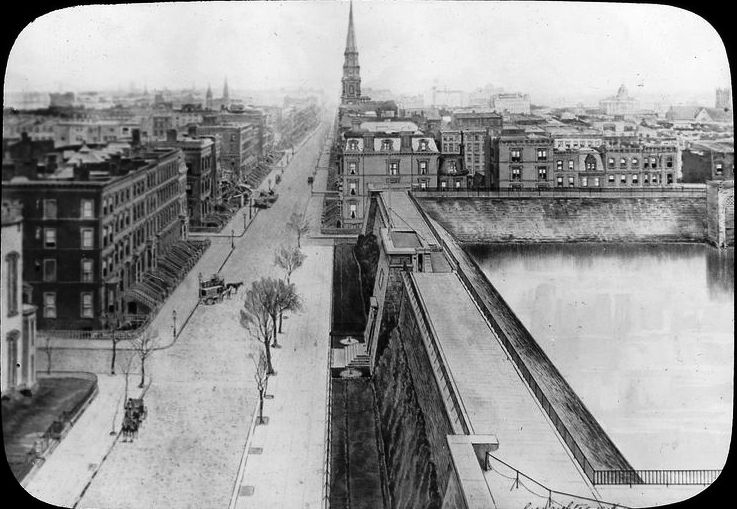

Bryant Park is one of Manhattan’s most popular public spaces. Basking in the shadow of the main branch of the New York Public Library, there you will find a bustling leafy oasis within touching distance of Times Square, filled with outdoor bars and cafes, a carousel, open air reading rooms and leisurely games of pétanque. But travel back in time one hundred and eighty years, and on the same site of this idyllic urban park you’d be faced with something pretty spectacular; a colossal stone structure looking a lot like an Egyptian Temple. Covering 4 acres (or 16,000 square meters) of midtown-Manhattan and towering forty five feet above 5th Avenue, what was even more incredible was that this Ancient looking monument was entirely filled with sparkling, clean water.

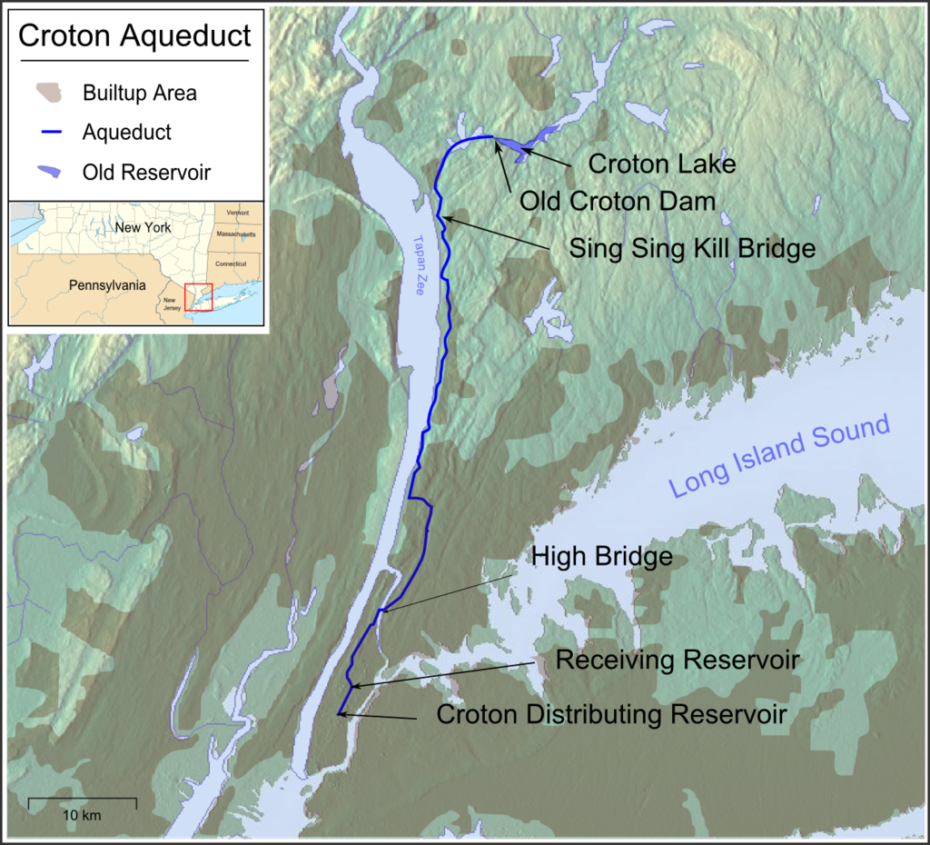

For in 1842, Bryant Park was home to the Distributing Reservoir of one of America’s most outstanding and ambitious industrial achievements: a forty one mile aqueduct designed to bring millions of gallons of fresh water into the city every day. Stretching from the Croton River in Westchester County and down into the City, the water supply flowed through an underground tunnel; and although it hasn’t been used since the 1950s, the tunnel is still still there, lying perfectly preserved and untouched.

Even more incredibly, above ground, the Croton Aqueduct became a nature trail and public right of way that follows the winding path of this long tunnel into Manhattan. It passes through people’s back gardens, grand mansions, and abandoned ruins; it bisects motorways, Main Streets and dense forests alike. In essence, to wander down the Old Croton Aqueduct Trail is to gain a behind-the-curtain glimpse of a New York that hardly anyone knows is there.

In the 1820s and 30s, Manhattan was a far cry from the gleaming metropolis of the Gilded Age forty years away. In fact it was in danger of disappearing altogether under its own filth: teeming with overcrowded slums and with no real sewage system, it was said you could smell New York City from three miles away. In 1836 the New York Mirror reported that the city, “was a realm of mud, its vast floor inundated with a slimy alluvial deposit, of the consistency of batter, of bean-soup, ankle deep……even Broadway was uncrossable.”

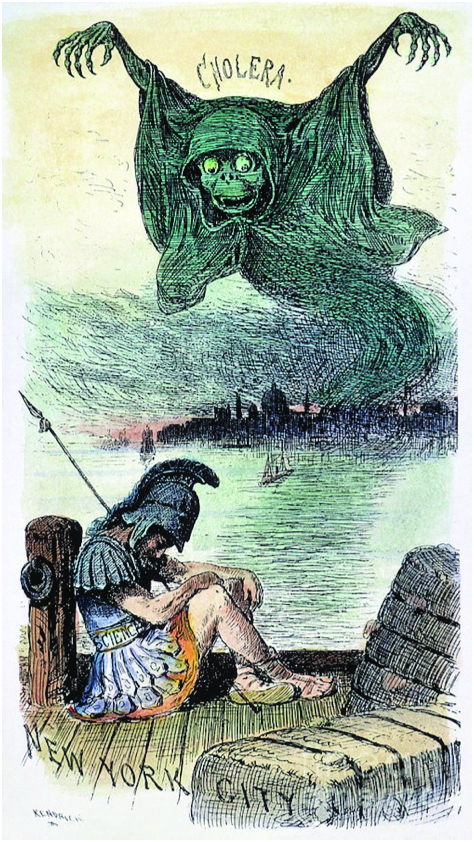

The chief problem was a lack of clean, healthy water. Despite being an island, it was virtually impossible to find fresh water anywhere in Manhattan: both the old creeks and few wells that existed were long since polluted. Street cleaning was nil, and the city was regularly ravaged by outbreaks of cholera, yellow fever and fires, as the mortality rate soared by the 1830s to an incredible one in every thirty nine people. “With what face canst thou issue forth into this sty?” decried the Mirror. “They got out in the morning arrayed like gentlemen and ladies, burnished with boots, decent trousers, white stocking and wearable frocks. They come home be-splashed, be-drenched and be-spattered, wearied with striding over stagnant pools.”

With Manhattan on the brink of being swallowed up by slime, the need for clean water became imperative. Fayette Bartholomew Tower was a young engineer who would work on the Croton Aqueduct. He published an illustrated guide to the achievement a year after its opening, arguing that, “a supply of pure and wholesome water is an object essential to the health and prosperity of a city.” New York City would build its modern engineering marvel by looking firmly at the past: specifically, the grand aqueducts of Ancient Rome.

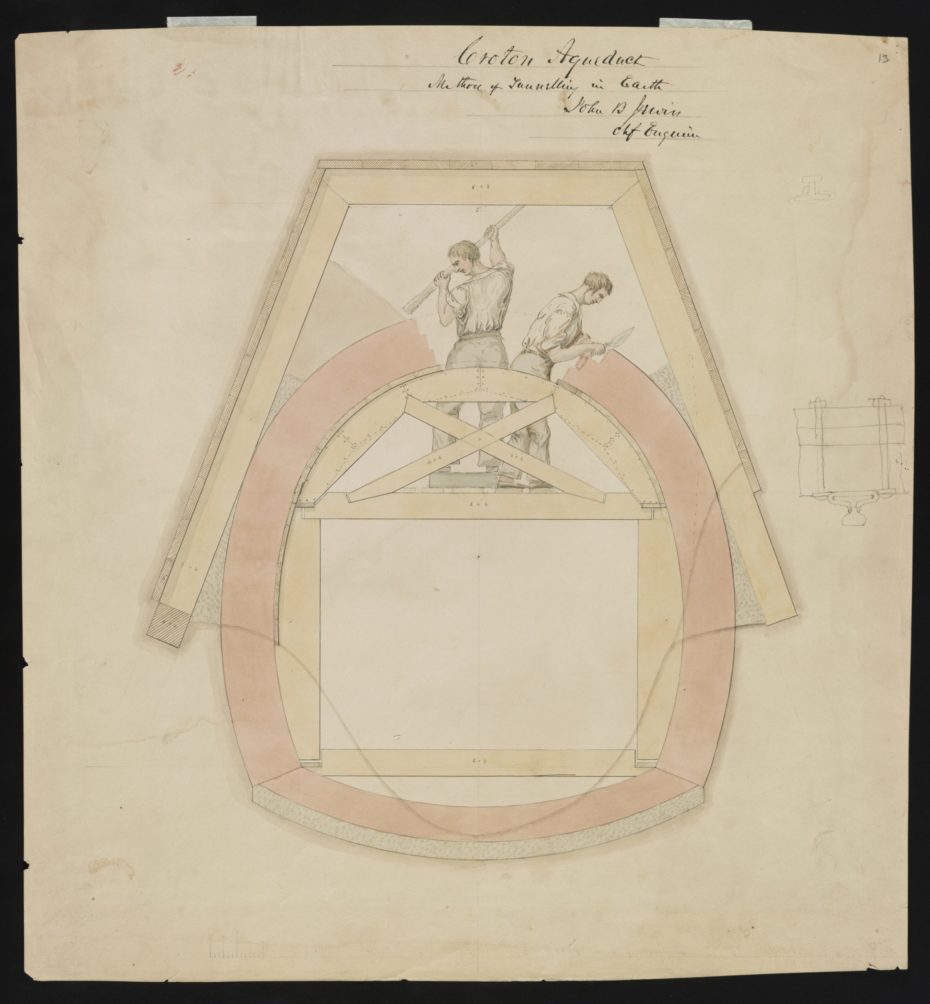

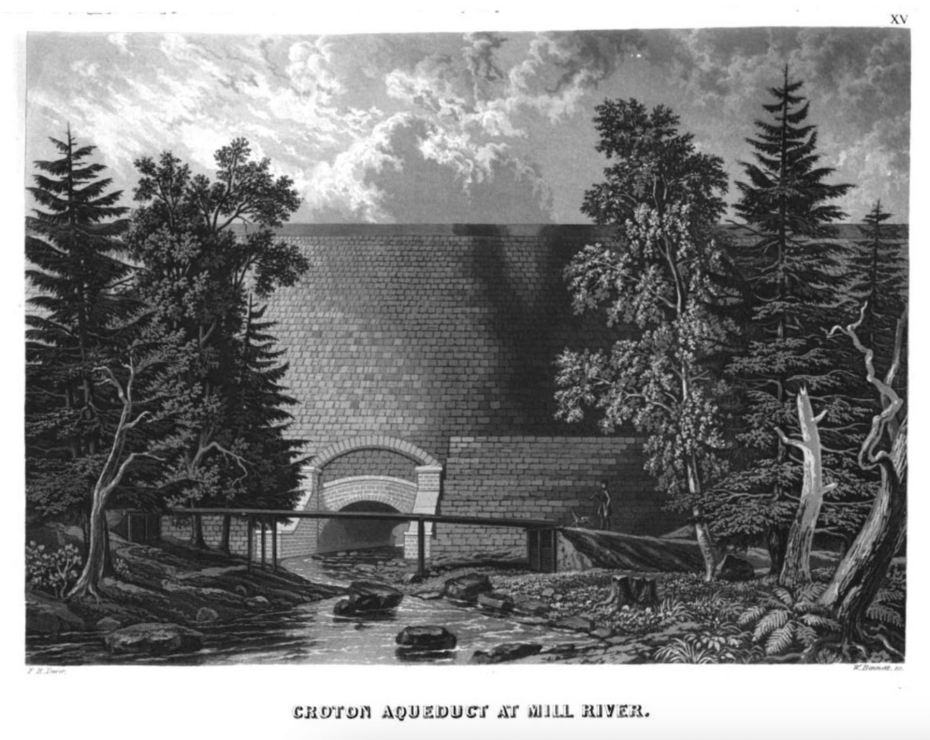

“We contemplate with mingled emotions of wonder and admiration,” wrote F.B.Tower in 1843, “those works of art which were achieved by Ancient Rome in her palmy days of wealth and power, and among them we find that her Aqueducts hold a prominent system.” Led by Chief Engineer John B. Jervis, construction began in 1837 to build a water supply system that would be powered purely by gravity. Starting at the Croton River, an iron pipe would drop 13 inches every mile, until it ended up in Manhattan, forty one miles later. The pipe would be encased in a brick tunnel 8.5 feet high and 75 feet wide, and along its journey, the Aqueduct would be cut into rocks, tunnelled underground, carried over streams, and across arched bridges, most of which you can still discover today by wandering the Old Croton Aqueduct Trail.

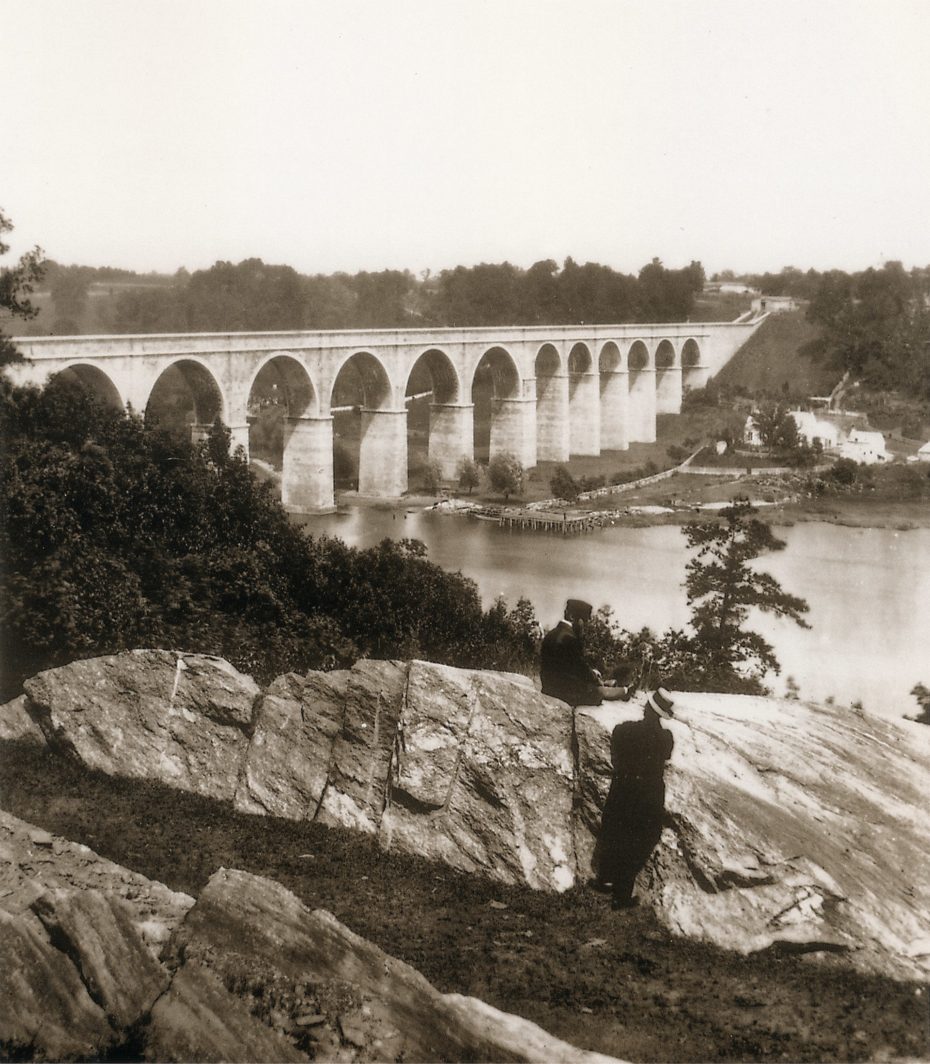

The water system would enter Manhattan at the last and grandest bridge of them all, the High Bridge, which still crosses the Harlem River today. The oldest bridge in the city had been left abandoned in the 1970s, until it was restored as a beautiful pedestrian walkway in 2015, where you can still marvel at its stone archways. “Its appearance will rival the grandeur of the Ancient Romans,” promised F.B. Tower. “With proper care in preparing the foundations of the bridge at Harlem River, there is no good reason to fear that it will be less durable than the Aqueduct of Spoleto….standing about eleven hundred years and is still in a perfect state of preservation.”

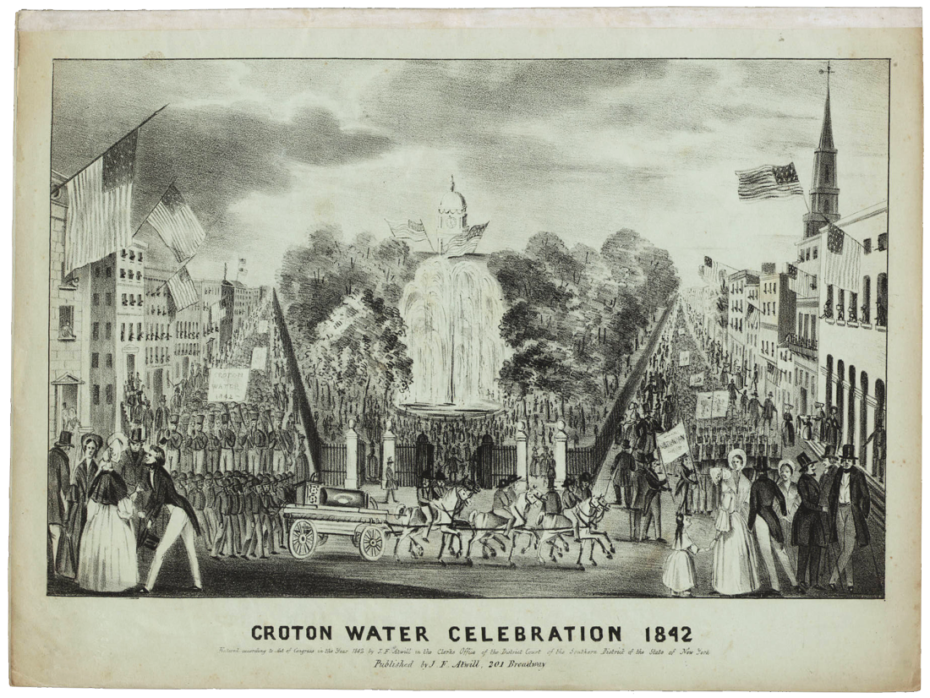

The building of the Croton Aqueduct was completed in 1842 after five years of back-breaking manual labour. As well as the Reservoir built on Bryant Park, a second vast reservoir was constructed in Central Park, occupying the space where today you’ll find the Great Lawn. As the clean, fresh water finally flowed into New York City, celebrations were held that rivalled Independence Day itself. Fayette Bartholomew recorded the event in a letter to his paramour, Helen Philips, studying at a woman’s only school in Troy, NY….

“At an hour when the morning guns had aroused but few from their dreary slumbers, and ere yet the rays of the sun had gilded the city domes, I stood upon the topmost wall of this Reservoir and saw the first gush of the waters as they entered the bottom and wandered about as if each particle had consciousness, and would choose for itself a resting place in the palace towards which it had made a pilgrimage, Or I fancied I could recognise the ‘Water Nymphs’ of the Croton, come from their rugged caverns to enjoy the refinements of a city residence.”

Four intrepid members of the engineering team actually boarded a small skiff they christened the Croton Maid, and sailed inside the length of the tunnel, appearing at the Manhattan end twenty two hours later.

October 14th, 1842 was set aside as a holiday, celebrating the 40-60 million gallons of clean water flowing into the City everyday. Down in City Hall Park, President John Tyler was joined by crowds to gather around an ornate fountain, “as the plume from the Croton-fed City Hall fountain surged 50 feet high,” wrote The New York Times, to the accompaniment of the New York Sacred Music Society singing a specially commissioned song, the Croton Ode:

“Gushing from this living fountain,

Music pours a falling strain,

As the goddess of the mountain

Comes with all her sparkling train.”

New York felt like a city cleansed and reborn, one newspaper celebrating, “Oh, who that has not been shut up in the great prison-cell of a city, and made to drink of its brackish springs, can estimate the blessings of the Croton Aqueduct? Clean, sweet, abundant, water!””

People lined the streets to watch the largest parade ever held in Manhattan, and stopped to marvel at a new sight: city parks beautified with fountains spraying clean water into the crisp, October air. Others would have headed home to enjoy the newly discovered comforts of a bath in their own home filled with clean running water.

From the very beginning, people were invited to come marvel at the Croton Aqueduct. “The foreigner who visits this country will find the Croton Aqueduct an interesting specimen of our public works,” wrote F.B.Tower, “and will be pleased with a pedestrian tour along the line of the work to the Fountain Reservoir among the hills of the Croton. …he may enjoy much that is beautiful in American scenery.”

The same ‘pedestrian tour along the line’ still exists today, twenty six miles of which was purchased by the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation in the 1960s. This linear park and trail winds its way from the Croton Dam down into Yonkers and is filled with historic sights, forests and urban centres.

Your first stop in exploring this long trail is to head to the first rate Friends of the Old Croton Aqueduct, a non-profit group of volunteers who protect and preserve the Old Croton Aqueduct, working to keep the historic greenway unspoiled.

With maps to guide your way, the group also put on underground tours and lectures, and keep a sterling museum in the only remaining Aqueduct Keeper’s Cottage, which can be found in Dobbs Ferry. Nearby in the city of Ossining, the group regularly open up one of the weirs that were built along the Aqueduct, where the flow of water could be diverted through an iron gate if repairs were needed on the tunnel. It also gives you the chance to descend into the abandoned tunnel itself, where you can still see the scorch marks where the $1 a day labourers used black powder to blast their way forty one miles southwards to Manhattan. The water has long since been closed off, and the air is clean and dry. As one writer put it, inside the abandoned tunnel you’ll experience the, “thrill to put your hands on brick walls that were laid well before the Civil War and haven’t been touched since.”

One such volunteer is Thomas Tarnowsky, a retired photo editor who has spent years researching, collecting images and writing about the engineering marvel that brought clean water into Manhattan. “On the surface, things look simple,” he explains. “”You turn on your faucet and water comes out. No one understands what it takes to make it work, and in 1842 New York, it was nothing short of a miracle.”

Above ground, following the route of the Aqueduct tunnel is an unparalleled opportunity to explore New York’s back yard, ranging from dense forests to the urban city. “Most people are not aware of its existence. The whole trail walking south from the Croton dam is a country like atmosphere…something like it would have been 175 years ago. You’ll pass through rock cuts, high embankments, seventy feet high overgrown man-made structures.”

One of the first discoveries you’ll make hiking the Old Croton Aqueduct Trail are giant stone columns appearing once every mile or so. “These are ventilation hollow cylinders of stone,” explains Tarnowsky. Rising fourteen feet high, they “allowed clean air into the tunnel, and equalised the water pressure, that rose or fell depending on the dam itself.” Today, as you wend your way through some of the more urban stretches where the dirt trail becomes concrete sidewalks, they can appear like an old friend, guiding you to keep on the path of the Aqueduct Trail.

Here is just a small selection of some of the places to explore as you wander down this hidden backroad of New York…

The Grand Central Stones

Found in Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx (also home to New York’s first public golf course!) you’ll find a peculiar row of similarly carved, ten feet high stone pillars in the wood. Resembling a miniature stone henge, the thirteen pillars were actually made of different stones such as marble and limestone. They were placed outside as a test to see which would weather best on the facade of Grand Central Terminal. The winner was Indiana Limestone!

The Ruin Gates of the Beechwood Estate

Found where the trail passes along Route 9 near Briarcliff, these ornate gates are all that remain of a mansion once owned by Frank Vanderlip, one of the founders of the Federal Reserve. These giant Classical stone columns used to grace the First National City Bank of New York at 55, Wall Street, before Vanderlip had them brought to where they rest today.

The Abandoned Railway Bridge

Located in Hastings-on-Hudson, and hiding underneath the trail is a stone arch bridge that was once part of a small railway connecting a stone quarry downhill to the Hudson River.

The Gate House Ruins at the Untermeyer Estate

Guarded by monumental sculptures of a lion and a unicorn, this ruined gate house is your entryway off the trail and into the mysterious and marvellous Untermeyer Park and Gardens in Yonkers.

The one hundred and fifty acres of beautiful parkland were filled with architectural wonders and oddities by lawyer Samuel J. Untermeyer, including a verdant Persian garden, two thousand year old columns, remnants of ancient temples, and canals representing the four Biblical Rivers. Left to neglect after Untermeyer’s death in the 1940s, the ruins of the estate gardens became a meeting place for Satanic groups in the 1970s, including David Berkowitz, the ‘Son of Sam’. Behind the ruins of the old gate house, make sure to investigate a carved archway in the rock, where you’ll find a small fountain in what is known enigmatically as the ‘Devil’s Hole’

Recent years have seen the beautiful gardens mostly restored and today it’s one of New York’s more unusual and breathtaking gardens to visit.

The Armour-Stinson House

One of the most striking houses in America, this fairytale looking pink octagon shaped house can be found in Irvington. Modelled after Bramante’s 1502 Tempietto in Rome, the beautifully ornate home with an eight sided wrap around porch was built for financier Paul Armour in 1859. Perfectly renovated by the Lombardi family, tours are available to explore this most magical of houses.

The Ruined Greenhouses and Swimming Pool of Lyndhurst Mansion

This gothic masterpiece just south of Tarrytown resembles an imposing “Downton Abbey” overlooking the Hudson River. The former home of railroad tycoon, robber baron of the Gilded Age and one of the wealthiest Americans of the late 19th century, Jay Gould, is adorned with turrets and towers, with an exquisite wooden bowling alley built on the grounds.

The Croton Aqueduct Trail passes right through the beautiful estate, and our favourite corner is where you’ll find the ruins of a grand indoor swimming pool, and the astonishing remnants of what was once the largest and best equipped greenhouse in America. Filled with orchids and roses, today the abandoned rusting greenhouse gives a glimpse of the untold wealth of Jay Gould. As one woman of the time is said to have remarked of the robber baron, “surely a man cannot be altogether bad who is a friend of the roses.”

Sunnyside, Home of Washington Irving

This picturesque, fairytale looking cottage in Tarrytown was the home of America’s first great novelist, Washington Irving. People have been long been drawn to this charming cottage in the woods; when F.B. Towers wrote his guide to the Croton Aqueduct back in 1843 he reported, “As we approach Tarrytown, we find the localities which were pictured in the Legend of Sleepy Hollow, an easily recognise the Old Dutch Church near which the affrighted Ichabod Crane was so sadly unhorsed by the headless Hessian. Besides the romantic and diversified scenery of the Hudson which is in view from the line of the Aqueduct, the visitor may find highly cultivated grounds and delightful country seats, among them that of our distinguished countryman, Washington Irving……”

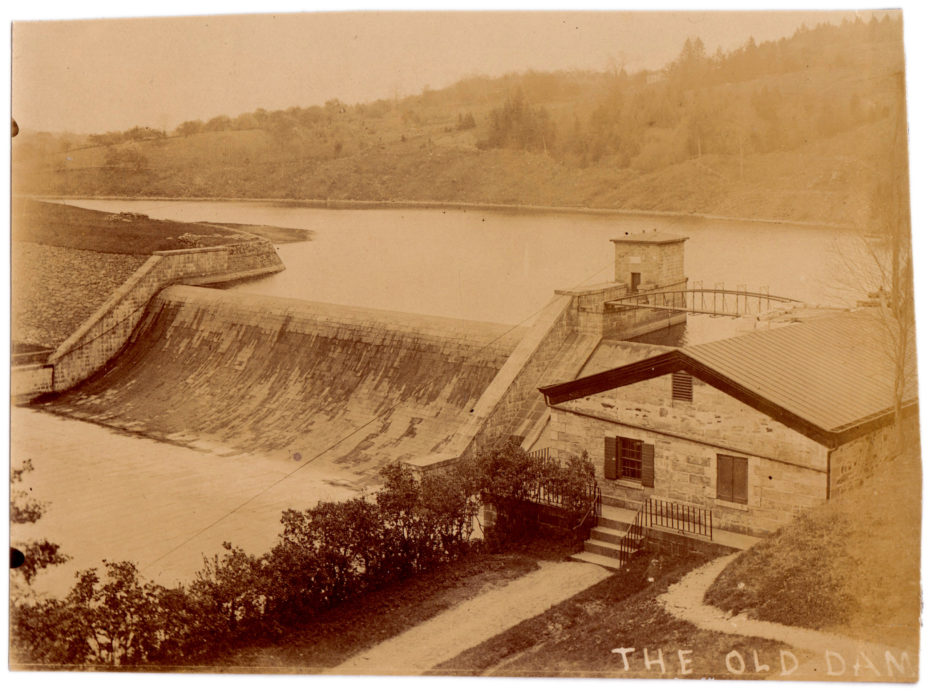

For all its engineering expertise, supply for clean water swiftly outgrew the Old Croton Aqueduct, and in the 1890s a second tunnel was built deeper underground. The dam in Croton was upgraded at the same time to the majestic spectacle you will find today, although the original dam is still there, lying forgotten forty feet under the water. Still today, nearly 10% of Manhattan’s water comes from the 1890s New Croton Aqueduct.

The Old Croton Aqueduct Trail remains one of New York’s hidden treasures; as you follow its path, it is easy to forget that five feet below is an abandoned brick tunnel that passes through Westchester, Yonkers, the Bronx and Manhattan. In many places, the old trail and its bridges, culverts and archways have become overgrown, much as F.B. Tower predicted back in 1843, when he wrote, “ the wild vines will soon climb over the walls and cover them; vegetation will cover over the work until nature and art be harmoniously wedded.”

Whether you wander the trail alone, or in the company of the Friends of the Croton Aqueduct, F.B. Tower offered the best advice a hundred and seventy eight years ago: “It is unnecessary to speak further of the objects which are calculated to interest the visitor to this part of the country: we would only invite the stranger who visits the city of New York to go forth and visit her noble Aqueduct!”