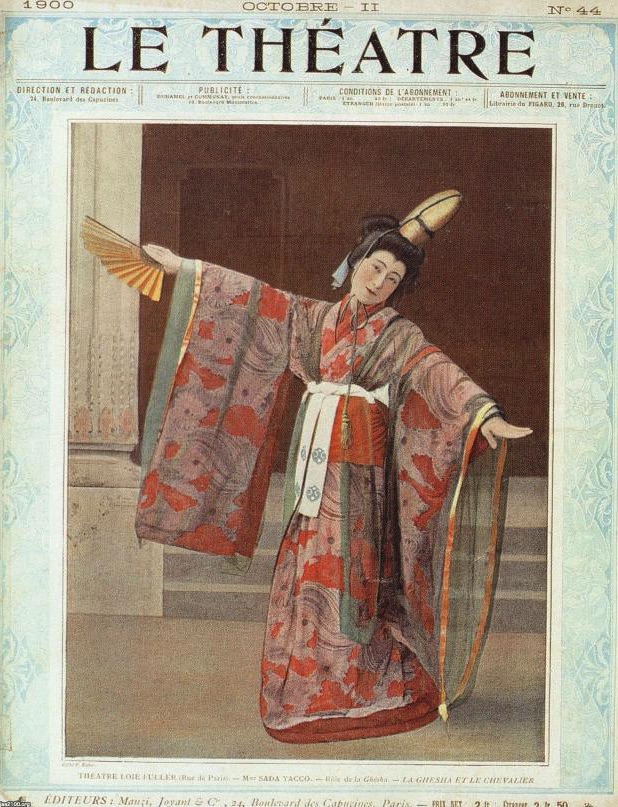

At the height of japonisme, Sada Yacco appeared like a comet, touring America and Europe with the first kabuki theatre company ever seen in the West. She was the undisputed star of the 1900 Paris Exposition, drawing bigger crowds and garnering more rhapsodic praise than the divine Sarah Bernhardt herself. A trailblazer who defied tradition as the only woman in an all-male kabuki company, she introduced Japanese theatre to the West and then brought Shakespeare to Japan.

Before she became Sada Yacco, she was Sada Koyama, born in the midst of the enormous social upheaval of the Meiji Era. Her father was a fudasashi, a middleman for the samurai. Under the feudal system, samurai were paid in bales of rice and relied upon the fudasashi to exchange rice for money and consumer goods. Around the time her parents married, Commodore Perry sailed into Edo Bay and forced Japan to open to the West. A civil war broke out, toppling the feudal system and three years later, Sada was born in 1871, the twelfth child in the family. By then, the samurai class had been eradicated and her family had lost their livelihood.

Sada later recounted bitterly, “When a son is born in Japan, there is great rejoicing and fetes, even among the poorest…. When a daughter comes, the feeling is different. She is despised and cursed and taught that in all things she is man’s slave and inferior.” At the age of four, Sada was sold to the Hamada geisha house to pay for her brother’s education. Three years later, her father died, and she was officially adopted by Kame Hamada, the proprietress of the Hamada geisha house. The great misfortune of her family turned out to have a silver lining. In the rigid patriarchal hierarchy of Japan, the daughter of a prosperous family would have been thrust into the background. Instead, Sada was groomed to take centre stage of Tokyo nightlife.

Her ambitious adopted mother spared no expense in Sada’s training. Sada received lessons in the traditional arts of flower arranging, shamisen, koto, and dance, but Hamada also encouraged her to “learn vulgar things just like a man.” Sada trained in jiu-jitsu, became an excellent horse rider, and excelled at billiards. More remarkably, at a time when most Japanese women were illiterate, she learned to read and write.

At the age of 15, Sada took the geisha name Yacco, and her virginity was sold to Ito Hirobumi, the first prime minister of Japan. With the patronage of one of the most important men in Japan, Yacco became the most sought-after geisha in Tokyo. Hirobomi released her from being his mistress after three years and her next logical step was to look for a husband who could offer financial security. But with numerous patrons and lovers, Yacco seemed to have no interest in settling down. But then she met the performer, Otojiro Kawakami.

He had caused a sensation with his satirical song that sounded like 1880s beatboxing, a scathing rap criticising the emptiness of the Japanese nouveau riche. He followed up this enormous success with a radical theatre style that was later dubbed shinpa (“new school”). The tabloids sneered at Yacco, a high-class geisha, for falling for Kawakami, a cocky hustler with a never-ending supply of big ideas. She paid no mind and dismissed her lovers and patrons. They were married in 1893 and Yacco formally resigned as a geisha.

Francois Coppée’s Pour la couronne (“For the Crown”), which premiered in Paris in 1895.

First, she helped Kawakami raise the funds to construct a Western-style theatre in Tokyo. It was a critical success, but they were mired in debt. Then he tried his hand at politics, which pushed them further into debt, forcing them to sell their theatre. Depressed and desperate to escape from financial woes, they bought a rickety boat, and decided to skip town. This strange adventure ended up as a tour of fishing villages from Tokyo to Kobe, with Kawakami regaling villagers with impromptu storytelling performances. The press had a field day reporting on the mad voyage, and when they eventually arrived in Kobe in January of 1899, there was a huge crowd cheering them on.

Among the crowd of admirers was Yumindo Kushibiki, who had opened a Japanese tea garden in Atlantic City. He proposed to sponsor and promote a tour of the United States from San Francisco all the way to his tea garden in Atlantic City. Sada’s husband leapt at the chance. They decided to present a repertory of traditional kabuki plays that would be timeless and universal, and quickly assembled a company. Three months later, they left Kobe for San Francisco.

“I intended to go only as Otojiro’s wife, to help out,” recalled Yacco. To her surprise, she discovered that Kushibiki had promoted her as the star of the company. Posters with her face were hung all over the city streets. An article in the San Francisco Chronicle proclaimed, “Madame Yacco, the Leading Geisha of Japan Coming Here.”

Kabuki theatre was actually founded by a woman, a temple dancer known as Izumo no Okuni, who began performing dances and comic sketches in 1603. During its first years, this new ribald street theatre was exclusively performed by prostitutes and women born into the working class. But after Okuni’s death, women were banned from the kabuki stage and forbidden to perform publicly until 1872. The restrictions against women performing with men were not lifted for another 20 years after that. Even today, most kabuki troupes are all-men.

In San Francisco, she combined her girlhood name Sada, with her geisha name Yacco, and made her professional stage debut as Sada Yacco. Though reviewers were somewhat mystified by such a different form of theatre, they unanimously marvelled at Sada Yacco. The San Francisco Examiner declared, “[T]he most celebrated geisha in Japan, adored by prime ministers, sumo heroes, and kabuki stars … could bewitch anyone – even a theatre full of Westerners who could not understand a word she said.”

The tour however, quickly turned into a disaster. Their sponsor, Kushibiki, had suffered a business loss and quickly abandoned the company. Thrown out on the street, they were forced to rely on the Japanese-American community to get back on their feet. They traveled to Seattle, Tacoma, and Portland, and then reached the nadir of their misfortune in Chicago where some of the actors pitched camp on the Chicago River. Finally, at the Lyric Theatre, they discovered that the daughter of the manager was an ardent collector of Japanese art who persuaded her father to offer the company one Saturday matinee performance. Fortunately, they had arrived in the United States in the midst of a craze for all things Japanese, which had begun with the opening of Japan in the 1850s. The matinee was packed and the performance was a resounding success, despite the fact that the cast was so weak from hunger that they could barely get up from jiu-jitsu throws. Sada Yacco nearly fainted during a series of spins.

When they arrived in Boston for a two-month engagement, they were a sensation and their shows were attended by all of Boston’s fashionable elite, including Sir Henry Irving and Ellen Terry, who were also performing in the city. Kawakami and Sada Yacco in turn went to see Irving and Terry’s production of The Merchant of Venice. Impressed, Kawakami dashed off a Japanese adaptation, with Sada Yacco playing the Portia role. This marked the first of a series of Shakespeare plays that Kawakami would adapt. Throughout their tour, both he and Sada Yacco continued to educate themselves about Western theatre. They later performed in in New York City and Washington, DC for President William McKinley. After a stopover in London, where they performed for the Prince of Wales, they arrived in Paris. They had been engaged by Loïe Fuller, famed for her Serpentine dances. A shrewd theatre manager, she proceeded to impose her vision of Japanese theatre on Kawakami. She insisted that a dramatisation of hara-kiri – a form of Japanese ritual suicide by disembowelment – be added to the end of every single piece in their repertoire. She pasted notices outside announcing, “Hara-Kiri scene today!” The theater was packed with Parisians cheering the gory scenes. Even Sada Yacco was forced to add a female hara-kiri at the end of her dance.

Sada Yacco and Kawakami were not immune from stereotyping. Ironically, though they were committed to modernizing Japanese theater, they were forced to play up to the desire in the West for a mythical Japan with dainty Oriental dolls and savage disembowelment rituals. They still were able to subvert preconceptions, with the New York Times admitting that Sada Yacco “shows plainly that a Japanese woman can love deeply, hate savagely, and then die quietly.”

by Alfredo Müller. Kyoto Institute of Technology.

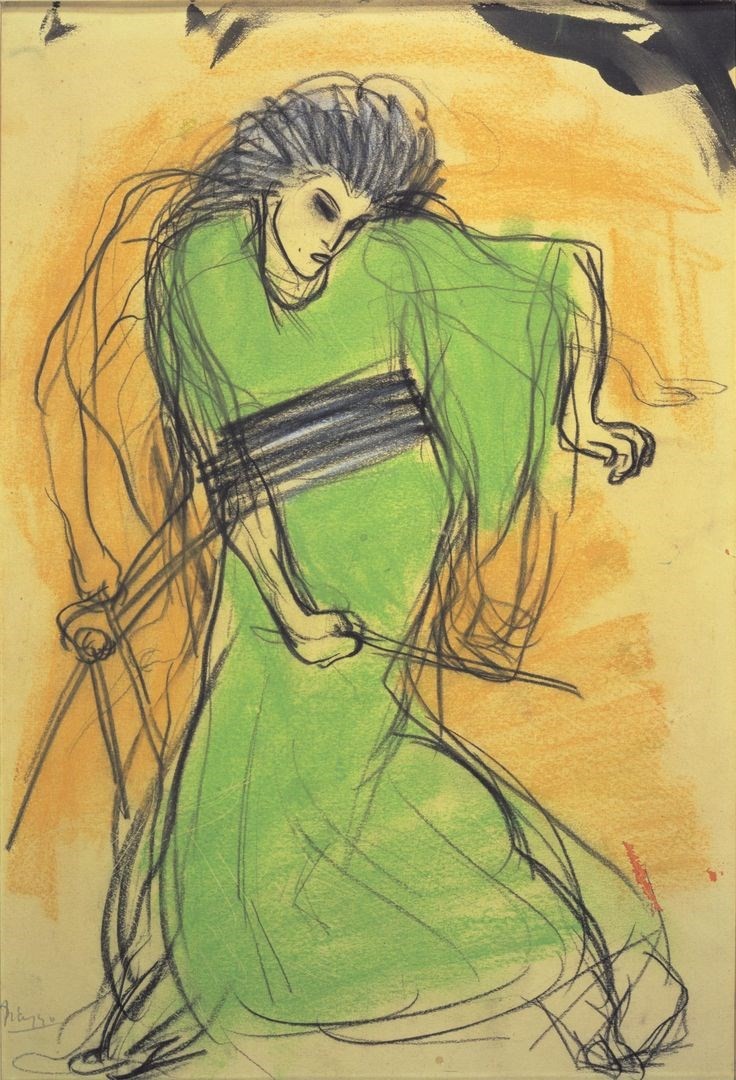

She was a triumph at the Paris Exposition. Andre Gide confessed that he saw her show six times and declared effusively, “In her rhythmic, measured passion, Sada Yacco gives us the sacred emotion of the great dramas of antiquity, which we seek and no longer find on our own stage.” She was so inspiring to Ruth St. Denis and Isadora Duncan, that she revolutionized modern dance. St. Denis later stated, “Her performances haunted me for years, and filled my soul with such a longing for the subtle and elusive in art that it became my chief ambition as an artist.” She was drawn by a young Pablo Picasso. Rodin wanted to sculpt her. She was on the cover of dozens of magazines.

Courtesy of Pieter CWM Dreesmann Collection

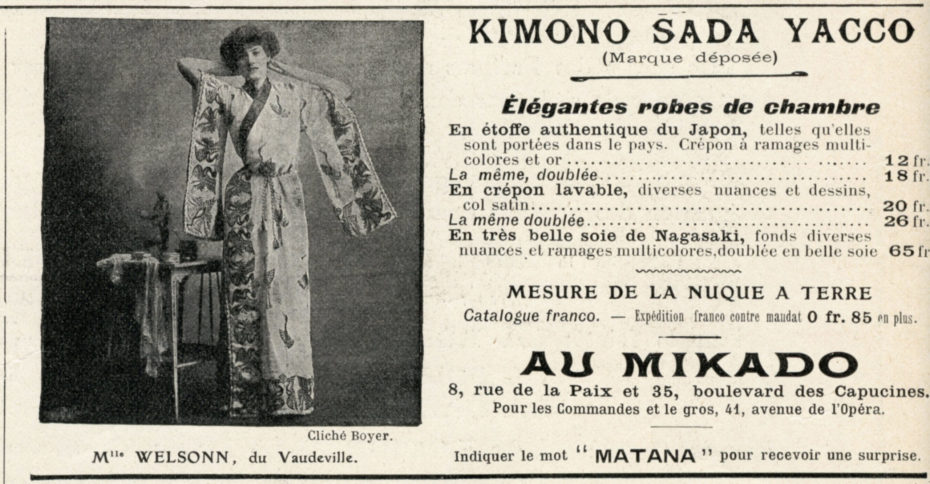

In France, Sada Yacco licensed the name “Yacco” as a brand name for a kimono, a face cream, and a perfume by Guerlain. In Russia, she dined with the ill-fated Tsar Nikolai II and marvelled at how men threw their overcoats on the ground before her to treasure the imprint of her foot. In Milan, their performances were attended by Giaccomo Puccini, who was writing Madame Butterfly. He incorporated a tune that he heard Sada Yacco play and cut out an entire act in admiration of the compactness of Kawakami’s adaptations.

After the triumph of their European tour, Sada Yacco and Kawakami returned to Japan and continued their experimental synthesis of East and West. Kawakami adapted Othello, Hamlet, The Three Sisters, La Dame Aux Camélias and Ibsen’s The Enemy of the People, all starring Sada Yacco.

Twenty years before Shakespeare in modern dress was ever attempted in England, Kawakami upset purists with a Hamlet who came onstage in a high school uniform riding a bicycle. The cultural transcriptions of classic plays that Kawakami practically invented are usual practices in today’s theatre.

In subsequent decades, Kawakami has been criticized for bowdlerizing kabuki and Western plays, but it was the first time that Japan and the West had ever encountered a theatrical tradition that was so vastly different. Kawakami and Sada Yacco helped bridge the divide, while also breaking new ground in theatre.

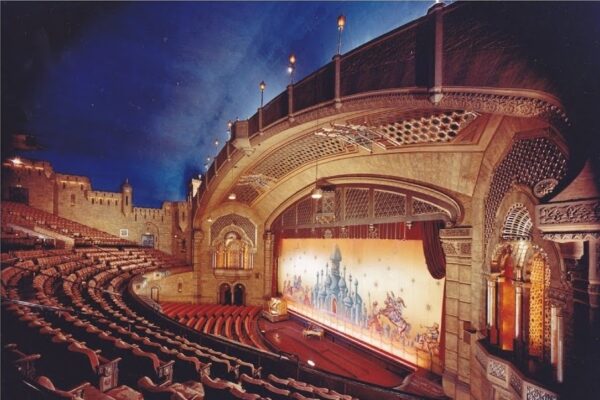

Sada Yacco and Kawakami traveled to Europe one last time in 1907. She studied at the Conservatoire de Paris and they presented several of their Japanese adaptations of Western plays. Upon returning to Japan, they built the Imperial Theater in Osaka. Sada Yacco also opened the first acting school for women in Japan, declaring, “I would like to train accomplished actresses, who might come to be called the Sarah Bernhardt’s of Japan.”

Courtesy of the Museu Nactional d’Art de Catalunya.

During World War II, Sada Yacco retreated to her villa in the seaside resort of Atami. She died in 1946 and was interred at Teishoji Temple. With Japan devastated by the war, there was scant coverage of the geisha who had captivated the West, but her legacy lives on in the generations of Japanese actresses that followed her.

About the Contributor