Every year, nearly a million people flock to Romania’s famous Bran Castle, a medieval fortress in Transylvania often referred to as the home of Dracula. Us mere mortals have a morbid fascination with the seductively taboo tales of vampires from deepest Transylvania and the immortal be-fanged and be-cloaked Count Dracula – but what of the Countess Dracula? As it turns out, there’s far more real-life demonic horror (and a real-life castle) attached to a historical female figure than there is to suggest a blood-thirsty male figure might have inspired Bram Stoker’s iconic lead character. Remembered as the “Blood Countess”, Elizabeth Báthory’s family ruled Transylvania, where she lived and died in a remote Hungarian mountaintop castle almost four centuries ago. Accused of trying to retain her youth by bathing in the blood of young servant girls, she was convicted of killing 80 people; though the death count was rumoured to be in excess of 650. Today, she still holds the Guinness World Records as being the most prolific female serial killer.

Under two hours’ drive east of Vienna, the ruins of her castle of Čachtice still hug the rugged Slovenian crag which, back in the 16th century was part of the lost kingdom of Royal Hungary. Caught between the Christian Holy Roman Empire in the west and the Islamic Ottoman Empire in the east, it was politically unstable for centuries and in 1526, partitioned between the Catholic Austrians, the Ottomans and the Principality of Transylvania in the south. Rivalries in culture, language and religion would plague Elizabeth Báthory’s homeland in a 3-way brutal religious war fought between the great empires of the day. Exceptionally privileged, with an elitist education, she was of Polish and Transylvanian aristocracy, but was also said to suffer from physical fits that may have been caused by epilepsy or other disorders as a result of family inbreeding. Medical treatment in those days entailed a concoction of herbal remedies intended to release demons and evil spirits trapped inside the body. According to some sources, remedies of the time involved blood rituals, possibly the drinking of the blood of non-sufferers.

Elizabeth was married off at the age of 15. Her social standing was superior to that of her husband Count Ferenc II Nádasdy, who adopted her surname along with her wealth. Elizabeth’s dowry was the castle of Čachtice in the Little Carpathian Mountains in present-day Slovakia, a fortress that would become her home and eventual prison.

With her husband away at war leading the Hungarian armies against the Ottomans, a very capable Elizabeth managed both her business affairs and the defence of her vast estates that were spread across Royal Hungary, many of which guarded the military routes to Vienna in the north. But at the dawn of the 17th century, around the time of her husband’s death, strange rumours started to emerge from Čachtice castle about various ghastly and gory goings-on, including the abduction and torturing of young girls and women.

Initially, the Hungarian aristocracy didn’t react, presumably because of Elizabeth’s status, but by 1610 her overlord was pressured to send an investigator. It’s also been suggested that no one really batted an eyelid at the mutilated bodies of peasant girls, but when Báthory allegedly started going after daughters of noblemen, something had to be done.

György Thurzó, an ambitious royal courtier, to whom the late Count Báthory had entrusted his widow’s estate, was quick to take matters into his own hands and started collecting local witness statements. The documents recorded accounts from locals that described horrific beatings, torture and murder of both servant girls and the daughters of the lesser gentry who were sent into Elizabeth’s care by their parents to learn the ways of the royal court. The sensational accusations included cannibalism, together with the burning of victims with hot tongs and then placing them in freezing cold water. Perhaps even more gruesome was the claim that Báthory had covered her victims in honey and live ants. There were over 300 witness statements, some of which were also provided by royal court insiders who even claimed to have witnessed the torture themselves.

Elizabeth Báthory was arrested in the winter of 1610. Historical accounts say she was caught in the act of torture and rounded up by villagers, while others suggest she was merely having dinner when authorities arrived at her home. One or more mutilated dead bodies and a girl, barely alive, were found in the castle according to records.

Two different trials were held and drew on many of the hundreds of witness testimonies, most of which were not eye witness accounts. Grotesque story details, from the macabre to erotic painted the picture of a blood-thirsty countess; an evil demoness who bathed in the blood of virgins in order to regain her youth. It’s been suggested that she may have had a severe iron deficiency and that drinking the blood of the girls was thought to bring the colour back to her face. Four servants who were arrested with Elizabeth and accused of being her accomplices, confessed under torture and were executed shortly after.

The prosecutors sought to convey that Elizabeth Báthory was the leader of a dark ring of female ritualistic torturers and murderers. The trial claimed there were up to 650 victims, which by modern definition, would establish Elizabeth Báthory as the ‘greatest serial killer in history’.

Some historians believe she was set up, arguing that the proceedings against Báthory were largely politically motivated, due to her extensive wealth and ownership of large area in Slovakia and Hungary, escalating after the death of her husband. Perhaps tellingly, Elizabeth Báthory was not executed, but imprisoned in her own castle to protect her family from scandal, and maintain political stability in Royal Hungary. The main orchestrators of her trials were promoted to positions of higher power following her detainment. György Thurzo, who stood to gain control of the vast Bárthory estate, gave his own account of finding Báthory covered in blood upon his arrival at her castle. Incidentally, her wealth had substantially increased after the death of her husband and the Austrian archduke owed Báthory a large debt, which was conveniently cancelled upon her arrest. She was walled up in her bed chambers, with a small opening to allow food, drink and proper ventilation to be passed through.

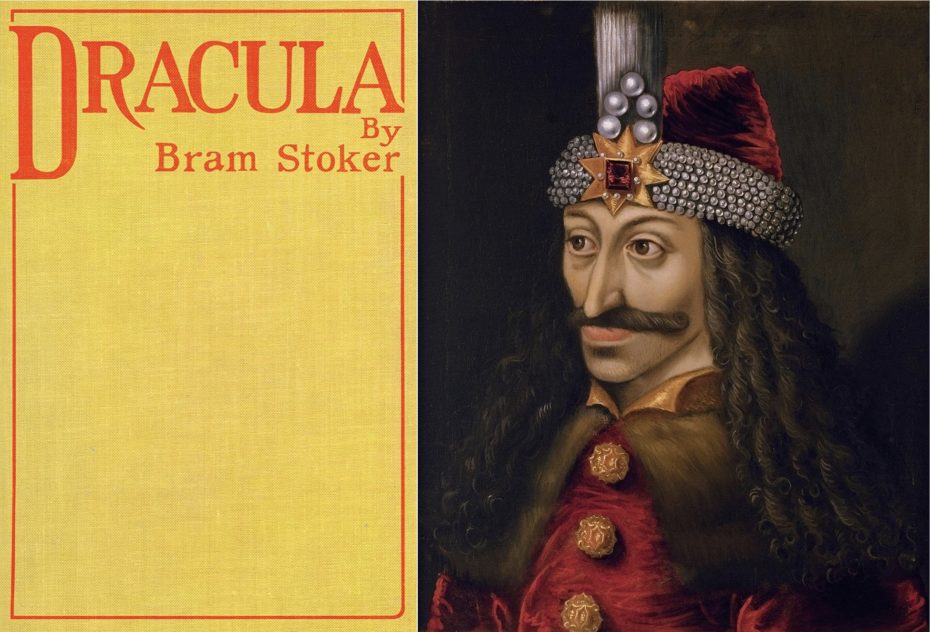

The countess died under house arrest at her castle of Čachtice in 1614 at the age of 54. History rolled on, the wars in Hungary continued unabated for centuries as did the tales of the countess. Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula was published at the end of the 19th century, believed to be based on the grizzly wartime exploits of “Vlad the Impaler”, a famous medieval Romanian ruler and warrior, née Vlad Dracula, the second son of Vlad Dracul. But aside from his name establishing the connection with vampirism, with aid of hindsight, much of the ritualistic content of the novel seems instead to flow from the records and tales of Elizabeth Báthory’s trial.

The world was immediately captivated by Stoker’s dark fantasy that mixed historical folklore with gruesome fiction, set amidst the mysterious beauty of Transylvania. The story would erupt through 20th century film renditions. Perhaps the most enduring are the Dracula films from the 1960’s where actor Christopher Lee made the role his own as the monstrous yet polished undead count. The movie formulas heavily leaned into the narrative of secret blood rituals to sustain the count’s devilish immortality – echoing the accusations that Elizabeth Báthory’s faced 350 years earlier.

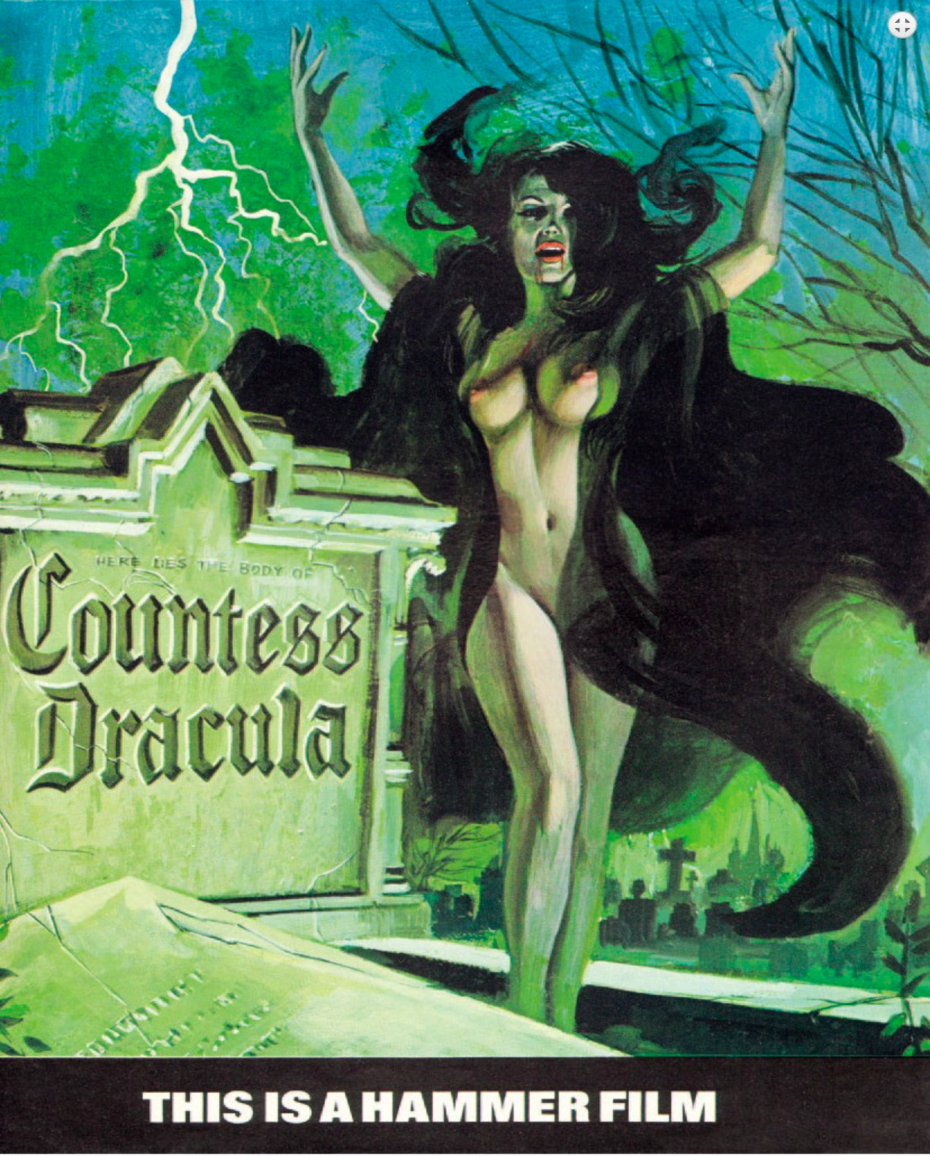

In 1971, two Hungarian emigrés produced a new movie ‘Countess Dracula’, which told the story of a beautiful but bloodthirsty, blood-bathing, virgin-slaying vampire fighting for youthful immortality in her Transylvanian lair. The character was an overnight sensation, briefly eclipsing her male namesake.

In the late 2000s, both Anna Friel (Bathory, 2008) and Julie Delpy (The Countess, 2009) played Elizabeth Báthory in two different biopic of her life, free from the obvious cliched vampire myths, but still portraying her as a twisted murderess on a blood-guzzling campaign of sexual conquests to restore her youth.

Hundreds of years later, Elizabeth Báthory remains branded as one of history’s most merciless and deplorable women. Vlad the Impaler, on the other hand, is considered more like a freedom-fighting national hero in Romania (think Braveheart), despite massacring tens of thousands of Turks and Bulgarians. Go figure. The residence and prison of the “bloody countess Elizabeth Bátory” was neglected and burned down in 1799. What’s left of it can be found at the end of a marked trail from the town of Čachtice, offering a beautiful panorama of the Carpathian Mountains. And hidden amongst the blood-soaked ruins, who knows? You may just find Elizabeth’s fountain of youth…