The Miramar Hotel is falling down. Its voluptuous domes and towering spires have crashed to the ground, its red roof tiles have been slipping and the classically-moulded plaster on its walls reduced to dust. This once awe-inspiring piece of architecture lies prostrate, with its dismembered limbs on display in the breeze of the balmy seaside town of Macuto flanked by the spectacular Mount Avila ‘the Mountain of Flowers’, close to Caracas, the largest city in Venezuela.

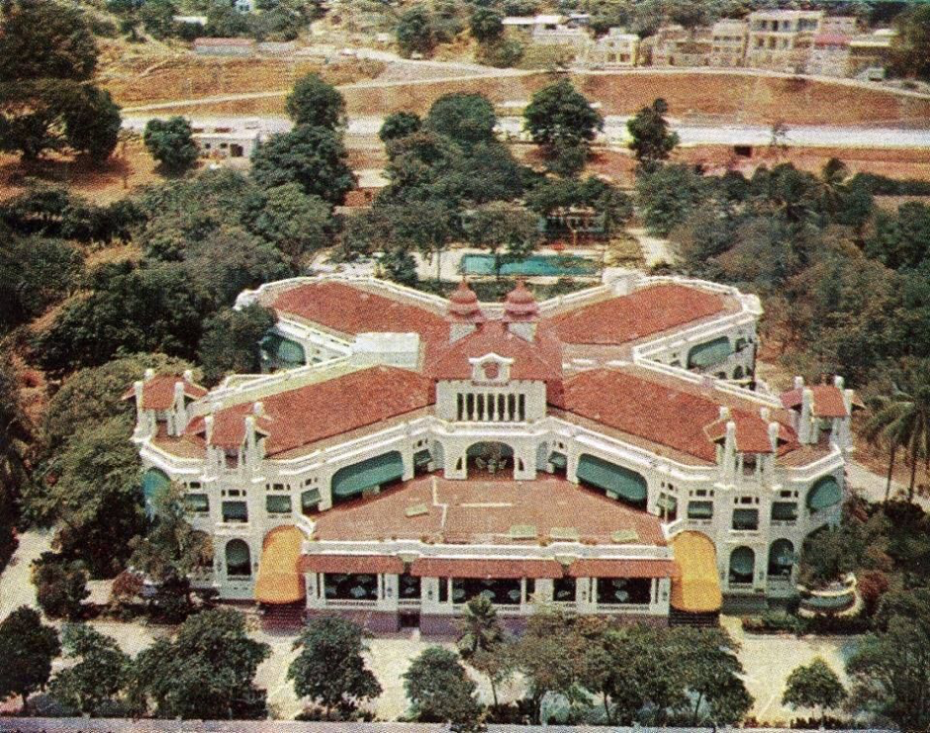

It still overlooks the sparkling azure waters of the Caribbean Sea, just like it did at its conception in 1926. Today, however, it’s a bittersweet landmark, a shell of its former glory, occupying the crossroads between Avenida La Playa and Calle San Bartolome in the spa town of Macuto. It’s off-limits, structurally unsound and not safe to the public, yet curiously still considered a treasured national monument in Venezuela.

At this point, allow us to put you in the picture: Macuto was founded in 1740 on the site of a native village in the 19th Century and soon developed as a charming coastal town with wide streets and grand buildings, a sought-after vacation spot for politicians, presidents and despots alike, where the idle rich would rub shoulders with the politically powerful in the early 20th Century. As the ultimate jewel in Macuto’s crown the outrageously decadent Miramar Hotel was hallmarked to serve this affluent market.

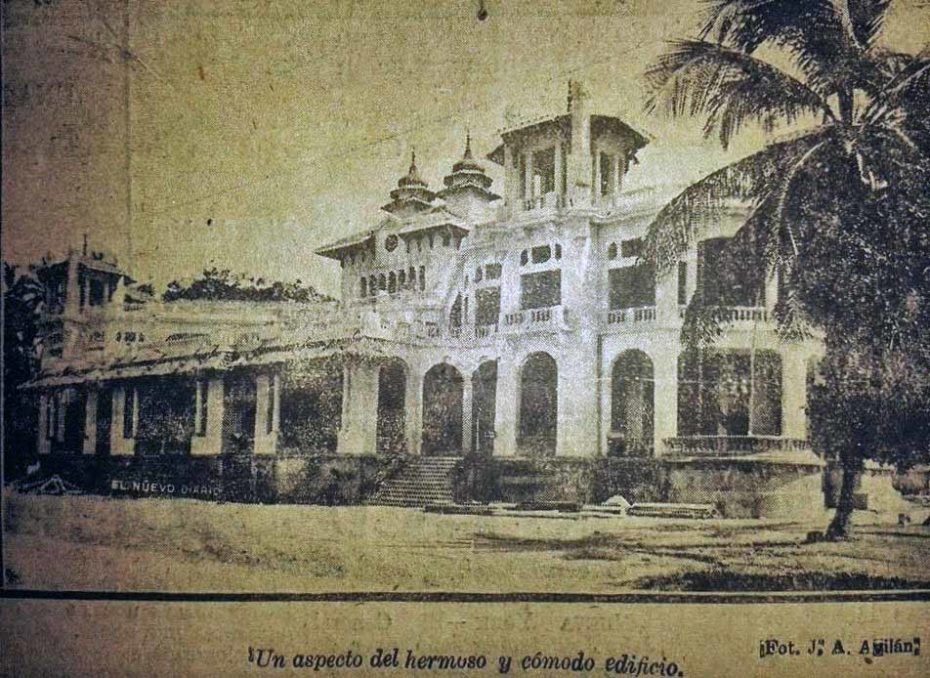

Architecturally the Miramar Hotel was a tour de force in the French grand ‘Beaux-Arts’ style: an audacious and confident singular structure, dripping and encrusted with bold classical iconography. The design was pitched somewhere between 19th Century grand Spanish town halls, splendid railways station frontages and the Roman Emperor Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, Italy. This double floored cruciform-planned palace was lined with columned galleries and crowned with flamboyant skyline towers that broadcast exclusion, privilege, power and wealth. Furnished with spas, games rooms, a grand dining hall, swimming pools and tennis courts, it was created for one set in society, and one set only: the rich, ruling and powerful elite.

Alejandro Chataing, an eminent and prolific Venezuelan architect who built many large scale public buildings in a similar, swaggering style was commissioned to design the Miramar. He was known as ‘the great constructor of the regime of Cipriano Castro’. (Castro had died in 1924, after leading the revolution in 1899, the first of a string of military gangster despots). In 1925, the most notable of these despots, a power-hungry Juan Vicente Gomez, with gravely ambitious plans for the town of Macuto, arranged for the construction of a grand new hotel. Chataing jumped at the opportunity and submitted the winning design under the pseudonym ‘Miramar’. Construction started in 1926 and was completed in 1928.

In the mid 20th century, Venezuela was considered a rich country. It produced more than 10 percent of the world’s crude and had a per capita GDP many times bigger than that of its neighbors Brazil and Colombia, and not far behind that of the United States.

But as power and politics left Macuto by the late 1960s, the once revered Miramar Hotel was simply left to disintegrate. For a fleeting period (in 1974) it was half-heartedly used as a museum but was finally abandoned in 2001. In danger of collapse, five different plans have been submitted for its recovery from 1999 to date, including its use as a Latin American film school. None of those plans have materialized.

Could Hotel Miramar ever be restored as “The Ritz” of Venezuela’s Caribbean riviera? The current state of Venezuela’s hospitality industry is fragile to say the least. Tourism fell by 71% in 2020 and before the pandemic Travel Weekly spoke to Esteban Torbar, a travel agency owner based in the capital, Caracas.

“It’s an extremely destructive business environment,” said Torbar. “Inbound tourism is ‘dead,’ … No one is coming to Venezuela to do business, nor is there much domestic or outbound corporate travel.” Still he seemed hopeful for the future and described Venezuela as “a huge, dormant tourism monster. Amazing islands and beaches, friendly people. It will wake up, not by design but by default”. Drawing comparisons to Colombia’s post-narco recovery, Torbar told Travel Weekly, “We are heading toward one of the most amazing reconstruction processes in history.”

Then the pandemic hit. According to the International Rescue Committee (IRC), Venezuela is now “the world’s second-largest external displacement crisis, just after Syria.” As of July 2021, approximately 1,800 to 2,000 people a day have been leaving the country.

As of January 2019, the United States and Venezuela have no formal diplomatic ties, but continue to have relations under Juan Guaidó, who serves in an imaginary capacity as disputed interim president recognized by around 54 countries, including the United States.

In May of 2020, Hotel Miramar’s resort town of Macuto was one of the sites of the failed Operation Gideon, involving a small group contracted by an American mercenary company that attempted to invade via sea to capture disputed dictator, President Nicolás Maduro, and remove him from power. Eight of the mercenaries were killed, with another thirteen, including two Americans, captured.

In its current state, the old Hotel Miramar seems to embody the abandonment of democracy in Venezuela. It’s listed as a National Historic Landmark, but has no use, is not repaired and is simply decaying. All the fortified, once flamboyant and showy concrete-and-steel structures could not save this grande dame, nature has reduced the cement to sand and the iron to rust. Today, it’s a curiously spectacular post-apocalyptic ruin – a vast, crumbling, monumental piece of sculpture from a bygone era, occupying its position like a concussed alien spaceship that lost its way.