When German forces took Athens in April 1941, they expected to find thousands of centuries-old artifacts in the National Archaeological Museum, Greece’s largest museum. Instead, the neo-classical building was totally empty, besides the archaeologists and guardians still on duty. Officers asked them where the relics were hidden and “they answered enigmatically that antiquities are where everybody knows they are: under the ground.” Little did the Germans realise that the museum staff had literally buried all statues and artifacts underground in concrete fortified trenches right under their feet.

As with most concepts in German, it had its own word: Raubkunst, the plundering of art and other items by the Third Reich during World War II. While Nazis originally focused on the property of German Jews, as the Axis power’s geographic conquests expanded, they also targeted public and private collectors across Europe through the Reichsleiter Rosenberg Taskforce. While this might have been the greatest art heist in history — some 650,000 works — collectors around the world found unique ways to thwart the thefts. The 2014 movie The Monuments Men tells a somewhat true version of the real Allied troops tasked with saving artwork and culturally important items from the Nazis. Although less told are the stories of entire museums that were taken off walls and hidden, often within a matter of months. From Greece to France to Wales, here’s how three collections were preserved…

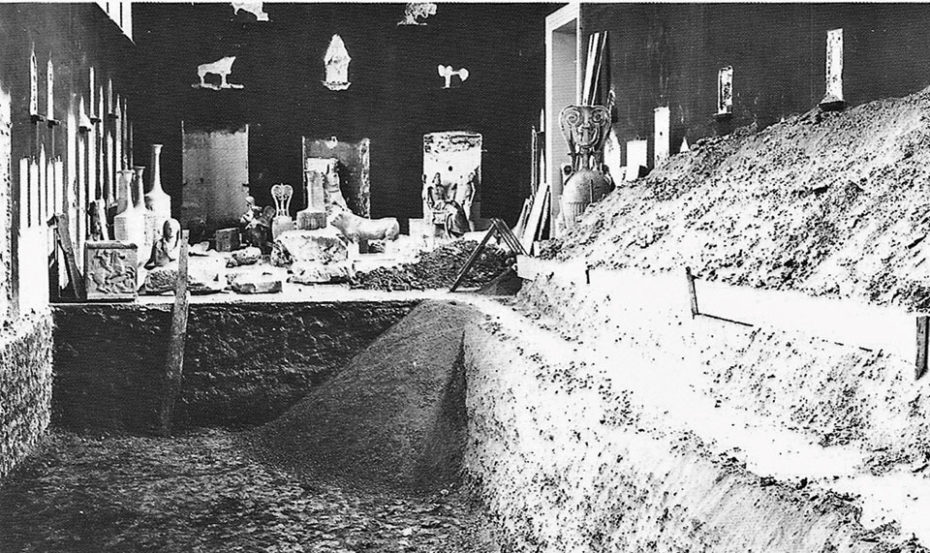

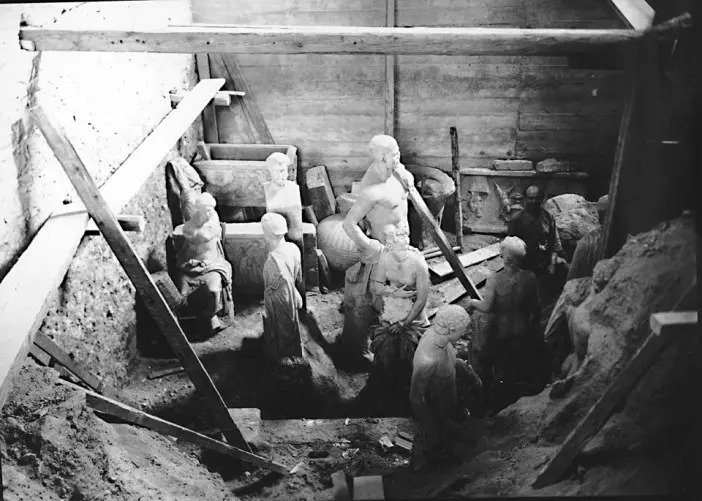

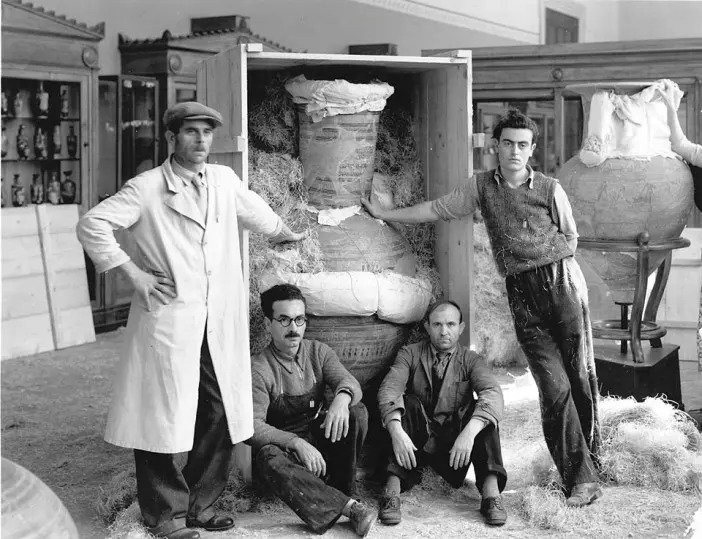

The plan for the Archaeological Museum in Athens was of course long in the works; after Greece’s entry into the conflict, the Ministry of Culture and museum officials worried how the country’s rich heritage could be protected from bombs. In 1940, the Committee of Hide and Secure was organised to develop storage spaces beneath the museum halls. Semni Karouzou, a curator at the time, described them as being “reminiscent of mass graves” and wrote about the operation in the museum’s archives. “Really early in the morning, even before the moon had set, the people who had undertaken this job would gather at the museum and they would leave for home really late at night.”

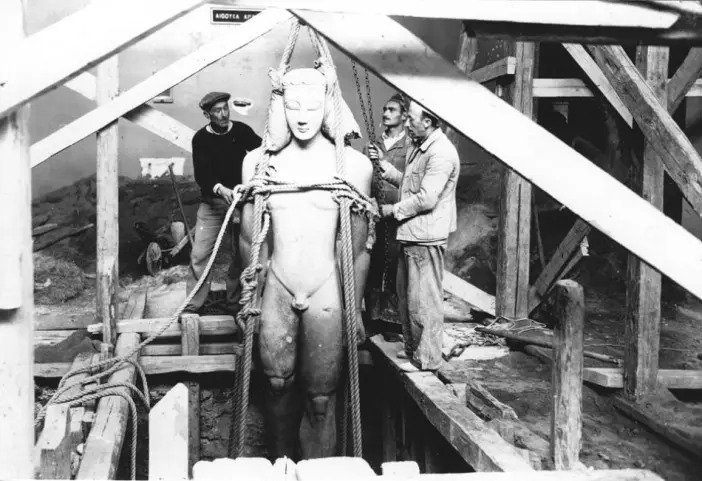

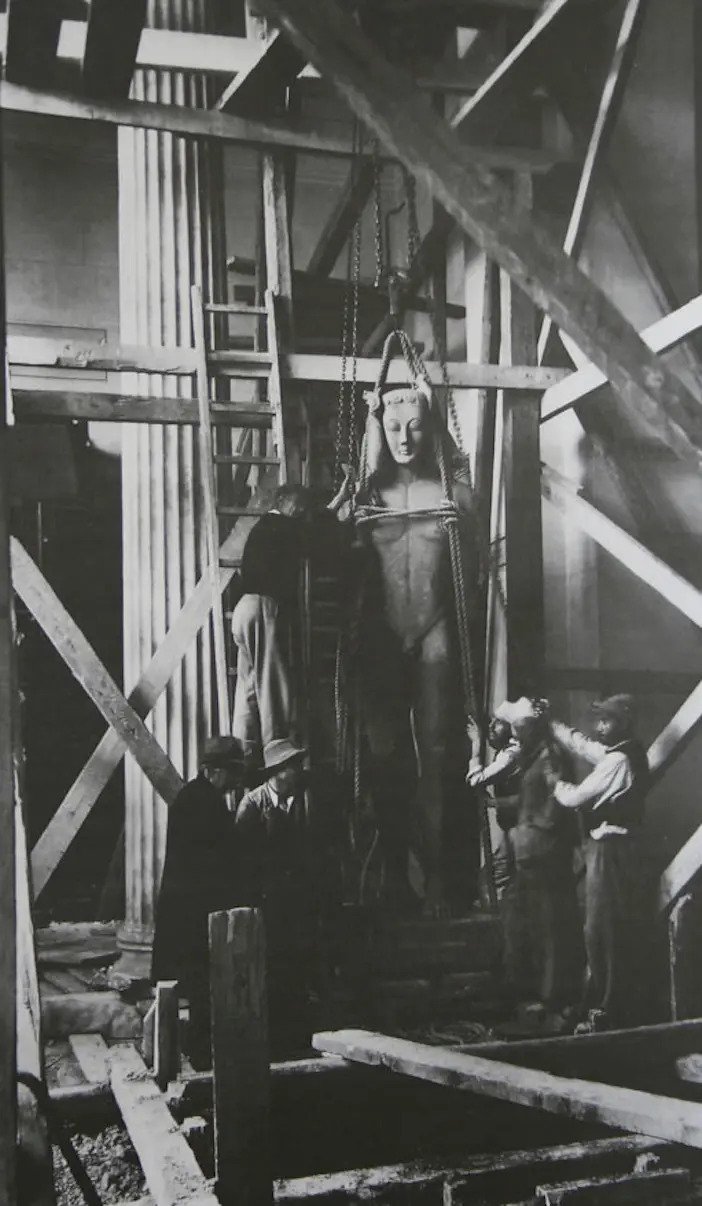

Improvised wooden cranes were used to safely lower larger statues. Smaller objects were stored in wooden boxes coated with tar or wax paper to alleviate the impacts of humidity in the trenches that stretched beyond the museum to surrounding streets in the bustling capital. The rooms where then filled with sand to minimize ruptures from bombs. The museum’s detailed catalogs that would reveal where everything was buried (as well as gold and valuable treasures from Mycenae) were stored by the Bank of Greece. In six months — just 10 days before the Nazi’s arrival — a whole museum had been packed away and buried. Of course, after the city’s 1944 liberation, carefully excavating and remounting the works was a process in and of itself.

In France, Jacques Jaujard, the director of the French Musées Nationaux, also anticipated the German occupation of his country. (Jaujard was not inexperienced: He had previously helped evacuate the Prado Museum in Madrid during the Spanish Civil War). On the 25th of August 1939, the Louvre Museum closed for three days — under the pretence of “repair work” — when in fact, some 203 vehicles transported 1,862 wooden crates filled with close to 4,000 works, largely to the famed Château de Chambord in the Loire Valley.

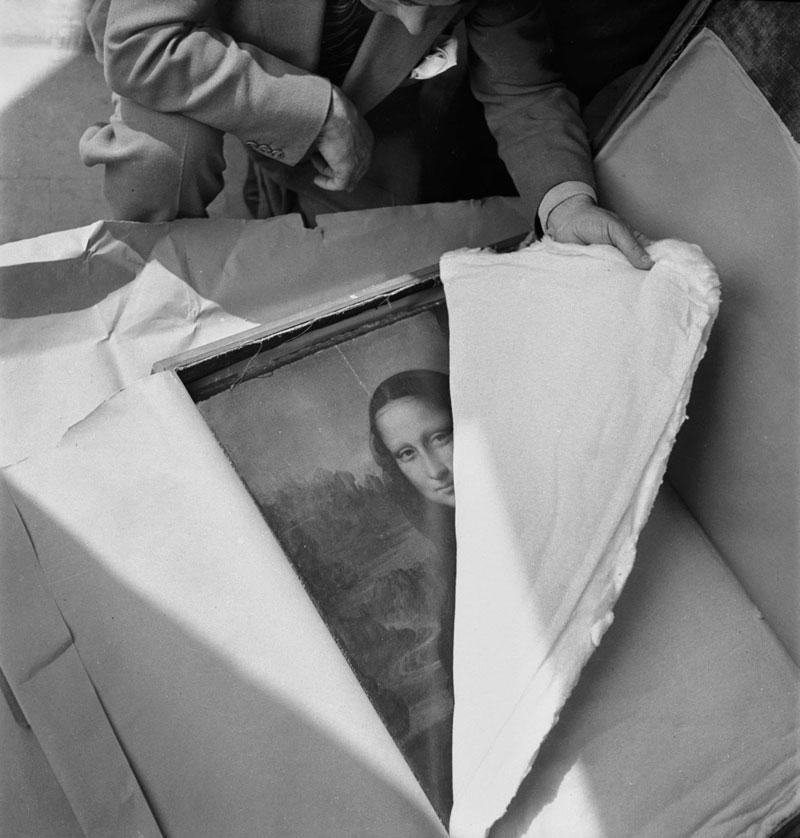

About 200 members of museum staff worked on the project with students and department store workers, some of whom would sleep in the museum during the evacuation. To keep the work anonymous, crates were marked with one to three (depending on a work’s importance) coloured dots to represent the value: green for major pieces, yellow for very valuable ones, and red for the world’s greatest treasures. The Mona Lisa received three red circles.

Large pieces like The Raft of the Medusa by French romantic painter Théodore Géricault were simply covered in blankets. The final piece to leave the Louvre — Winged Victory of Samothrace, a Hellenistic sculpture of Nike — was removed on the 3rd of September 1939, the day France declared war on Germany. But ferrying artwork out of the French capital and into the more calm provinces didn’t totally secure its safety. Famed pieces like the Venus de Milo and Mona Lisa traveled from castles to abbeys to museums. Guillaume Fonkenell, the curator of a 2009 Louvre exhibit on the war years, told the Associated Press that the Mona Lisa “was stored in a bedroom so that there would always be someone with her. There were people who slept with ‘Mona Lisa’ in their bedroom.”

Hoping to regain some sense of normalcy, the occupying German forces even reopened the Louvre in 1940, although most of the galleries in the palace were empty and the ornate gardens had been turned into vegetable plots. (Sadly, the museum was also used as a gathering place to package and send off art plundered from Jewish families and art dealers). Although, thanks to Jacques Jaujard, all of the masterpieces were returned after the liberation of France in 1945.

Across the Channel, Prime Minister Winston Churchill was adamant about not moving the United Kingdom’s art. When the National Gallery’s director, Kenneth Clark, suggested migrating the collection to Canada, Churchill responded: “Hide them in caves and cellars, but not one picture shall leave this island.” Plans to relocate the London museum’s collection were finalized back in 1938. In the 10 days leading to the British declaration of war on the same day as France, the National Gallery’s collection was largely sent to Wales. The works — including Leonardo Da Vinci, Rembrandt and Vincent Van Gogh paintings totalling in the millions of pounds — was scattered, from the University of Wales at Bangor to Penrhyn Castle to the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth.

While it was originally hoped that separating the art would keep it safe from air strikes, as fears of a German invasion intensified, the decision was made in 1940 to centralize the collection. As Phil Carradice wrote for the BBC, “It was, at best, a stopgap arrangement. The risk of a stray German bomb falling on Bangor or Aberystwyth was felt to be too great. And, besides, the owner of Penrhyn Castle was apparently often drunk – what he might do or say was not something that Kenneth Clark could easily contemplate.”

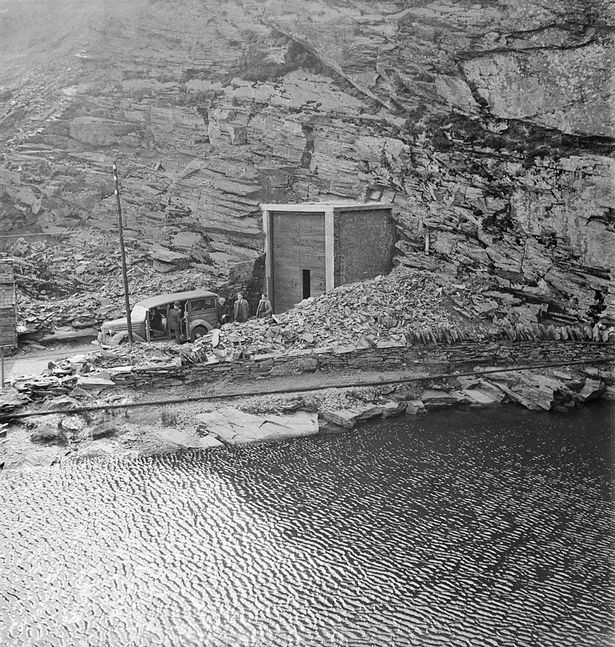

The solution? An unused slate quarry called Manod. Explosives were used to enlarge the entrance so bigger paintings could fit. But it wasn’t an easy transition: Lorries making the difficult journey on a single-lane road. To fit under a bridge, the truck carrying the collection’s largest piece — Anthony van Dyck’s Equestrian Portrait of Charles I — had to deflate its tires. Inside the mine, brick structures called “bungalows” were built to store approximately 2,000 pieces of art.

According to Suzanne Bosman, the National Gallery’s senior picture researcher, the trucks that transported the world’s most treasured paintings to the hills of Snowdonia through were in fact disguised as Post Office vans and Cadbury delivery trucks to avoid detection. Although it can’t be confirmed, the rumours were that Hitler sent spies to the area searching for the caves and artwork.

The Ministry of Works was in charge with properly housing the works; this lead to unexpected discoveries, such as the appropriate temperature for preserving art and realizing that dry cave air actually left the works in better condition. This was also the first time the National Gallery recorded a full catalogue of the collection. It was a smart decision too, given that the National Gallery building was hit nine times during the Blitz. To keep spirits raised, celebrated pianist Dame Myra Hess and friends played lunchtime concerts in the National Gallery (attracting some 750,000 people over six and a half years) and from 1942 onwards, a painting was added back once a month; this temporary “Picture of the Month” exhibition remains in place to this today. And now, you can visit Blaenau Ffestiniog, the historic mining town near Manod and still tour some of the quarries.

So there you have it, a few tips on how to bury an entire museum.