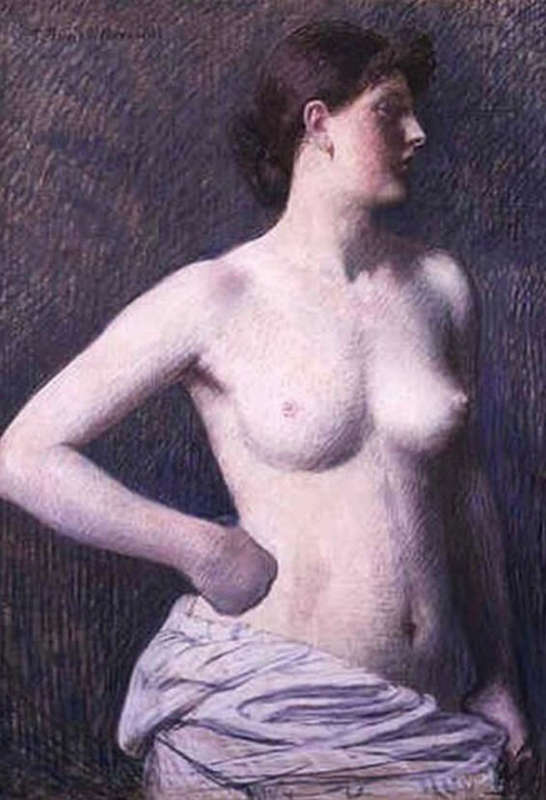

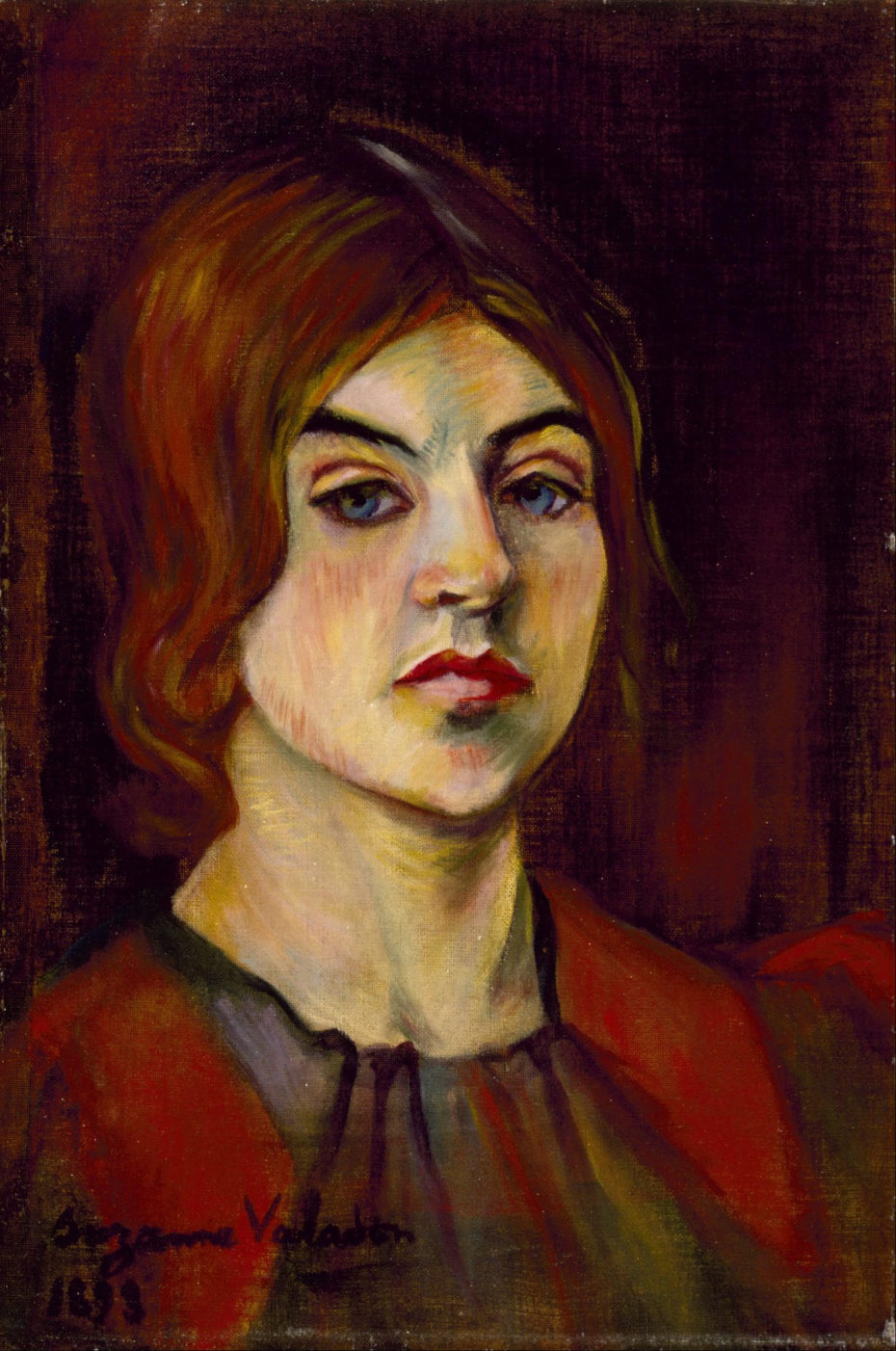

Name a post-Impressionist woman painter and most people would draw a blank. Or they would cast their mind back to Mary Cassat or Berthe Morisot and their pastel domestic scenes. Few know of Suzanne Valadon, who shocked the turn-of-the-century art world with her boldly outlined nudes. A circus performer, single teenage mother, and art model turned painter, Valadon blazed a unique path through the Belle Epoque, and created a body of work as vivid and honest as her life.

Unlike Cassat or Morisot, Valadon came from abject poverty. She was born Marie-Clementine Valadon in 1865 in Bessines-sur-Garteme, a village in the rural heart of France. Her mother, Madeleine, was a widowed linen maid, who already had a daughter. Despite village gossip, Madeleine refused to name Valadon’s father. She struggled to raise the two girls by herself, and then in 1870, decided to take her family to Paris in search of greater opportunity.

Her timing couldn’t have been worse. In July that year, France declared war on Prussia. By September, the Prussians had surrounded the city and were starving the French into surrender. After a month without provisions, Parisians began to eat dogs, cats, rats, and finally, all the animals in the zoo (true story). The armistice in 1871 led to the Paris Commune, a short-lived takeover by the working-class. In the midst of all this revolutionary fervor, Valadon’s family found a home in Montmartre.

Valadon was enrolled in a charitable school at St. Vincent de Paul. An unruly child, she was dismissed at the age of 11 and began a series of menial jobs. Seamstress, dishwasher, vendor at a fruit and vegetable stall, maker of funeral wreaths. At the age of 15, she found work at Le Cirque Molier, a private circus with aristocratic guest performers that was the height of fashion in Paris. For six months, Valadon stood on horses galloping around a ring and balanced on a tightrope. Then, while rehearsing a trapeze routine, she fell and seriously injured her back.

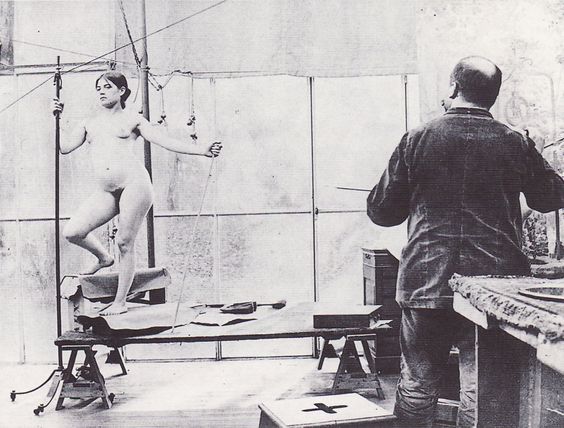

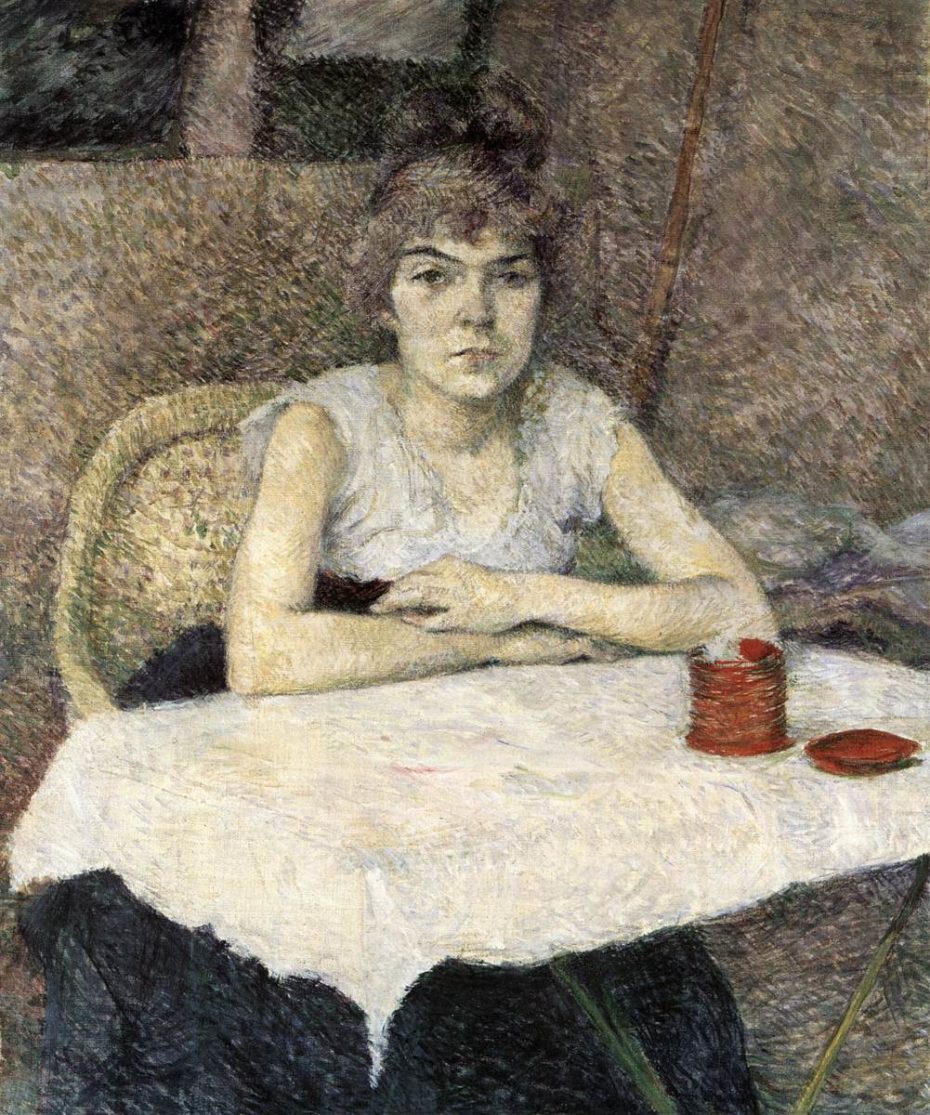

Unable to return to the circus after recovering from her injury, Valadon found work as an art model. The legend is that she was sent by her mother to deliver a basket of laundry and caught the eye of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, who was searching for someone to pose for his allegorical paintings. Calling herself Maria, she quickly became a sought-after model, posing for a who’s who of the artists flocking to Montmartre.

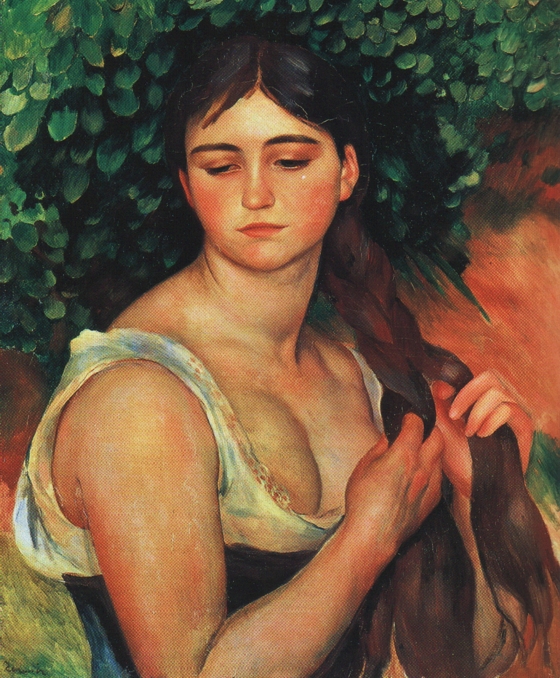

From Puvis de Chavanne’s symbolist allegories, she went on to pose for Gustav Wertheimer’s Kiss of the Siren paintings, and drawings by renowned illustrator Jean-Louis Forain. Most famously, she became a regular model for Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

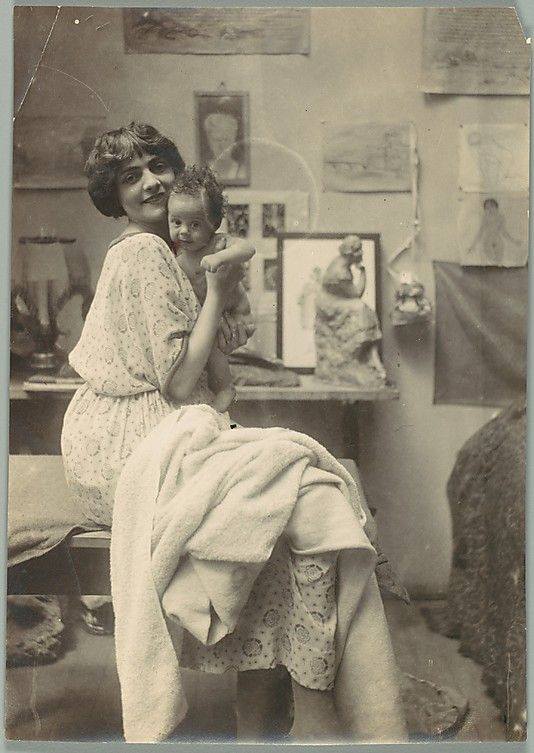

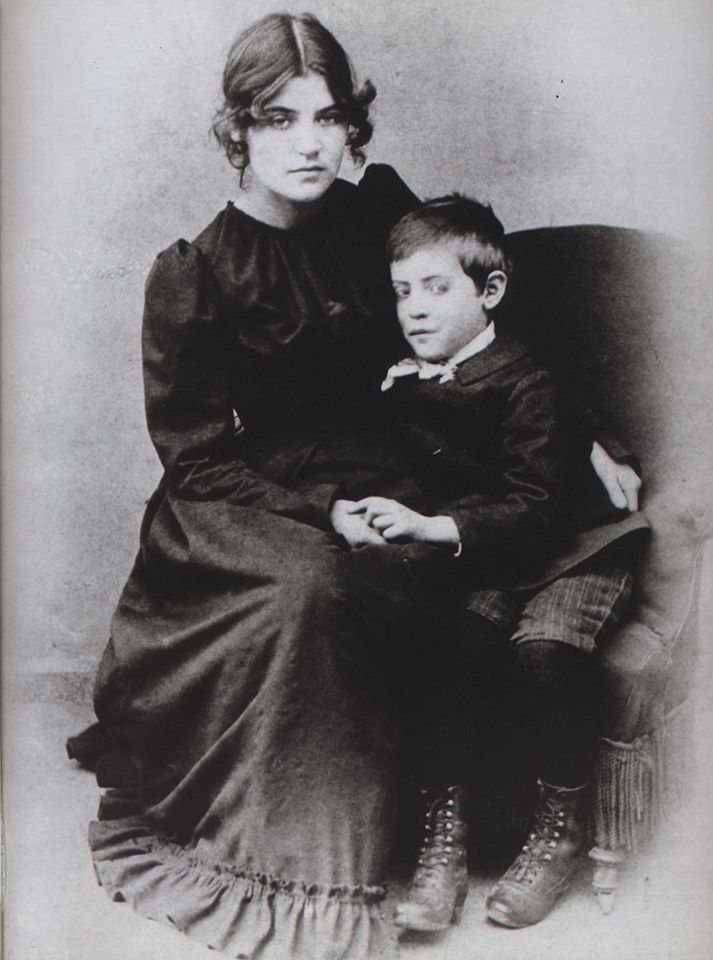

Just after starting to work for Renoir in 1883, Valadon became pregnant. Following in her mother’s footsteps, she refused to name the father. Gossips speculated whether the father was Puvis de Chavannes, Renoir, the Spanish Impressionist Miguel Utrillo, or perhaps an accountant by the name of Adrien Bouissy, who may have date raped her. Valadon just shrugged, “I’ve never been able to decide.” Her son was born in December and she named him Maurice. Soon, she was back to the art studio, leaving Maurice in the care of her own mother Madeleine.

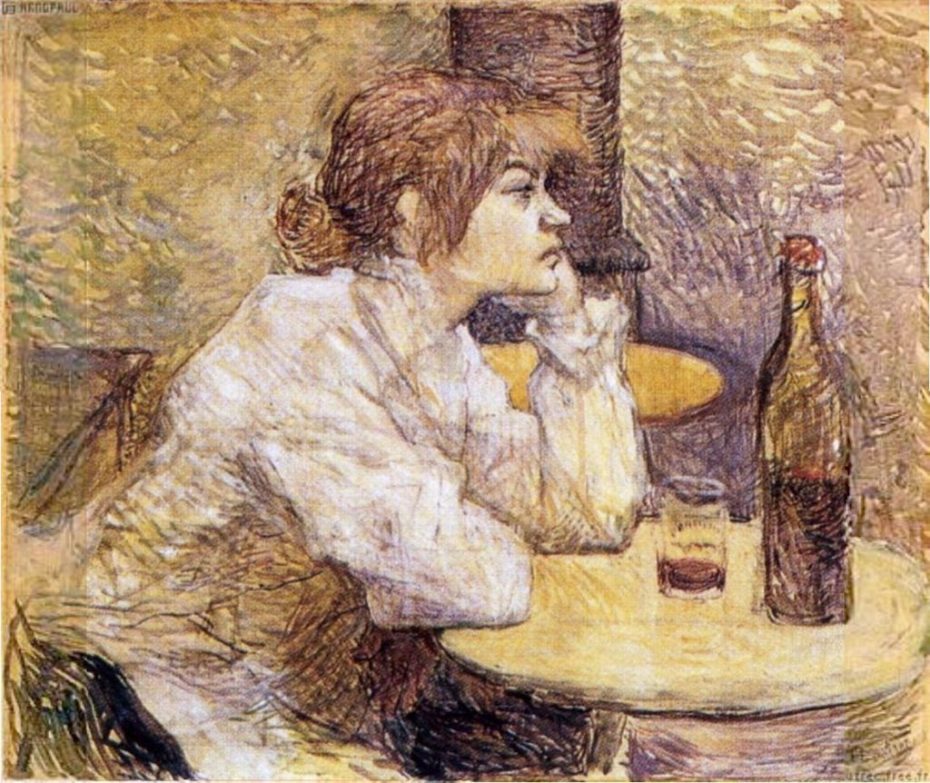

Valadon became acquainted with Henri Toulouse-Lautrec in 1887. The scion of one of the noblest houses in France, Toulouse-Lautrec suffered from a mysterious disability that was probably the result of inbreeding. Though his upper torso was that of a grown man’s, his legs had stopped growing after he broke both hips at the age of fourteen. He shuffled awkwardly up the hill of Montmartre with a cane and struggled with facial deformities. Despite this – or perhaps because of this – he was an incorrigible bon vivant, with the means to experience all the glittering nightlife of fin de siècle Paris. Valadon became the unofficial hostess of his lavish dinner parties. She also received her artist name from Toulouse-Lautrec. He christened her Suzanne, after the Biblical story Susanna and the Elders, because she often posed for older men.

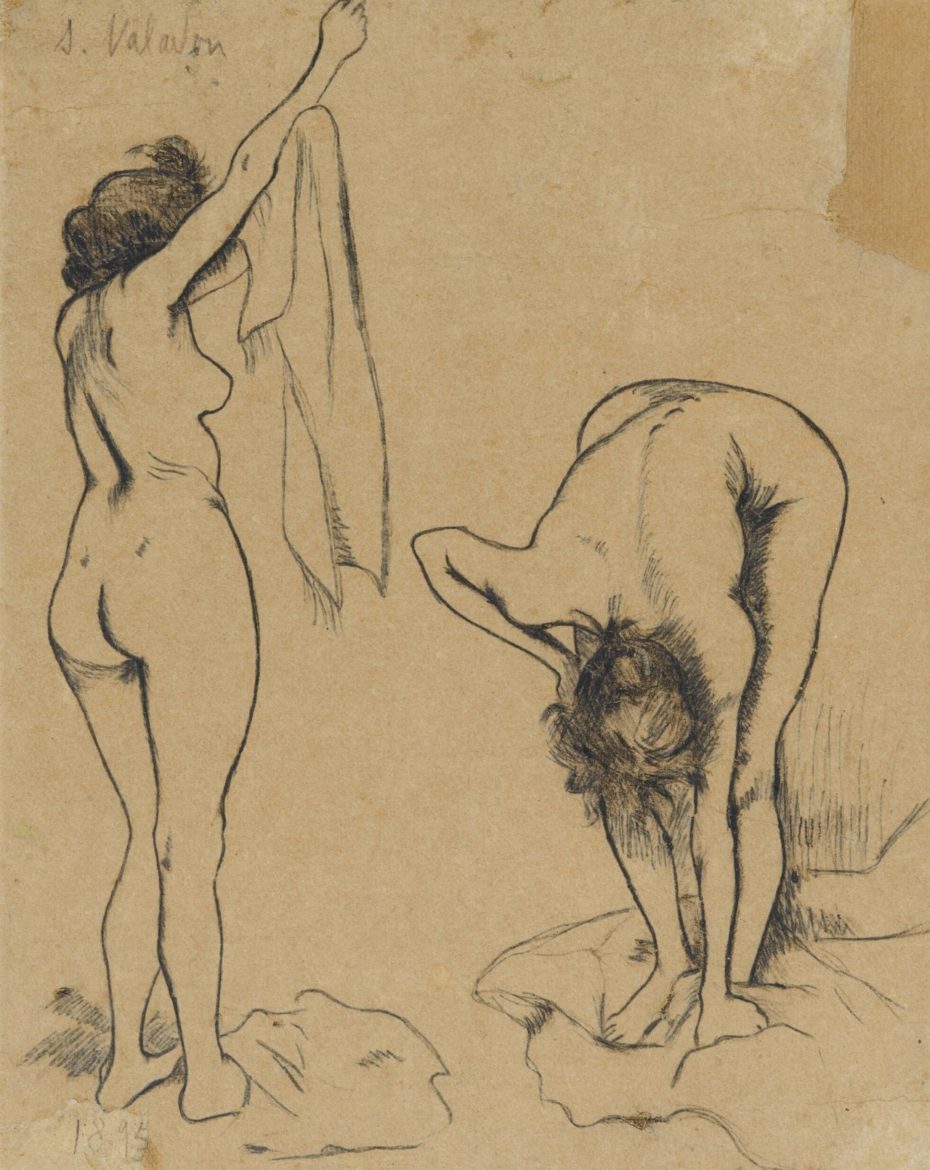

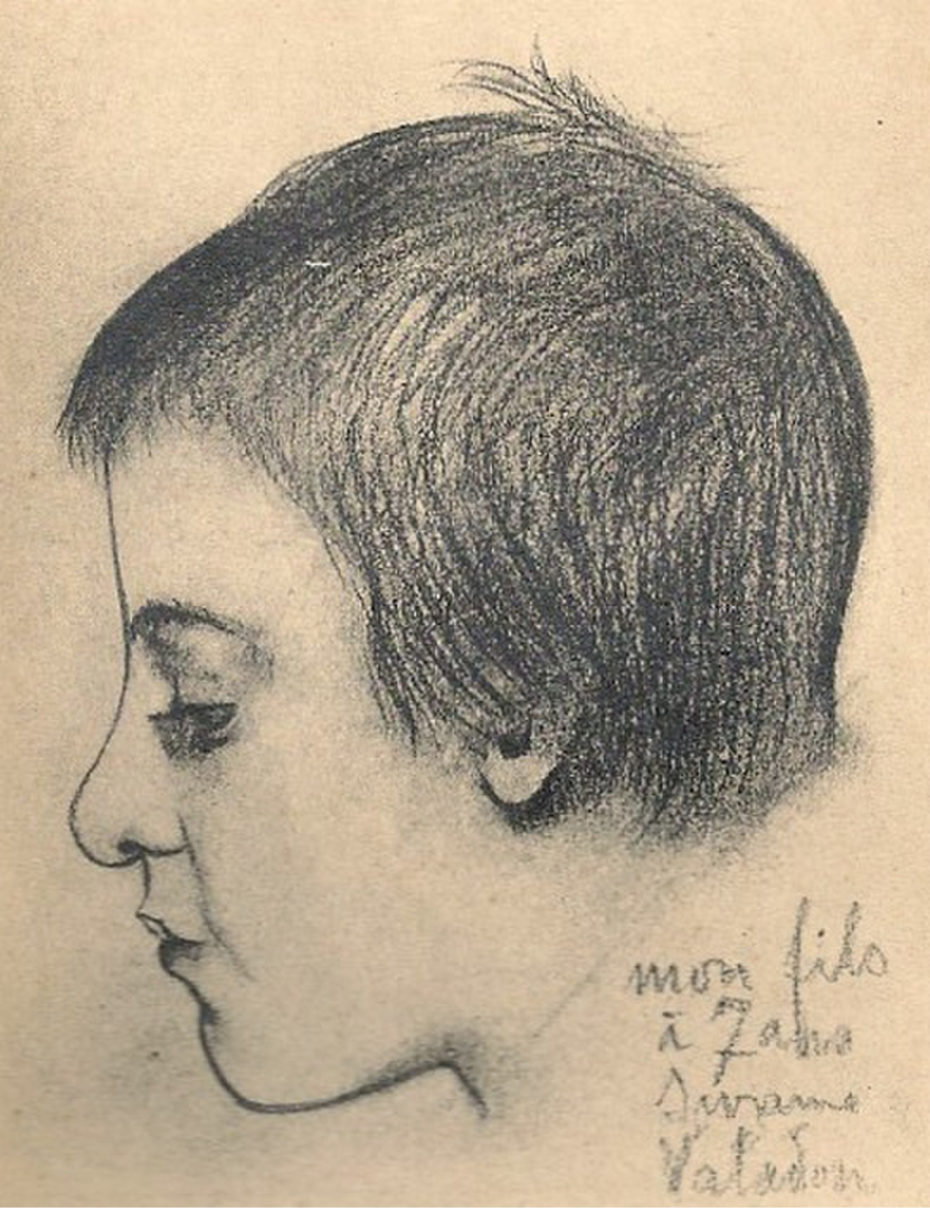

Valadon had always drawn, but without the means to attend a conservatory, she kept her sketches to herself. After her son was born, however, she began to take her art more seriously. Toulouse-Lautrec was one of the first to appreciate her work. He bought a few of her drawings and hung them in his studio, chortling with glee when astonished visitors learned that they were made by a self-taught woman.

By 1890, Valadon had found an artistic mentor in Edgar Degas. Impressed with her skill in line drawings, he showed her work to collectors and suggested that she learn soft ground etching. In 1894, he suggested that she submit her work to the Salon de la Societé Nationale des Beaux-Arts, the most prestigious exhibition hall in Paris. It was unheard of for the Societé to show the work of an untrained lower-class woman, but with the combined recommendations of Degas and sculptor Paul-Albert Bartholomé, five of Valadon’s drawings were accepted.

In the meantime, Valadon struggled to balance her burgeoning artistic career, her volatile love life, and her responsibilities as a mother. By the time Maurice was five, it was clear that there was something wrong with him. Unusually pensive and shy, he would suddenly erupt in unexplained fits and throw things around the room. Valadon worried that he needed a father figure and approached Miguel Utrillo, who agreed to give Maurice his last name and legally recognize him as his son. Valadon, however, continued to be a single mother with Utrillo contributing little to Maurice’s upbringing.

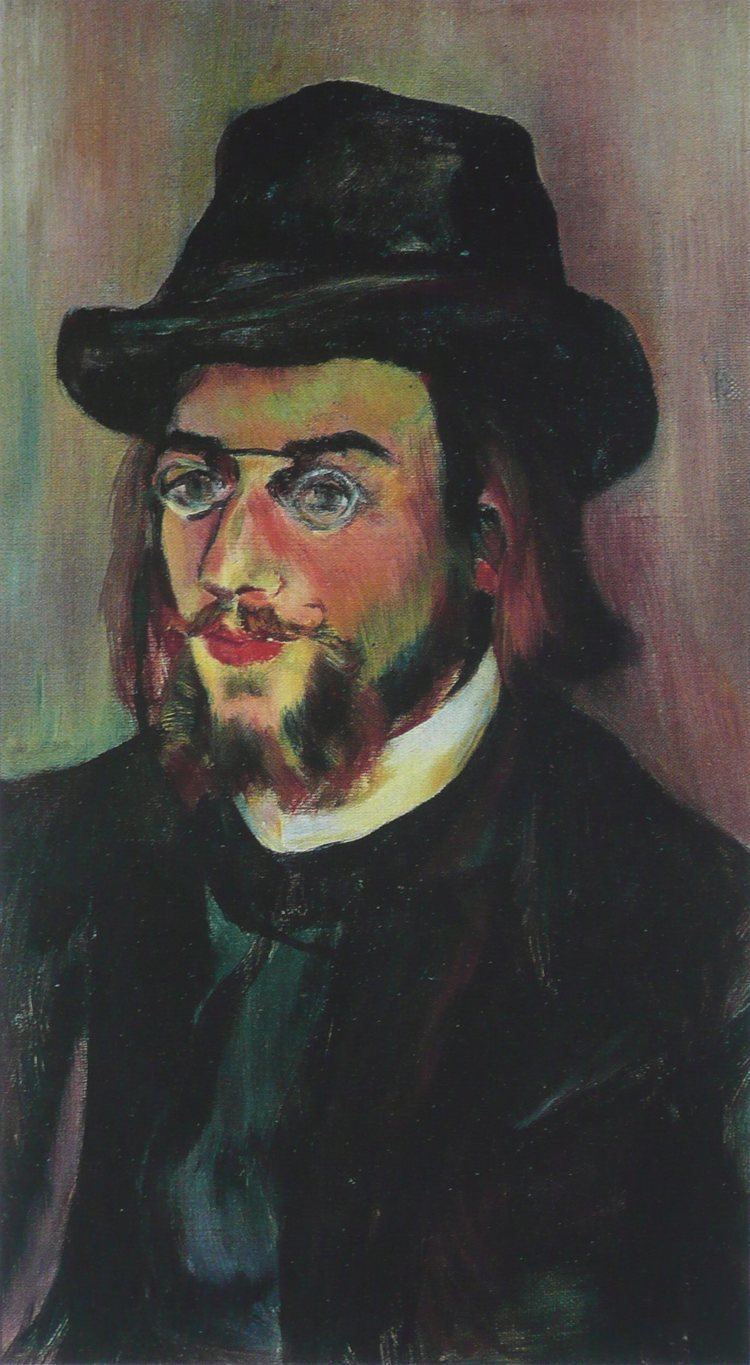

It was Utrillo who introduced Valadon to the eccentric Erik Satie, whose experimental compositions were challenging the music world. Sparks flew and they quickly fell into an intense relationship, with Satie allegedly proposing on their first night together. Valadon refused, laughing that there wasn’t a priest to be found at 3am, but they moved in together. He modelled for her first oil painting and in turn, she inspired a few quirky musical compositions. But with Satie so demanding and possessive, Valadon felt stifled in the relationship. She finally left and he never went out with another woman in his life.

Valadon rebounded from Satie in the arms of Paul Mousis, a well-off businessman. He set her up in a studio and took her entire family under his wing. For the first time, Valadon began to enjoy an upper middle class life. Mousis convinced her to move to Pierrefitte, a suburban town 20 minutes away from the Gare du Nord on the newly created train line. Living in a beautiful house with a garden, and commuting to her Montmartre studio during the week, Valadon was in bourgeois heaven. In 1895, she made it legal and married Mousis.

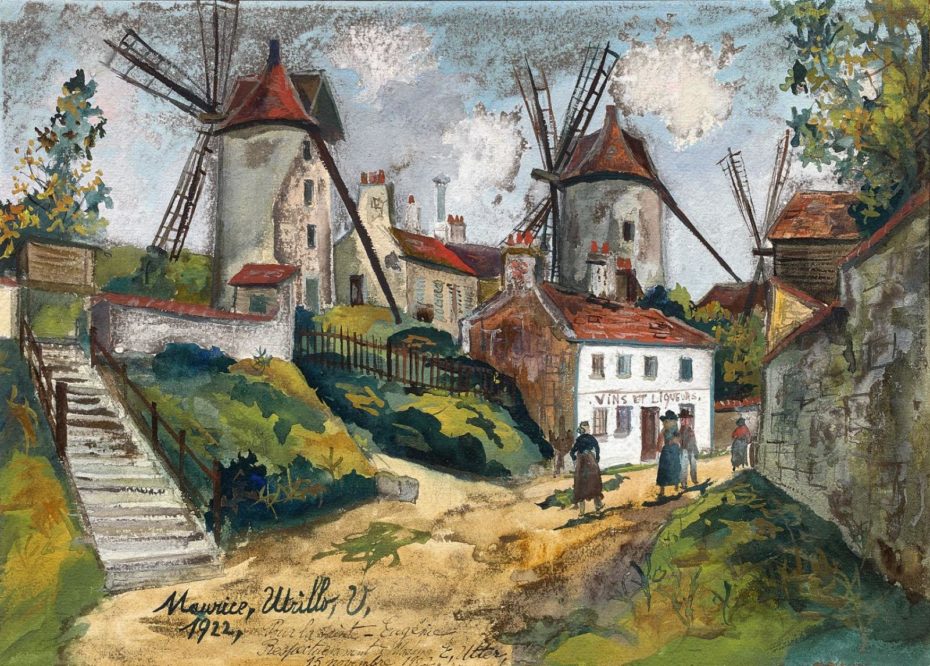

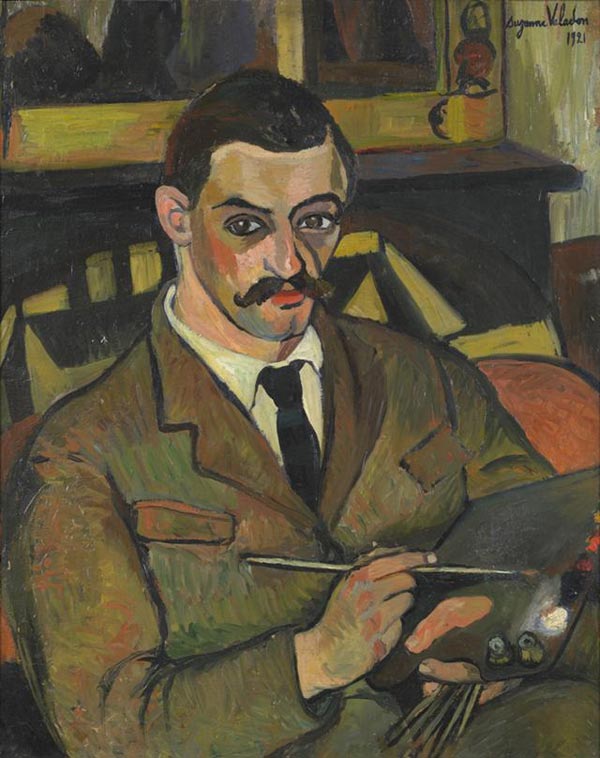

The problem was that her son Maurice was miserable in the suburbs and acted out in unusual ways. By the time he was fifteen, he was so regularly medicating himself with alcohol, that he had become a blackout drunk. Mousis tried to help by finding his stepson work, but Maurice was incapable of keeping a job. Finally, he got so violent that Valadon agreed to commit him to a hospital. After he was released, a doctor suggested that Valadon teach him painting. Maurice turned out to be an apt pupil with a style vastly different from his mother’s. He would later become quite renowned for his dreamlike Montmartre street scenes.

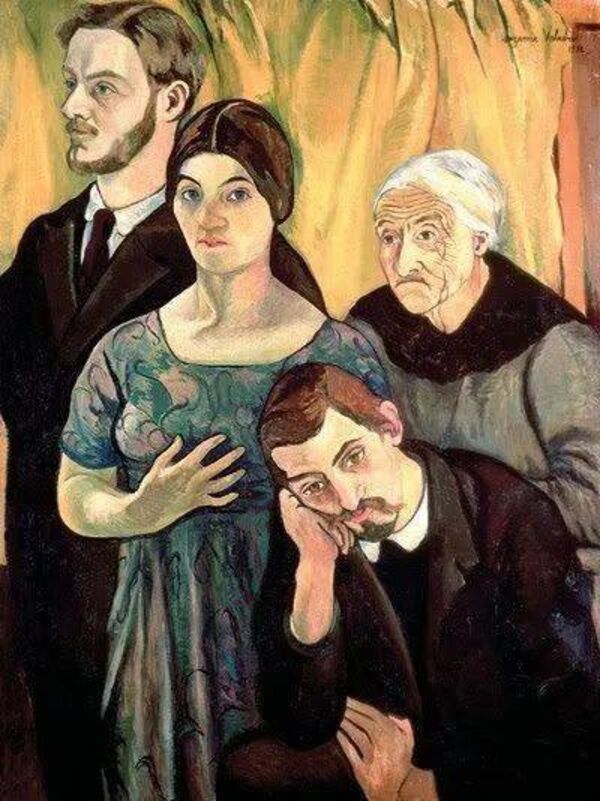

It was Maurice’s combination of painting and alcoholism that led to the end of Valadon’s bourgeois period. He was out in the fields painting one day and got so drunk that he could barely put one foot in front of the other. By chance, another painter was out in the fields. His name was André Utter and he became one of Maurice’s only friends after helping him stumble home. Soon, he was also Suzanne’s lover, though they had a twenty year age gap, and he was three years younger than her own son. Valadon left Mousis and moved back to Montmartre, setting up house with Utter, Maurice, and her mother. She painted the four of them together, an unusual blended family, with a woman as the centre of the household.

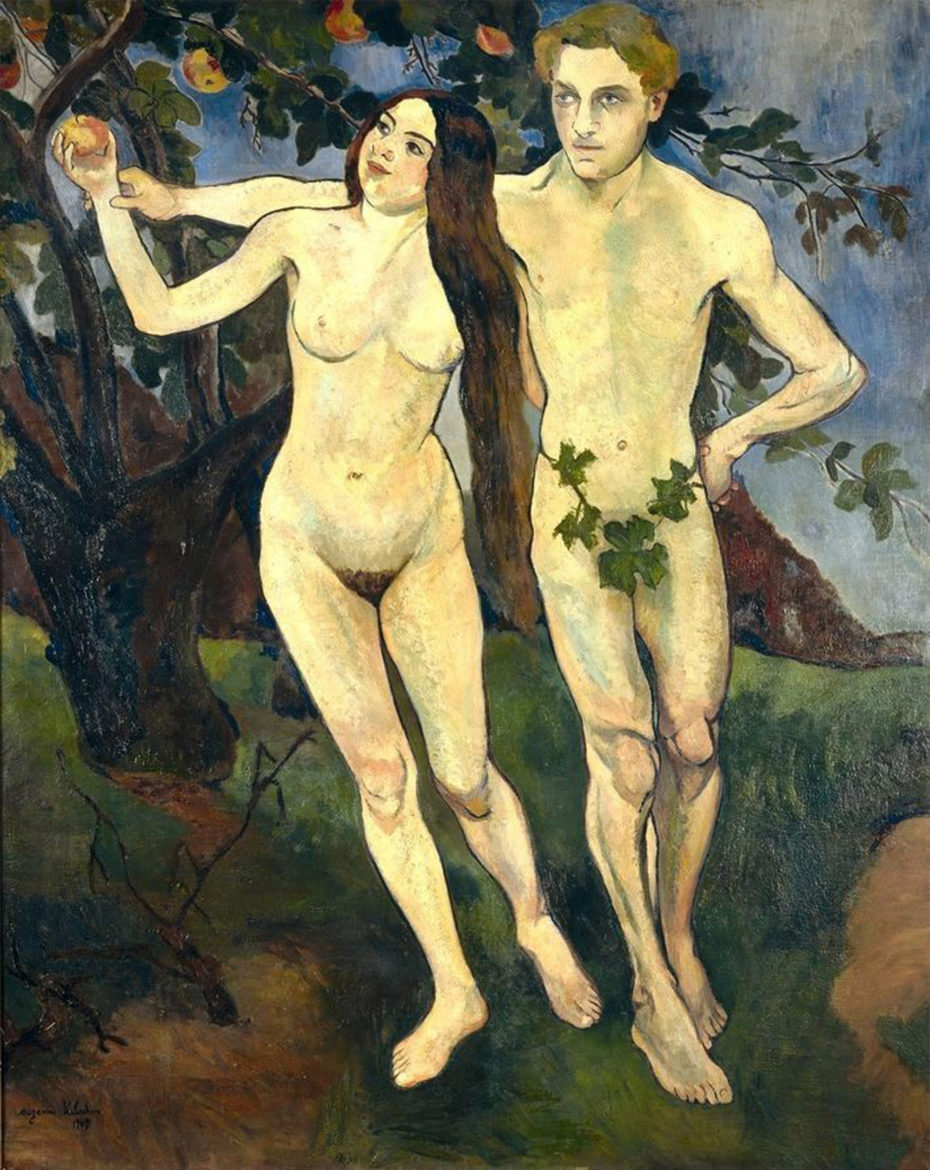

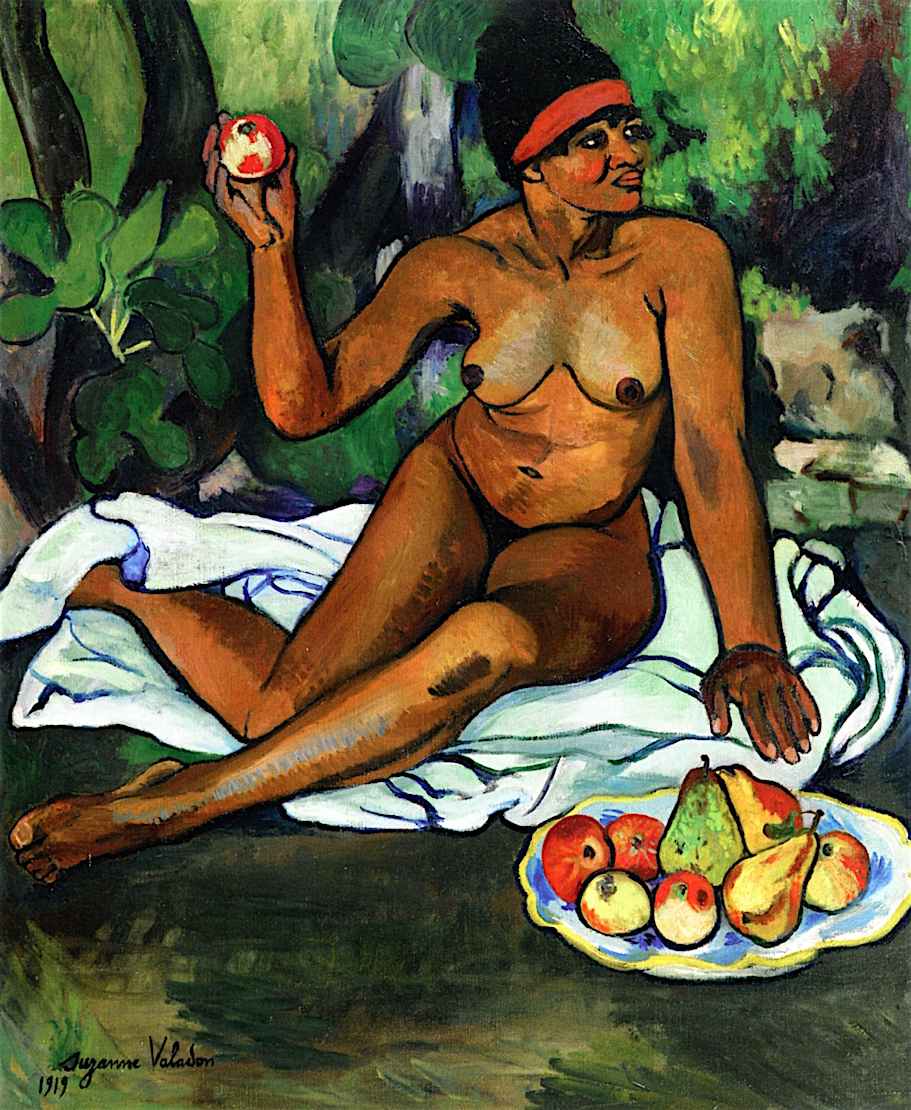

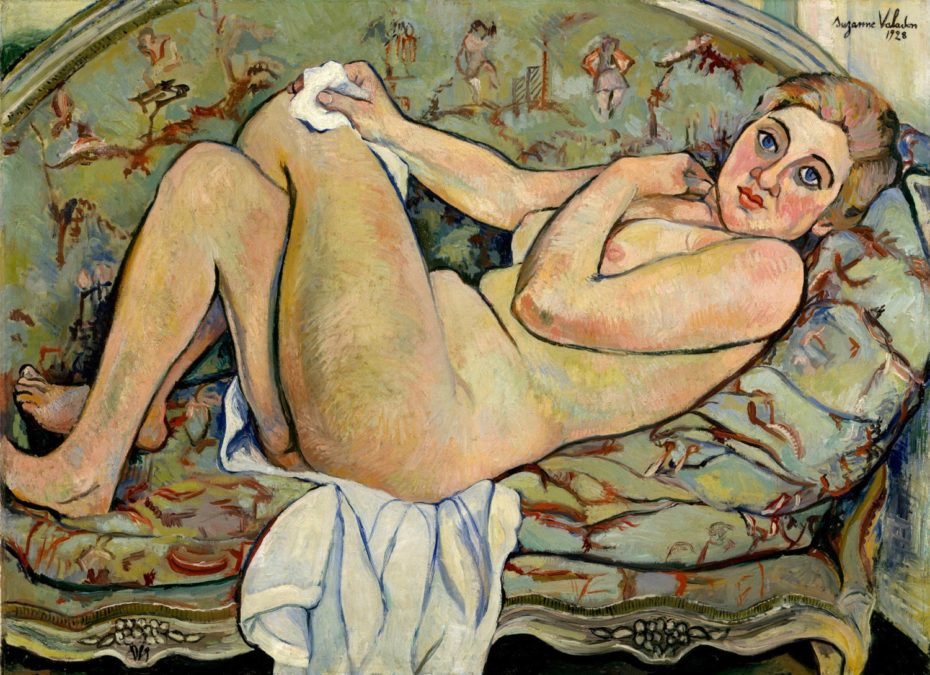

During her time out in the suburbs, Valadon had hardly produced any work and now she immersed herself in her painting. Utter posed nude for her scandalous Adam and Eve, where both Adam and Eve reach for the apple together. The painting was so shocking, she was later forced to add a fig leaf to cover Adam’s genitals (but not Eve’s) so she could exhibit it publicly. Utter was not the only male nude she painted. Her 1914 painting, Casting the Net, features three life-sized nude men, reversing traditional gender roles with Valadon as the voyeur and the three men as objects of lust.

André Utter enlisted in World War I and they married just before he left for the front. He was wounded in 1917 and Valadon moved to Belleville-sur-Saône where he was recovering north of Lyon. That year, the prestigious Parisian gallery Galerie Bernheim-Jeune exhibited work by Valadon, her son Maurice, and her husband André. After the war, when sales of their paintings increased, the gallery offered Valadon and Maurice an annual payment of a million francs for all their future paintings.

This enormous income allowed Valadon to indulge her eccentricities. She took all the neighbourhood children out to the circus one day. On another day, she threw 100 franc bills out of the window for people to pick up. She was notorious for keeping a pet goat in her Montmartre studio and feeding it the sketches that she didn’t like.

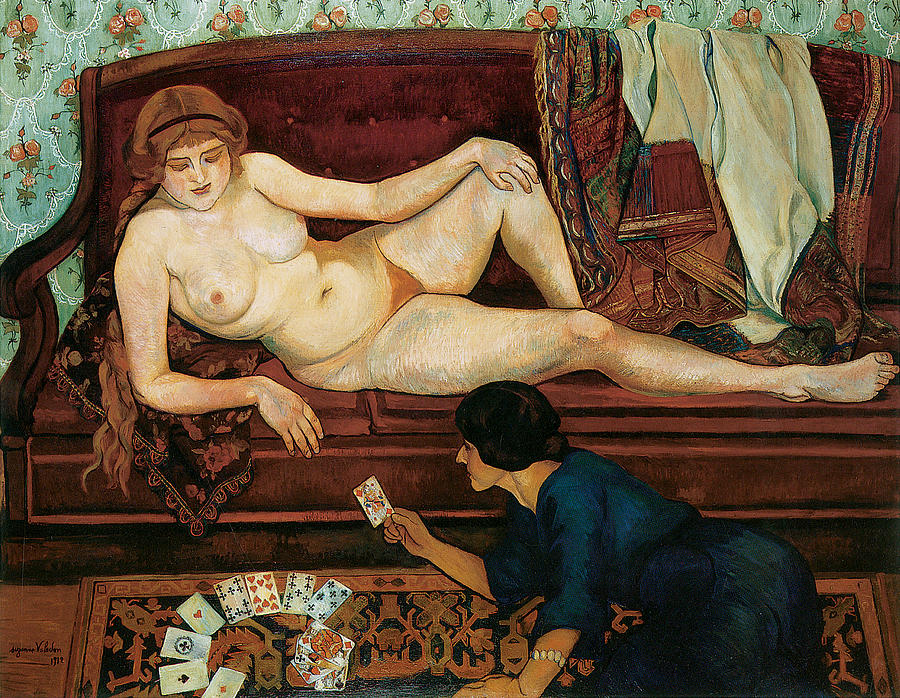

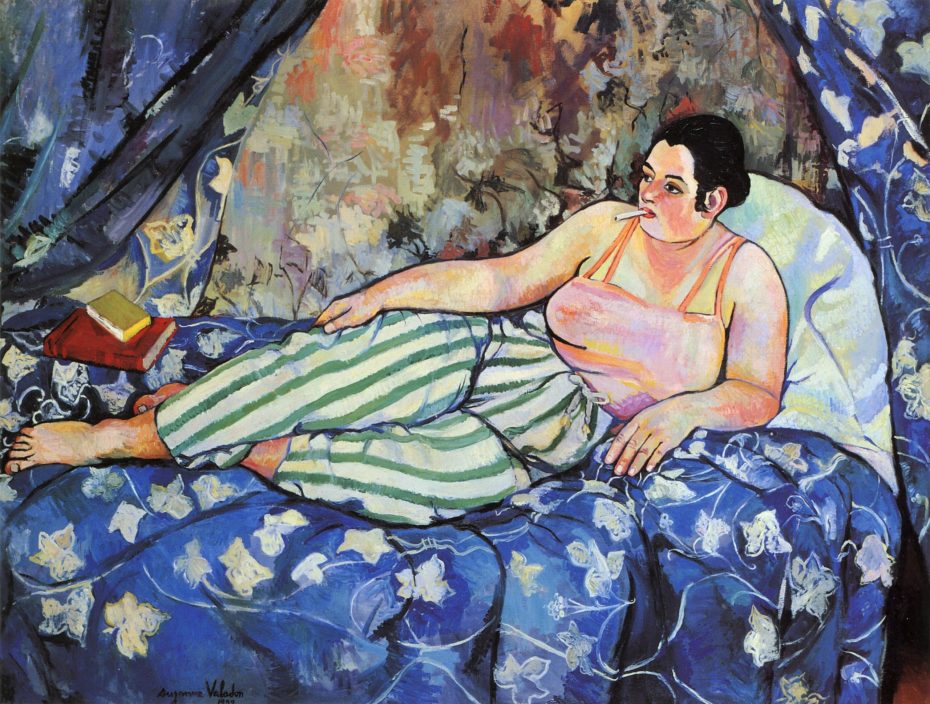

She continued to create bold work that showed women as agents of their own destinies. In one of her most famous paintings, The Blue Room, a woman lounges on a bed in counterpoint to Edouard Manet’s Olympia. Instead of sexual availability and desire, she is perfectly content on her own. Dressed in striped pyjamas with a cigarette dangling from her lip, she doesn’t care what anyone thinks. Instead of a maid bringing her flowers, she has a pile of books in a corner.

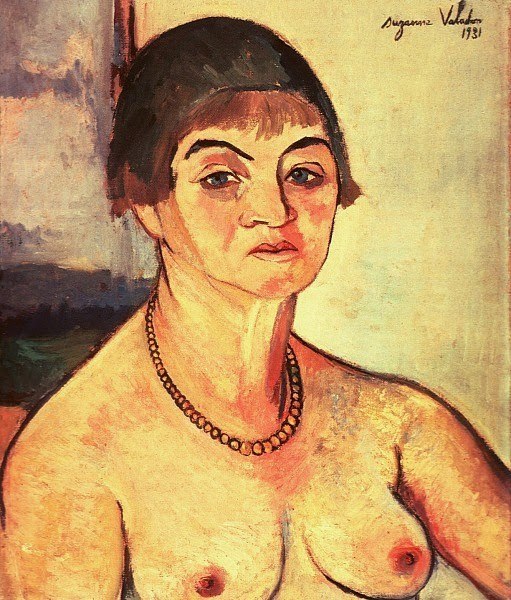

At the age of 67, she painted herself wearing nothing but a necklace, gazing with mixed emotions at all the effects of aging. “I can’t flatter a subject,” she once said. This unflinching honesty is what makes her so unique. Though history has relegated her to Renoir’s model, Maurice’s mother, Toulouse-Lautrec ‘s drinking buddy and Erik Satie’s lover, she stands on her own and should be celebrated as a visionary artist with a pivotal role in history.

The Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia is currently hosting her first major US exhibition until January 2022.

About the Contributor