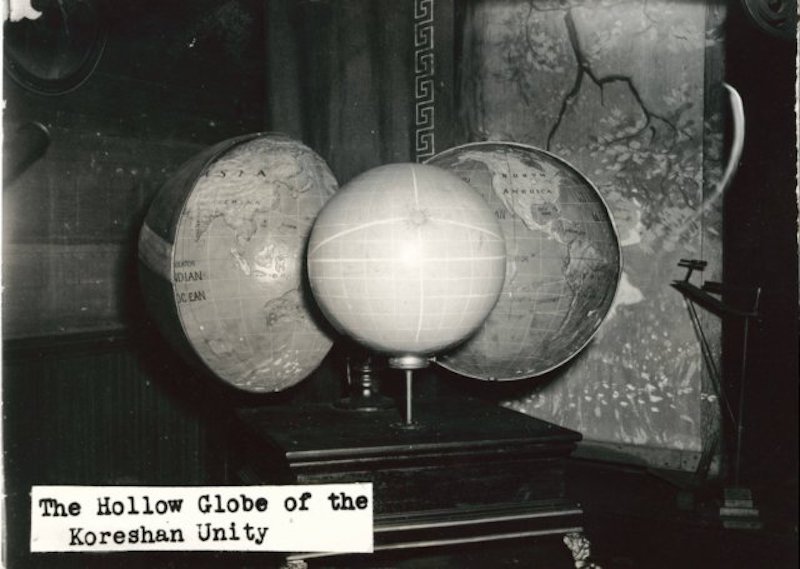

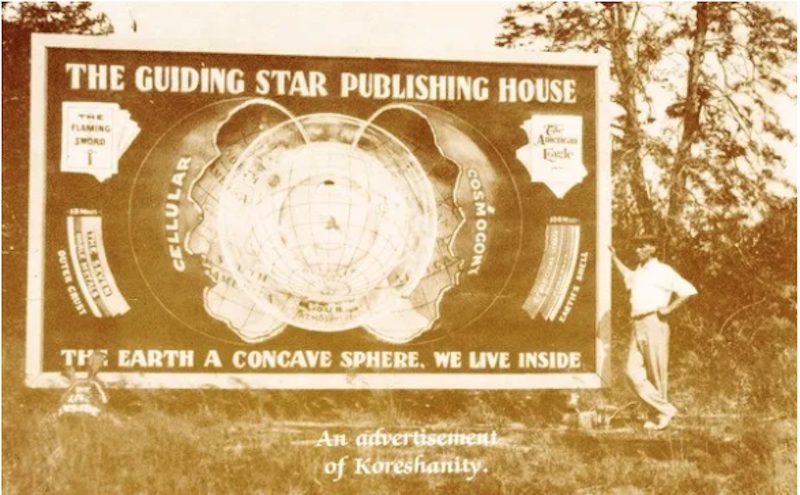

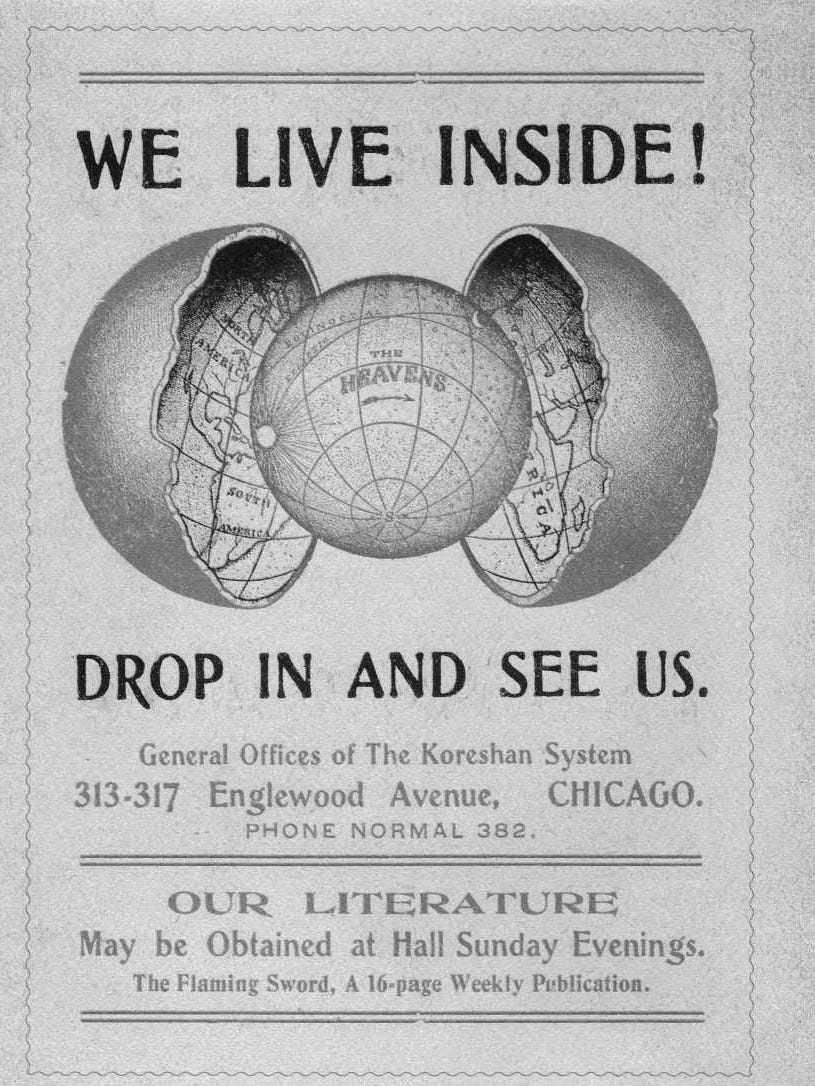

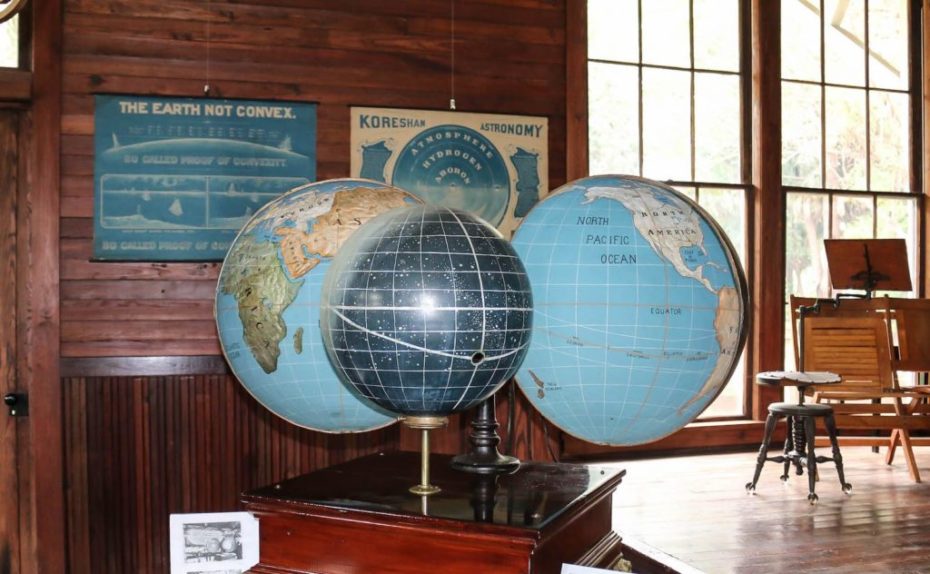

The Unity’s general affairs were managed by seven women referred to as the Planetary Sisters, each corresponding to one of the known planets at the time. Teed represented the sun. Naturally. And Teed’s chosen successor, a woman named Annie Ordway who Teed renamed Victoria Gratia, was the embodiment of the moon. While the Planetary Sisters operated independently within the Unity, they were all required to have male counterparts when dealing with the general public who did not readily accept the radical equality Koreshan women were afforded. While much of the social organization within the Unity sounds progressive and modern today, not all their beliefs translate as easily. Teed developed the theory of cellular cosmogony, stating that the earth is a concave cell with the entire universe contained inside – a bit like the Tootsie Roll center of a Tootsie Pop. Teed dismissed the idea of gravity and believed it was the heavens in the center of the sphere that rotated while the Earth remained still. The Koreshans even developed experiments to “prove” the Earth was concave using an elaborate tool they invented. They adopted the tagline “We live inside!” and printed it on signs, pamphlets and fliers in a rather ineffective attempt to interest others in their belief system.

As with every community in which the Koreshans settled, the locals viewed them with hesitancy and suspicion due to their unorthodox religious beliefs. But the surrounding community benefited from the Koreshans’ industry and interest in culture, so they coexisted more or less peacefully, for a time.

There was a tri-level system of membership which included an outer level of non-believers who were willing to wok for the unity. This group was called the Patrons of Equation, and allowed for marriage and participation in the secular aspects of the unity. Thomas Edison, who wintered in nearby Fort Myers, often attended events at the Unity and found an eager audience for his own ideas about the domestic use of electricity. Edison traded plants and seeds with the Unity and gifted them with bamboo cuttings, the offspring of which still fill the Unity grounds today. Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone were also regulars at Koreshan cultural events. The Unity organized southwest Florida’s first symphony orchestra, performed plays, from Shakespeare to original works, and regularly held concerts and celebrated festivals.

They founded a school to educate their own children alongside those of the locals. Teed offered medical care. They sold the fruits of their agricultural labor and fishing industry to the locals and even built their own power plant which supplied electricity to the surrounding area.

The inner core of the group, called The Pre-Eminent Unity, did not allow marriage and practiced celibacy. The Koreshans believed that the key to immortality was celibacy. “You would focus all your sexual energies on his [Teed’s] mind and then when he died, you would disintegrate and come back as neither male nor female,” explains Koreshan State Park museum curator Robert Hughes. A middle group however, allowed for marriage, but sexual relationships were only to be for the purpose of reproduction.

Unlike some of history’s more dangerous religious cults or sects, members were free to leave and weren’t shunned if they made the call to do so. Koreshans could also visit their family members that lived outside the settlement.

The trouble really began when the Koreshans entered politics. In 1904, Teed decided to incorporate the town of Estero. While those living nearest the Unity seemed largely unconcerned about this development, it caused considerable anxiety among established politicians in the county seat of Fort Myers. Nothing creates enemies faster than money, and when the local politicians realized Teed’s plans could affect their own tax revenue, any resolve to peacefully coexist with the outsiders vanished. Teed and his followers did little to help smooth the situation over, as he rather enjoyed being in your face and controversial. Pushing the agenda of women’s suffrage, the Koreshans formed their own political party, the Progressive Liberty Party, which only ramped up the rhetoric. In 1906, while in Fort Myers on business, Teed and some of the Koreshans got into a brawl with some locals, including the town marshall. Teed was beaten so severely that he never fully recovered. He died a few days before Christmas of 1908.

Fervently believing in Teed’s immortality and resurrection, the Koreshans placed him in a bathtub on the stage in the Art Hall and waited. Unity children were brought in to view the body, which had already begun to decompose. This was explained away as evidence of the new life beginning to take hold. After nearly a week, the county health officer forced the Koreshans to bury Teed’s body. Members kept a 24-hour vigil at his tomb and moored a boat nearby for when he eventually returned. But Teed’s mausoleum and body washed out to sea during a hurricane in 1921 with no sign of his resurrection.

With the loss of their leader, the Koreshans floundered. They refused to rally around Victoria Gratia, Teed’s presumed successor, and membership slowly and steadily declined, as celibate communities are wont to do. Though the group dwindled, they continued their economic and cultural activities as best they could. Then, in 1940, the Koreshans gained a short reprieve thanks to Hedwig Michel, a German Jewish woman fleeing Nazi persecution. She poured her energy into reviving the community, and after the war she fought for the reparations she was owed, then signed those funds over to the Unity to keep it afloat in lean times. Michel was often referred to as the last Koreshan, a title she waved off saying, “There is no last. We shall continue.”

Despite Michel’s best efforts, only five members remained in 1961. So Michel and the other Koreshans donated 305 acres and all the Unity buildings to the State of Florida, creating a state park and historic site. Michel died in 1982, marking the end of a century-long search for utopia.

The buildings and homes that remain intact are original, including Cyrus Teed’s house, the the Planetary Court (built circa 1904 as a home for the seven women who managed the Unity), the art hall, the general store, the bakery, generator building, machine shops and several members’ cottages.

It would be all too easy to dismiss the Koreshans as just another kooky cult from a less advanced time, and of course it is true that many of their beliefs about science were demonstrably false even then. Yet their work changed both the literal and cultural landscape of the region at a time when southwestern Florida was still a frontier. And, really, were their misguided hollow-earth theories so different from the pseudo-science that goes viral on TikTok? As we enter another age of worldwide uncertainty and upheaval, and as many people feel left behind by advances that only benefit others, we’re all looking for something. But if you venture off toward your own utopia, maybe just be sure the science is peer reviewed.

Koreshan State Park and its historic settlement is open daily 365 days a year from 8 a.m.until 5 p.m.