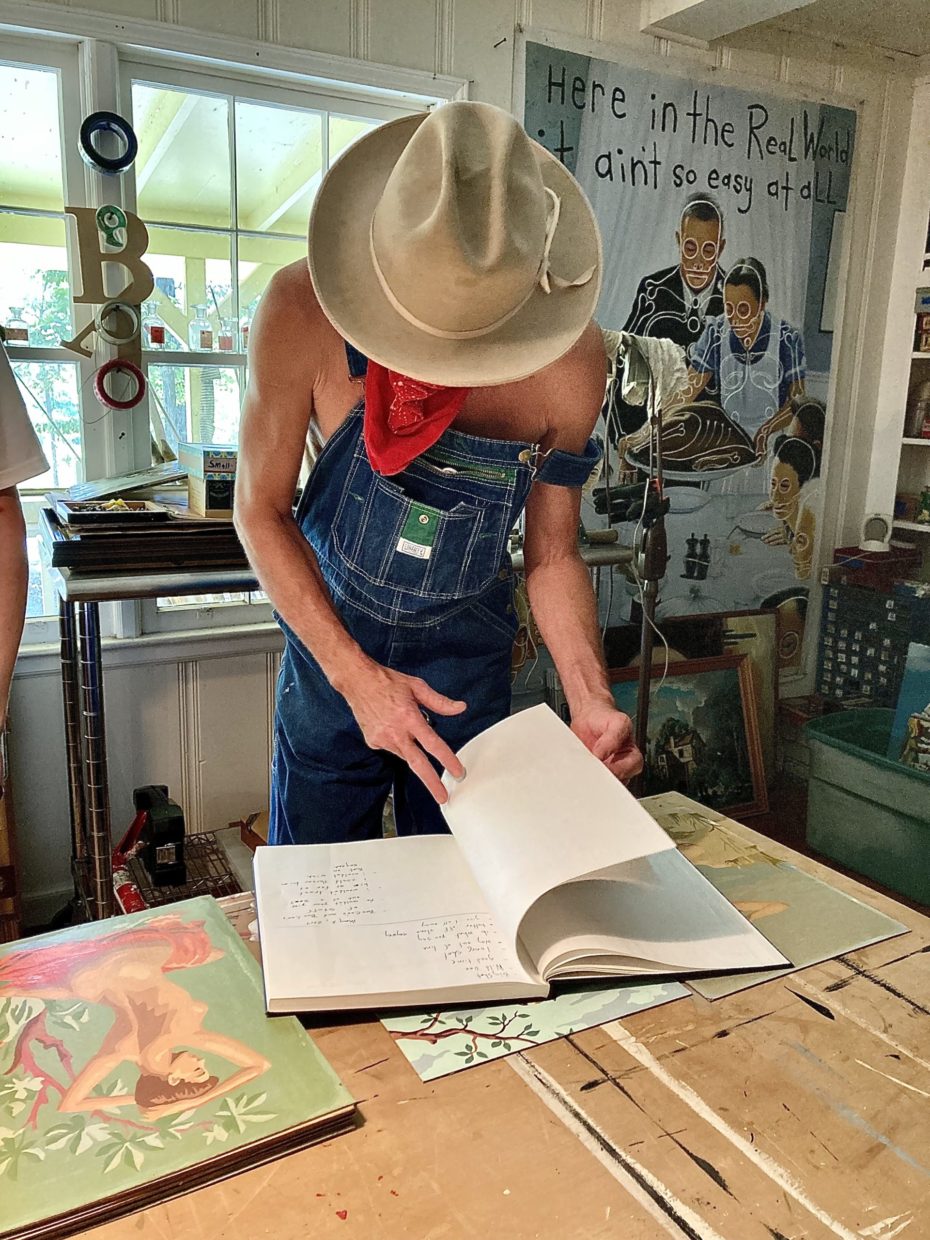

Butch Anthony’s cabinet of curiosities, aka the Museum of Wonder, isn’t easy to find. Beyond the help of Google Maps down these sparse backroads of rural Seale, Alabama, you have to rely on Anthony’s hand-drawn map. There’s no sign, just an ordinary black mailbox. Your one clue that you’ve found the place is the address painted in Anthony’s distinctive hand, which features prominently in his works: neat and clear, a little idiosyncratic and impossible to forget, just like the artist himself. Turning down the dusty gravel drive of his 80 acre property, you pass green fields; dense forest; a small, sandy-bottomed lake; and the occasional twisted metal figure tucked into the tree line. At the end of the drive is Anthony, grinning with classic country hospitality, decked out in Liberty overalls without a shirt, accessorized with a bright red bandana and a straw hat.

You might be forgiven for wondering whether Anthony is serious or whether this is caricature, just another part of the art. And the answer is, like so many things about Anthony, both – yes, he is serious – the wardrobe, the accent, the lifestyle are all authentic. And yes, this is also all part of the art.

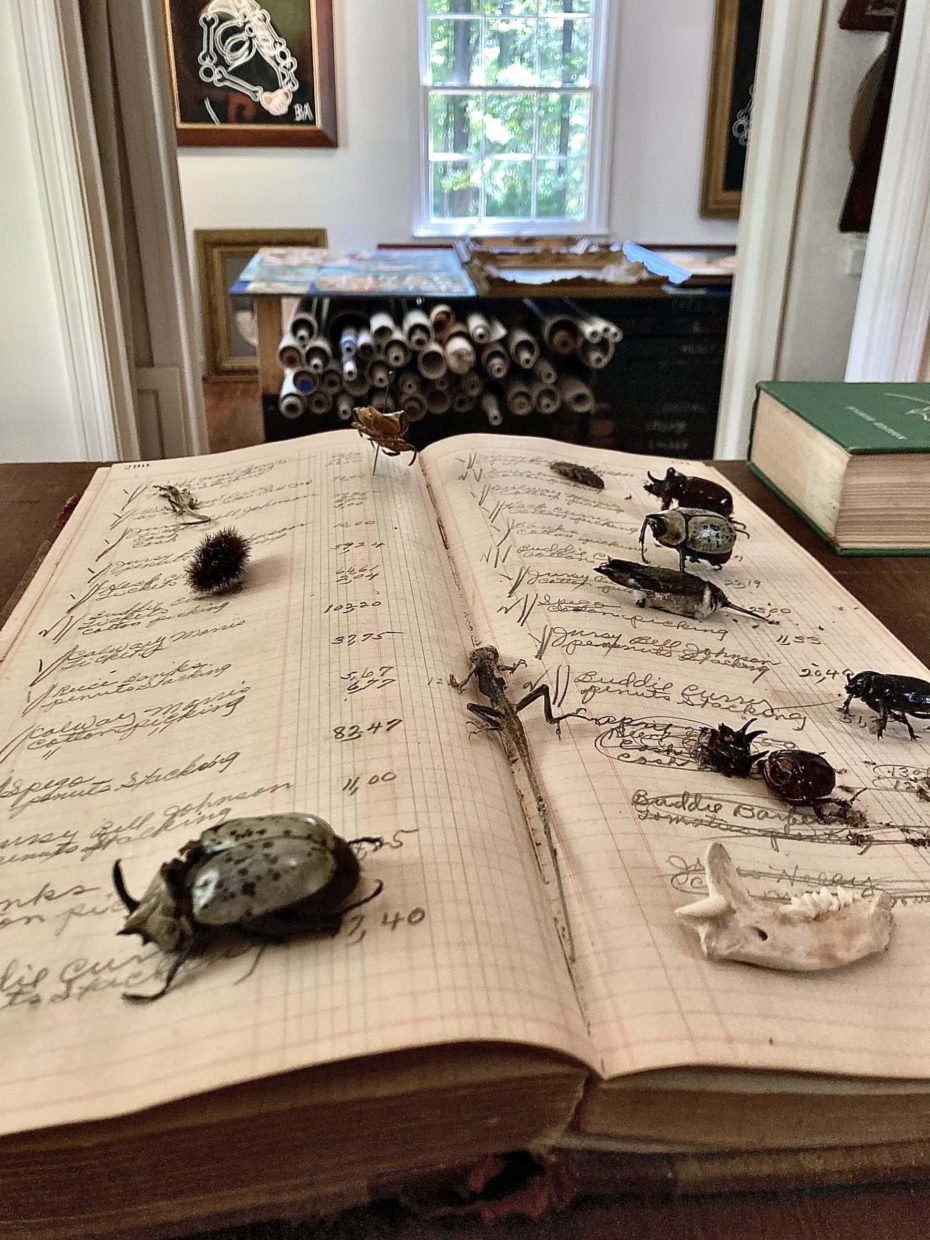

Anthony grew up the way many Alabama boys do: squirrel hunting, searching for arrowheads, exploring the creeks and crevices of this backwoods land. He knows every inch of these woods and fields and possesses an eye for detail and a formidable memory that informs much of his work. As a teenager Anthony was searching for fossilized shark teeth with a friend when he noticed something strange partially uncovered in a creek bank. Fascinated, Anthony dug the bone out of the mud with his pocket knife. The find was authenticated by a geologist at Auburn University as the vertebra of a Mosasaur, a large aquatic reptile from the Cretaceous era.

“I knew it was old, but I had no idea it would be 65 million years old,” Anthony said in a local newspaper article at the time. “I plan to keep on searching for other bones and stuff until I have to go back to school. I’ll probably keep on searching on weekends after that.”

And four decades later, he’s still searching. His own unusual finds form the backbone of many of his more than 10,000 artistic works, incorporating elements of collage, sculpture, storytelling, embroidery and painting. Other people contribute discoveries, too – from vintage portraits to actual roadkill to baby teeth. Once someone sent him a human skull, but Anthony thought it had bad vibes and didn’t want to keep it in the house. His Bone Quilt pieces (fashioned from animal bones, not human) can take up to five years to create; the bones are picked clean by buzzards on the backside of Anthony’s land.

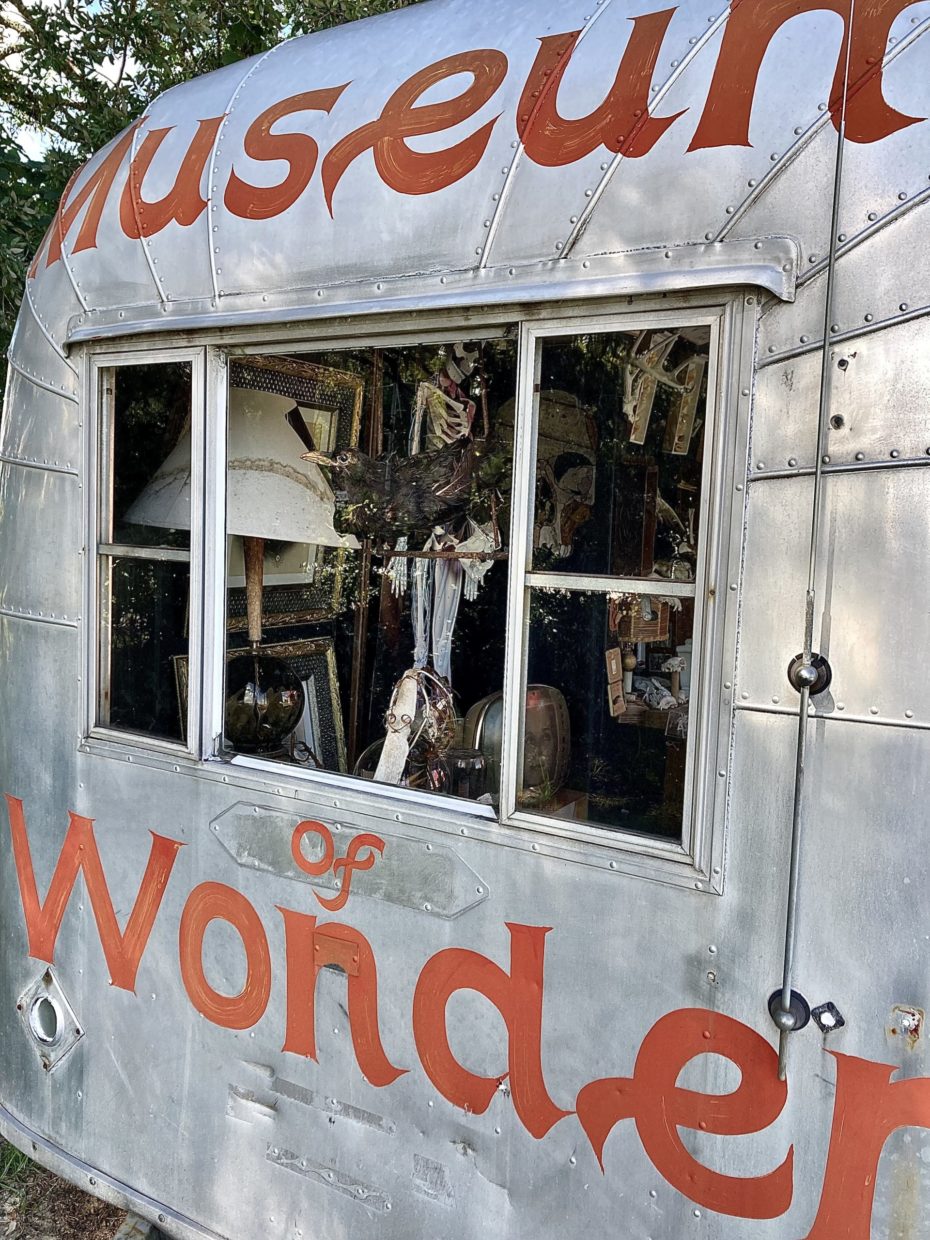

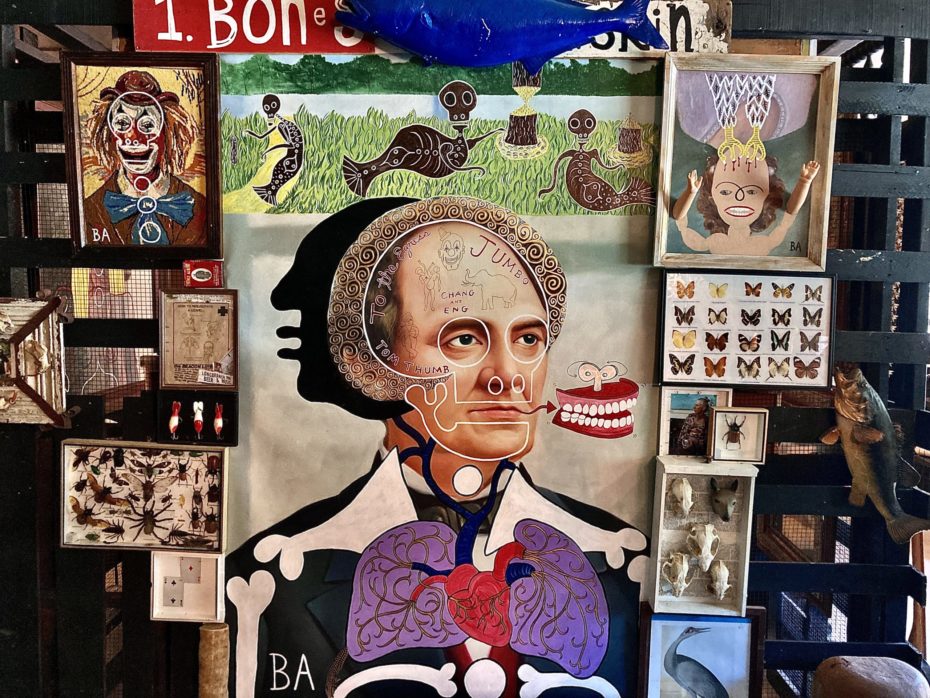

At 14, Anthony hand built his own one-room log cabin, and next door he eventually started a taxidermy shop. Along the way, both became filled with natural and found artifacts and other curiosities, growing into the original Museum of Wonder. On display you’ll find everything from the world’s largest gallstone to footprints from both “Sasquatch” and a “Baby Bigfoot.” This is maximalism on full display with a hefty dose of P.T. Barnum bravado, every wall and corner filled with preserved specimens, jars brimming with tiny bones, a sign that asks simply, “What is it?”

The whole place is infused with Anthony’s wit and knack for a good yarn.

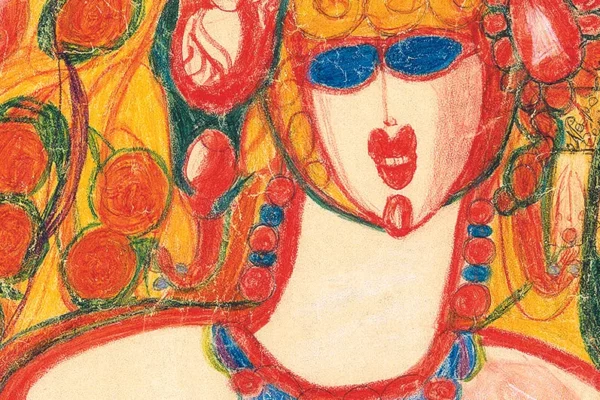

In the mid-80s Anthony attended Auburn University, studying biology, zoology and geology. His resulting understanding of anatomy became a key component of his signature style. But it wasn’t until a decade later that the artistic muse came calling when Anthony’s long-time friend and neighbor John Henry Toney plowed up a turnip that looked like a human face. Anthony told Toney to draw a picture of it and place it for sale at the local junk shop. When the drawing sold for $50, Anthony decided that if Toney could be an artist, he could be one too. His works became increasingly elaborate, eventually coalescing into a style Anthony dubbed “Intertwangleism”. As he explains it: Inter = to mix; twangle = a distinctive way of speaking, thinking, behaving, assessing; and ism = a theory.

The works he’s most known for are his Intertwangled portraits, 19th century photographs or other artists’ paintings over which Anthony paints skeletons and colloquial sayings or quotes he overhears and collects in his journals.

“Every time I hear something weird, I write it down,” Anthony says, opening his current Word Book, as he calls it. “If you stand in the line at Wal-Mart you’ll hear all kinds of things.”

She don’t know me from Adam’s house cat.

Couldn’t pour piss out of a boot.

One of his current Intertwangled portraits is titled “Goddess of the Countryside,” created from an oil painting dating to the 1790s. When he purchased the original painting from the Albany Museum in Albany, Georgia, the staff there expressed some concerns. “They said, ‘You ain’t gonna paint bones on this are you? It’s from 1790!’” Anthony paused with a shrug. “Yeah, I probably am.”

For the viewer with a sense of curiosity and a healthy appreciation for sarcasm, Anthony’s works provide a biting commentary on contemporary American life using objects from our natural and cultural history.

Anthony’s works are displayed from Memphis to Moscow, and he counts among his fans and collectors actress Sophia Bush, pop star Joe Jonas and the late, renowned musician and songwriter Leon Russell. Not long before he died, Russell traded Anthony his 1988 Cadillac for a few pieces. As we bounce down Anthony’s gravel driveway in the car, he motions to the back seat, “Tom Petty had sex right where they’re sitting back there.”

Now the Cadillac has become part of Anthony’s body of work as well. He affixed trophies found at yard sales all over the hood and roof and a deer head to the front grill. Anthony admits that while the car drives great, things can get a little dicey when you’re going over 90 because the trophies start to fly off.

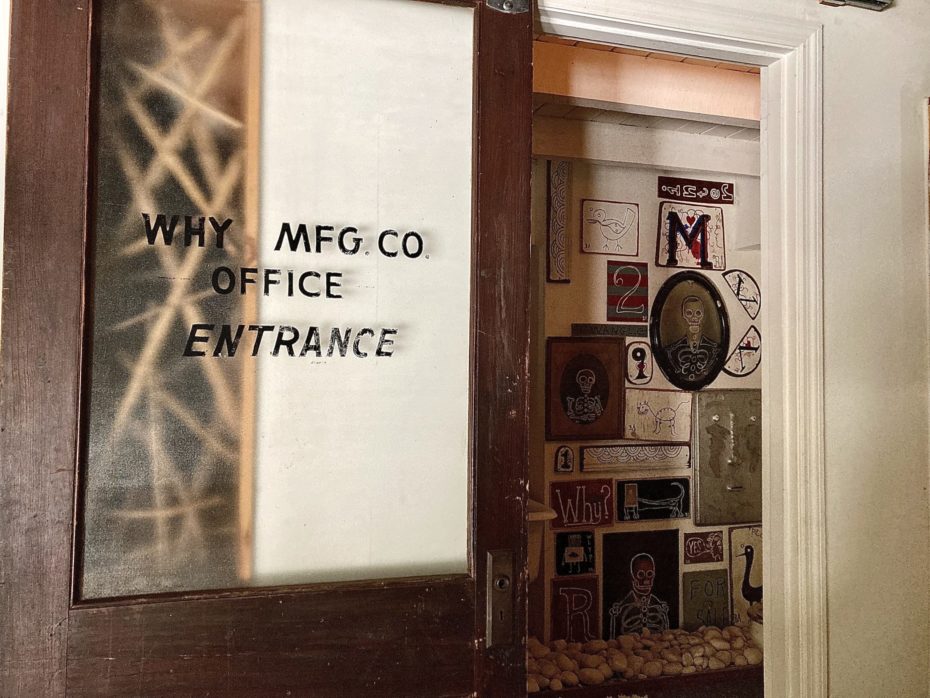

As interest in Anthony’s work grew, the one-room cabin and original museum became too small to contain the artist and his works. He endeavored on a 28-year project to build a new house using reclaimed wood from old buildings and furniture he built himself, then filled it with his art. He also constructed the World’s First Drive-Thru Museum using shipping crates to house a rotating selection of his works and wonders. During the height of the 2020 Covid-19 lockdowns, the Drive-Thru Museum was one of the few museums in the world that remained open. More of Anthony’s pieces are found at the Possum Trot, once his father’s barbecue restaurant and now a gallery. So named for the possum races held out back in the 70s, Possum Trot was host to weekly junk auctions before the pandemic struck.

Self-taught artists, especially those in the rural American South, are often somewhat dismissively labeled as folk artists. But Anthony’s works are alive with intellect and observation, forcing us to consider whether there is really any difference between the fine and the folk.

Learn more about Butch Anthony here. The Drive-Thru Museum is located at 970 Alabama 169, Seale, AL, and is open 24/7. Visits to the original Museum of Wonder, Anthony’s studio and Possum Trot are available by appointment only.