When English ceramic artist Clarice Cliff first started designing pottery in the 1920s, her work was so out there, the styled garnered the name “Bizarre.” But the curious and colourful decorative pieces with abstract shapes and pastoral scenes soon gathered an impressive following. Ahead of her time, Cliff’s rise to fame during the mid 20th century was unexpected, not only because of her gender, but also her modest background. Having started at the very bottom, she was one of the first women to produce a line of crockery under her own name, and today, not only is Clarice’s work is highly collectible, but she is soon to be the subject of an upcoming film biopic The Colour Room, starring Bridgerton’s Phoebe Dynevor. We thought this might be a good time to become more familiar with her story and her delightful ceramics…

Born in 1899, Cliff grew up in a working class family in Tunstall, a town known for its pottery factories. She was inspired by an aunt who worked as a hand painter at a local pottery business and began working in the industry at the age of 13. Cliff later said, ”there is little to do on leaving school except to work in a factory.” She began as a gilder, adding lines of gold paint onto traditional pottery designs. (As an apprentice, her salary was minimal and compensation was based on how many pieces she finished). She eventually advanced to become a freehand painter while also studying art and sculpture at night.

While most young women focused on gaining one skill, Clarice decided to master the entire pottery process. During this time, she began developing a relationship with factory owner Colley Shorter, who became impressed by Clarice’s work and helped influenced her decision to attend the Royal College of Art in London. (Shorter, who was 17 years older than Cliff, would also eventually become her husband).

She was given her own studio in 1927, where she decorated defective pottery with on-glaze enamels that resulted in a range of bright shades. A senior salesman was shocked when he took a load of Cliff’s pieces with simple triangle shapes to a large stockist and they were an immediate hit. Unique for her time, Cliff was given credit for all of her work, with her brand marked on each piece, making her one of the first women to have a line using her own name.

As her style evolved, Cliff’s work became inspired by Art Deco, incorporating abstract principles into her “Fantastique” range. In 1928, she produced what would prove to be her signature design: the “Crocus,” with handprinted flowers in blues, oranges and purples. As the Victoria and Albert Museum, which is now home to many of her pieces, explains, “Each flower was composed with upward brush strokes, then green leaves added, by holding the piece upside down and painting thin lines among the flowers.”

Cliff was soon able to have a whole team of about 70 helping her produce work, known as the Bizarre Girls (and boys). Despite the economic recession, she continued to be successful because of her product’s more accessible price point. As the V&A Museum points out, she was successful in adapting the cutting-edge Art Deco aesthetic to the domestic sphere, in practical cups, plates, jugs, tea cups, you name it.

During this period, she also began experimenting with the most pleasing ways to display the designs on dishware, whether it be a sunburst, a country cottage or a butterfly. Unique designs included a cone-shaped sugar shaker and an autumnal double inkwell.

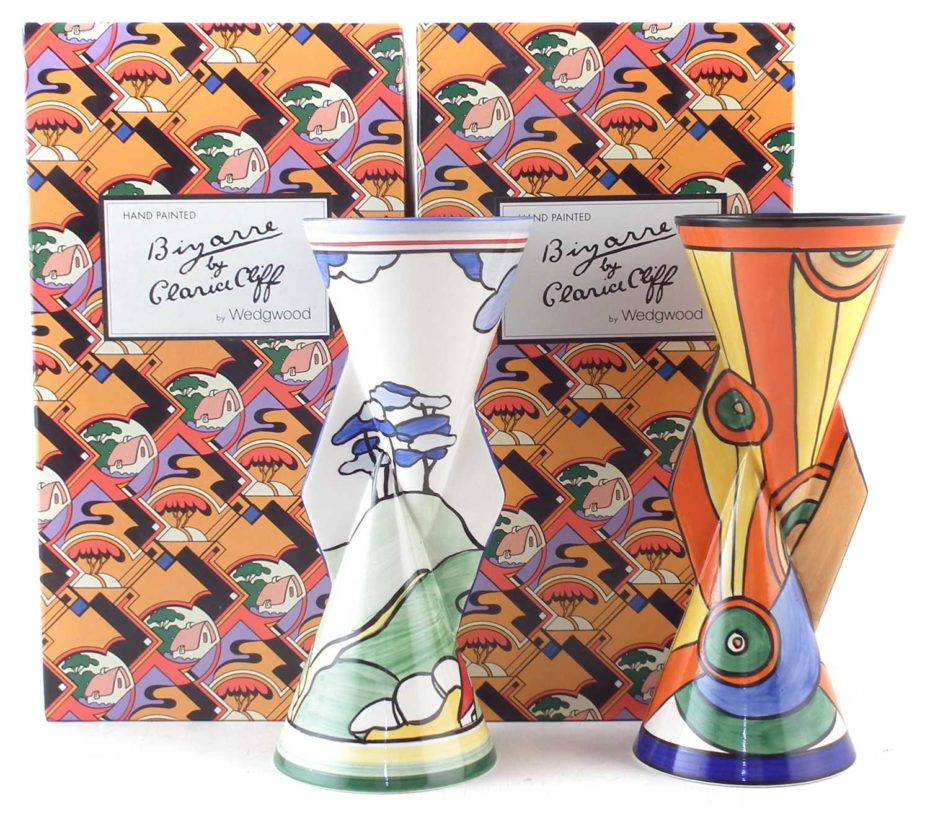

Some of her most creative shapes came in vases, whether it be a stepped vase inspired by Cubism, a Yoyo vase using her favourite cone formation or one drawing from Pablo Picasso’s flower illustrations. The Spanish painter wasn’t the only artist to influence Cliff. “She was inspired by the major art movements – she was looking at artists like Mondrian, Modigliani, the major Bauhaus movement – she was completely on point,” says auctioneer and design specialist Will Farmer. “New trends that were happening in London and Paris, she transformed them into everyday domestic wares.”

By the 1930s, Cliff was a feature in national media for her pioneering role and her pottery was being exported around the world. (As a local paper noted, she may have been shy, but she fit the look of her period, with a cloche hat and cigarette). She continued to largely hire women, with her decorating apprentice Ethel Barrow training 20 other female potters. Clarice married Colley Shorter in 1940 and while she was able to continue production during the war years, limited supplies meant she could only produce basic white potteries. After World War II, a shift to more conservative styles led to her stepping away from design, and following her husband’s death in 1963 she sold her factory and retired.

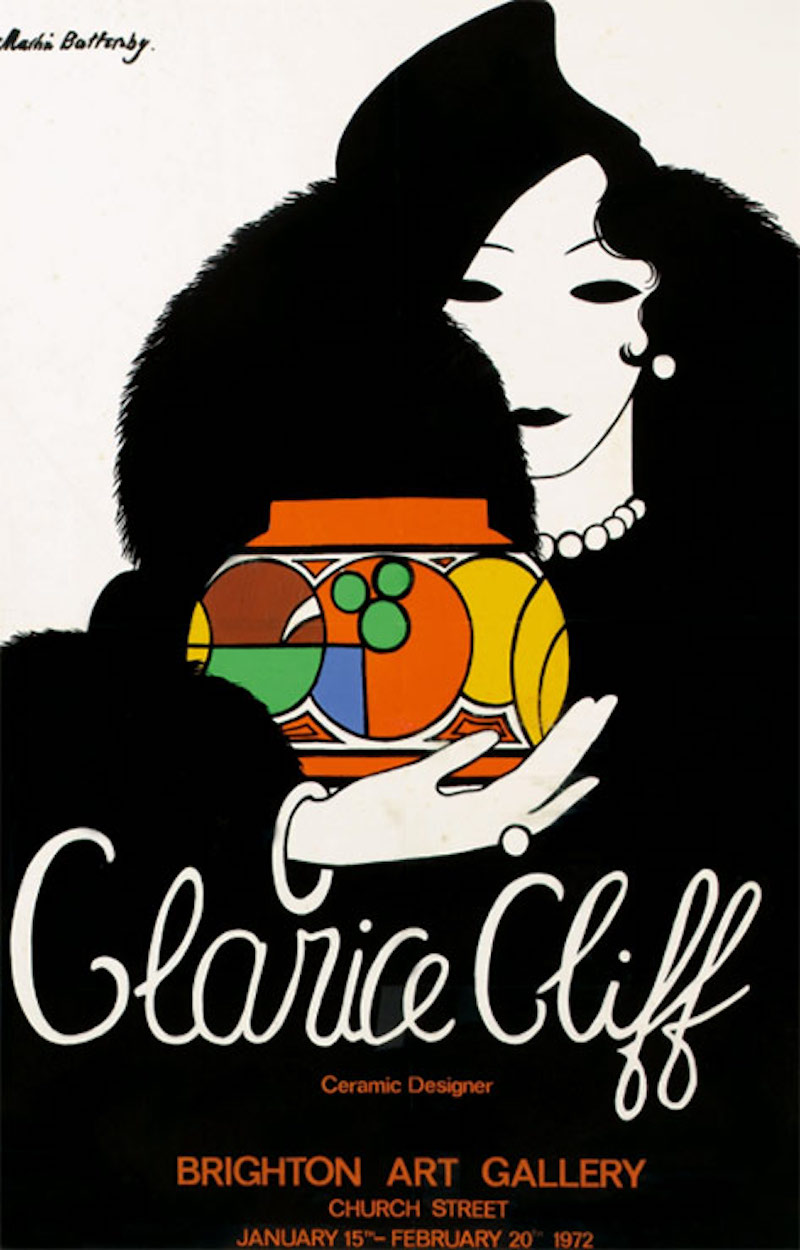

While a revival of her work took off in the 1970s, with the first exhibition of her work in Brighton, Cliff passed away suddenly in 1972. Still, her popularity, and the value of her pottery, only continued to grow, with Christie’s hosting its first Cliff auction in 1983. In 2003, Christie’s sold “May Avenue” — a rare charger inspired by an Amedeo Modigliani oil painting — for a whopping £39,950. Although, staying true to her humble roots, the name of the work was inspired be a street just a few blocks from her birthplace. The more everyday collectors can still find her work popping up for more reasonable prices on eBay.

Now, Cliff’s legacy is being remembered in the new film “The Colour Room.” Scheduled for cinematic release this year, the biopic “follows the journey of a determined, working class woman… as she breaks the glass ceiling and revolutionises the workplace in the 20th century”.