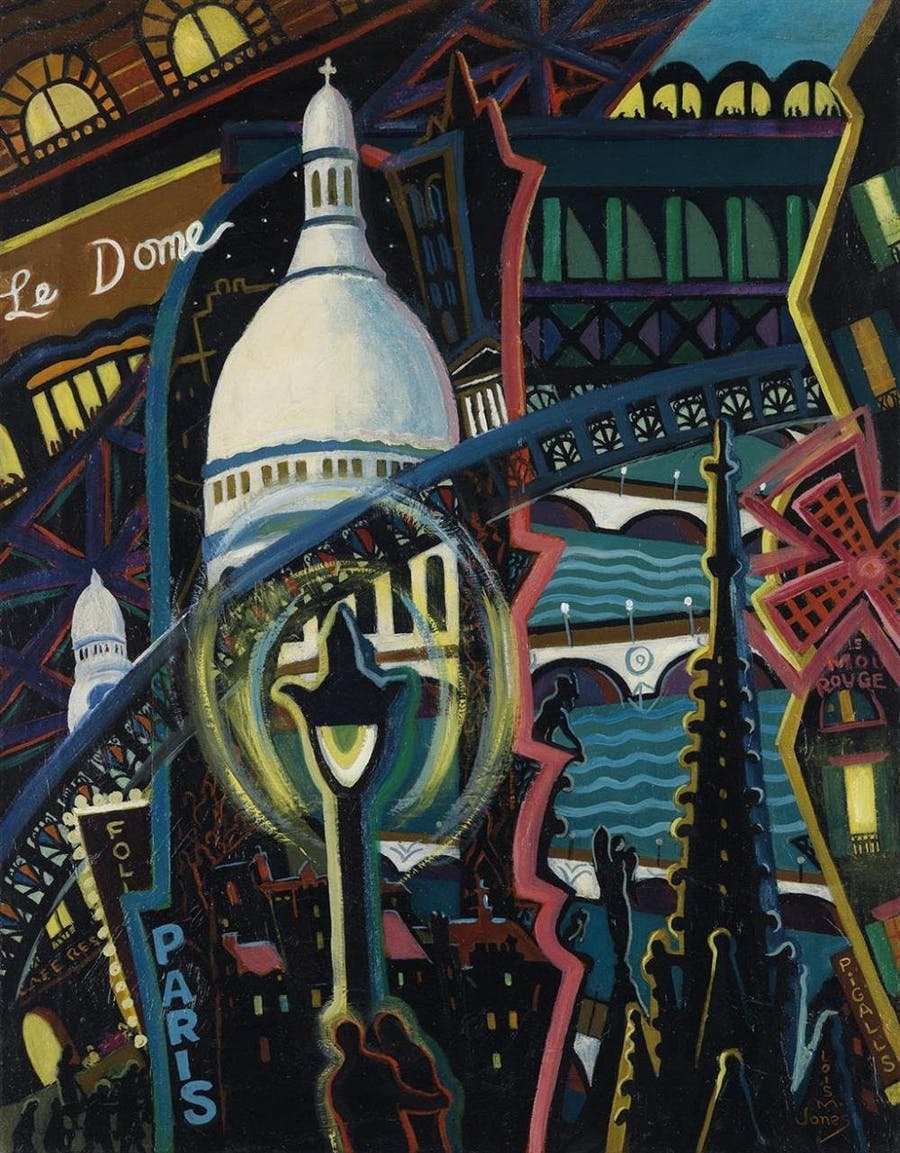

After the Great War, a new kind of music began to waft through the winding streets of lower Montmartre. Unrestrained, audacious, with a potent syncopated rhythm unlike anything ever heard in Europe. It was the music of Black Americans who had started to move into the neighborhood. For a brief time, far away from Jim Crow in the United States, they established a cultural utopia with no color lines. And for that brief interlude known as Les Années Folles, Montmartre became known as Harlem-on-the-Seine.

It all started with bandleader James Reese Europe during World War I. As lieutenant of the first Black infantry regiment, popularly known as the Harlem Hellfighters, his orders were to put together the best military band in the world. He convinced forty musicians to enlist, including notable composers Noble Sissle and Rafael Hernández Marín. The United States, however, was “uncomfortable” with Black men killing white men, even if they were German. After much debate, the Harlem Hellfighters were assigned to the French Army. The Harlem Hellfighters spent 191 days in the trenches, suffered more casualties than any other U.S. regiment, and caused a frenzy every time they marched through a French village playing ragtime jazz. Some of the Harlem Hellfighters headed to Paris after the war. Some of them returned home and experienced the 1919 race riots before hightailing it back to France.

Slap-bang jazz percussionist Louis Mitchell had played with James Reese Europe in New York City before he left for London in 1914. When Mitchell arrived in Paris in 1918 and bust out a drum solo, his sound was met with confusion and shock. Hardly anyone in Paris had ever heard jazz music, much less imagined any such thing as a drum solo. In fact, a trap drum or drum kit – with snare, bass, toms, high hat, and cymbals, arranged so one man could play them all – had never been seen before. He was promptly dubbed the “King of Noise,” but the new music was so sensational that he was soon engaged to lead the house band at the Casino de Paris.

By 1919, a craze for le tumulte noir was sweeping Paris. Desperate for an escape after so many years of death and deprivation during the Great War, Parisians turned to jazz, so refreshingly non-European, and so different, new and ecstatic. Black musicians were so highly in demand that it didn’t even matter how good they were. An ex-Harlem Hellfighter trumpeter wrote a friend, “Man, you should haul over here lickerty-split, they got flowing wine, willing women & no hassling of the colored man. In fact, they ain’t color blind—they’re color-crazy!”

Mitchell rented an apartment just up the street from the Casino de Paris, at the foot of Montmartre. He and his wife opened their house to Black people coming through Paris after the war. Many of them ended up living nearby. A tight knit Black neighbourhood started to form.

In 1919, one of the veterans who showed up at Mitchell’s door was Eugene Bullard. As a teenager, Bullard had run away from Georgia and stowed away on a ship to Europe. He became a prizefighter and toured with a Black vaudeville troupe, which led him to Paris just a few weeks before Franz Ferdinand was shot, ultimately leading to the outbreak of WWI. Bullard enlisted in the French Foreign Legion and was decorated with the Croix de Guerre for bravery in the trenches of Verdun. Then, at a time when Black men were still not allowed to fly for the U.S. Army, he managed to get assigned to the Lafayette Flying Corps (a name given to the American volunteer pilots who flew in the French Air Force) and became the first Black combat pilot.

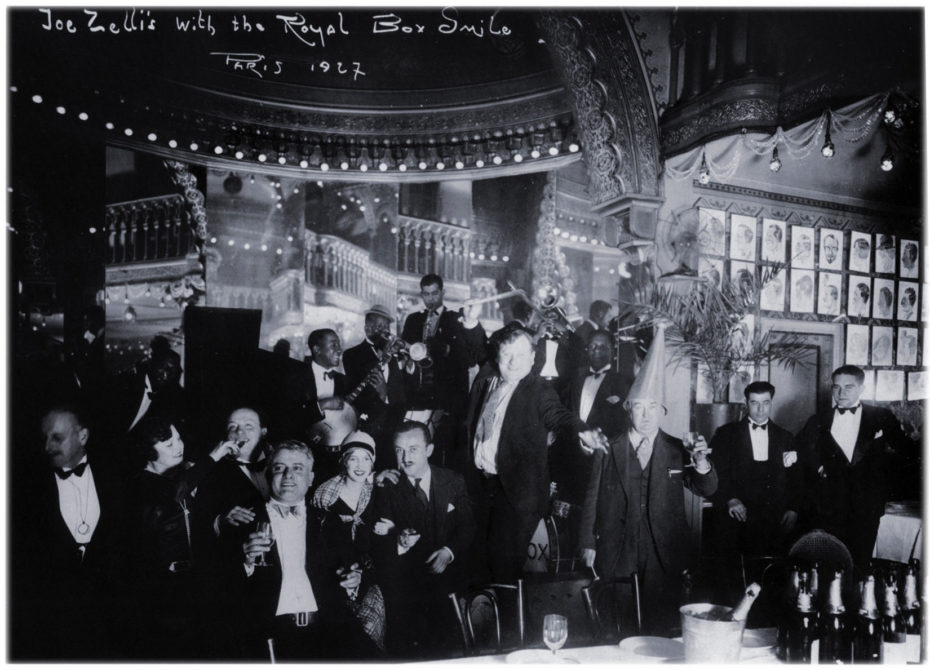

Arriving in Paris after the war, Bullard learned of the massive demand for Black musicians. He took drumming lessons from Mitchell and was soon proficient enough to find a regular gig at a nightclub. There, he met Joe Zelli, an Italian-American who had emerged in Paris after the Armistice. Zelli learned that a nightclub could be open after midnight if it served alcohol by the bottle instead of by the glass. Bullard, as a hero of the Great War, had a lot of connections and managed to find a lawyer to grease the wheels on a bottle club license. In return, Bullard got a steady job leading the house band and booking talent. Open from midnight to dawn, Zelli’s Royal Box was an instant success, drawing celebrities like Charlie Chaplin, Louise Brooks, and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

By 1924, Bullard was the proprietor of his own club, Le Grand Duc, which became the heart of the Black American community. Musicians gathered for after-hour jams, people came for news from America and down-home cooking. The house band included jazz drummer Buddy Gilmore and Arthur “Dooley” Wilson, who later became better known as Sam, the piano playing friend of Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca. The hostess of Le Grand Duc was Florence Embry, an American jazz singer and dancer who Langston Hughes would describe as a “petite, lovely brown vision, the reigning queen of Montmartre after midnight”. Her husband, the great pianist Palmer Jones, would tickle the ivories as she sang and sashayed through the small bar.

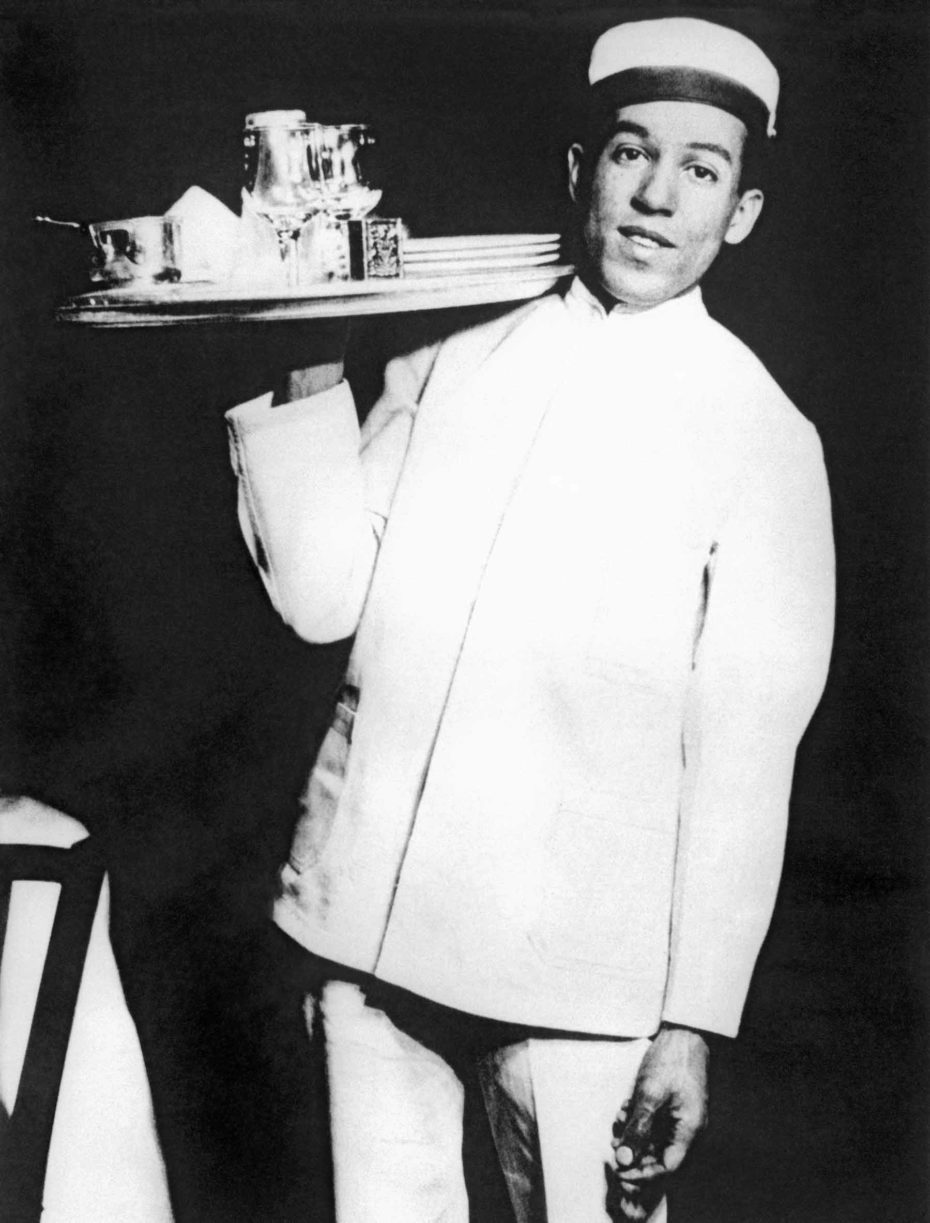

Langston Hughes had arrived in Paris after tramping around the world as a steamer sailor. He spent six months in Paris as a busboy and dishwasher at Le Grand Duc.

“When all the other clubs were closed, the best of the musicians and entertainers from various other smart places would often drop into the Grand Duc, and there’d be a jam session until seven or eight in the morning – only in 1924 they had no name for it. The cream of the Negro musicians then in France… would weave out music that would almost make your heart stand still at dawn in a paris night club in the rue Pigalle, when most of the guests were gone and you were washing the last pots and pans in a two-by-four kitchen… Blues in the Pigalle, Black and laughing, heartbreaking blues in the Paris dawn.”

-Langston Hughes

When Louis Mitchell opened a club across the street, he lured Embry away from Le Grand Duc. This left Bullard in quandary. He needed to find another hostess, but in 1924, there were few Black women entertainers in Paris. A friend suggested that he write Ada “Bricktop” Smith, who had been making a splash in Harlem.

(Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture)

Bricktop was a light-skinned Black woman with brick red hair and a personality as big as her heart. When she first stepped through the door of Le Grand Duc and took a look around, she burst into tears. She’d been a headliner at Connie’s Inn, a swanky ballroom with big Broadway-style revues, and now she was in a club just big enough to squeeze in twelve tables. Langston Hughes gave her some napkins to dry her eyes, brought her some chicken and dumplings, and talked her into staying.

(Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture)

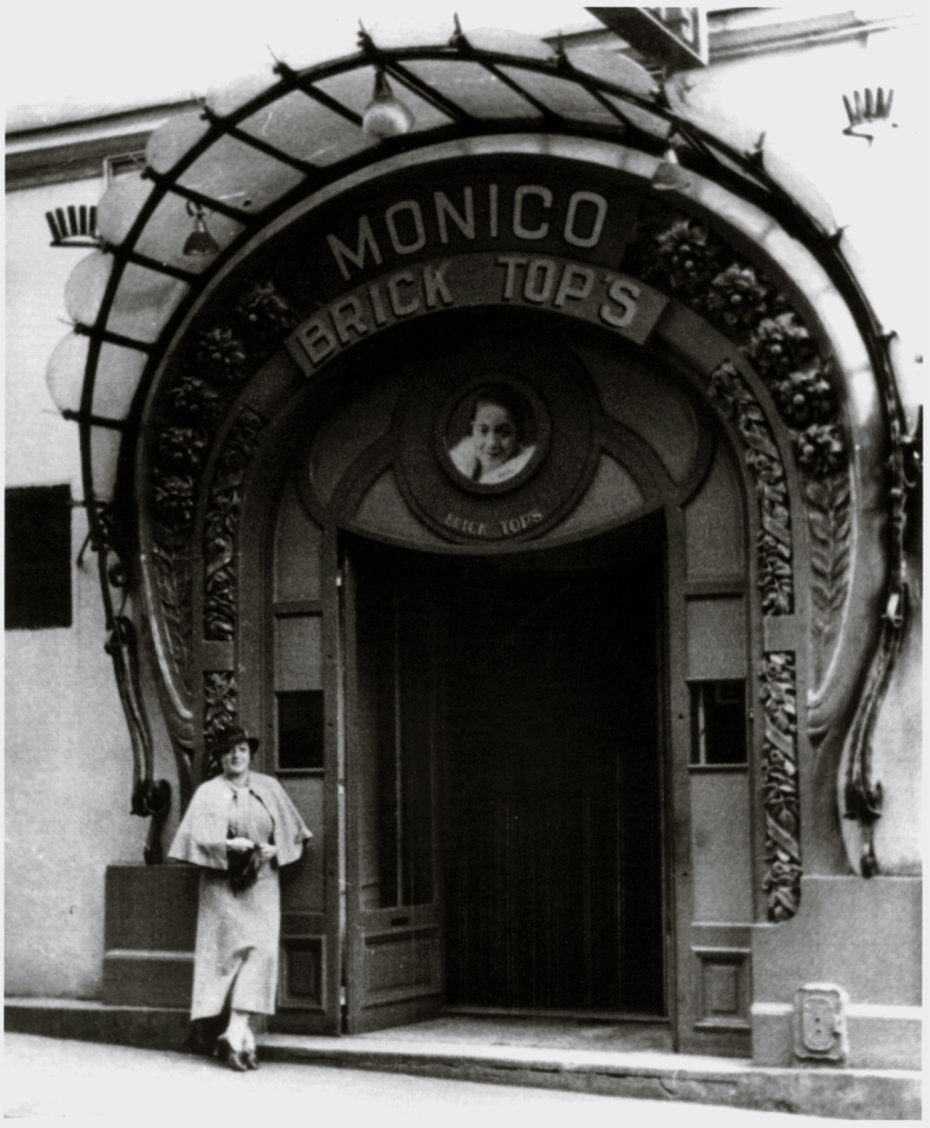

It wasn’t long before Bricktop was the toast of Paris. She ruled the roost at Le Grand Duc for five years, before opening her own establishment across the street. Whenever Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, or Fats Waller came to town, they played at Bricktop’s. Cole Porter became a good friend and wrote “Miss Otis Regrets” for her to sing. John Steinbeck was once kicked out of her club for being drunk and disorderly. He sent a cab full of roses in apologies. She taught the Charleston to Elsa Maxwell, the Prince of Wales, and Aga Khan III. Renowned for her dance ability, she once claimed, “Every time I shimmy, a skinny woman loses her man.”

(Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture)

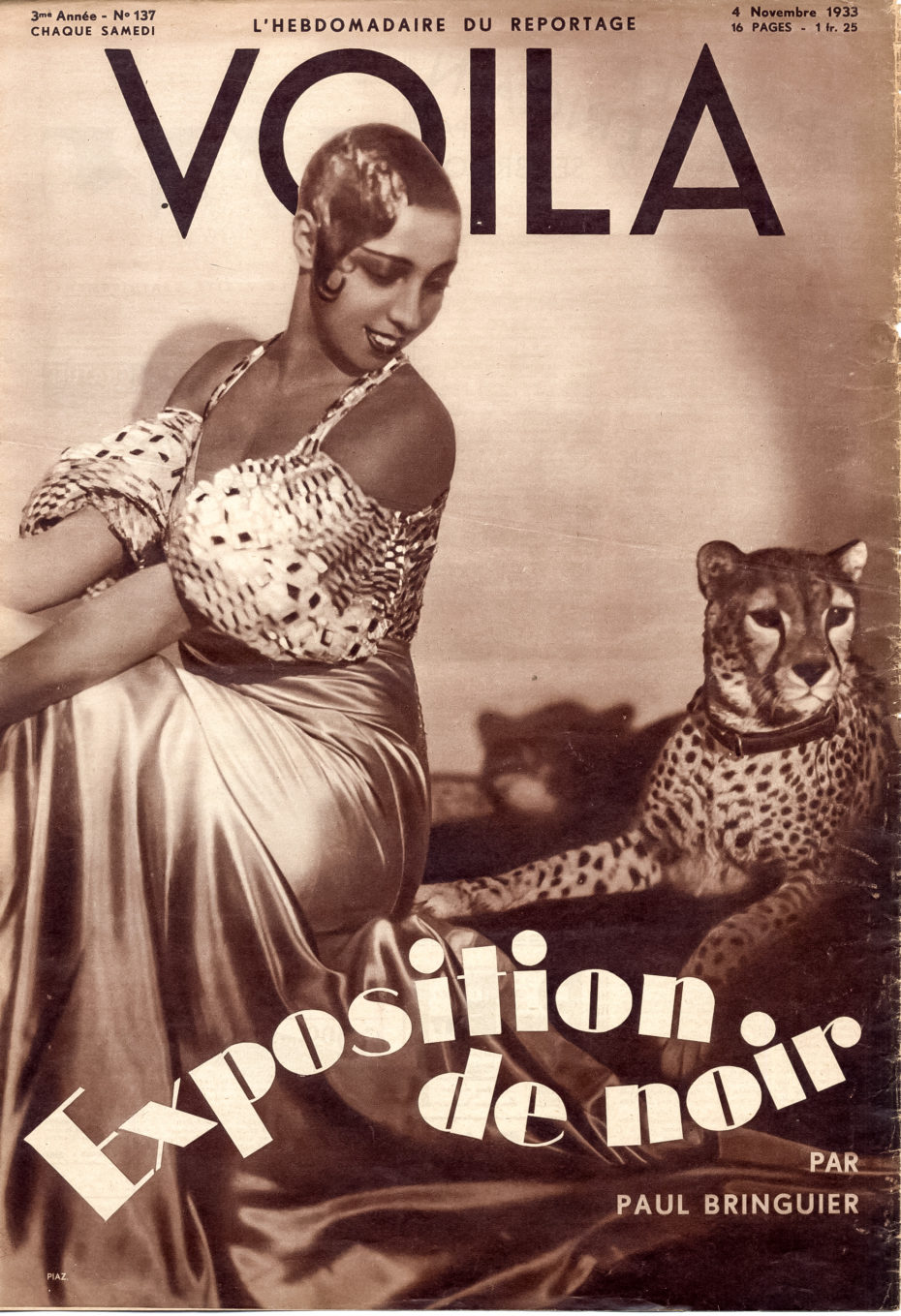

In 1925, Josephine Baker came to Paris with Le Revue Nègre and became an international sensation. A slapstick provocateur, she combined the erotic with the parodic, crossing her eyes while gyrating in nothing but bananas or a single strategically placed flamingo feather. Bricktop took her under her wing and the two may have started a romantic relationship. Within a year, Baker had opened up her own club in Montmartre, Chez Josephine.

The brilliant reed player Sidney Bechet, who would become one of the first important soloists in jazz, also came to Paris with Le Revue Nègre. Bechet was a genius but he had a volatile temper. He had already been deported from London in 1922 for getting into a brawl over a woman. In 1928, he got into an argument at Chez Bricktop with banjoist Gilbert McKendrick allegedly over a chord change. Bricktop told them to take it outside, but instead of cooling down, Bechet pulled out a gun and started shooting. He missed McKendrick but he shot stride pianist Glover Compton in the leg and wounded two women who were passing by. Bechet was sentenced to a year in jail and then deported. Compton spent several months in the hospital. When he asked Bechet to cover his hospital bill, Bechet told him to watch out for his other leg.

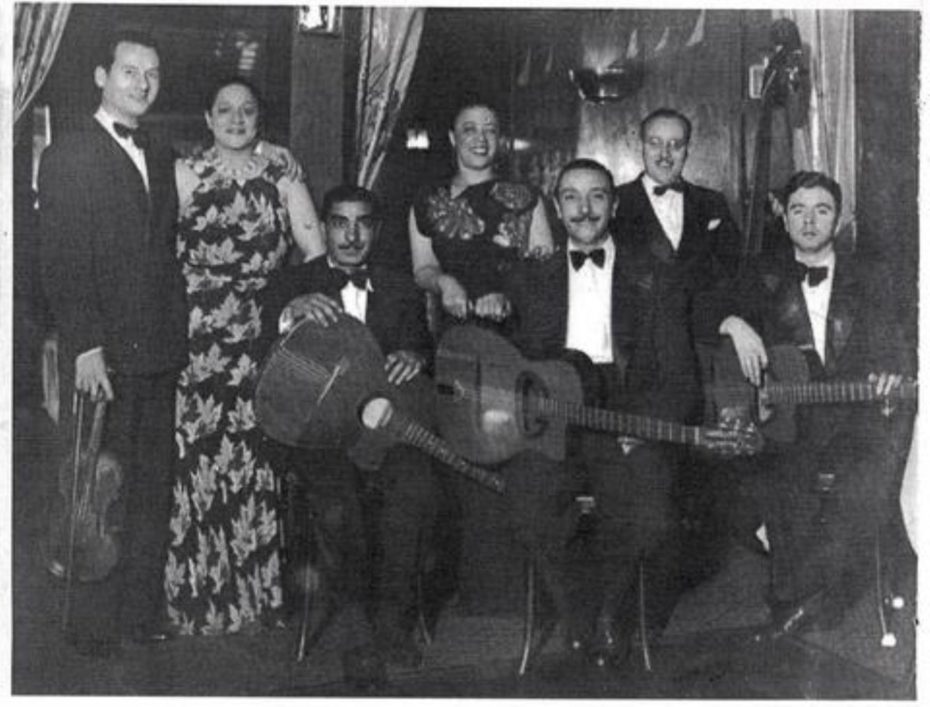

One of the major entertainers of the Harlem Renaissance, Adelaide Hall, who pioneered scat singing along with Louis Armstrong, came to Paris as the star of Blackbirds of 1928 and was the toast of The town during her four months performing at the Moulin Rouge. She returned to Paris in 1935 with an intention to stay. Hall moved to Montmartre and opened her own club, The Big Apple. It was known for its live radio program on Saturday night, led by bandleader Maceo Jefferson. Ella Fitzgerald and others later acknowledged her as one of the world’s first jazz singers and enjoyed a recording career that spanned eight decades.

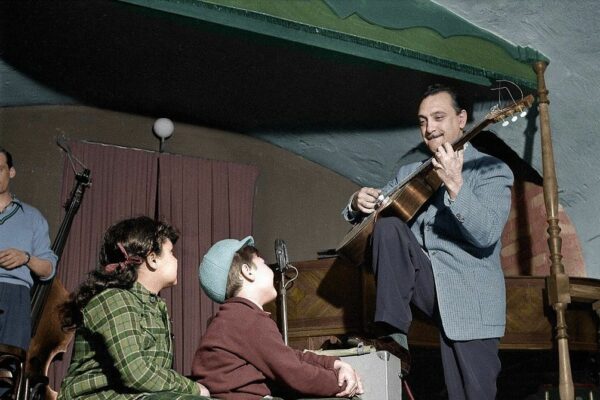

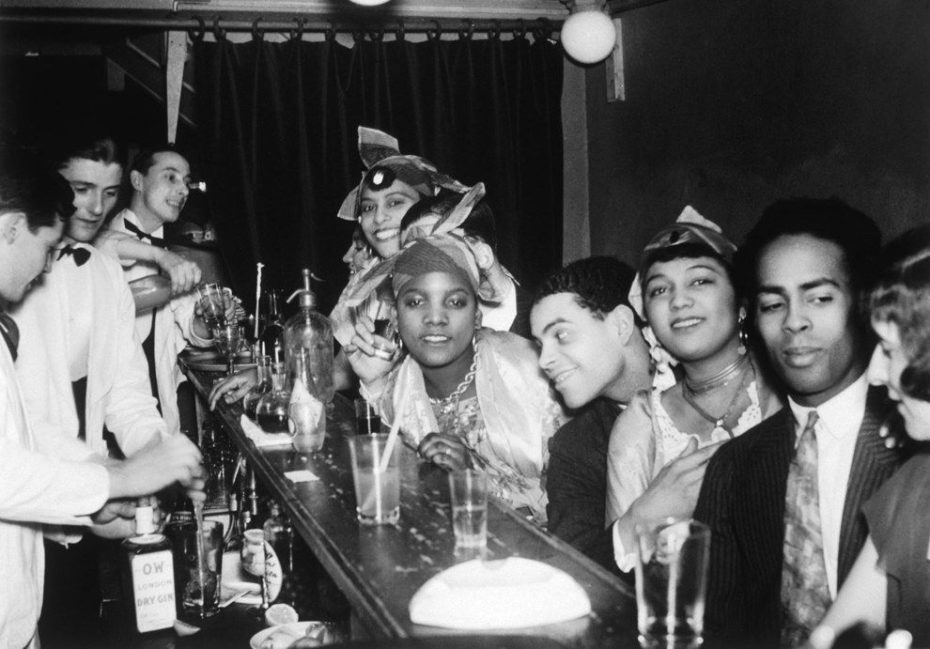

Jazz was not the only sound in Paris. There was also a strong Afro-Caribbean scene in Montmartre. In fact, a large percentage of the Harlem Hellfighters, the original jazz band in France, were Puerto Ricans of African descent. Many of the Afro-Caribbean clubs featured musicians from French islands, but in the shadow of the Moulin Rouge, there were so many Cuban clubs on Pigalle’s rue Pierre Fontaine, the street was nicknamed Calle Cubana. One of the best known clubs on this street was Cabane Cubaine. Regulars included Buster Keaton, Cab Calloway, Rita Hayworth, Prince Ali Khan, Anita Ekberg, and Maurice Chevalier.

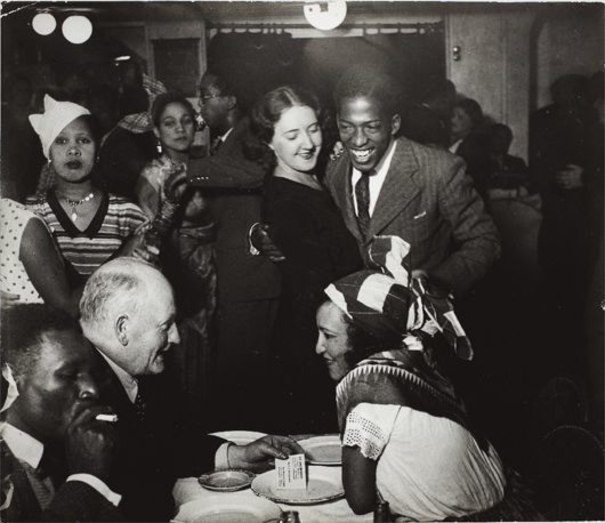

La Cabane Cubaine, Montmartre , ca. 1932, Brassaï

It should be mentioned that while Black and white patrons did freely dance and drink together in Montmartre, racism was still embedded in French culture. Black people were fetishized for being exotic and cartoons of the era depict them with bulging eyes and thick red lips. In 1931, the Exposition Coloniale opened in Paris, echoing troubling history of Europe’s penchant for “human zoos” and the French government’s preference for flexing their colonial power and superiority. Black Americans in Paris, however, revelled at the chance to experience such a huge display of artwork and music from Africa and the Caribbean. The Black American sculptor Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, who lived and worked in Paris, was so moved, that she wrote to W.E.B Dubois about the “heads of thought and reflection, types of great beauty and dignity of carriage” and declared that “people are seeing the aristocracy of Africa.”

A series of circumstances spelled the end of the Black American community in Montmartre. First, there was the Wall Street crash in 1929. The subsequent decline of American tourism due to the Depression hit the Parisian entertainment industry hard. Louis Mitchell closed up and went back to New York in 1930. But the real blow came with the French music union.

During the Années folles, French musicians were still just learning how to “swing” like their American counterparts, but by the 1930s, they were starting to get the hang of it. Django Reinhardt emerged as the best French jazz musician, mostly because he was Romani and an outsider to formal French music. Reinhardt had previously experienced difficulty finding work; not only was he discriminated against because he was Romani, but only Black people were being hired to play jazz in Paris. Bricktop and Adelaide Hall were practically the only people who would hire him. But with the growing threat of war came a growing Nationalism. The French music union managed to get a law passed that stipulated no more than 10 percent of musicians on the stages of Paris could be foreigners. As a result, many Black musicians were forced to leave. In 1936, beset with financial difficulties, Bricktop closed her iconic nightclub and went to Cannes.

The last strike against the Black community was the war. Germans started to arrive in Paris during the Exposition of 1937. There were so many Germans at Bullard’s nightclubs like Le Grand Duc, that French counterintelligence recruited him to spy on German officers. He was paired with an Alsatian secret agent known as Cleopatre Terrier. Together, they put on such a convincing show of welcoming Germans that Bullard was eventually shot by a Corsican gangster for being a Nazi spy.

In 1940, the Nazis hoisted the swatstika flag on the Eiffel Tower and marched into Paris. Bullard closed his nightclubs and went off to fight the Nazis in Orléans with his old regiment. After he was injured, his friends put him on a boat to America for his own safety. Baker left Paris under the guise of a tour to South America with Free French papers pinned inside her bra. She spent the war years in North Africa working with the French Resistance.

The Black Americans who stayed in Paris faced the racism of the Nazis. They were barred from performing and from entering most hotels, restaurants, and theatres. Eventually, they were arrested and placed in prison camps. Arthur Briggs, one of the most popular trumpet players in Europe, was sent to the prison camp at St. Denis. Maceo Jefferson, the bandleader at the Big Apple, spent two years in the prison camp in Compiegne. With jazz music banned for being a “degenerate” art form, both these musicians spent their years in captivity playing classical music and the fox trot for their captors.

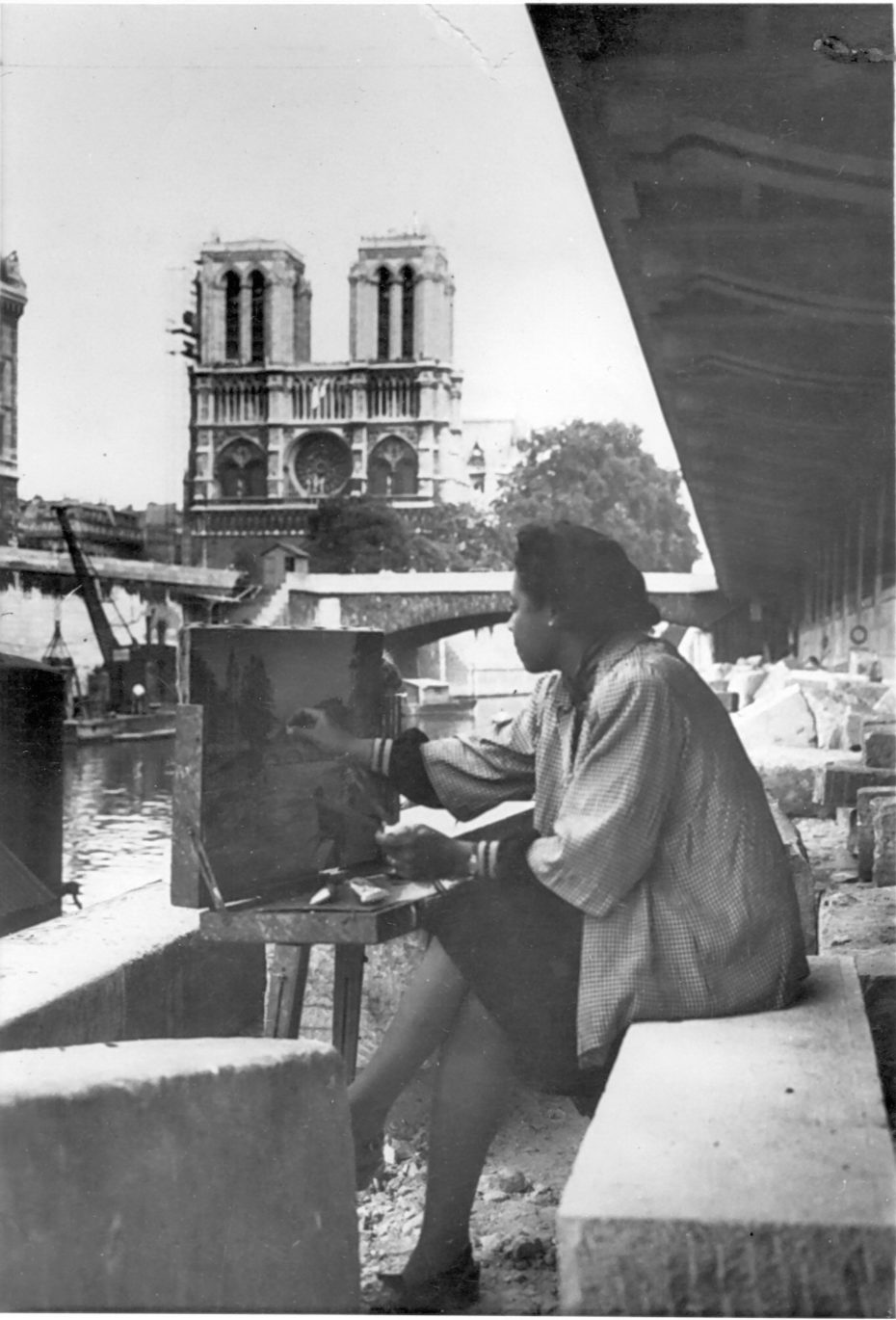

In the streets of lower Montmartre now, there are no traces of the Black community that once thrived there. For decades, Harlem-on-the-Seine was a lost chapter of Les Années Folles. But the jazz migration from America to Europe left a lasting legacy in other ways.

Not only did these Black pioneers create a new synthesis of music, but they also forged a new path for Black Americans. Harlem-on-the-Seine promoted the possibility of a world where Black people could have full citizenship. Just two generations from slavery, a new narrative of Black cosmopolitan experience was created for future generations to amplify.

About the Contributor