This is a different kind of story about Versailles; one that they only dared whisper about in the palace’s gilded halls. It’s the little-known story of a witch hunt that unfolded in secrecy within the French royal court, eclipsed in history by a more famous witch hunt that took place a decade later, thousands of miles away in Salem, Massachusetts. Pulling back the curtain on Versailles’ lavish pomp and ceremony, one might not only find the salacious details of a hedonist world within the Ancien Régime, but an occult one too. For lurking among the aristocracy, a shadowy network of black magic practitioners were purported to have sold poison to thousands of citizens, most notably to multiple courtiers and mistresses within the court of King Louis XIV. Murder, panic and scandal ensued during the Sun King’s reign, and a vast conspiracy unravelled which led to the arrest of 194 people and the execution of 36, including scores of prominent aristocrats, on charges of poisoning and witchcraft. This is the story of the Affair of the Poisons.

As the 1600’s were coming to a close, something strange started to happen in the court of Versailles. Members of the French nobility began mysteriously kicking the bucket with suspicious regularity, giving little warning of their untimely demise. Whilst the practice of autopsies was still very much a new science, examiners managed to uncover a worrying detail upon dissection; the internal organs were blackened by the telltale signs of poison.

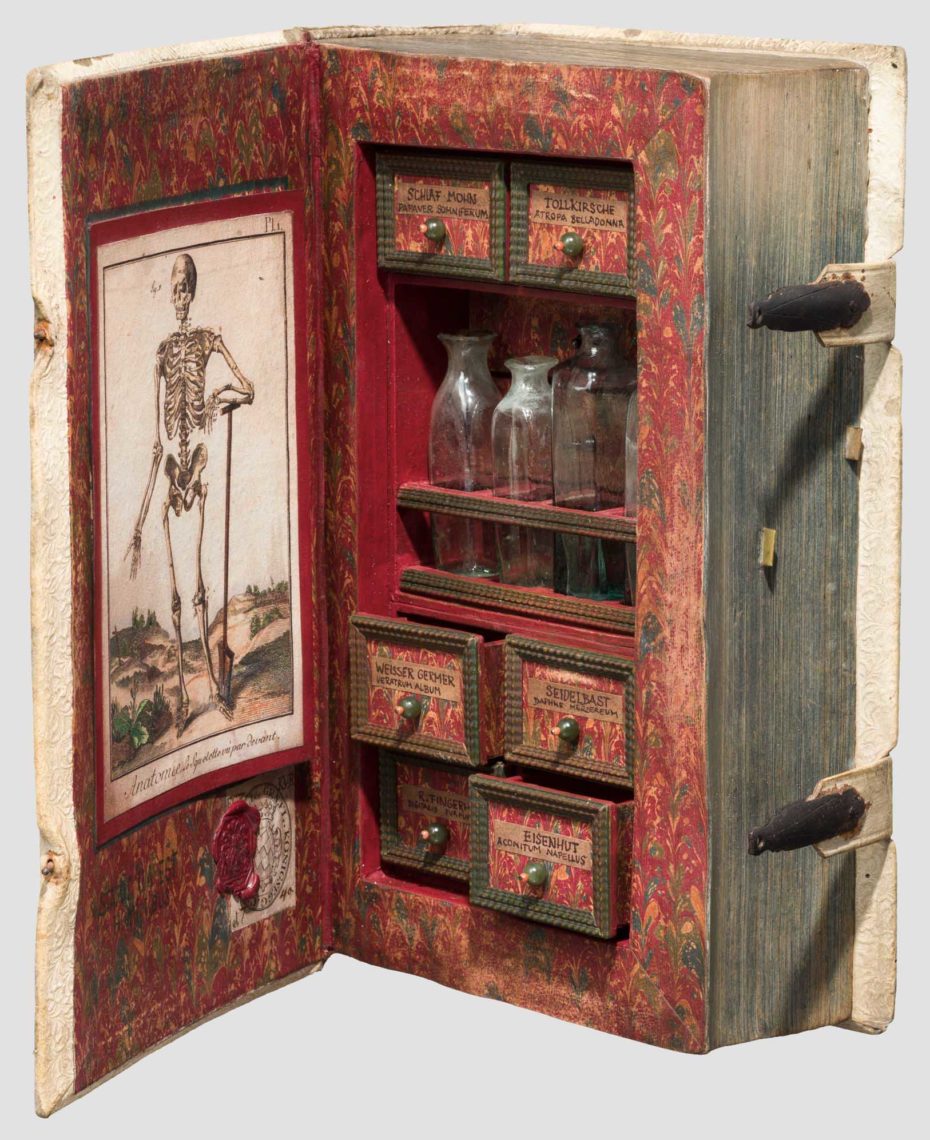

Investigators remained mystified until it came to light that a network of diviners, essentially early modern European pharmacists, had been supplying poison to thousands of citizens. Things got interesting in 1672 when police were called to a break-in at the laboratory of a recently-deceased army captain turned alchemist, Jean Baptiste Godin de Sainte-Croix. Presumed to have died as a result of exposure to his own lethal chemicals, he had left behind a number of clues that would launch an almighty witch hunt among the highest ranks of society. In a red leather trunk belonging to the army captain, a series of letters he’d saved were found detailing dealings of poisonings that incriminated both himself and his lover, a married aristocrat by the name of Marie de Brinvilliers. Marie had gone missing, but she was now the prime suspect in the fatal poisoning of her own father and two brothers.

At the age of 21, Marie had managed to secure herself a financially secure marriage with Antoine Gobelin, the Marquise de Brinvilliers. The union was one of convenience and she soon strayed from her gambling husband into the arms of the dashing army captain Godin de Sainte-Croix. When Marie’s family got wind of the affair, her influential father had Sainte-Croix arrested. Whilst serving his time at Bastille, Marie’s lover encountered fellow prisoner Egidio Exili, a suspected expert poisoner who shared his wealth of experience with a willing Sainte-Croix. Upon his release, he secretly reunited with Marie and began an alchemy business which allowed him to work with poisons. It was in his laboratory that Marie supposedly began plotting her revenge against her family and experimenting with poisons. She would later be accused of killing upwards of 30 innocent people to test out her concoctions. It’s said she found her victims in Paris’ hospitals; the sick and impoverished patients of Hôtel Dieu, next to Notre Dame.

When Marie’s father and two brothers had died of similar causes, all within a very short period time of each other, foul play had been suspected, but it wasn’t until her lover’s laboratory was raided and his letters were discovered that their cases were re-opened and the Marquise de Brinvilliers became France’s most wanted woman. Marie managed to dodge the authorities for a number of years, fleeing Paris and finding refuge in nearby Belgium. After four years, she was found living in a convent and brought back to France despite several suicide attempts en route to Paris. It’s alleged that among her possessions at the convent were letters of her own confession, admitting to her many sins. Her trial captured the attention of all of Paris, and was of particular interest to Madame de Sévigné, whose famous letters highlighted the gossip that spread around French nobility.

Marie was subsequently tortured, found guilty of her crimes, tortured again and beheaded and burnt at the stake – but not before allegedly uttering the phrase, “Out of so many guilty people, must I be the only one to be put to death? … Half the people in town are involved in this sort of thing, and I could ruin them if I were to talk.”

Marie’s bold claims might have been dismissed if half of Paris and its aristocracy hadn’t gathered to witness the spectacle of her execution. The scandal quickly became a hot topic amongst the inner circle of the king. Marie’s last words, coupled with the suspicious deaths at the Versailles court pressured Louis XIV to scramble together a special tribunal to seek out others who might be involved and promptly snuff them out.

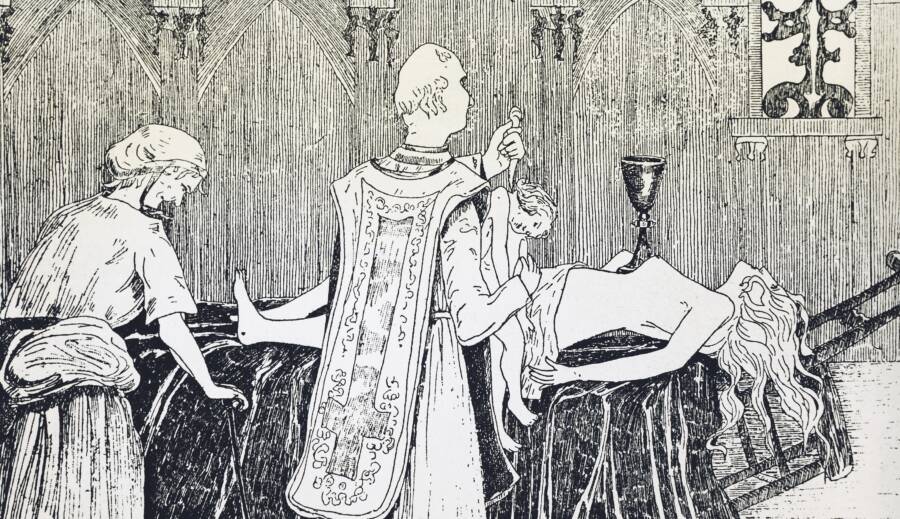

And so, enter Catherine Deshayes Monvoisin or “La Voisin” as she came to be known. A midwife by day, and a diviner (fortune teller), accused sorceress and professional poisoner by night, La Voisin had established a notorious reputation across Paris and beyond for providing her rich, aristocratic clients with poisons, aphrodisiacs, abortions and purported black magic services, including satanic rituals.

In her dealings of illegal abortions, [trigger warning] claims were made that aborted fetuses were burnt at La Voisin’s house and then buried in the garden, but this was never been proven to be true. It’s worth noting that King Louis XIV specifically ordered his tribunal not to delve further into La Voisin’s abortion practice – perhaps for his own convenience.

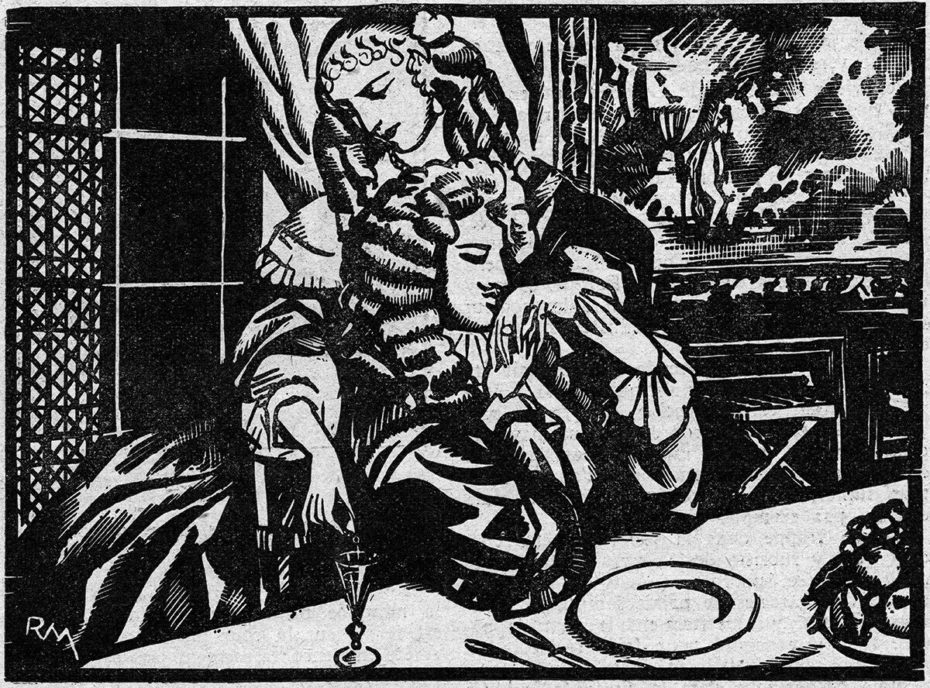

La Voisin’s most famous client was Madame de Montespan, official royal mistress to the king, hailed by some as the “true Queen of France” due to her influence at court during that time. Montespan allegedly became a loyal customer of La Voisin’s after one of her infamous black mass ceremonies appeared to help the hopeful courtier win over Louis XIV’s heart. It’s claimed that from then on, Montespan regularly drugged the king with La Voisin’s various potions and aphrodisiacs to keep his attentions on her and his other mistresses at bay.

According to testimony, the La Voisin repeatedly carried out rituals and called on the devil in blood-soaked ceremonies over Montespan’s nude body at the home of Catherine Trianon, a well-educated diviner who was also an open homosexual, and one of the most important associates in La Voisin’s network. Horrific details of satanic rituals include claims that in order express Montespan’s gratitude to the devil, they sacrificed a newborn’s life, draining its blood, which was used in various potions for the sun king.

When it looked like his eye might once again be wandering, Montespan convinced La Voisin to help her kill the king. The plan was to poison a petition which would be hand delivered to the monarch, but the plan ultimately failed. While planning their second attempt on his life, the king’s witch hunters were closing in on La Voisin’s network of fortune tellers and alleged poisoners. In January 1679, La Voisin’s accomplice, Marie Bosse was arrested, along with fellow poisoner, Marie Vigoreaux. La Voisin was next and it didn’t take long before confessions were drawn for having supplied poison and various black magic services to those within the royal court.

It’s suggested that La Voisin was never subjected to torture for fear that she might reveal the names of influential people, even the king himself. It wasn’t until his former mistress Mme de Montespan ended up being implicated, that Louis chose to shut down the commission to avoid embarrassment. Still, La Voisin was convicted of witchcraft along with many of her accomplices and sentenced to execution by burning. She was suspected to have killed somewhere between 1,000 to 2,500 through her network of poisoners.

Nearly a year after her original arrest, La Voisin was dragged out of her prison and executed in front of a blood-thirsty crowd. Echoing the words of her predecessor Marie de Brinvilliers, La Voisin had proclaimed before her death, “Paris is full of this kind of thing (…) there is an infinite number of people engaged in this evil trade.”

‘The affair of the poisons’ plunges us into a little-known underworld of Paris in the late 17th century, but how much should we be reading between the lines? History has a funny way of repeating itself. Independent, sexually liberated women, abortionists and homosexuals on trial for witchcraft? The facts of this 300 year old conspiracy which claimed twice as many lives as the Salem witch trials remain unchallenged.