Centuries before Betty Friedan and the sexual revolution challenged social mores in the West, the women of the Ouled Nail in Algeria enjoyed the freedom to earn their own fortunes, choose lovers and engage in sexual relationships outside of marriage in a society that placed no shame on these choices – and indeed valued these activities as important contributions to the overall community.

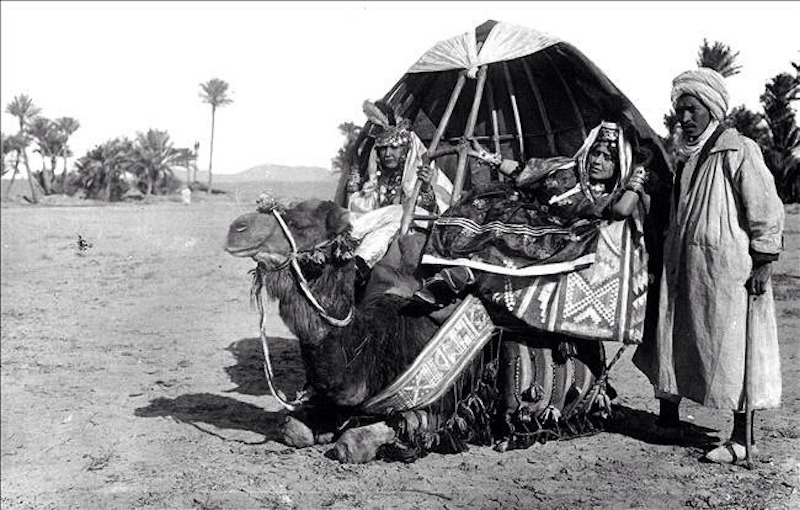

An Amazigh tribe, the Ouled Nail lived high in the Atlas Mountains. The nomads converted to Islam in the 7th century but maintained their unique culture, traditions and identity into the 20th century. Perhaps the most widely recognized of these traditions was that of the Nailiyat dancers.

Nailiyat women left their rural mountain abodes seasonally, descending into the larger cities and oasis towns to work as professional dancers and hostesses. Not all Nailiyat women were dancers, but the practice was usually passed down within families, where girls learned the dance and other skills from older relatives. While women from nearby tribes engaged in similar practices in times of economic hardship, such as upon being orphaned or widowed, it seems it was only the Ouled Nail who freely chose and proudly perpetuated the tradition by handing it down to their children, who began performing around the age of 12.

The men remained behind at home, so during their seasonal stays in the city the dancers formed strong women-centered communities in which the mothers, aunts and grandmothers played chaperone and kept house while the younger women performed and entertained. Men were invited into this cocoon as friends, business associates, lovers or clients, but their presence was temporary and somewhat peripheral. It was the women around whom this life was built and revolved, and it was the women who ordered it.

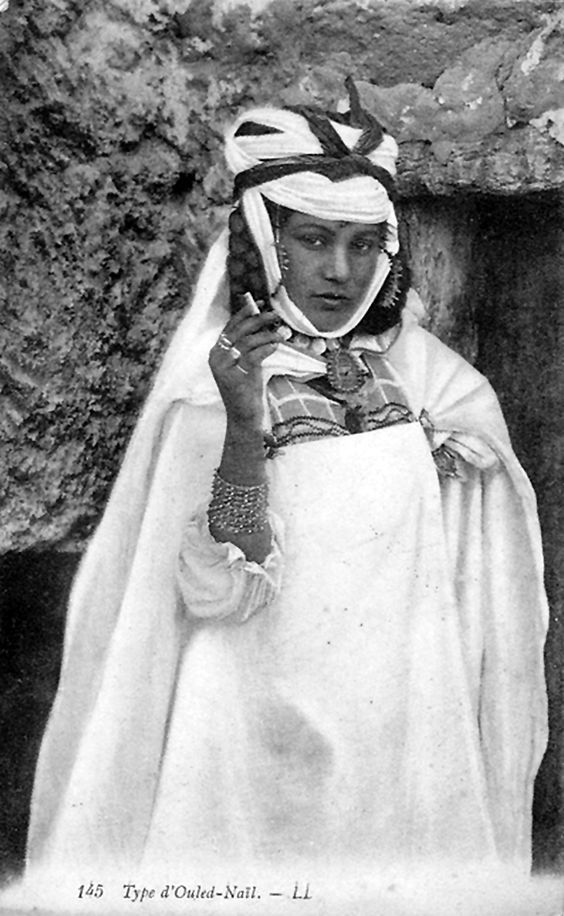

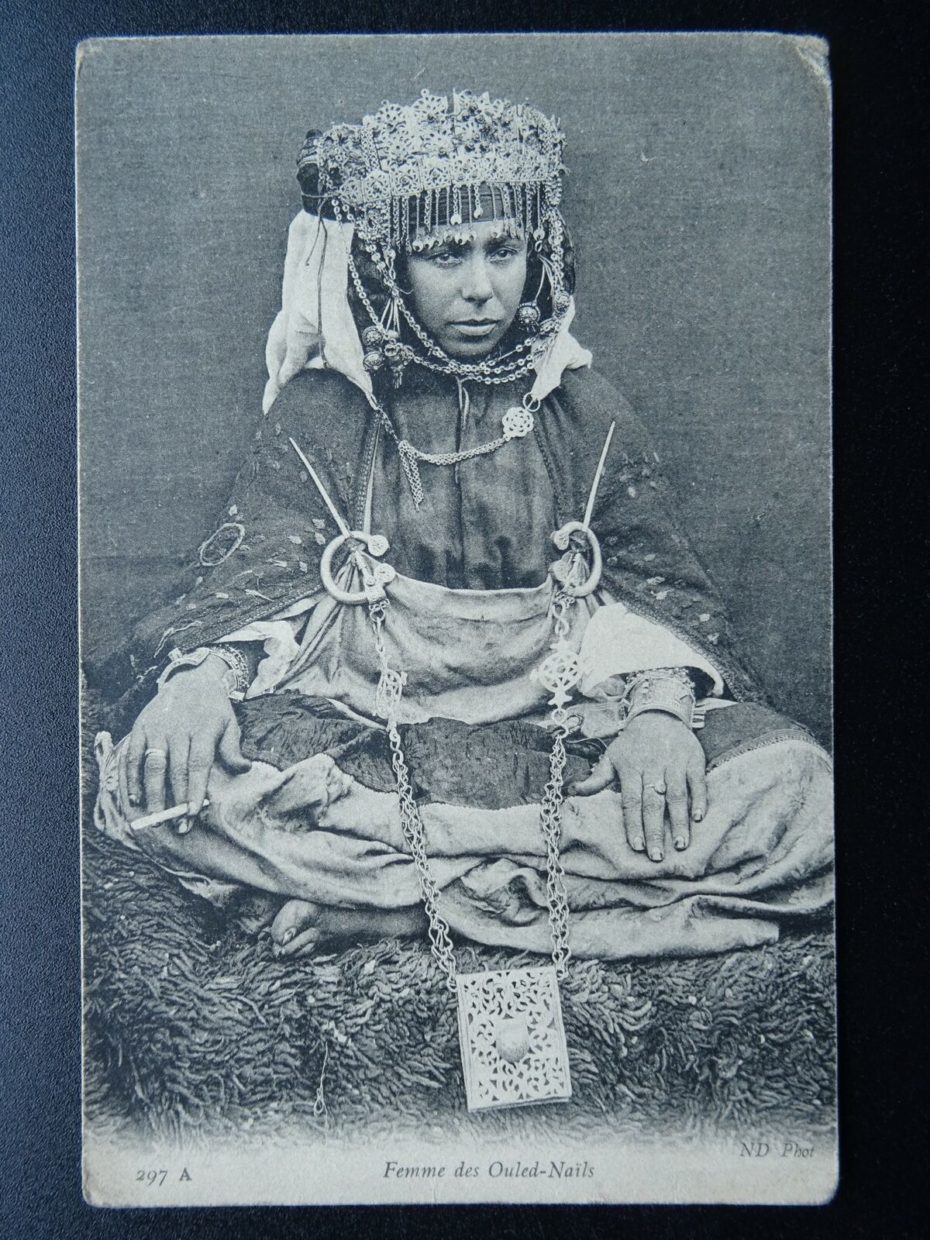

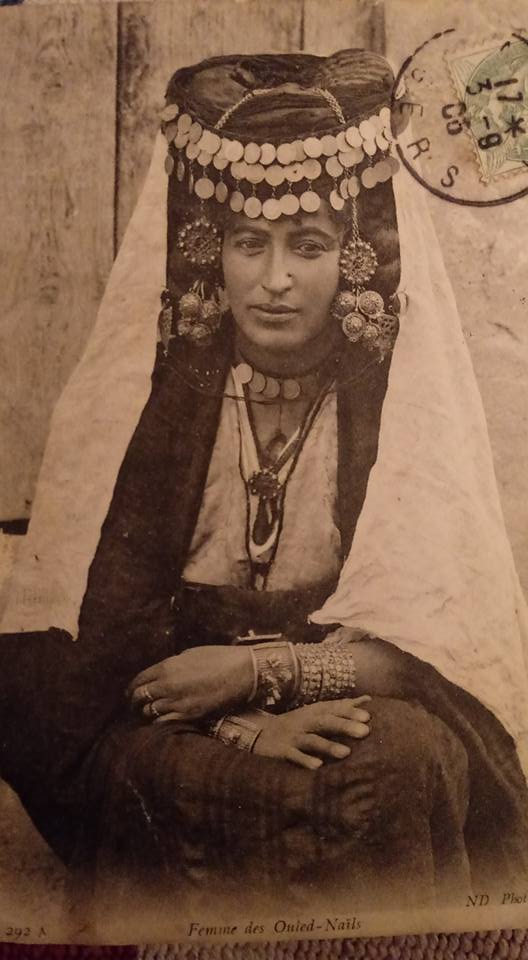

Dressed in lavish layers of silks and other opulent fabrics, the Nailiyat braided their hair into long, thick plaits, tattooed their faces with symbols of their tribe and decorated their hands and feet with henna. Elaborate gold and silver jewelry and headdresses made from coins earned in their trade advertised their success and desirability, and heavy bracelets fashioned with large spikes were said to serve as weapons for protection. While wearing one’s wealth may have ostensibly kept it in sight and safe, it also meant people with ill intentions knew exactly what they might stand to gain. Stories abound of Nailiyat being murdered for the jewelry they wore.

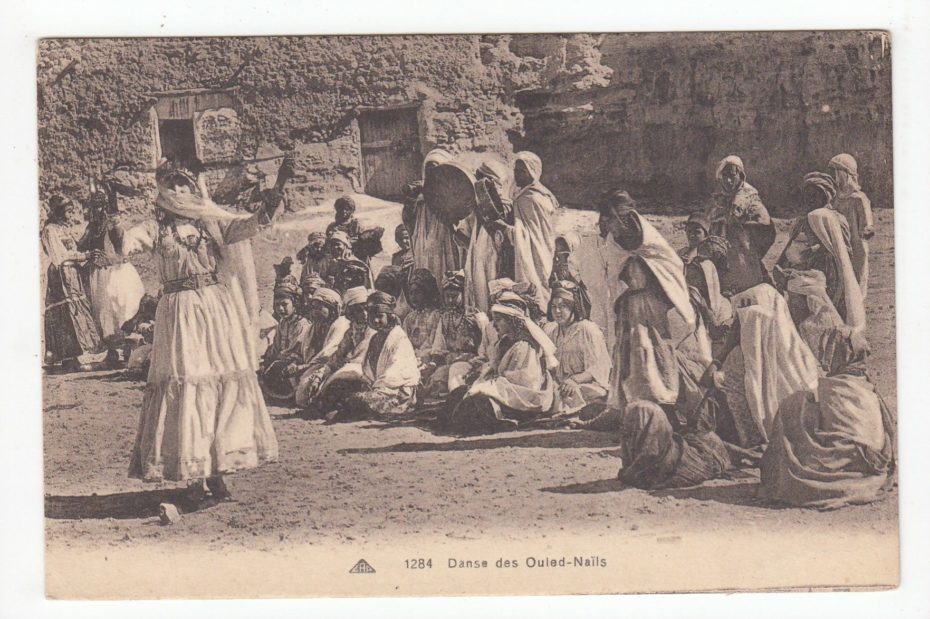

Groups of dancers performed together, with each one commanding center stage in turn while the others accompanied her with singing, chanting, clapping and snapping alongside the male musicians. A high-pitched ululation called a zaghareet announced the beginning of the performance. The dancer moved slowly, shuffling and gliding while rocking her pelvis rhythmically and accenting the rhythm with taps of the heel that caused her ankle bracelets to jingle. Head slides, shoulder shimmies and backbends all punctuated the dance. Some dancers exhibited amazing muscle control and athletic feats such as vibrating each breast individually. Turns and hand gestures may once have suggested a link between heaven and earth. Observers frequently commented on the gravity of their demeanor and their impassive facial expressions. These were women who understood their worth.

While they were famed among their people primarily as dancers, the Nailiyat also entertained men in their homes with the full support of their older relatives. The arrangement was something akin to patronage or even the modern-day escort system in which men understood they were expected to acknowledge the time, attention, hospitality and conversation extended to them with gifts that could be both material and monetary. That attention could certainly be laced with charm and sensuality, but it was up to the individual Nailiya to decide how far that attention might go. She was free to take on lovers, who would then provide support by showering her with even more gifts. But she did not accept a set fee for set acts, and she was under no obligation to accept the advances of any man who approached her. If she became pregnant, the child was welcomed and stayed with the mother. The birth of a girl was a particular cause for celebration.

After several seasons, once a Nailiya was satisfied with the wealth she had accumulated, she returned to her village where she would buy a home and establish herself as woman of independent means. She could then entertain suitors and settle down into married life for love rather than property or connections. The men of the Ouled Nail recognized a dancer’s professional experience as a positive attribute that contributed to her desirability as a wife.

In the 1956 book Flute of Sand, author Lawrence Morgan quotes one man as saying, “Our wives, knowing what love is, and having wealth of their own, will marry only the man they love. And, unlike the wives of other men, will remain faithful to death. Thanks be to Allah.”

Some dancers never left the business. Preferring city life, she might purchase her own cafe and mentor younger generations the way older women in her life nurtured her. In either case, her work would not have been toward a dowry to be handed over to her husband, nor was it a rite of passage she needed to endure in order to reach the goal on the other side. It was an occupation, a trade, a career and a tradition of which she and her people were proud.

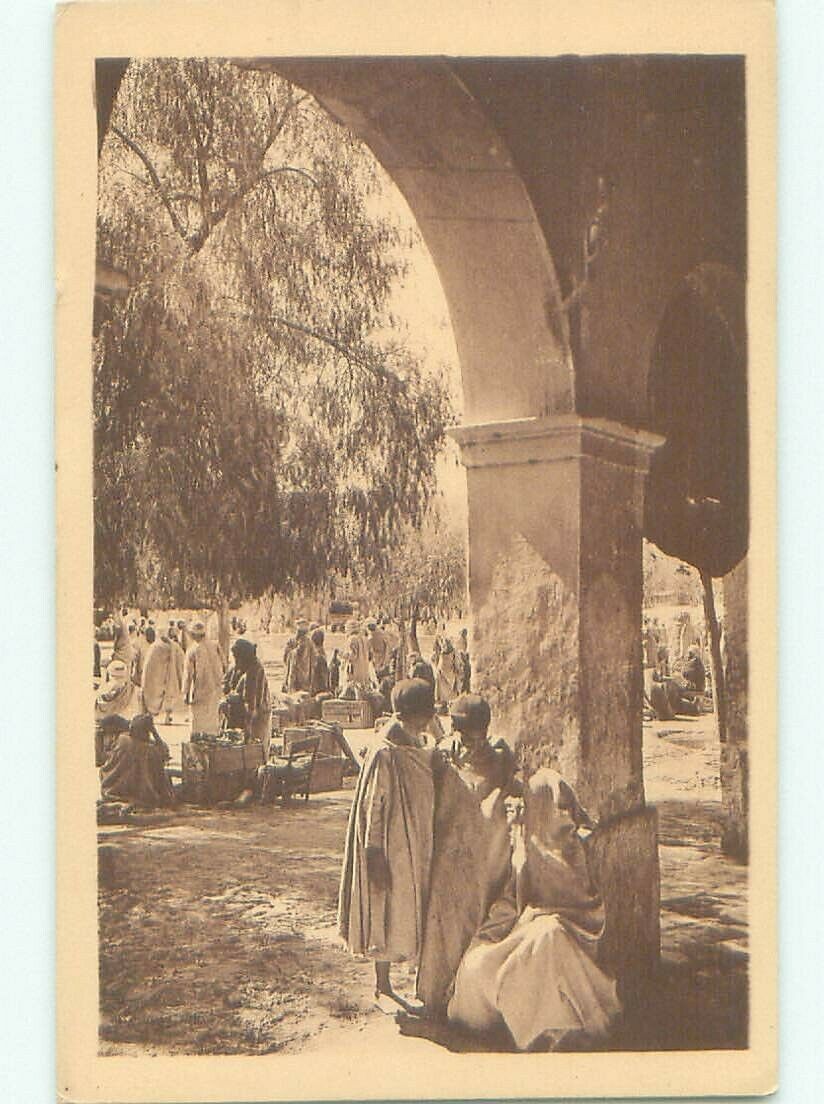

The Arabs were entranced by these dancers in their billowing gowns and glittering jewelry. In fact the name of Bou Saada, the city to which the Nailiyat are particularly connected, translates to “Place of Happiness” in Arabic, a fact attributed to their presence. With the French occupation beginning in 1830, Europeans also discovered the innumerable charms of the Ouled Nail, and suddenly salons on the Continent were awash with Orientalist paintings, and soon photographs and postcards, of beguiling women dripping in coins.

But colonial fascination is a double-edged sword: while we have an extensive and arguably beautiful photographic record of the Ouled Nail, that record came at the price of exploitation of the women pictured and the eventual destruction of the traditions these photographs purportedly preserved.

Instead of attempting to understand the complex dynamics of the place the Nailiyat held within their traditional society, the French immediately equated these artists with prostitutes who, in French society, were seen as low class, degraded and disposable. With the additional layer of an Orientalist view of non-white women as exotic, subhuman and depraved, the Ouled Nail suddenly found their movement restricted by arbitrary French government rules meant to reign in activities deemed morally corrupt, and at the same time, heavily taxed and fined to fuel the colonial machine. And yet the French continued to take advantage of the entertainments the Nailiyat offered as they eroded the foundations that supported them. With their activities relegated to specially licensed cafes run by the well-connected, they were deprived of the women-led collectives that ensured their safety. The women faced both exploitation and poverty as the money flowed upwards to the hands of foreign men.

The vintage postcards of the Ouled Nail we most commonly see today were products of this milieu. Algerian anthropologist and master dancer Amel Tafsout observed that most of these postcards, while presented as slice-of-life images, were staged and styled to appeal to the preconceived notions of the West, intentionally placing the Ouled Nail in opposition to “respectable” white women back home. The jewelry is layered on too thickly, the headdresses are piled too awkwardly high, the poses are distinctly welcoming to the foreign male gaze – exotic and erotic. We have intentionally chosen to omit the most overtly sexualized photos out of respect for their subjects, whose names we will never know and who may have been coerced in various ways to participate in these photoshoots. But cheap postcard racks of the late 19th and early 20th century were stacked with images of Ouled Nail completely or partially nude, in tableaux that no foreign photographer would have witnessed as part of the everyday lives of his subjects.

These were images created for voyeurs, and their appearance on postcards allowed European society to cheaply buy and trade in nameless Algerian bodies with little regard for how the practice affected either the individual women or their society. Photographers such as the notorious Rudolf Franz Lehnert and Ernst Heinrich Landrock trafficked in stereotypes, both creating and perpetuating Orientalist ideas about African women. Even the vaunted magazine National Geographic has a troubling history of presenting Black and Brown women in ways that would have been unthinkable for white women and which positioned them as objects to be consumed. The January 1914 issue was entirely dedicated to an article by Frank Edward Johnson titled, “Here and There in Northern Africa,” which included many of the photos of the Ouled Nail that eventually appeared on postcards.

By the time Algeria won its independence from the French in 1962, the lifestyle of the Ouled Nail had been irreparably ravaged through more than a century of colonial occupation and nearly a decade of war. The authoritarian government that took hold after independence forced a final phase of assimilation on nomadic peoples. Though the Nailiyat tradition has all but disappeared, the Ouled Nail as a people do still exist. Dance researcher Aisha Ali spent time embedded with remaining members of the tribe in the 70s, learning their dances and making live recordings of their music.

At a time when women in the East and West, the Global South and the Global North are defending their right to self determination in the face of powers who wish to control them, the Ouled Nail remind us that despite what some history textbooks may tell us, women have have existed outside patriarchal constructs and exercised their own choices on their own terms for centuries.