‘Objectification’ simply doesn’t sit well with our emancipated, liberal 21st century selves; in its simplest form it suggests the degrading of someone to the status of a mere object. Throughout history, the objectification of women, going hand in hand with gender discrimination, body dysmorphic disorders and sexual violence, is a familiar problem we know all too well. But what of male objectification?

Let’s take a few steps back. From our earliest days, the prehistoric man’s role was to not only to take down the mammoth while the womenfolk were hiding with the kids, but also to defend the settlement. The male body was the weapon for defence. Over the years, this ‘body as a weapon’ role has been promoted and revered to the point where it’s idolised. Nature and our evolutionary instincts still opt to assess a potential partner’s first impressions using visual cues such as health, fitness, beauty and displays of strength. But lo and behold, parts of the modern human cortex have somewhat evolved over time and we know now that visual beauty alone is one-dimensional; a purely superficial aesthetic, a judgement devoid of taking into account personality or character.

But where did it all start? Throughout the ages the image of the male body has been hijacked to serve a multitude of cultural and political purposes, from security to sexuality. In the process it has picked up a bunch of political and social baggage. Way back at the dawn of European civilization, in the 15th century CBE, we see playful images of athletic Mediterranean Minoan traders preserved on their pottery decoration and wall paintings, celebrating both the bull jumping rituals and their own beauty. Researcher Irena Lexová notes that in ancient Egyptian dance, male dancers would wear were collars around their necks. Dancing often took place in the nude, except for the occasional small fringed skirt or tunic, and only featured one gender at a time, with little to no evidence of males and females dancing together. Western literature has often depicted Cleopatra as a polyamorous, pleasure-seeking man eater who made men fight with tigers to feed her lust, but her fanciful erotic adventures and alleged sexual deviancy perhaps speak more to her enemies’ agenda.

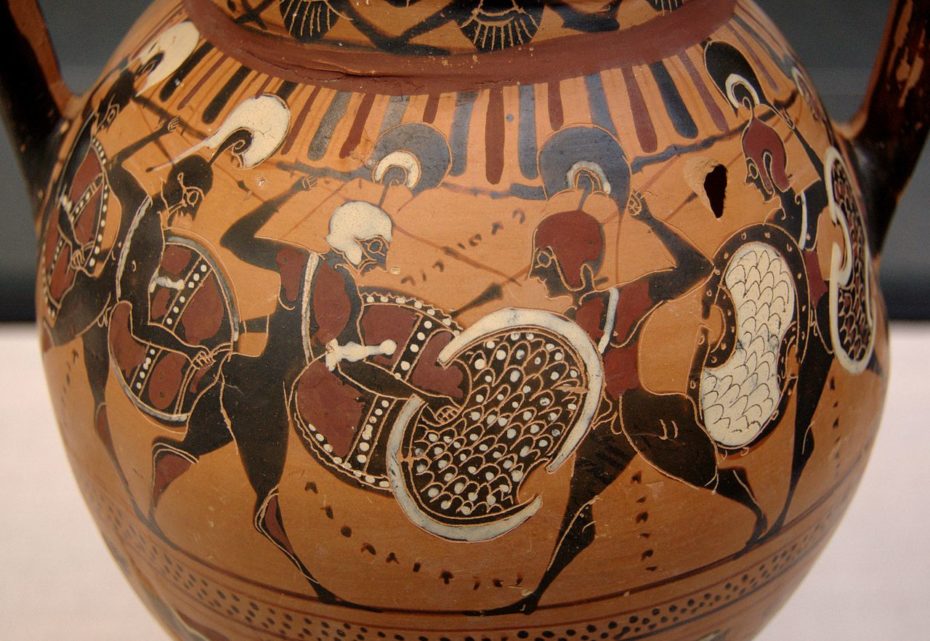

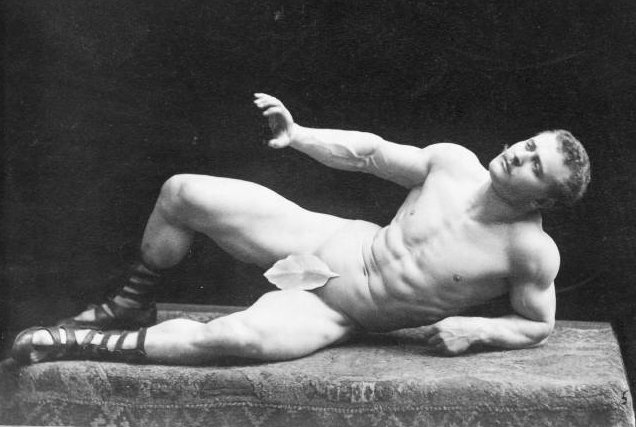

The ancient Greeks, particularly the Spartans appropriated the male body for the public to celebrate its success in war, where physique, fitness and battle ability were essentials for the security of the state. Sparta was a small ancient Greek state, run entirely on military lines, which had ensured its survival for centuries. The Spartan warriors were legendary and the foundation of folklore throughout the ages was aptly depicted in the rather fleshy Hollywood movie 300.

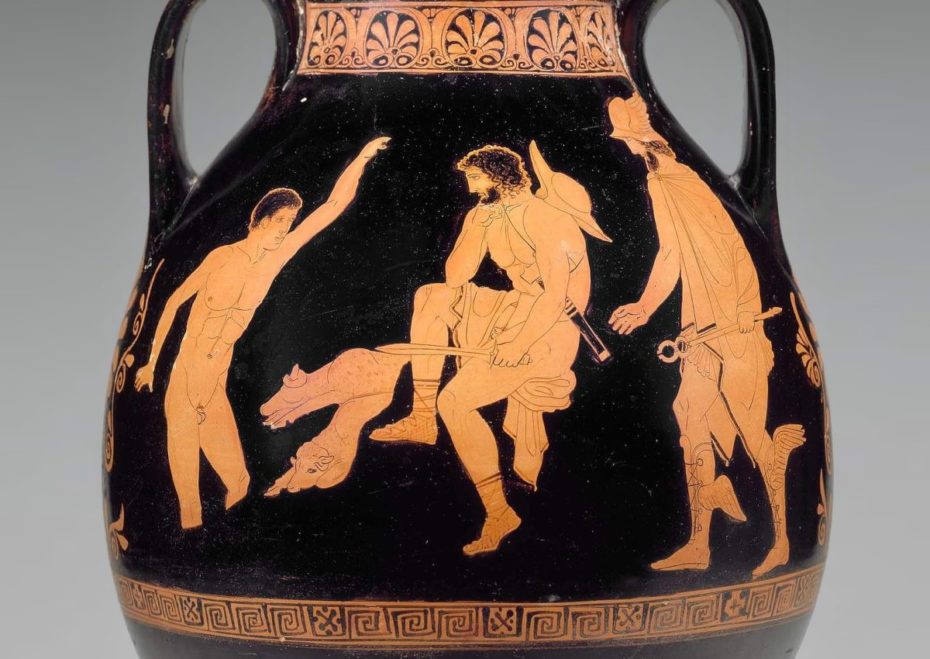

In the age of the Athenians and Alexander the Great, society was a little more rounded than that of the militaristic Spartans; games, music, dance, sculpture, philosophy and mathematics were all strongly valued and promoted in this culture, but the objectification of the male body was taken to new heights. Mostly naked, the Classical Greek male body evolved into a flawless realism and subsequently into godlike perfection. This was clearly a demonstration of the abilities of the sculptor, but without a shadow of a doubt also served to celebrate intellectual superiority of Classical Greek culture and its male protagonists.

Homosexuality and pederasty in ancient Athens are of course well-documented. In his 1997 study Art, desire, and the body in ancient Greece, archeological scholar, Andrew Stewart interprets much of the male nudity in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods as imagery aimed at producing homosexual desire. The naked and half-naked youths of the Parthenon frieze? “Deftly inserted to engage and arouse the citizen spectator,” he says, while arguing that the majority of Classical Greek and Roman art was created with the intent of appealing almost exclusively to the male gaze. Other historians argue however that women were also avid consumers of erotic art, particularly pottery, and that nude vase painting itself enjoyed both male and female audiences.

Seeing themselves as the intellectual and military successor to the Classical Greeks, the Romans rebadged and reused Greek iconography throughout the empire. Rome followed the model of the male-dominated society promoted and celebrated through self-representation, creating more dramatic interpretations and renditions of god-like male perfection for public consumption. The all-powerful empire transformed its leaders into gods, who were of course, shown to the public as bodily perfect and beautiful, there to be idolised and worshipped. The self-indulgent Roman lifestyle revelled in a frenzy of hedonistic fleshy festivities and bloody intrigues. Their lavish bath houses, spectacular games arenas, opulent theatres and public forums were all adorned and dripping with with sexually charged imagery, mostly of the heroic male.

The Roman Empire, with all its excesses had lost its way in the 5th century CE and retreated to Byzantium. The idealized warrior-god-male was passé, redundant and even outlawed. Instead saints and martyrs lined the walls of churches, clad head to toe in religious habits, waving bibles and crosses and the new message was about the frailty of humanity. In the ultimate age of prudence, the arts world was turned on its head – no more realism, no more flesh, no more titillation – only simple mosaics with a pious message for the coming centuries.

With the Renaissance in the 15th century there was a rediscovery of the idealistic imagery and arts of the ancient world of the pagan Greeks and Romans. The Catholic Church saw the advantage of using Classical Greek and Roman iconography as a means of permanently establishing and broadcasting its authority over a rapidly changing world. Artists, patrons and the consuming public were also quite happy to see this new and exotic subject matter take the spotlight in after centuries of dreary religious iconography.

Artistic production exploded, filling churches, palaces and city squares across Europe with neo-classical icons, mostly naked humans packaged in both Christian and pagan themes. Under the umbrella of ‘art’ the feast of flesh satisfied many tastes. The range was vast. Take Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s immense Fountain of the Four Rivers in Rome (1651), where four giant naked strong men personified four rivers and Donatello’s intimate and homo erotic sculpture David; voyeuristic and little to do with its biblical title.

This expansive menu for the objectification of flesh in the guise of classical or religious storytelling continued up to the end of the 19th century, which brought forth conflicting Victorian sensibilities and their cultivation of an outward appearance of dignity, restraint and morality. The European powers carved up the world between them, prided themselves on ‘decency’ with no need for public titillation. Yet, the advent of photography and printing lead to the mass production of dark underground publications, saucy postcards and erotic prints, many filled with overtly sexual images of male and female nudity.

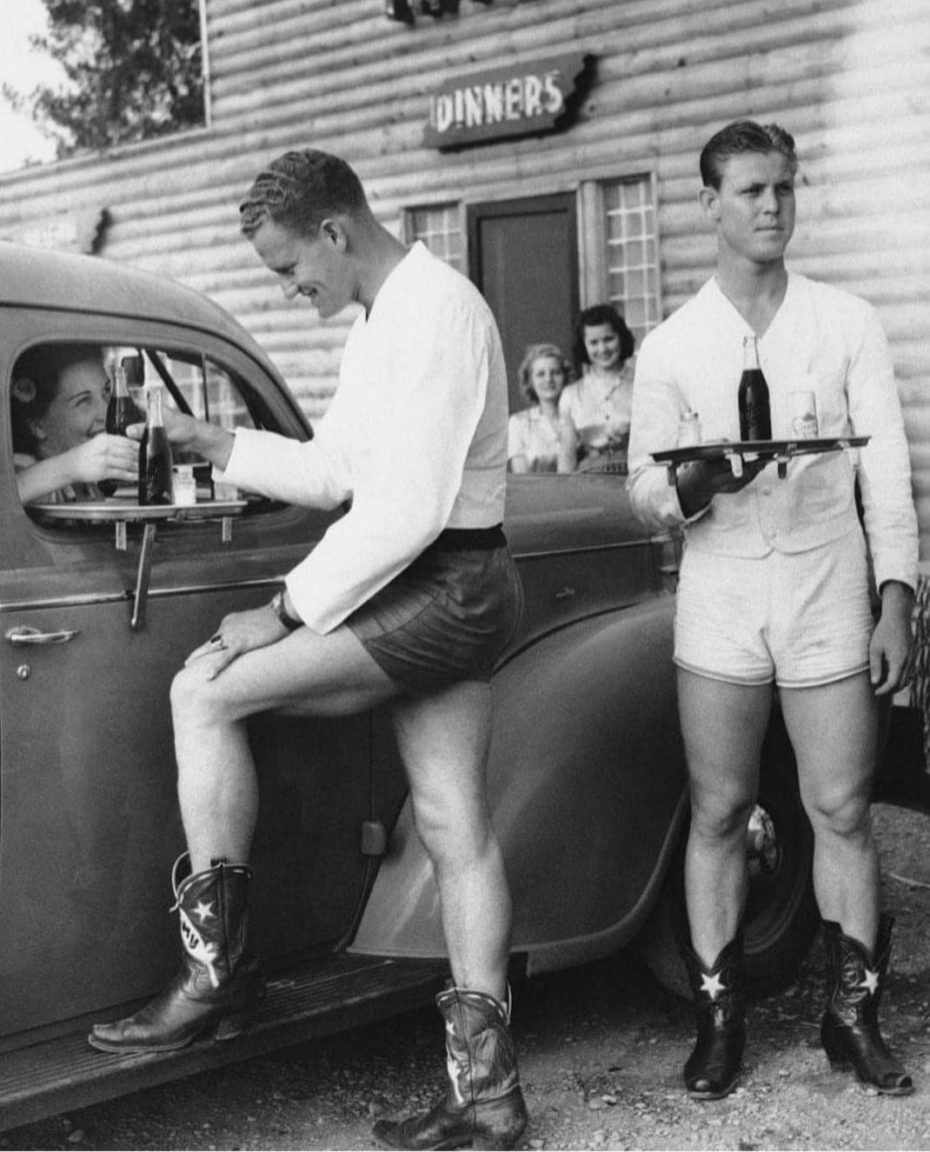

The drive for improved health characterised so many aspects of the 20th Century, not just new hospitals, but diet, living conditions and physical fitness. Casual sport in the 1930s grew from a frivolous pastime to becoming a lifestyle choice to stay fit and healthy. The media perpetuated the body beautiful myth (and with that, objectification) to sell all aspects of sport, advertising, attendance and equipment, playing on aspiration but also on fear of missing out.

Like in the world of sport, early cinema relied on stylish male actors to captivate its female audiences. Fully dressed, fashionable and suave male leads in the 1920’s were offered as the perfect gentlemen. Rudolph Valentino became Hollywood’s first sex symbol but an article in a magazine calling him “flop ears” sent him to the plastic surgeon to have his ears pinned back. In Harrison Pope’s 2003 book, The Adonis Complex, (in reference to the character in Greek mythology known for his beauty and masculinity), the author suggests that male objectification is largely behind a new phenomenon that drives men to become obsessed with their looks and develop related health disorders.

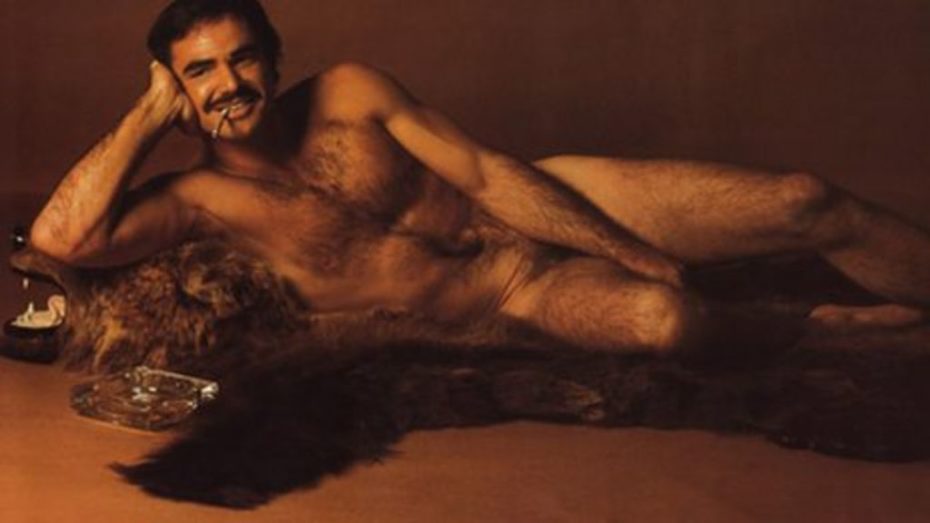

Pope argues that men are just as vulnerable to the pressures of society as women have been in the past centuries. In his biography, Burt Lancaster: An American Life, the actor revealed to his director that he had so much surgery done on his face and body that “the most real thing on my face are my eyes.” John Wayne, Dean Martin and Gary Cooper were also known to have gone under the knife for various improvements. By the 1950’s, the bare-chested male ‘beefcake’ icon had been established. Mainstream film subject matter was changing too, it became more explicit and more violent. The male body was being re-established as the heroic, better-than-life Roman god again.

Superman, Batman, Ironman and the like, were also bursting onto the scene. Big, muscled and beautiful, these mythical males dominated and controlled the common man, making him appear small and incapable of looking after his world. The message was familiar: physical perfection, the appearance of power and beauty are essentials to be successful and a leader. Batman and Ironman, like most of their fellow heroes, were masked and anonymous and while never naked, the male characters were shown with every oversized muscle and bulge lovingly drawn for the reader’s objective gratification. These 1950’s superhero characters have since become household images, for young and old alike, reinforcing for us what ‘real’ heroes should look like.

With the end of the 1970s came The Chippendales and other male strip shows which had no cultural message to offer, no historic memories of past battles to remind us of – just pure entertainment. In the ’80s, as many as 900 women a night would press into Chippendales’ New York City club and chant: “We want meat! We want meat!” Today, some 250,000 people see the show annually.

“Chippendales levelled the playing field of sexuality,” says K. Scot Macdonald, co-author of Deadly Dance: The Chippendales Murders, which chronicles the dark side of the global phenomenon and business that launched in a Los Angeles dive bar in 1979.

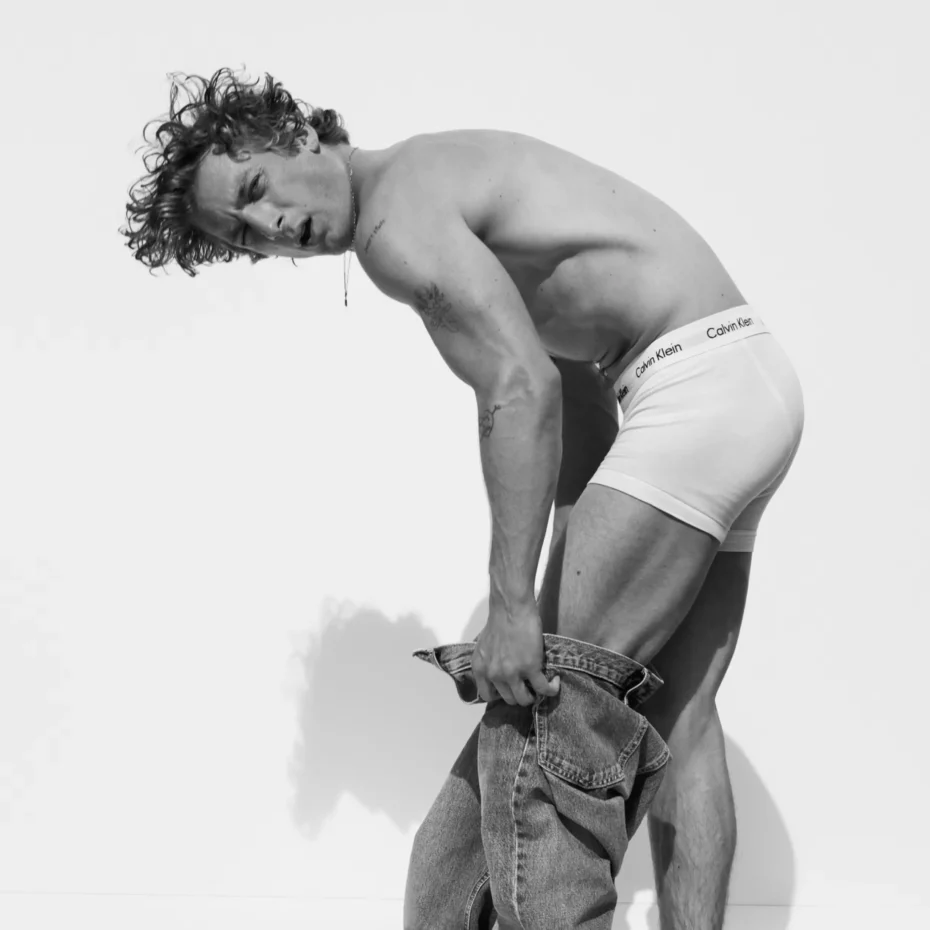

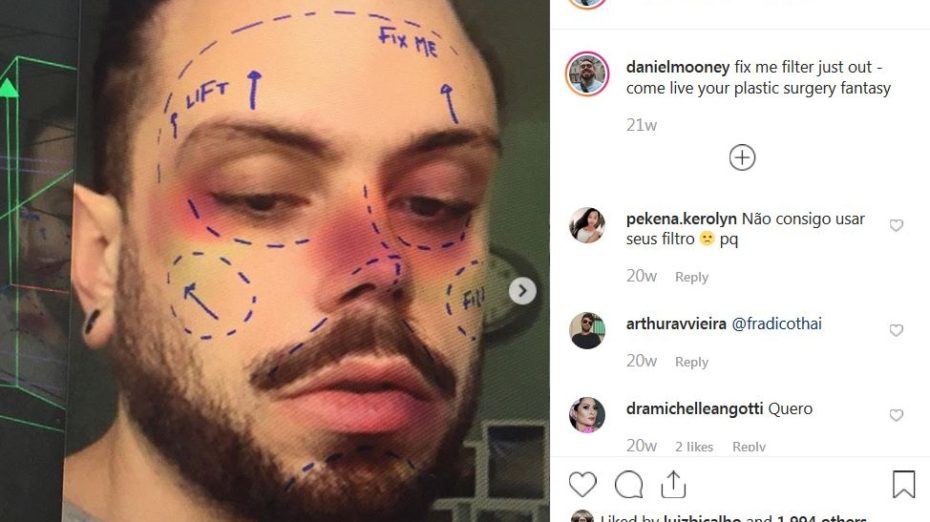

In the age of social media, both male, female and non-binary bodies are increasingly portrayed as objects that can be worked on to become more sexually attractive to others. The fashion and beauty industries, which have historically thrived on the practice of objectifying women, are becoming more gender inclusive, shifting their targets to men, transgender and genderqueer people.

So when it’s no longer just a women’s problem; when we come to realise that we’ve put the entire human race at risk of sexual objectification and all the mental health hazards that come with it, might we finally decide to stop doing it? Therein lies the eternal dichotomy: our lizard brains want to objectify ourselves and each other, while our 21st century brains know it’s a flawed and largely obsolete instinct. If history tells us anything, it’s going to be a hard habit to kick.