If modern art has taught us anything, it is that anything can be considered art. Picasso’s and Braque’s curious peeling newspaper collages of the 1910s spring to mind as the opening act for the ‘Modern Art’ movement. It was at this point in time, in the early 20th century where ‘real’ art – the academic 19th century kind, with all its airs and graces and establishment-imposed ‘rules’ – and this new lighter, less formal and somewhat random approach, parted ways. Modern Art as we perceive it was arguably launched by the quirky and wonderfully chaotic Dada movement that took root in central Europe around 1910 and flowered in New York in the early 1920s, causing a somewhat profound ruffling of the feathers of the status quo. And whilst we now see Dada as revolutionary, it was uncanny to discover that Dada had a look-a-like predecessor – not a direct ancestor, mind you, more like a forgotten uncle. ‘Les Incohérents’ was a short-lived French art movement that originated from Montmartre in Paris in the 1880s. Unconcerned with the intellectual, political or spiritual facets of the arts (which Dada would address a mere 20 years later), they did, however, attempt to question through satire and ridicule, what exactly ‘art’ was, who it was intended for and why on earth it had to be so darn square.

Paris in the 1880s was the capital of a flourishing world empire, serious and secure. Perhaps it could afford some cultural introspection and self-analysis, if only for its own entertainment? If beauty is in the eye of the beholder, then the Incoherents movement had a point: why restrict the arts, visual, music or dance world to the same old tedious and traditional offerings? Why not open it up to fun, new rules and new media?

As a small group of self-publicists, Les Incohérents were fed up with the stale and rather dull version of the-then established Arts world and wanted to entice the public with an alternative and more joyful view on art and life.

Playful, ingenious, ridiculous and entertaining, the Incoherent’s message was delivered through social amusement of the public, not unlike today’s social media content. This was to be an art for all, not just for a chosen few intellectuals. There’s indeed nothing new under the sun: from the graffitied walls of Pompeii to the current explosion of self-indulgent imagery on the likes of Facebook and Instagram, it’s human nature to tease and tinker with mainstream messages and offer an alternative opinion.

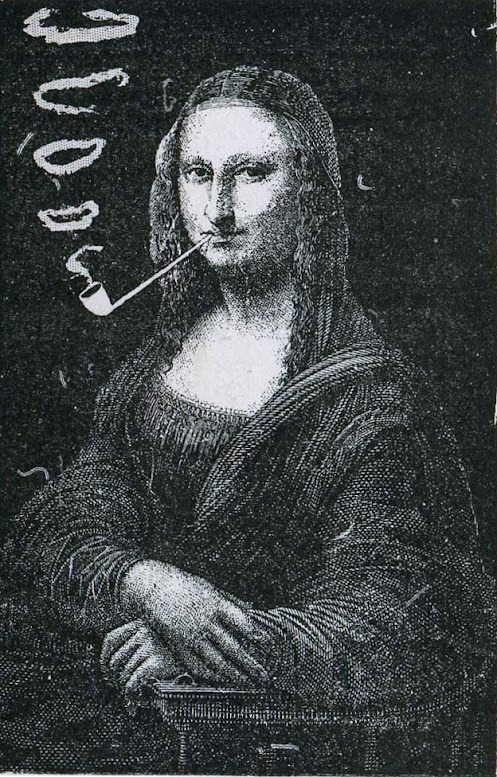

The Mona Lisa of the movement is quite literally, the Mona Lisa herself, enjoying her long clay pipe. Mona Lisa fumant la pipe created by the artist Sapeck (AKA Eugène Bataille) in 1883, is perhaps Les Incohérents’ most iconic identity piece. The crude application of the pipe and its smoke rings, shatters the reverence of the historic image, and let’s face it, Sapeck’s subject is clearly far more relaxed than Leonardo’s. No longer part of an exclusive private collection or purely the intellectual property of the elite, street art was now there for all to enjoy. Technological developments in printing and photography allowed ease of artistic appropriation of established iconic images and masterpieces. Contributors of the Incoherents movement continued to manipulate and distort all aspects of the Arts, from dance to opera, from poster art to photography in an attempt to provoke and rewrite the rules as to what ‘art’ was and who it was for.

The founder and leader of the movement was Jules Lévy, a Parisian writer, publisher and founder of a wine-loving literary club out of Montmartre during the Belle Epoque called Les Hydropathes, which had fizzled out in 1880. Working in newspapers of the day and familiar with volume printing and understanding the public’s appetite for news, in an anti-establishment move, Levy had decided to throw a public ‘exhibition of drawings by people who could not draw’. Billed as a charity event, the contributors could present works in a public forum. This was the first ‘Incohérent’ art exhibition, held on July 13th 1882 on the Champs Elysées. Appropriately, in true Incohérents style, the Champs Elysées show was extravagantly lit by candlelight due to a gas outage. A profusion of works were shown; drawings of all types, paintings littered with alternative and radical subject matter, miscellaneous sculpture and objects in all mediums and forms. These consisted of nonsensical, irrational and bizarre imagery, all engineered to question, provoke, engage and get a laugh from the public.

The success of the Champs Elysées event prompted Lévy to run a second show from his own tiny attic apartment in October 1882 which attracted some 2,000 people including Édouard Manet, Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Richard Wagner. Imagine the art world’s most famous artists and critics crowded together to see over 150 works in a chambre de bonne (Paris’ matchbox apartments reserved for domestic workers). A stark contrast to the pomp and elitism of the prestigious art ‘Salon’ and its official circuits, it was nothing short of a parody. One academic called the radical counter-salon “an attack on art”.

The public was actively invited to engage with this new art through the mocking and mannering of old icons. To say they were intrigued and amused is an understatement. They were gagging for more. Masked balls and cabarets were advertised across the city as the vehicle for delivering their message, attracting the public to a variety of venues and experiences where a jumble of different media, random objects, miscellaneous artefacts, scratchings, pastings and other weird and wonderful objects would be exhibited. A sort of arts ‘rave’ of the day.

Les Incohérents, whether it was a ball or a happening or an exhibition, became a ‘must do and see’ event in the Parisian cultural calendar. October 1883 saw the first official exhibition of Incoherent art at the Galerie Vivienne in the heart of Paris. This show and all their future events would be run for charity, with the guidelines ‘All works are allowed, the serious works and obscene excepted’. The show was an Aladdin’s Cave of absurdities, parodies and pictorial puns and was furnished with a formal catalogue of the works, giving us some idea today of just how bizarre the content was. A whopping 20,000-plus enthusiasts visited the exhibition that October.

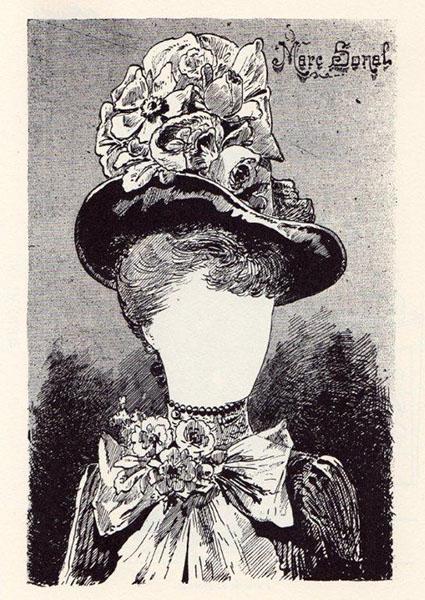

The next year, the Incohérents were again at Galerie Vivienne with yet more artful amusements. This time the catalogue, now effectively their manifesto, was lavishly illustrated with engravings of the peculiar works. The invitation card showed a ghostly broom-wielding dancer chasing blackbirds, perhaps an allegory for ‘out with the old and in with the new!’ The newspapers relished the event and as for the public, nothing could gratify their insatiable appetite for ‘incohérent art’.

Les Incohérents gave the Parisian public and celebrities of the day a chaotic and absurd serving of the visual arts, a barrage of eclectic offerings and experiences. Whilst never shocking nor challenging, the events were joyfully anticipated and was very much ‘a thing’ to attend and be seen attending in the Paris of the 1880s. But by the end of the decade, the success of the movement was catching up with Lévy. Accused of commercially exploiting both his artistic contributors and his public, the press began to describe him as a new form of the establishment, ‘the official unofficial Incoherent’. To add insult to injury, other enterprises in Paris started to cash-in on the branding, badging new cafes and titling magazines with the movement’s name and likeness.

In order to distance himself from his accusers, Lévy organised a masked funeral ball at the Folies-Bergère nightspot to mark the end of the movement. In 1891, Levy tried to relaunch the movement with a new magazine, ‘Folies-Bergère’, but this also struggled to capture public attention. One last exhibition in 1893 was described this time by a critical press as ‘all that is outdated, outmoded. Inconsistency joined decadence, decay and other jokes with or without handles in the bag of old-fashioned chiffes’. Lévy plodded on until 1896, still trying to be the good Svengali and showman but his movement had flowered and wilted, and its audience had moved on for titillating entertainment elsewhere. Les Incohérents would be momentarily ressurected stateside in 1919 when Marcel Duchamp appropriated the Mona Lisa image, but this time, in place of Sabeck’s pipe, she now sported a moustache.

So little of the movement’s works is thought to have survived, that when the Musée d’Orsay devoted a retrospective to the Incoherent Arts in 1992, it was only able to exhibit archival documents and press clippings. Thousands of works produced by hundreds of artists during the movement’s zenith had all disappeared. Even by the 1930s, surrealists like André Breton, who often spoke about the Incoherents, had never seen their works.

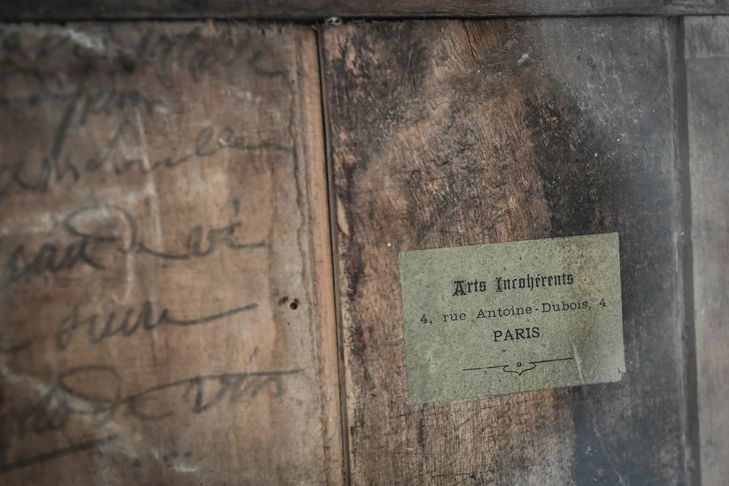

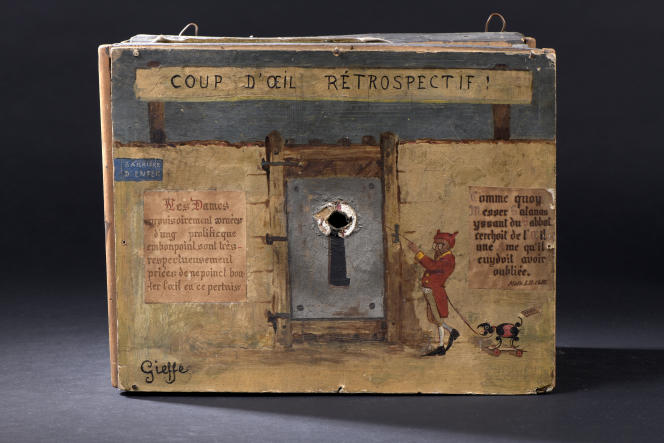

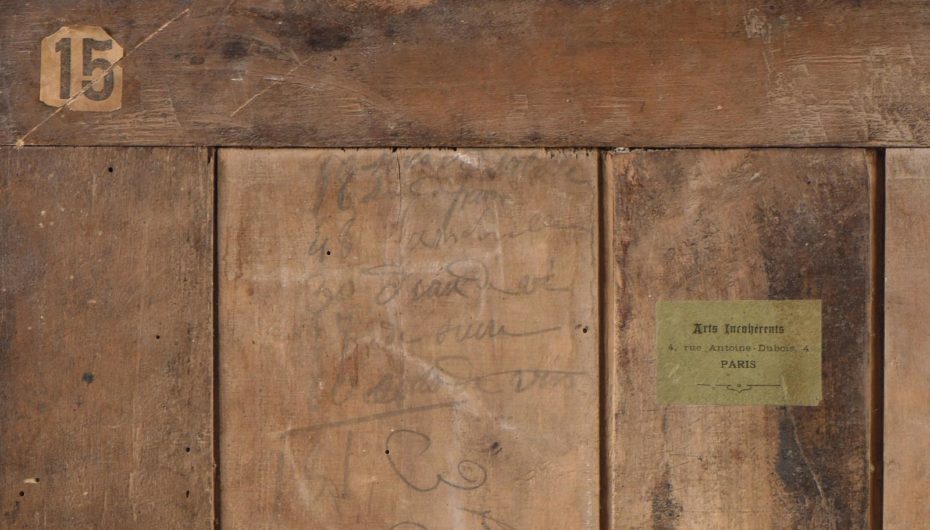

With few traces of its existence, the movement was practically a lost legend; but more than a century later, unexpectedly in early 2021, seventeen important works attributed to the Incoherent Arts exhibitions were discovered in an old trunk. Unearthed amongst the storage of a private home near Paris, the large trunk full of a “jumble of documents, drawings, objects wrapped in rags,” included one work which has since been identified as the first monochrome in the history of art.

Another important find amongst the trunk’s contents was a piece of green cab curtain suspended from a wooden cylinder created by Alphonse Allais, given a title that roughly translates to “Pimps still in the prime of life and their stomachs in the grass drink absinthe“. To the untrained eye, it might look like just an old swatch of antique fabric, but the piece actually predates the Dada movement’s “readymade” philosophy, a term coined by Marcel Duchamp to describe works of art he made from manufactured objects, such as his famous Bottle Rack (1915), the iconic porcelain urinal he titled Fountain (1917) and Bicycle Wheel (1913).

Unaware of the mysterious trunk’s value or significance, the homeowners were unable to identify its original owner – perhaps a co-organiser of Les Incohérents, one of the movement’s artists, or an early collector? Dealer and art expert, Johann Naldi, is still searching for answers while planning to present his findings to the public at the end of 2021, when the collection is also expected to go up for sale as a single lot. The Musée d’Orsay is rumoured to be a likely buyer.

And yet for such a historic find, bringing this collection to the world’s stage could be far more problematic that some would probably hope having just uncovered a missing link in the history of modern art. The problem being; the collection’s centrepiece, a canvas entirely painted in black, now identified as art history’s first monochrome, entitled “Combat de Nègres dans la Nuit“, which translates to “Negroes Fighting in a Cellar at Night”.

The provocative “joke” painting by the poet Paul Bilhaud, exhibited at the very first ‘Incohérent’ art exhibition in 1882 on the Champs Elysées, was thought to be lost forever. And now here it is, having resurfaced nearly 140 years later, facing a very different 21st century audience in the wake of a global racial reckoning.

Perhaps tellingly, the international press has been uncharacteristically slow to pick up a story about the rediscovery of an entire art movement hidden inside a trunk. Mainstream newspaper Le Monde however, has followed the story among other French art world publications, describing Paul Bilhaud’s historic monochrome as the collection’s most significant attraction. Meanwhile, the French Ministry of Culture has declared the collective discovery a “national treasure”. Disappointingly, we found that the French media coverage thus far has notably and consistently avoided any acknowledgement of the inevitable outcry that would likely ensue were a racist artwork disguised as humour to find its way into a public museum today and be celebrated as a national treasure.

As a conceptual piece, it is decades ahead of its time, which is where experts no doubt find the majority of the work’s merit. But is it worth elevating as the movement’s pièce de résistance or better used to reopen the conversation about what we consider art? It’s possible these issues are being raised behind the scenes before the collection is presented on a larger international stage.

In many ways, the Incoherents did create flickers of the avant-garde before the avant-garde. The movement momentarily released the public perception of the arts from the confines of its establishment, but it was Dada that actually managed to break the mould of previous centuries’ art traditions. Where the Dadaist created art for the mind, Les Incohérents was perhaps more of an amuse-bouche; a teaser of things to come. Now it’s our turn again to decide what to celebrate as art for public consumption.