With the lights of Broadway and the West End lit once again, live theatre fans are dazzled anew by crashing chandeliers, green-skinned witches and rapping revolutionaries. But for all their glitter and grandeur, no modern musical can approach the absolute spectacle of the royal costume parties that played out on stage during the English Renaissance. Public theatre of the time – the kind William Shakespeare was producing – generally employed the simplest of set dressings, often just a few pieces of basic furniture or even a bare stage, but the 16th century saw the rise of the masque (not to be confused with mask), a form of amateur dramatic entertainment, popular among the nobility to entertain themselves until it became a legitimate art form. Henry VIII, Charles I of England and Queen Anne of Denmark and their relatives all performed in the masques at their courts, wearing disguises, play acting and dancing, as did the French Louis XIV, who danced in ballets across the pond over at Versailles. Under King James I and Queen Anne, these raucous amusements developed into a more formal but no less rowdy combination of theatre, ballet, ball and red carpet, staged to celebrate special occasions and holidays. The masque was the ultimate place to see and be seen; celebrity spotting was de rigueur; and the action off stage was often just as juicy as what was happening on stage. With that kind of competition for the audience’s attention, it’s no wonder the pageantry of the stage required sophisticated levels of innovation and showmanship…

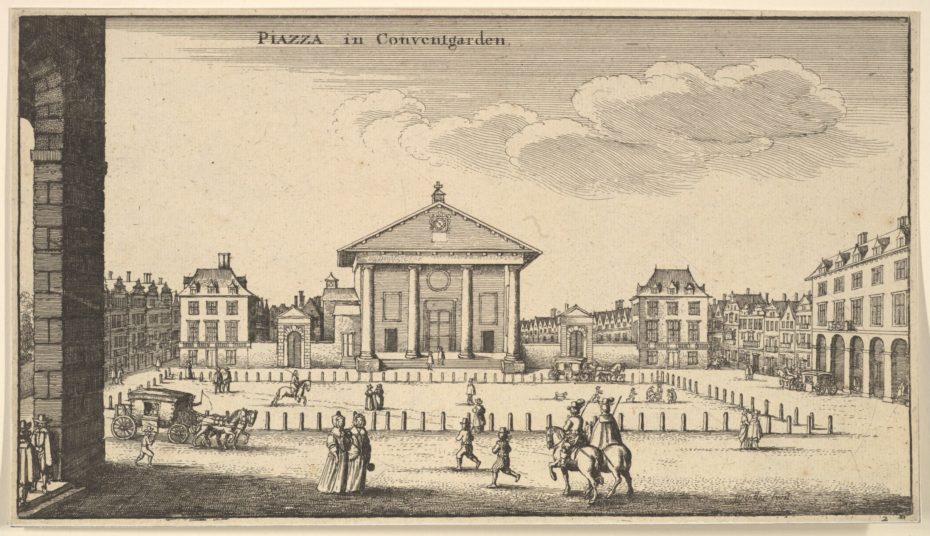

At the center of that spectacle was celebrated architect Inigo Jones, master of decorations and machinery. At first glance, Jones’s monumental accomplishments hardly seem relevant to courtly theatrical pursuits. As England’s first great architect, credited with introducing architecture from the Italian Renaissance and Classical Rome to the British landscape, he designed the first classical building in Britain, as well as Covent Garden, the first modern public square in London. He renovated and repaired Old St. Paul’s Cathedral; and even undertook a survey of Stonehenge by royal appointment. His fingerprints quite literally mark many of London’s most famous landmarks. But court masques were no humble black-box plays, and Jones’s architectural prowess may just give you a hint at the kind of opulence these performances displayed.

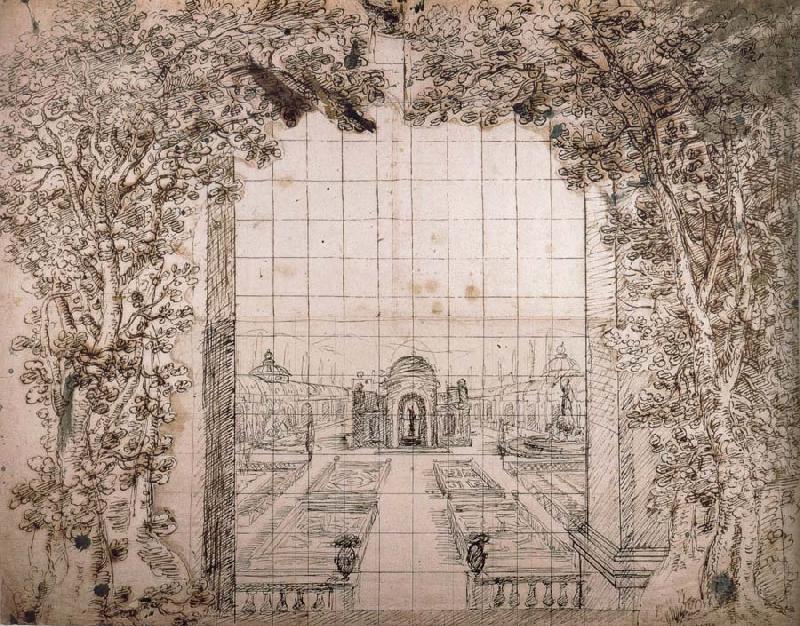

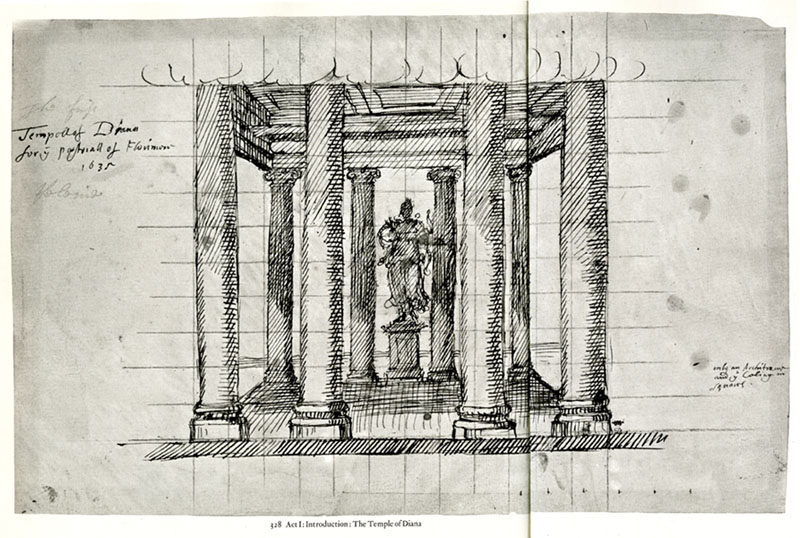

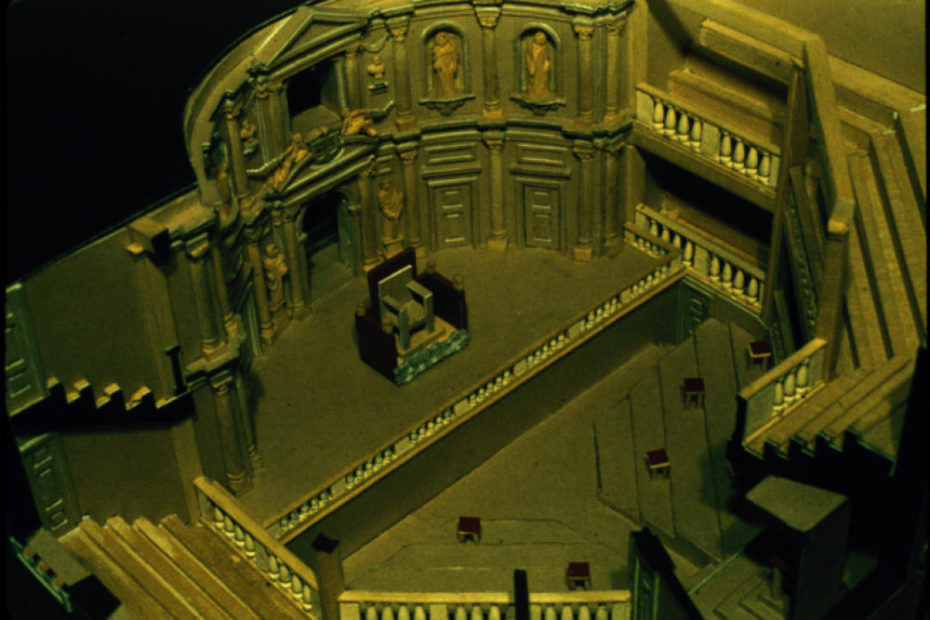

Inspired by his studies in Italy and under the patronage of Queen Anne, Jones introduced the proscenium arch to English theatre. A decorative frame that surrounds a stage space, this type of construction is designed to be viewed only from the front and allowed for the development of elaborate set pieces that played with forced perspective to give audiences a sense of being immersed in a real environment. Jones designed moveable scenery using shutters that slid on grooves in the floor or flew above the stage on ropes and pulleys. Sets often climbed to multiple stories or included large rotating globes. The Masque of Blacknesse included an artificial sea with waves that moved, as well as mermaids riding across the stage in giant shells, gods riding seahorses and six huge sea monsters carrying torchbearers. With audiences that talked through the performance and actors so drunk they could barely perform, the visual spectacle was essential to the success of the show.

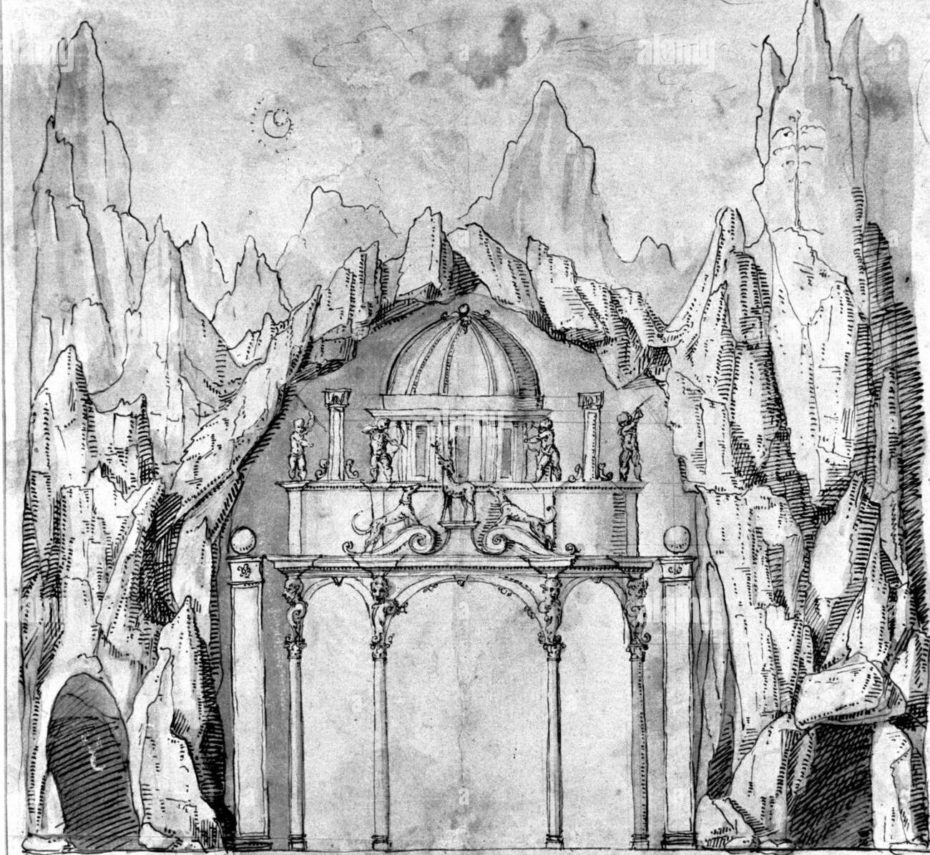

For Oberon, The Faery Prince, Jones’s set began as a pile of rocks that transformed into a glorious palace. And the Masque of Queens opened in a fiery hell replete with real flame and smoke, which vanished to reveal the House of Fame, filled with coloured lights reminiscent of rubies, sapphires and emeralds. Jones experimented with special lighting effects using oiled paper, colored glass and various screens to control the hue and intensity of lights on stage. The production of The Triumph of Peace, for instance, called for seventy dozen torches and sixty flambeaux. The light alone would have amazed audiences accustomed to comparatively dark manor houses and palaces. As Surveyor of the King’s Works, Jones even built a venue for the express purpose of staging masques, the Banqueting Hall at Whitehall Palace.

Jones’s costume designs were equally sumptuous and boundary pushing. All masques were political, a way to extoll the virtues of Stuart reign through a thin veil of mythological or classical theming. A stage full of gods, goddesses, nymphs and satyrs proved to be fertile ground for revealing costumes rendered in rich fabrics. A masque typically opened with an anti-masque performed by professional actors who donned grotesque costumes and makeup and danced wildly, symbolizing the chaos and misrule of a pre-Stuart kingdom. The main masque, which was meant to display the peace and harmony of divine rule, often included dances by members of the royal family and their courtiers. While women were barred from the public stage they did take on silent, dancing roles in the masque, and bare-breasted costumes were a common sight. Much like in paintings, allegory provided a (mostly) acceptable excuse for nudity that would otherwise be deemed indecent.

But such staging was not without controversy. Queen Anne faced criticism for her commission of and performance in the Masque of Blackness, both because her prominent acting role was seen as improper but also due to the masque’s use of blackface. The audience’s concern wasn’t about the harmful implications of racial impersonation to minority groups (a lesson some still have not learned 400 years later), but rather on the fact that paint was being used as a disguise instead of masks.

Jones continued work for the crown after Charles I succeeded his father, with the twice-yearly masques growing ever more elaborate. But the spectacle was not to last. The outbreak of the English Civil War effectively ended Jones’s career, when Parliament ordered the closure of all London theatres and banned public stage-plays. Charles I was executed at Whitehall Palace; he walked through the Banqueting Hall, the setting for so many memorable evenings of entertainment, on his way to the executioner’s block. Jones died in relative poverty a few years later in 1652.

Jones’s architectural and theatrical legacy lives on in an unlikely place: St. Paul’s Church, Covent Garden, affectionately known as the Actors’ Church. Jones was commissioned in 1631 to design the church and the rest of Covent Garden Square. In 1662 the Theater Royal, Drury Lane was established, followed by the Covent Garden Theater (now the Royal Opera House) in 1723. This was the beginning of London’s West End theatre district (think British Broadway) and St. Paul’s Church has been affiliated with the theatre ever since. Memorials inside are dedicated to actors and actresses from Charlie Chaplain to Vivien Leigh, and the church’s Portico was the site of the very first Punch and Judy show in the 1660s. Today, St. Paul’s supports its own in-house professional theatre company, Iris Theatre.