“Iceberg, Right Ahead!” It’s hard not to think of the iconic line from the film Titanic as the boat we’re sailing in plows forward through the freezing North Atlantic Ocean, heading directly for a vast iceberg. But whilst most vessels try to avoid these frozen giants, our captain is not only seeking them out, but trying to get as close to one as possible. For this voyage is not so much perilous as pleasurable. Our mission: to gather part of iceberg that is an astounding 10,000 years old and put in a cocktail! This is the story of how to make one of the worlds’s most unusual drinks, with perhaps the oldest ingredients imaginable: iceberg vodka!

The eastern coast of Newfoundland and Labrador is a wild and beautiful place, its rocky coastline marked with mysterious sounding remote places like Chimney Tickle, Joe Batts Arm, Seldom Come By, Cut Throat Island, Pick Eyes and Heart’s Content. It is also home to what is known as Iceberg Alley: a peculiar natural phenomenon that occurs each spring, when enormous icebergs detach themselves from the coast of Greenland and guided by a particular current, slowly make their way past Newfoundland and Labrador.

Sometimes these breathtaking giants drift so close to the shoreline, that they tower over the nearby houses perched on the rocks. But whilst most people are content to marvel at the beautiful icebergs from the shore, others are more adventurous. Bravely plunging into the icy water, their job is to harvest as many icebergs as possible before they melt and disappear forever, and use the water to make vodka.

Getting close to a large iceberg is an awe-inspiring moment. The one we pull up against is roughly the size of a football field, and so flat, you could land an airplane on it. Up close, the old saying ‘the tip of the iceberg’ takes on a more menacing meaning, when you realise that there’s 90% more of it hidden under the water, as hard as rock, and able to slice through steel. Others are towering ice sculptures, carved by the Arctic winds and seas into beautiful shapes, spirals and arches, glistening white with aquamarine stripes.

Like most of the icebergs drifting down Iceberg Alley, this one started off as snowfall that settled on the Western Greenland during the last Ice Age. Ten to twenty thousand years later, it had formed into the edge of a glacier that fell into the ocean, before making its steady way southwards. The captain of our vessel breaks off a chunk of the iceberg, filling first an ice cooler, and then my cup. It’s incredible to think that you’re about to have your drink chilled by a mammoth icy relic from a time when there were still mammoths walking the Earth.

The first thing you notice sipping on the ancient ice is that although it has just come from the sea, there’s no salty taste. The other, is that it’s quite wonderful. As our guide from the Iceberg Vodka Corporation explains, “Icebergs are a fantastic source of naturally pure water. Trapped in glaciers 10,000 to 20,000 years old, they are very low in mineral content and that makes for a fantastic blending spirit.”

This small piece of ice in our cup was frozen at a time long before the Industrial Revolution; free from pollutants, it is perhaps the purest source of water on the planet, and is why catching them before they melt is big business. They’re calling it the “white gold rush”. Fancier Canadian restaurants will serve you iceberg water at your table, whilst some makes its way into beer, but it is the clear, pristine vodka remains our favourite. Captain Barry Rogers, owner of Iceberg Quest Ocean Tours in St. John’s, who will sail you dangerously close to an iceberg, simply sprinkles rum over the 10,000 year old ice. “Where else would you get to consume something that’s from the Ice Ages?”

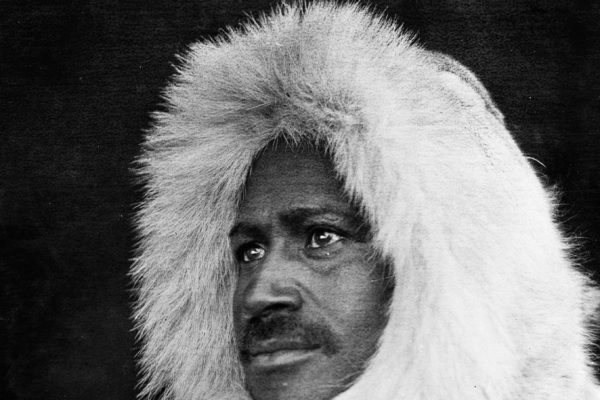

Captain Ed Kean, who quit the fishing industry some 20 years ago to become an iceberg hunter, is the undisputed king of the niche trade. “I come from generations of experts in the marine business,” he explains, “but I’m the first iceberg cowboy in my family. Growing up on the coast and being surrounded by fishermen, I always knew I would end up working on the water in Newfoundland.”

Each year about 40,000 large icebergs will break off from Greenland’s glaciers, but only 400-800 will make it as far south as Newfoundland. And the Iceberg Cowboy will try to harvest as many as possible before they melt away, catching some in nets, or with the giant crane attached to his boat. Sometimes he’ll simply blast away at one with his shotgun. Hunting the icebergs is a race against time. “They come here and they melt so fast,” he explains. “In Newfoundland, they’re like a fallen leaf. They’re going to die in a couple of weeks and be gone back to nature anyway.” The first icebergs enter Iceberg Alley in the Spring, but most will have gone by early summer.

Iceberg hunting is also highly dangerous. “Icebergs can be unpredictable, which makes them difficult to navigate around safely. They can flip or collapse at any time,” warns the official newfoundlandandlabrador.com website, who have even created a safety guide for intrepid sailors and kayakers who want to get up close to the ice age giants.

Take it from these explorers who were very lucky to avoid a fatal accident after climbing onto an iceberg in Svalbard which flipped over…

“When viewing icebergs from the water, it is recommended that you maintain a safe distance (D) – equal to the length of the iceberg (L), or twice its height (H), whichever is greater. Within this perimeter, there is a risk of falling ice, large waves, and submerged hazards. Safety should always be your first priority.” The hazards involved shouldn’t be underestimated: it was just 400 miles away that the Titanic sunk. But the risks don’t deter Captain Kean who aims to collect tens of thousands of litres of ‘white gold’ each year.

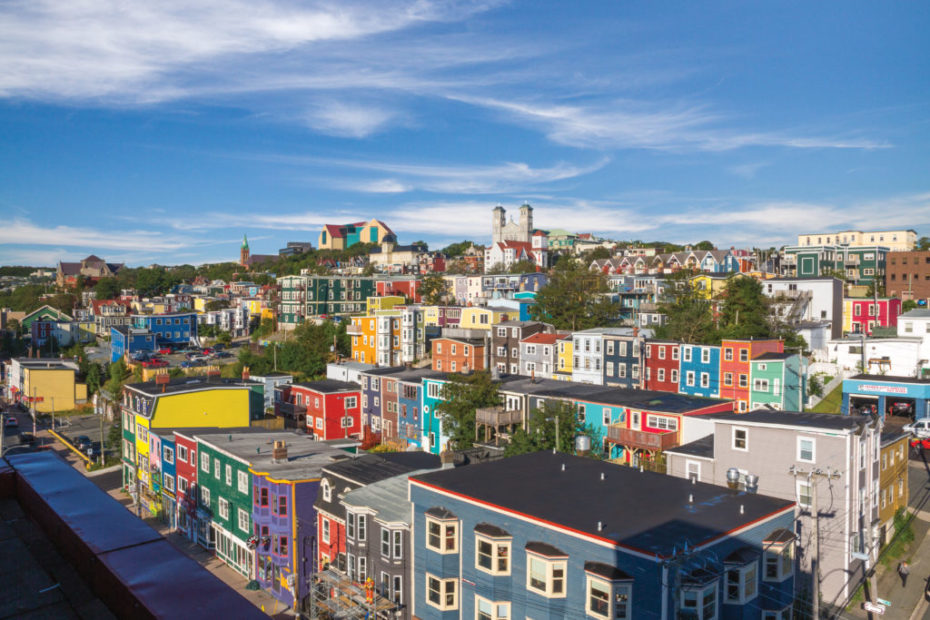

Headquarters for making Iceberg Vodka is in the quaint and beautiful city of St. John’s, Newfoundland. The most easterly city in North America, it is also one of the oldest. John Cabot first sailed into its natural harbour in 1497, whilst in 1583, sea dog Sir Humphrey Gilbert claimed the land as England’s first colony.

A beguiling city in one of Canada’s remotest provinces, one traveler in 1872 described it as ‘a queer place, full of heights and hollows, corners and angles.” Visiting today, the first thing noticeable in the city are some of the steepest streets in North America, rivalling even San Francisco. The other is how the wooden houses are all painted in vivid, bright and nautical colours such a ‘harbour deep’, ‘bubbly squall’ ‘glitter storm’ and ‘hard tack’, drawn from the palette of the Historic Colours of Newfoundland.

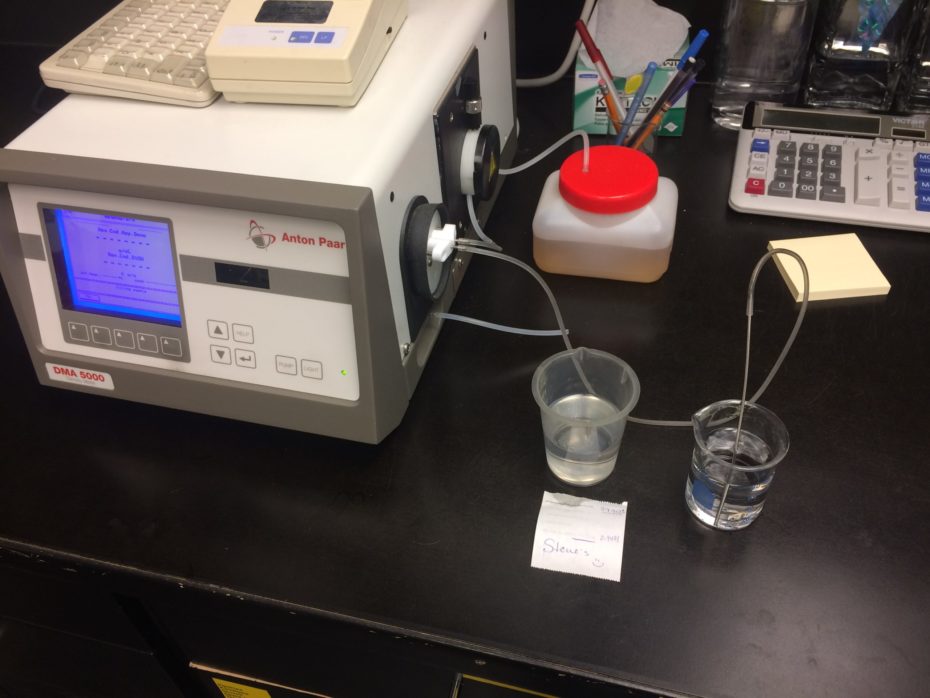

Iceberg Vodka has been made here since 1995, in a facility which is part bottling machinery, part laboratory. Here, the icebergs bravely harvested by Captain Ed Kean are allowed to melt naturally. “The stage from ice to water happens with time,” explains our guide, Tarah Mowry. “You just let it happen. Ed goes out to harvest chunks of ice that get ground up into smaller chunks and then you have to wait.” An iceberg can take a long time to melt into water. “Part of the reason it doesn’t melt is that it was frozen above 0’C. Because of the purity of the water, the mineral content is so low it behaves differently to tap water.”

Once the icebergs have melted, the water is meticulously blended with a triple distilled neutral spirt made from Canadian peaches and cream corn. Each batch of the vodka is then handcrafted, using carbon to purify the spirit. “This is done the old fashioned way,” explains Mowry. “Adding powdered carbon basically attaches itself to any impurities in the water, which are then filtered out removing them from the vodka.” The labs perform a chemical analysis, checking the PH levels and the purity of the spirit, whist sensory evaluations check the quality of the vodka before it can be bottled.

The spectre of climate change and its effect on Greenland and the shrinking polar icecap is hard to ignore, but the makers of iceberg vodka stress that their process isn’t affecting the environment, as they’re only using icebergs that have already broken off from the Arctic Glaciers, and not harvesting intact glaciers from further north. “They’re everywhere,” explains Mowry. “We’re not hurting the environment, we’re just utilising the purest water we can get”.

Drifting icebergs as we all know cause shipping hazards, but they can also change the marine ecosystem as they lose huge volumes of cold fresh water and contribute to rising sea levels. Proponents of the iceberg harvesting idea argue that since the fresh water they contain is wasted in any event, it could instead be utilised.

And so each year, as winter turns to spring, the colossal floating ice sculptures continue to break off the coast of Greenland and slowly make their way past the coastline of Newfoundland and Labrador. The closeness of these frozen giants will leave you awe inspired; and tiny fragments of them might just make their way into your vodka martini that evening, a cocktail some 10,000 years in the making.