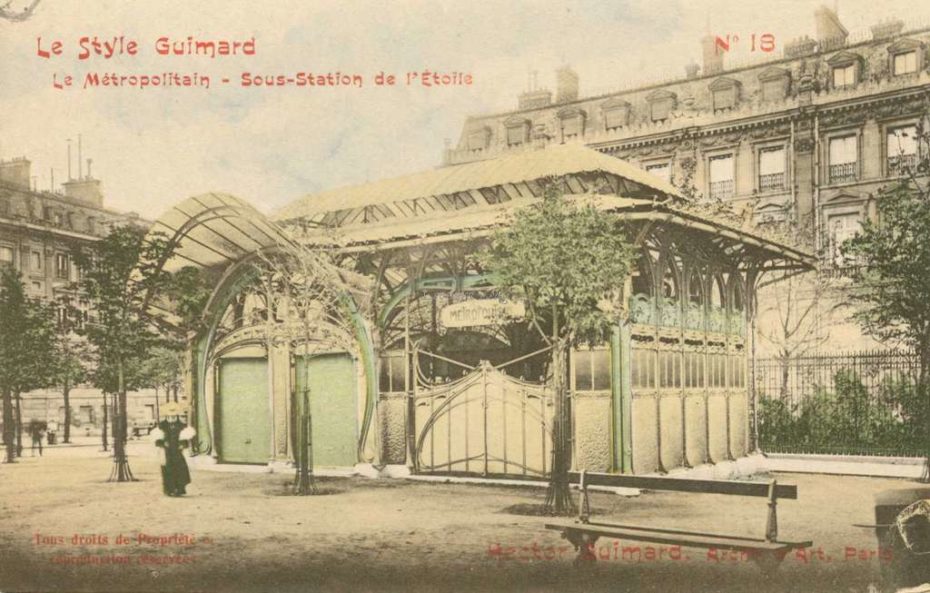

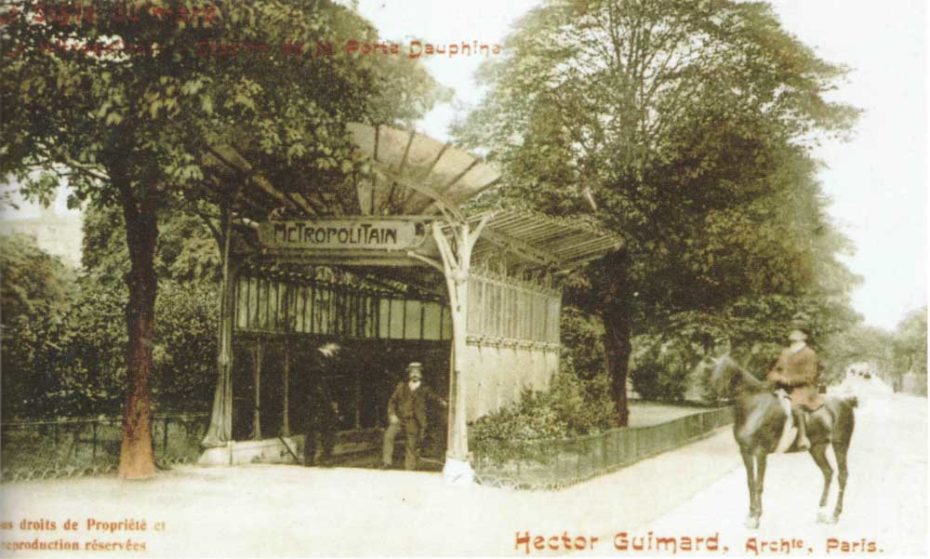

Paris is synonymous with the florid, tendril-like entrances that so eloquently frame one’s rabbit-hole descent into the belly of the Parisian metro, almost like a piece of theatre. The vibrant sage green cast-iron portals to the underground, often flanked by botanical stalks exhibiting the bulblike red lights overhead, are beacons that connect a modern metropolis to a time when Art Nouveau, in all its swirly curvaceousness, was flourishing. They are arguably the most memorable and distinctive relics from the Art Nouveau era – and some of the sole surviving heirlooms from the stables of the movement’s ephemeral wunderkind, architect Hector Guimard. His work defined the Parisian aesthetic, but by the time of his death in 1942, many of his buildings had already been demolished and only half of his iconic metro station gateways have endured to this day. It wasn’t until the 1970s that anybody set about saving what remained. His name should be as recognisable as Gaudi’s, but like so many of his fellow Art Nouveau pioneers whose legacy was sacrificed on the altar of pseudo-modernity, Hector Guimard’s fell into obscurity for too long. Let’s take stock of this often overlooked legacy…

Allow us to home in momentarily on Art Nouveau as a movement. The sad reality is that it was to be short-lived. At its conception the Art Nouveau movement had high hopes to be the 20th Century’s new direction for the arts and tried its damndest to escape the rigid nationalistic and ornamental shackles of the past. It steadfastly embarked on what it perceived to be a noble (albeit somewhat unchartered) course, with the sole aim of celebrating a fresh new aesthetic that was purely based on natural form and shape. Architects and artists from the late 19th century had been searching for a new way of doing things (as we’ve seen in the English Arts and Crafts Movement, Impressionism and the likes) and the Art Nouveau movement (1890 -1910) turned out to be one of the last of these movements. (Art Deco was in fact the last, literally at the very end of the road of the ‘Aesthetic Movement’.) Ironically though, whilst each movement had perceived itself as a new dawn, in truth they all were based on tradition and appropriation, copying form and iconography from the Middle Ages back to ancient Rome, Greece and Egypt. Perhaps the inherent flaw of the Art Nouveau movement was that, like its predecessors, it was naive in believing it could escape tradition.

To continue our saga, in stepped architect Hector Guimard. He was born in Lyon in 1867 and turned out to be an exceptionally gifted student at the École Nationale Des Arts Décoratifs, winning a staggering amount of accolades, medals and prestigious awards, which in turn, propelled him towards the École Nationale Des Beaux-Arts, the foremost architecture school in the world at the time, with all its establishment traditions based on historic European precedent.

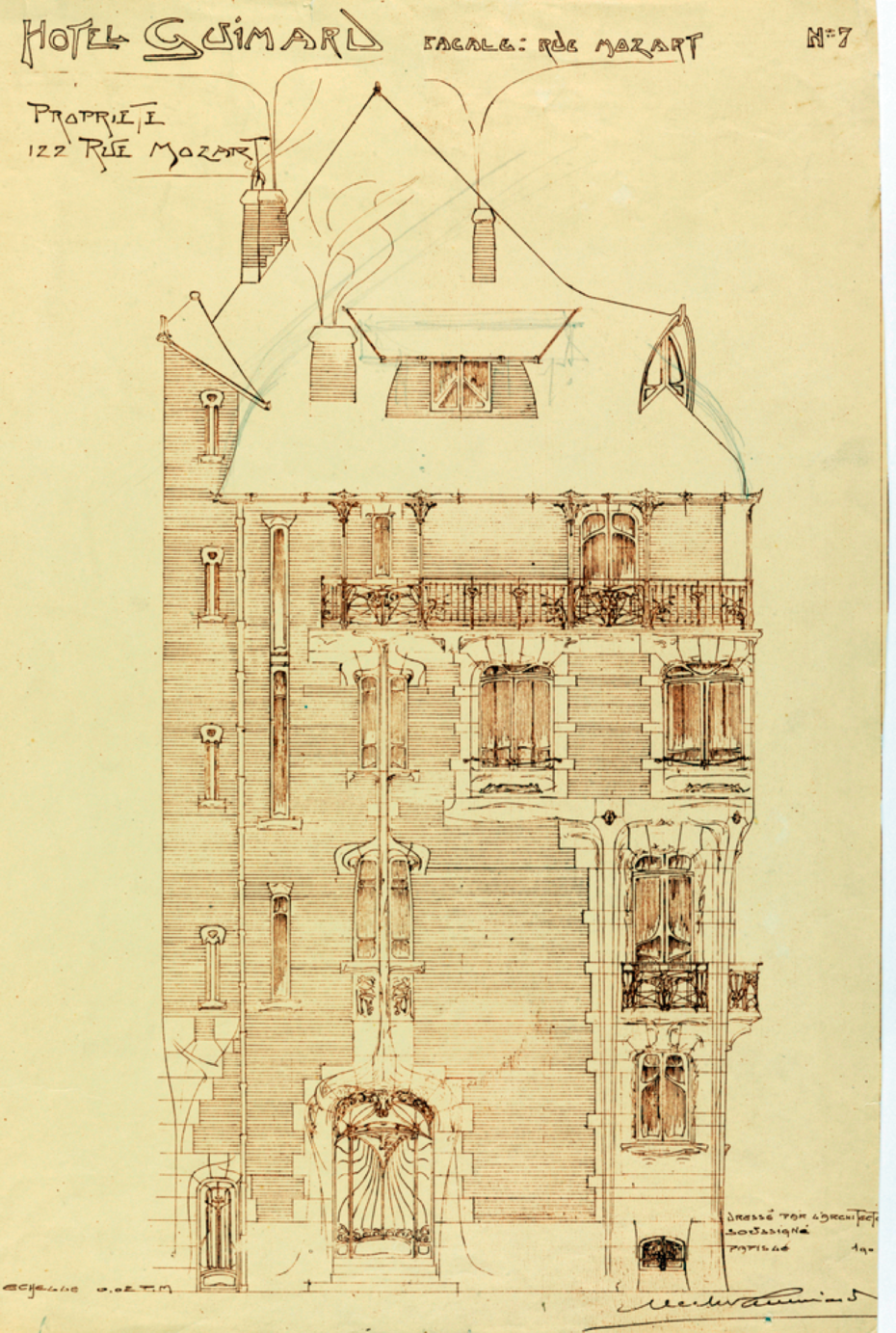

By the early 1890s Guimard’s career flourished through residential commissions, predominantly private houses and apartment blocks in the new 16th arrondissement of Paris, which was rapidly becoming an expensive and fashionable suburban area. One such apartment block was Guimard’s structurally traditional Castel Béranger (1895-98).

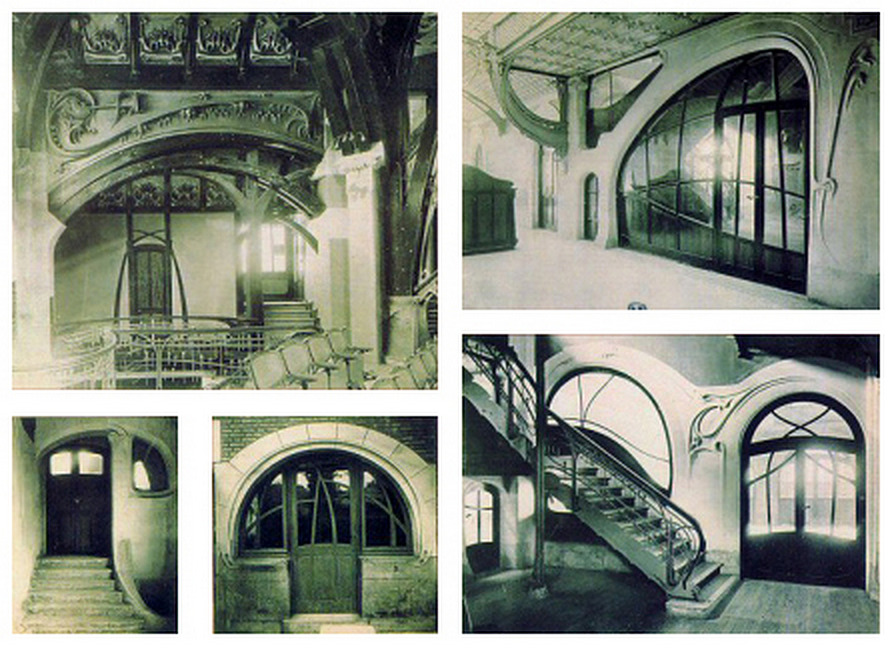

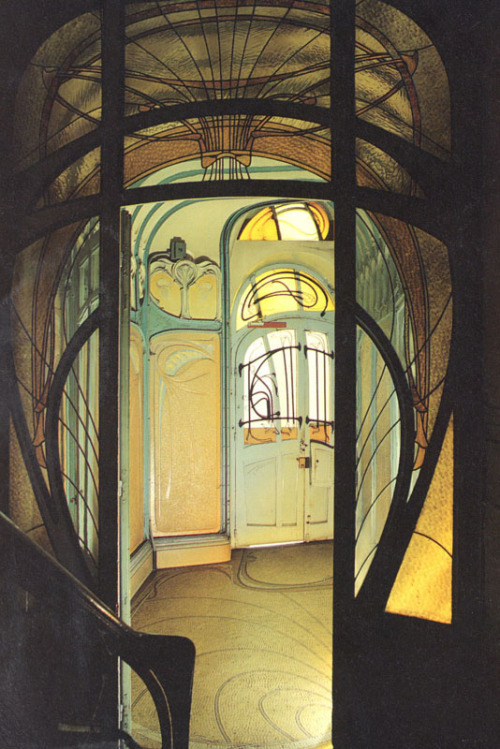

At the time, there was growing criticism of the identical facades of the buildings along the Paris boulevards built during the Second Empire by Haussmann, and in 1898 the City organised a competition for the most beautiful and original new building facades. Castel Béranger won that competition. Its undulating outside walls, as well as the lavishly decorated interior public halls, were adorned with Guimard’s unique Art Nouveau elements: the twisting metal railings, sinuous window bars and curvaceous stone carvings. All of these iconic features were yet to be seen in mainstream Paris and Castel Béranger would become the city’s first residence in Paris built in the style known as Art Nouveau and effectively launched Guimard’s commercial career. Located at 14 rue de la Fontaine, it is one of the few Parisian buildings by Guimard still standing.

His architectural output was prolific over a period of ten years. From the iconic to the lesser-known works, here’s a snapshot of a pursuit that sadly lasted only about a decade:

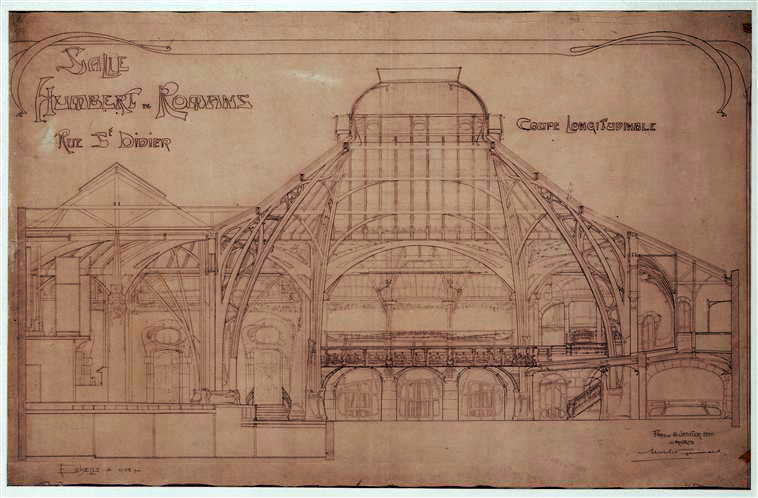

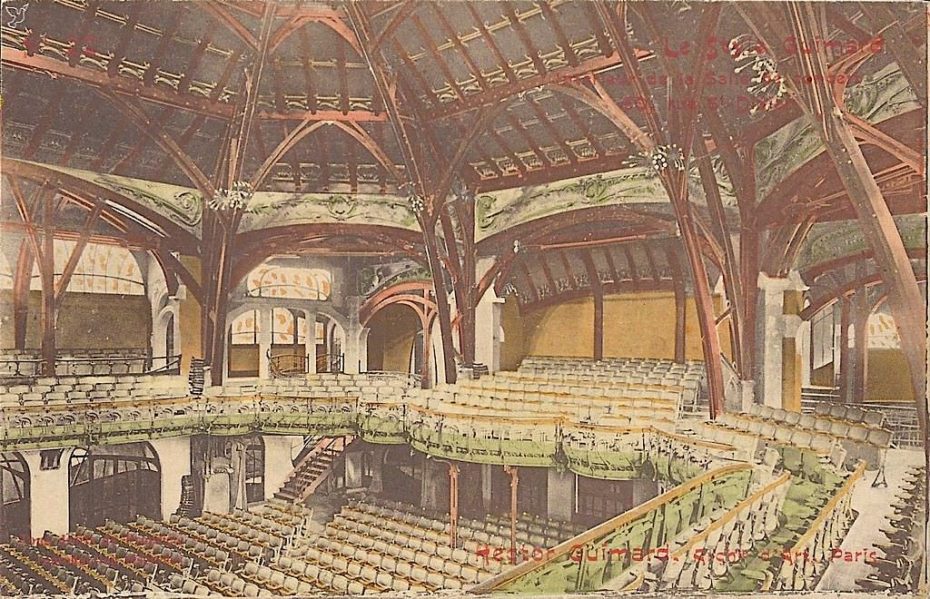

The Salle Humbert de Romans (1898 – 1901), is a public auditorium and whilst an outstanding architectural tour de force showing the pure Art Nouveau curvaceous expression of the interior ironwork structure and nature-based form, it was ironically doomed from the start. It stood for barely 5 years, it was a commercial failure and in the process of trying to catch the public’s attention by creating a public profile for the building, the very opposite was achieved – it was regarded as vulgar.

The Maison Coilliot (1900) in Lille is an Art Nouveau shop with three apartments overhead. It was built for a ceramics manufacturer who intended to use it as publicity piece. It brilliantly exploits Art Nouveau’s natural forms, its undulating shapes, its contrasts of solid and void and the joyful, vibrant colours. Today it stands as a dramatic contrast in amongst its dull and conventional neighbours.

The Castel Henriette (1899 – 1900) in Sèvres was a country house where Guimard developed a more modernist approach, in that the same materials were used both inside and out. Skinny, bendy and mechanical-looking, the flamboyant architectural composition also reworked many traditional medieval building elements such as towers and galleries.

In 1903 the look-out tower had to be removed, having been structurally unstable and by the 1930s the building was abandoned. It had a brief renaissance as an unusual 1960s film set for three or four French films before its eventual demolition in 1969. Perhaps too bespoke or untried, the fate of this building, like many other great buildings, may have been due to their inability to be adapted to have a contemporary use.

As Guimard’s popularity diminished in the early years of the 20th century, he was supported largely by one wealthy client, Léon Nozal, and his friends, who commissioned holiday homes, including La Surprise, a villa at Cabourg that was destroyed by the 1950s.

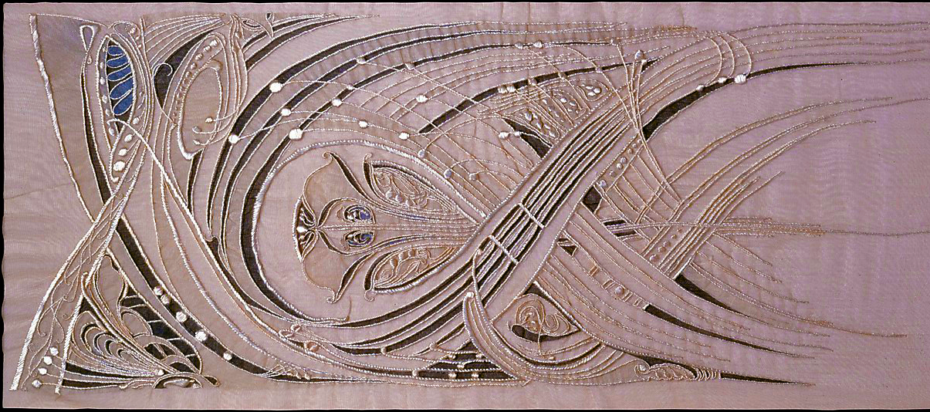

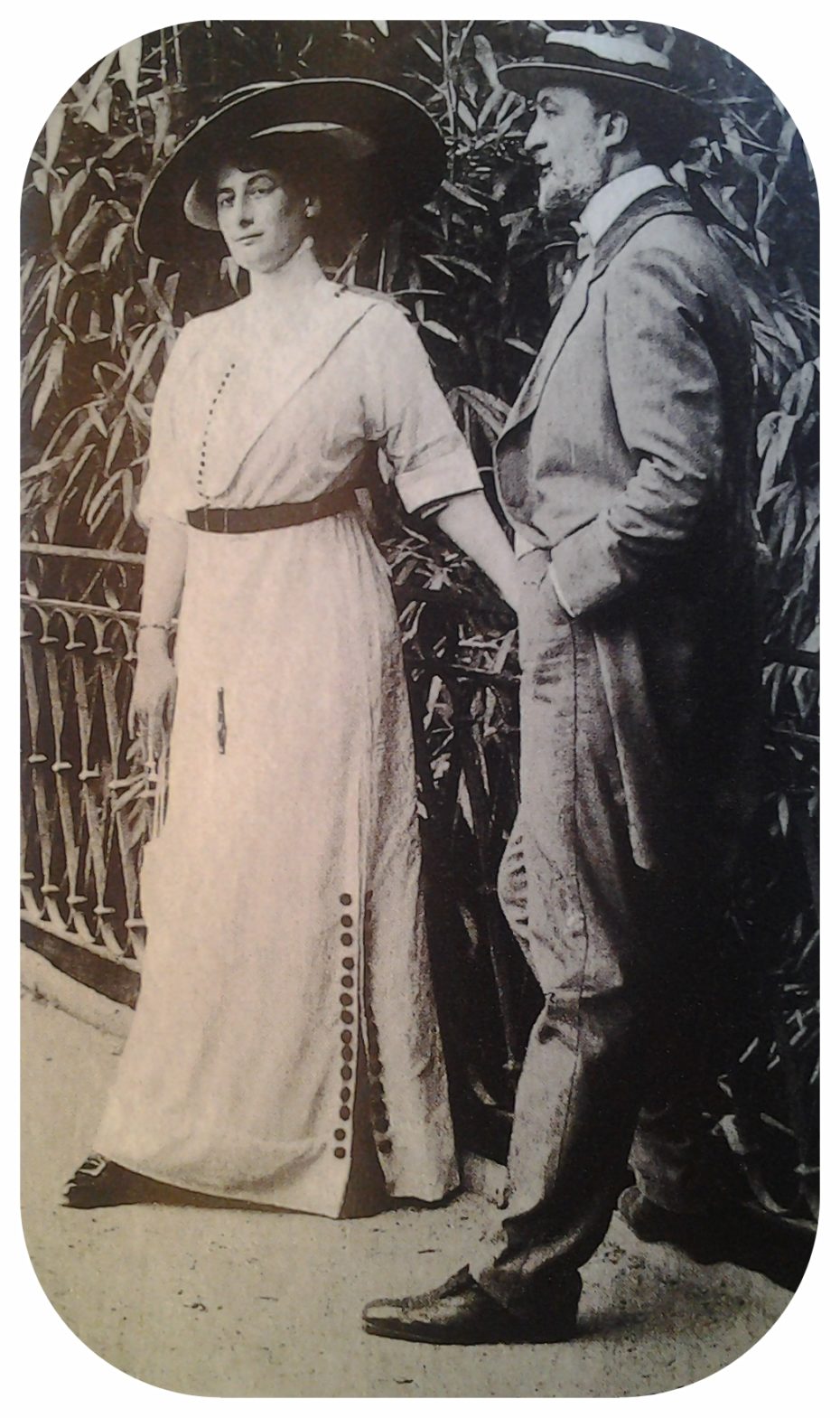

He was not known for designing many personal accessories, but during a particularly happy period in his life, he designed textiles, jewellery and clothing for his wife, who wore a dress designed by her husband for their wedding.

Perhaps the best known of all Guimard’s creations were the Paris Metro Entrances (1900 – 1913). Guimard was responsible for the first generation of entrances to the underground stations of the Paris Métro. A total of 167 were constructed. The cast iron columns and panels with florid glass roofs, sprouting otherworldly alien lighting fixtures, in many ways can be seen as precursors of contemporary industrial production and design. Unfortunately, like many later industrial age works, they were easily removed as stations were updated, seen as only dressing for the essential transportation function below.

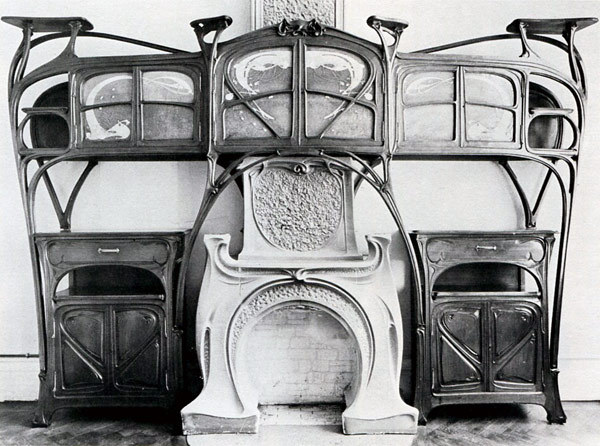

From twisted street walls to dramatically curved railings, from random window patterns to mannered compositions of eclectic architectural elements, from sensuously curved cabinetry to an exclusive set of graphics, Guimard was personally driven to create works in this distinctive new style that he championed. Often choosing to work in isolation, Guimard built up a robust practice through reputation and publicity.

At the dawn of a new century and in the spirit of a new age, Guimard became a very public social activist. It’s human nature to look to a new, brighter future at the start of a new era and some saw Art Nouveau as that future. Guimard in particular was deeply concerned with the European arms race. He became a vocal advocate for international peace relations, proposing disarmament. Needless to say, his pleas fell on deaf ears. And those who pinned their hopes on Art Nouveau were also sorely disappointed.

Curiously the Art Nouveau style never entered the mainstream, it remained niche, providing an alternative architectural and art expression, an eye-catcher for new commercial ventures. It’s also perceived as a rather ‘vulgar’ nouveau riche display and sometimes as a symbol of the anti-establishment nationalistic movements, as seen in the works of Mackintosh in Scotland, Gaudi in Catalonia and Horta in Belgium. Art Nouveau as a product, whether building, furniture or art, was heavily craft-dependent, with very few artisans trained in the expression of the craft at that time and was therefore very labour-intensive, expensive and exclusive. WW1 would bring radical social change, the ‘emerging’ common man could never afford Art Nouveau, which was seen as yesterday’s elitist fashion.

Art Nouveau was tarnished with the brush of two horrendous world wars and unfortunately, its key French proponent, Guimard and his body of work were regarded as neither useful nor relevant in the scheme of things.

In 1909 Guimard had married Adeline Oppenheim, a wealthy American Jewish heiress and painter who worked in Paris. Initially the couple lived in Paris at the Hôtel Guimard, but during World War I they left Paris to live in the far southwest of France, well away from the political and cultural heartland, and as Jewish discrimination loomed in Europe before the outbreak of WWII, they left France in 1937 to settle in New York, where Guimard died in 1942. One may speculate his architectural commissions had declined due to a cocktail of factors: a change in fashion, changing politics and change in his own lifestyle. Adeline Guimard worked tirelessly after her husband’s death to preserve his legacy and made generous donations of furniture and textiles to several American museums.

Had Guimard perhaps taken a wrong turn by basing his ideas for a new architectural expression on an elite and niche market? The new world of the 20th Century would demand simplicity, economy and function and were unimpressed with historic references or allegiances.

Art Deco, a more mechanical, geometric style flourished in the interwar years as it was much more easily applied to repetitive and rational, rectangular buildings. World War II would in turn see this style disappear and replaced by a truly functional aesthetic, based on simple, undecorated building construction. The pre-World War II historic styles and their associated sad memories were to be forgotten and erased. Progress was associated with the new, in the arts, architecture and technologies.

Sadly it seems Art Nouveau had opted for an ill-fated route, a cul-de-sac that lead nowhere. Today, what remains of Guimard’s work is thankfully revered once again and preserved as the products of a brief moment of misplaced but flowering artistic expression. Now almost unrepeatable, these relics have become iconic snippets of a zeitgeist that represented an imagined world.