We often try to avoid death. Sweep it under the rug, pretend it doesn’t exist and live in comfortable denial. But we weren’t always this way. In fact, many past societies have been completely obsessed with death, as seen in their art, literature, and philosophy. It can all be examined through a study of one phrase: memento mori. Latin for “remember that you die”, the expression has its roots in various philosophical and political movements dating back to antiquity.

The themes of memento mori could be traced all the way back to Socrates, who once described philosophy as being “about nothing else but dying and being dead.” But legend has it that memento mori as a phrase was first used as a way of keeping Roman emperors’ egos in check. After a military victory, when generals would parade through cities celebrating their triumph, it was decided that an enslaved person would be designated to sit and whisper a phrase like “memento mori” in his ear throughout the procession.

The saying became more and more popular and was quickly adopted by the Stoics: among them Marcus Aurelius, Seneca, and Epictetus, who encouraged his students to think of the phrase each time they embraced a loved one as a way of cultivating detachment. Marcus Aurelius developed the concept of memento mori in his Meditations: “You could leave life right now. Let that determine what you do and say and think.”

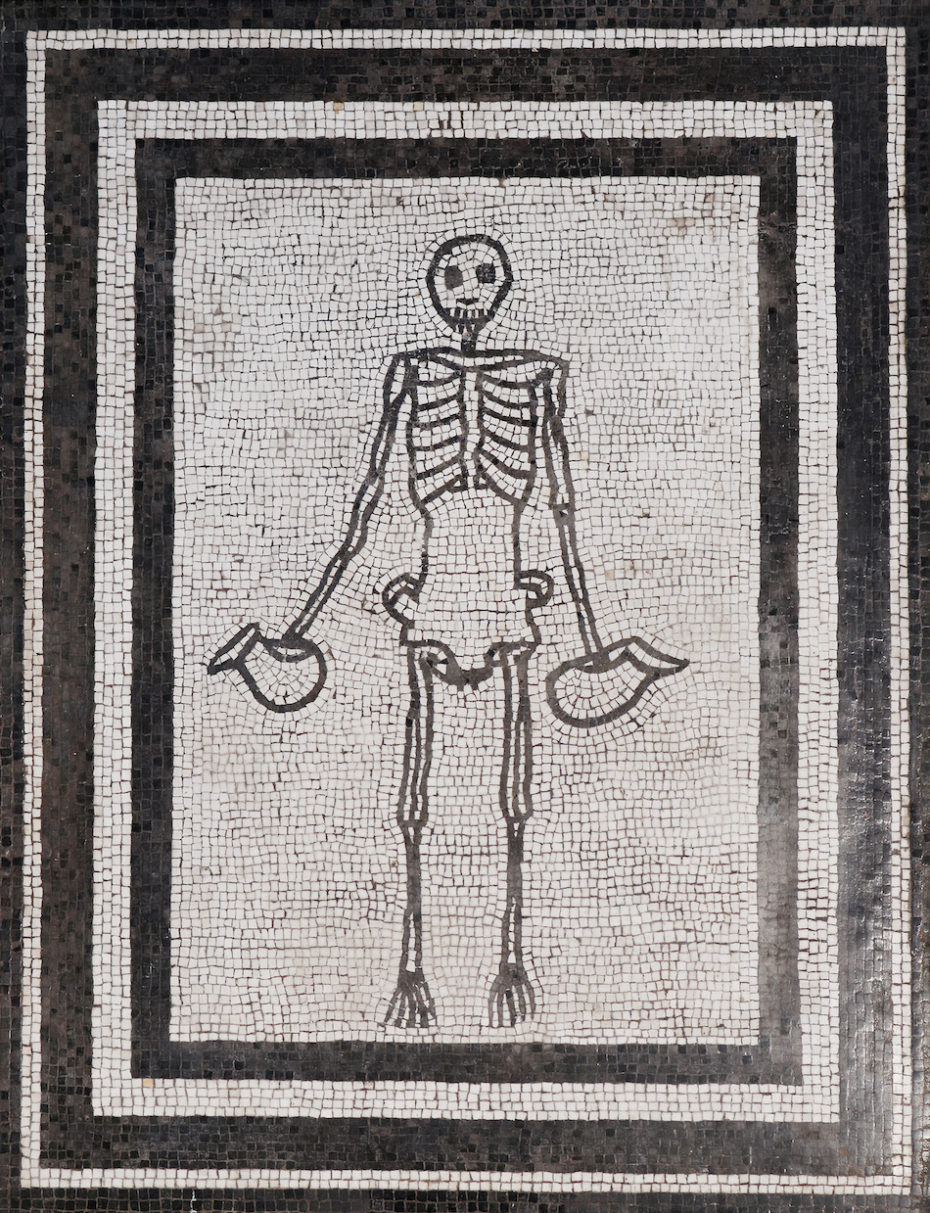

In a culture where mortality rates were so high, rituals for the deceased were common, and this proximity to death somewhat destigmatised it. That isn’t to say people didn’t grieve at funerals, but there was an equal amount of normalcy, dare we say joy, associated with the death of a loved one. There was even a February festival, Parentalia, that celebrated the dearly departed for nine days on end. Hence, the elaborate tombs of the ancient world, which often doubled as a cooking and dining spaces for surviving family and friends to break bread, drink wine and celebrate…

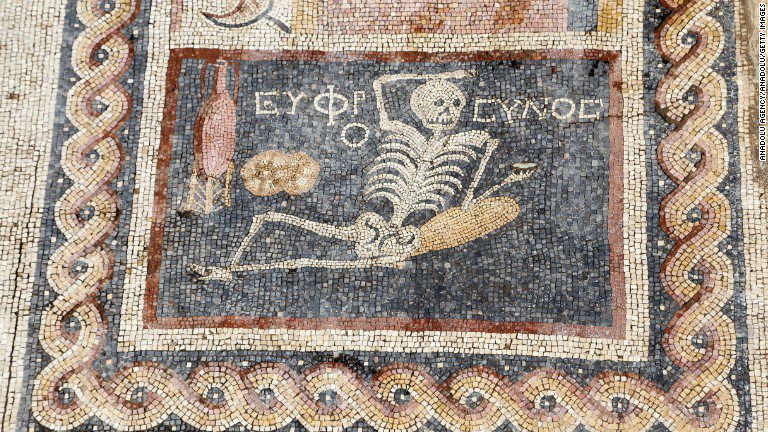

A 3rd Century BC mosaic skeleton depicted with wine at the ready, and the ancient equivalent of “Be cheerful, enjoy life” floating proudly above its skull, has been touted as history’s original YOLO (You Only Live Once) moment, and a reminder that the Romans’ reputation for indulgence wasn’t just pure gluttony. It was a way to reconcile the crippling fear of death with a better way of living, of preferring to dance, rather than wallow their way into the grave.

Similar practices of reflecting on death date back to early Judaism, Christianity, Islam, as well as Buddhism. A sect of French Hermits called the Brothers of Saint Paul (also known as the Brothers of Death) used Memento mori as a salutation when greeting or bidding adieu to one another. Maraṇasati is a Buddhist meditation in which one remembers that death is imminent, could strike any time, and therefore one must heighten one’s awareness of the present moment. Some monasteries have even hung human skeletons in meditation halls to serve as a visual reminder.

Speaking of visual reminders, this brings us to the history of art and the representations of memento mori that can be found within it. Perhaps the most direct version of memento mori in art is the Danse Macabre or the Dance of Death motif. Popularized during the Middle Ages and often featured in church frescos or exterior decoration, the Danse Macabre shows a personification of death leading several people towards the grave.

The characters walking with death are drawn from a variety of social statures, kings and popes walk with children and peasants and everyone is headed in the same direction. It’s thought that the first depiction of the motif appeared on a wall of the Holy Innocents’ Cemetery in Paris, dating back to 1424.

The scene was often acted out in costumed pageants performed in villages and at royal courts, in rituals that are considered by some to be the early origins of Halloween. Many other versions of the Danse Macabre still exist and span across Europe and seems to have been used to make the church’s message of piety explicitly clear.

And perhaps nothing helped monks and churchgoers reflect on mortality better than being surrounded by thousands of human bones, artfully arranged as decorative embellishments. Europe’s churches are home to some of the largest and best-preserved collection of ancient human skulls and bones in the world. One of the most famous temples to celebrate “memento mori” is the Sedlec Ossuary, in Prague, also known as ‘The Bone Church’, with its massive chandelier hanging from the ceiling, said to be constructed of one of every kind of human bone. Today it is one of the most visited tourist attractions in the Czech Republic.

Memento mori was also seen in more secular genres of art as well, which brings us once again to the vanitas, a particularly macabre sub-genre of still-life painting. As a refresher from our archives, when we dabbled in the secret language of still lifes, the subject became popular in the Middle Ages as funerary art, and could be extremely morbid and explicit, reflecting an increased obsession with death and decay…

Author, cartoonist (and self-proclaimed vulgarian and motormouth) C. Spike Trotman got to tweeting about “one of the most misunderstood genres in European, specifically Flemish, art”….

Vanitas is Latin for empty, futile, WORTHLESS. And it’s a description of your SHORT AND POINTLESS MORTAL LIFE. Skulls, snuffed and short candles, wilting flowers, emptying hourglasses, fragile soap bubbles, toppled glasses. The symbolism is still clear, centuries later.

Portraits can also be vanitas paintings, especially when they depict a beautiful, young figure – they stand as a warning against conceit and a reminder that all humans age and die. See Caravaggio’s Boy with a Basket of Fruit, in which an idealized male figure is juxtaposed against overripe and rotten fruit. A more hopeful interpretation would be that vanitas paintings warn the viewer of death, but in doing so urge the viewer to live, to enjoy, while they can.

Memento mori influenced many other artistic mediums, from the tradition of the Requiem to many literary works such as Hamlet and The Picture of Dorian Gray. Its themes have been incorporated into the decorative arts as well, in both aesthetic and symbolic ways.

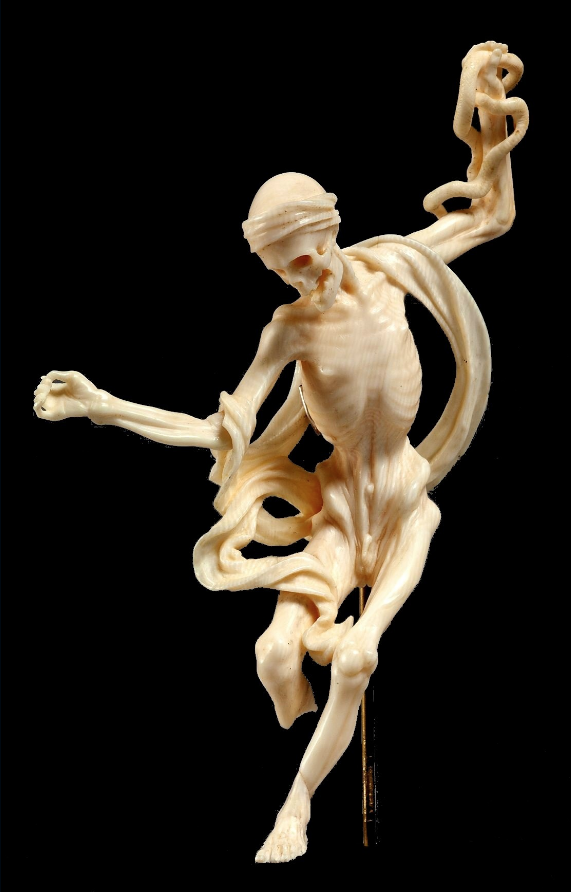

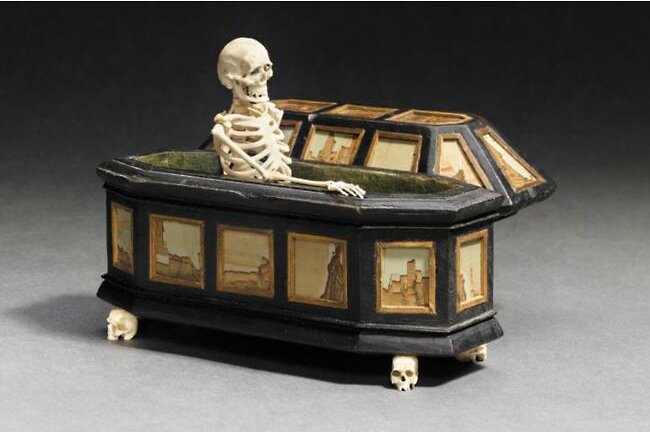

Art objects such as this 16th century Italian carving of a man in a coffin would be owned by private citizens as objects of contemplation, the same way individuals owned small religious icons. The dead man in the carving is in no way idealized, his body is shown unflinchingly in the process of decomposition, complete with worms in his stomach.

From around the same time period is this German rosary, which features eight ivory beads carved to show, on one side, rich, healthy German people. Flip the rosary over the same figures as skeletons. Like the carved coffin, this rosary would have been kept by an individual as an object of prayer and meditation.

Perhaps one of the most striking manifestations of memento mori in art is the incorporation of photography or sculpture into funerary rituals. Typically reserved for politicians, artists, or other personages, a death mask is a plaster cast made of the face of the deceased. In addition to being a memento mori, they also served a practical purpose before the widespread availability of photography; the facial features of unidentified bodies were sometimes preserved by creating death masks so that relatives of the deceased could recognise them if they were seeking a missing person.

The practice began in Europe during the Middle Ages, though it could be traced back to the funeral masks of ancient Egypt. Death masks would be used to strengthen the spirit of the mummy and guard the soul from evil spirits on its way to the afterworld. They could also be use to create portraits or sculptures of important people, or could be kept by the deceased’s family. Other popular methods of documenting the death of a person included commissioning an artist to paint their death bed, but this, like the death mask, was reserved for the upper classes and the well-known.

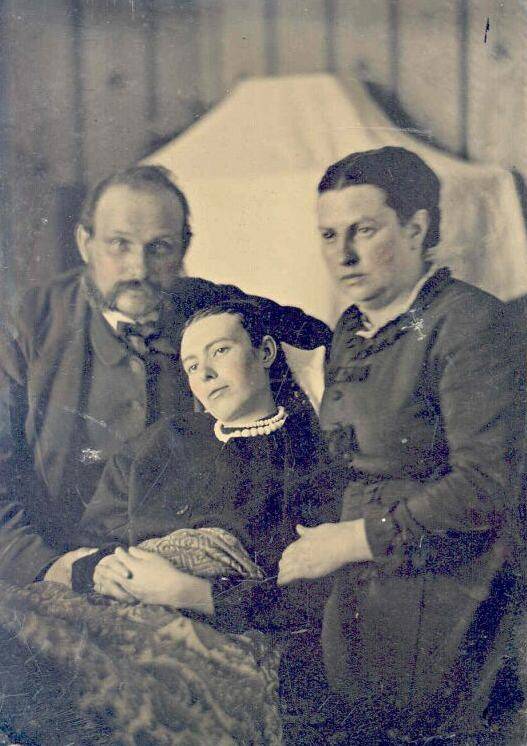

The tradition of preserving images of the dead would be the precursor to a more unsettling practice that emerged with the advent of photography. In fact, due to the slow shutter speed of early cameras, one might say that a 19th century portrait photographer’s ideal subject was a deceased one. Unable to move, flinch or blink, a dead person was often easier to capture than a living one. And during Victorian times, when mortality rates were so high, particularly amongst children and infants with the rampant spread of disease, post-mortem photography became big business.

To Victorians, “memento mori” meant that the dead should be honored and their mortality never forgotten by the living. Death photos were used to memorialise their departed loved ones and were a great source of comfort, similar to Victorian Hair Shrines.

Mourning portraits became as common and accepted as our modern equivalent of a family portrait. Some families even requested their deceased relative be photographed with their eyes open – so if you ever come across an unusually sharp daguerreotype portrait, chances are, it might just be a memento mori.

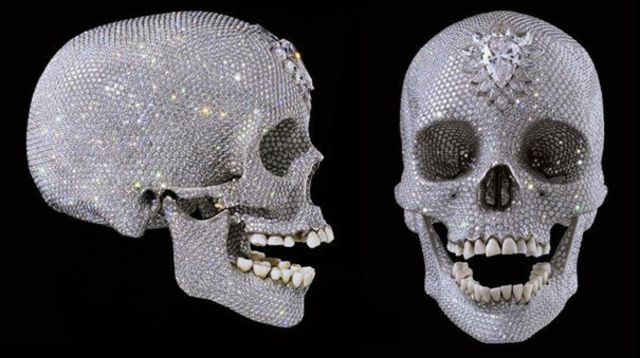

A quick survey of contemporary culture will show you that memento mori is still everywhere. Skulls abound in modern art, Alexander McQueen made them high fashion, and don’t we even have a skull emoji at our fingertips? Yet though we’re exposed to memento mori in art, it doesn’t seem to be as laden with symbolism or provoke the same contemplative reactions as was originally designed to.

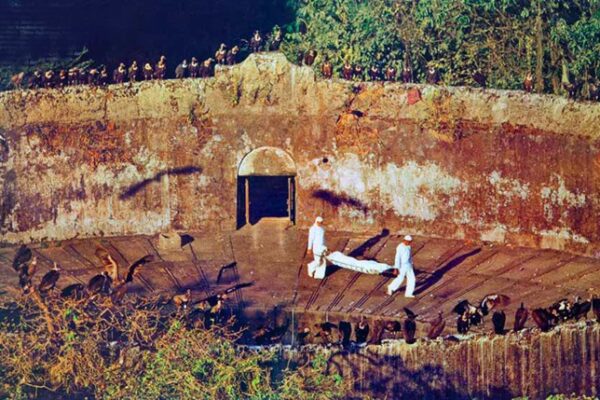

Perhaps we have simply become desensitised to fabricated images in a way that the people of earlier eras weren’t. More importantly, the time we live in today is far more uncomfortable with death than earlier periods. Out of necessity, people living in eras of war and plague had to grapple with certain aspects of life and (most importantly) death in a way that feels foreign to us today. Our funerary practices have drastically changed as well. The process of embalming began during the American Civil War (to preserve the bodies of Union soldiers for the journey North), which lead to the rise of the funeral home and the appealing option to separate ourselves from death by calling in a professional. Before, end-of-life rituals were typically done at home by the family of the deceased.

This shift in traditions has ultimately increased our discomfort with death, both in a literal and a physical way. It is a mistake to dismiss the memento mori, and see it only as something creepy and upsetting to bring up around Halloween. Instead, we should take these references to death as the ancients did, as reminders to live. So take a stroll through a museum sometime soon and look out for the memento mori.