Wander around Lower Manhattan you’ll find perhaps the most beautiful doors in the whole city. Curved and ornately designed in silver and bronze, they are adorned with panels depicting methods of transportation from the golden age of travel: luxury steamships, fleets of sleek aircraft, hot air balloons and grand railroads. Most of the passersby that throng the Financial District pay these magnificent doors little attention; the fact that they rarely open only adds to their anonymity.

But if you were able to step inside, you would discover an exquisite, abandoned Art Deco banking hall that once occupied the ground floor of one of Manhattan’s most elegant, but over looked skyscrapers, Twenty Exchange.

Twenty Exchange can be found filling an unusual city block in Lower Manhattan, bounded by Exchange Place, Beaver, William and Hanover Streets. This is the old part of New York, once inhabited by the Lenape Native Americans, and settled by the Dutch. Instead of the familiar and famous Manhattan grid system, the lower part of the city is made up of alleyways and curved roads that follows the original creeks and streams of the island.

Spend a day exploring the nooks and crannies of what is known today as the Financial District, and you’ll discover all sorts of hidden gems of old New York: the oldest fence in the city; a pair of columns said to be rescued from Pompeii that grace one of America’s first restaurants, Delmonico’s; the grand offices of vintage streamliner companies; the place were Wall Street was still an actual fortified wooden wall; Fraunces Tavern, one of the oldest surviving taverns in the city; and the persevered remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam buildings embedded in the sidewalk. But just as impressive as all of these, is the elegant Art Deco skyscraper on Exchange Place.

When the esteemed New York architectural firm of Cross & Cross were approached by the National City Bank of New York and The Farmers Loan & Trust Company to build their new headquarters, the architects dreamt big. These giants of finance, two of the oldest banks in America, had merged in 1929 to form the City Bank Farmers Trust, known today as CitiBank. The company wanted a suitably grandiose new skyscraper to impose their presence on Wall Street. Cross & Cross’ plan was impressive: they would build the world’s tallest building.

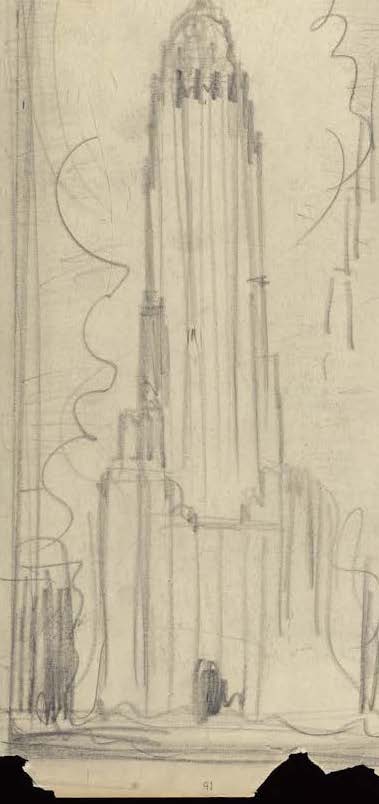

The first hand drawn sketch shows a towering skyscraper of concrete, steel and glass, seventy-one stories tall, topped with an illuminated globe fifteen feet in diameter that would be supported by four massive eagles. A staff writer for the newspaper the New York World Telegram sat in on their original draft meetings for the monolith: “Horizon makers huddled over the table,” reported William Engle, “it is the story of men and steel battling nature….death and gravity…it was the first creative move to rear one of the world’s great skyscrapers.”

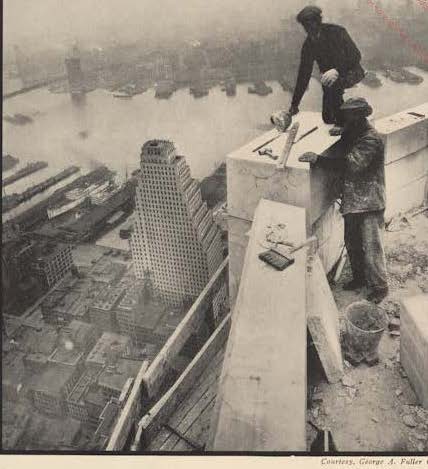

But the grand plans for the skyscraper were swiftly curtailed by the Great Depression, leaving no money for the giant illuminated globe. When it was completed in February, 1931, what would have been one of the world’s tallest buildings had to settle for being the fourth tallest in New York. Cross & Cross may have had their lofty plans scuppered by the Wall Street Crash, but no expense was spared with what they did build; the firm insisting on luxurious materials throughout.

Whilst most modern skyscrapers are built with plain, flat facades, Twenty Exchange speaks to a time when every corner of the building was beautifully designed and crafted. Stand in front of the building on Beaver Street and look nineteen stories up where you’ll find a row of fourteen colossal, Assyrian-inspired heads carved in stone surveying the city below, that wouldn’t look out of place in the Ancient World.

We were fortunate to get a glimpse inside Twenty Exchange with the building’s leasing manager, Robert Beacham, whose passion for the building can be seen in the marvellously curated Instagram account he runs. Entering the main entrance on William Street, customers and employees of the City Bank Farmers Trust were greeted by a spectacular rotunda.

Measuring thirty-six feet across, framed with red marble columns, and decorated with silver Art Deco motifs of telephones and ticker tape machines, it was designed to impress: this wasn’t simply a visit to a branch of your local bank, it was the grand entryway into a cathedral of finance and security. The rotunda was lit by a vast illuminated sphere, lit by a hidden crawl space high in the ceiling.

Leading off the rotunda is the main banking hall, decorated with a giant mural in the WPA style. More marble can be seen throughout the beautifully designed banking hall: all told, Cross & Cross used forty five types of exquisite marble, all but three of which were imported from abroad.

The bank managers’ offices were given a similar grand design: the dark woods, secret doorways, grand fireplaces resembling more the library of an English country mansion than a hotbed of Wall Street finance.

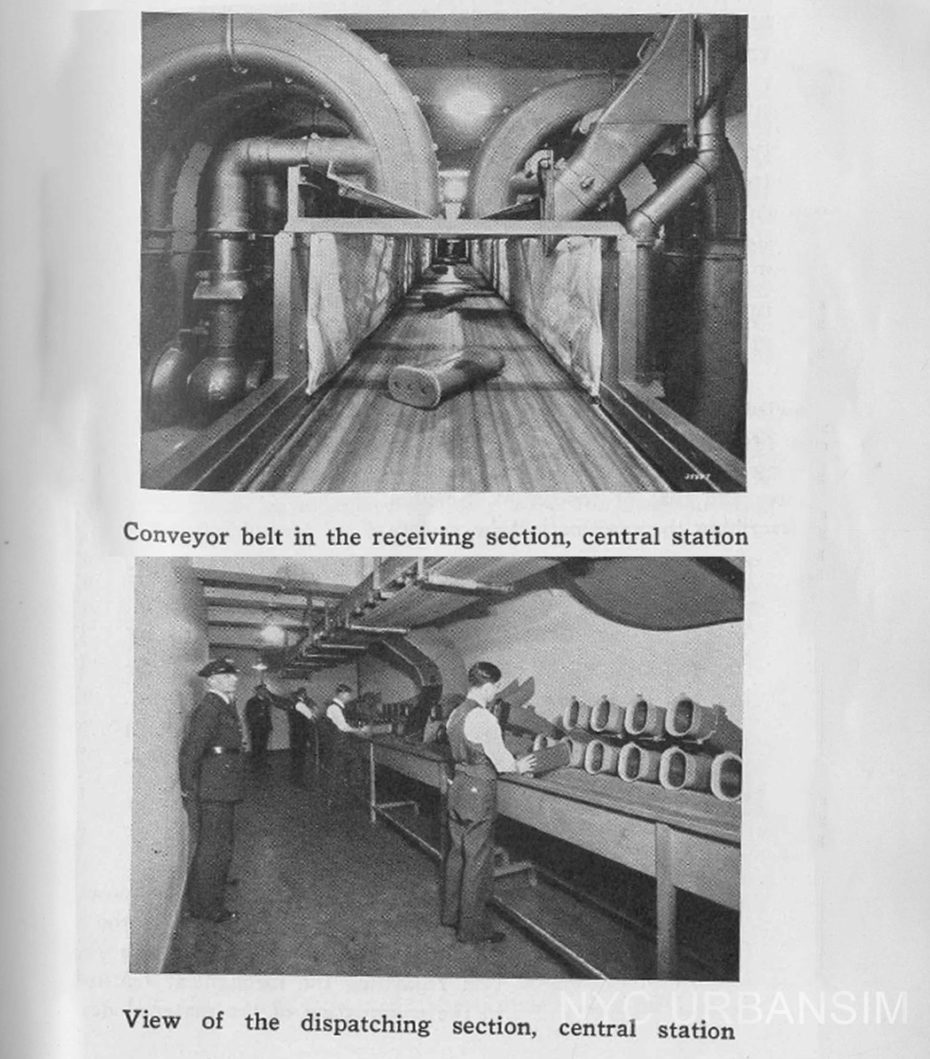

But for all its classical grandeur, Twenty Exchange was also designed to be the height of modernity. The entire fifteenth floor was given over to the largest telephone exchange in New York, whilst buried in the hidden spaces of the skyscraper lay a complex pneumatic tube system for delivering mail and money.

There were thirty one elevators, eight of which operated at the then highest speed permitted by New York City law. Not content with offering refrigerated and ‘ozonited’ water to every floor, the building also pumped soap to each bathroom. No wonder that writer W. Parker Chase, in his 1932 ‘New York – The Wonder City’ recorded that “Everything in connection with this monumental building expresses beauty, completeness and grandeur…the building throughout is the very last word in all that spells DELUXE!”

Parker Chase urged that ‘no one visiting New York should fail to visit…this magnificent and beautiful pile of marble, stone and masonry.’ Words that were taken to heed when the building opened on February 24th, 1931, when the New York Times reported that an astonishing 3,851 people per hour came to marvel and the wonderful new addition to the famous Manhattan skyline.

But today, the once busy banking hall lies silent. Recent years have seen many of Wall Street’s finance companies move either up, or out of town. City Bank Farmers Trust left their deluxe building in the 1970s, leaving the ornate, gilded bank tellers windows to lie unused, the basement vaults empty of money.

Today, many of the Financial District’s vacant skyscrapers have been repurposed into apartments, including Twenty Exchange, giving downtown dwellers the opportunity to live in the some of the most elegant Art Deco buildings ever made. One of Twenty Exchange’s most infamous residents was the KGB spy, Anna Chapman, who was living in the building when she was arrested in 2010 as an “unregistered agent of a foreign government”. Although rarely visited by the public, the ornate banking hall on the ground floor has seen new lease of life as a film set, appearing in films such as Wall Street and Spider-Man 2. The rest of the time, it lies unused, lying hidden behind the beautiful silver doors.

In a city known for its skyline, Twenty Exchange is perhaps eclipsed by some of the most famous skyscrapers in the world, such as the Empire State, Chrysler and Woolworth buildings, but it remains a hidden gem of Lower Manhattan, waiting to be discovered.