Silver screen icon Anna May Wong is likely the only Asian-American actress from the Golden Age of Hollywood that any of us have heard of. From the dearth of information on any other Asian-American actress, it may seem as if Wong was all alone. But contrary to what mainstream narrative would have you believe, there were always Asian-Americans in cinema. Many of them were either cast as vamps or villains, which put them in poor favour with Japanese and Chinese communities of their time, or more often, they were relegated to B-movies or bit roles. Miscegenation laws also kept Asian American actors from having a romantic leading role with a white actor, which meant losing roles to white actors in yellowface. For many of these aspiring performers, all that is left of their attempts to crack the colour barrier in Hollywood are their fleeting film appearances, a few intriguing articles in movie magazines, and the glamorous photographs they left behind. Today, we’re shining the spotlight on some Asian-American names and faces forgotten in film history…

Toshia Mori

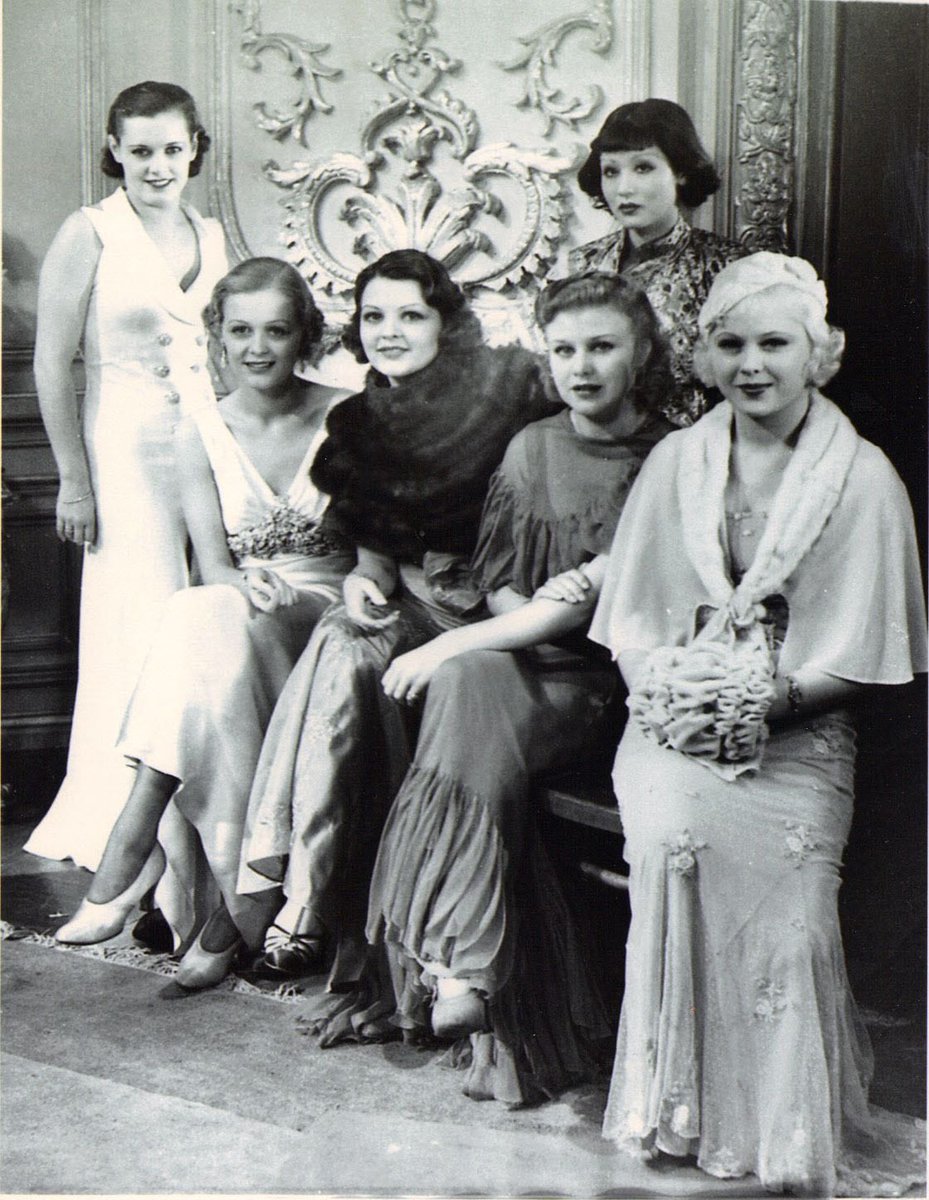

Each year from 1922 to 1934, the Western Association of Motion Picture Advertisers (WAMPAS) selected thirteen young actresses to promote as a WAMPAS Baby Star. It was considered a golden ticket to stardom, bringing attention to actresses like Joan Crawford and Clara Bow when they were still unknown. In all the twelve years that this promotional campaign existed, the only non-Caucasian WAMPAS Baby Star was Toshia Mori (pictured above, far left).

Born in Kyoto in 1912, Mori emigrated to Los Angeles when she was ten years old. As a teenager, she began appearing in bit roles, often uncredited, but occasionally billed under her birth name Toshiye Ichioka. When Lillian Miles dropped out of the WAMPAS Baby Star line-up in 1932, Columbia Pictures chose Toshia Mori as a replacement. Other WAMPAS Baby Stars of that year included Ginger Rogers before her star-making partnership with Fred Astaire, and Gloria Stuart, whose career was revived in 1997 after she played the older Rose in The Titanic.

Mori was whisked into a flurry of WAMPAS publicity including a cringeworthy promotional short, in which she is introduced as, “Toshia Mori, a bit of Dresden China.” Mori responds, “No, I’m not Chinese. I’m Japanese.” Her polite smile freezes as the announcer replies in a mock Asian accent, “Oh, ‘scuse please!”.

Watch the exchange below:

Mori appeared in seven films in 1932. Her biggest role was the duplicitous other woman in Frank Capra’s The Bitter Tea of General Yen with Barbara Stanwyck. After that, Columbia seems to have lost interest in exploiting her potential. She was loaned to MGM for a fleeting appearance as a dancer in Greta Garbo’s The Painted Veil and then relegated to B-movies. She at least got a chance to play a spirited women with speaking lines in her last two films, Charlie Chan at the Circus and Charlie Chan on Broadway. Mori was just 26 when she stopped making films.

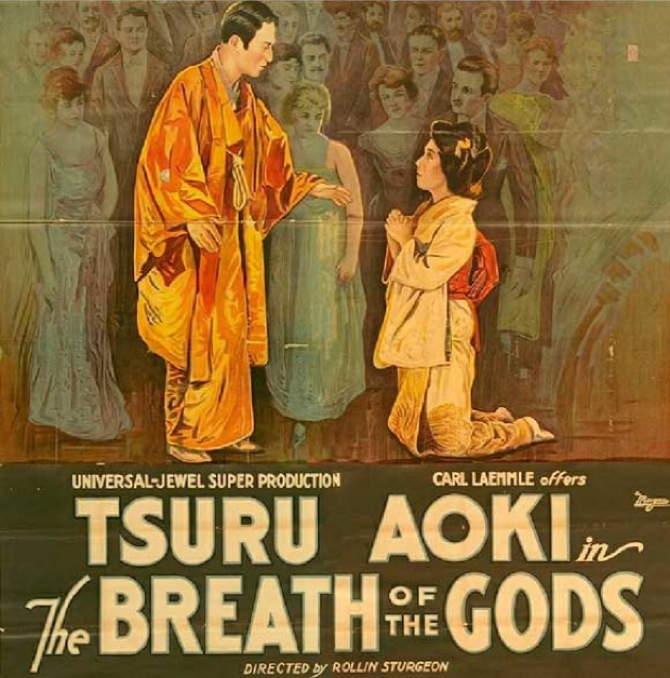

Tsuru Aoki

Tsuru Aoki came to America in 1899 as a child actress in the first kabuki company to travel to the West. Her aunt was the legendary geisha Sada Yacco and while travelling with the family’s company in San Francisco, it was arranged for Tsuru to be adopted by Japanese artist Toshio Aoki rather than drag her into the unknowns of Chicago. In 1913, she was performing at a Japanese theater in Little Tokyo when she caught the eye of film pioneer Thomas Ince. She made her first film that year, The Oath of Tsuru-San, a drama of interracial love and betrayal. She would later introduce Ince to Sessue Hayakawa, another Japanese actor who had drifted into the theatre scene after a string of menial jobs. Hayakawa was hired and made his film debut in Aoki’s second film, O-Mimi San.

Aoki married Hayakawa in 1914. A year later, her husband found fame playing a sexual predator in Cecil B. de Mille’s The Cheat and became the first actor of Asian descent to achieve stardom as a leading man in the United States and Europe. “Broodingly handsome”, along with Rudolph Valentino, he became one of the first male sex symbols of Hollywood.

The couple became Hollywood royalty, throwing lavish parties with celebrities passing out on bootleg liquor in their enormous mansion, Castle Glengarry, a replica of the castle in Scotland. They were so successful that in 1918, they formed a production company to gain greater creative control over their films. But the party was over by the 1920s. A combination of a bad business deal and growing anti-Asian sentiment led Aoki and Hayakawa to leave America in 1922. After 1924, she disappeared from filmmaking to raise their three children. In her one decade of filmmaking, Aoki had starred in 40 silent films.

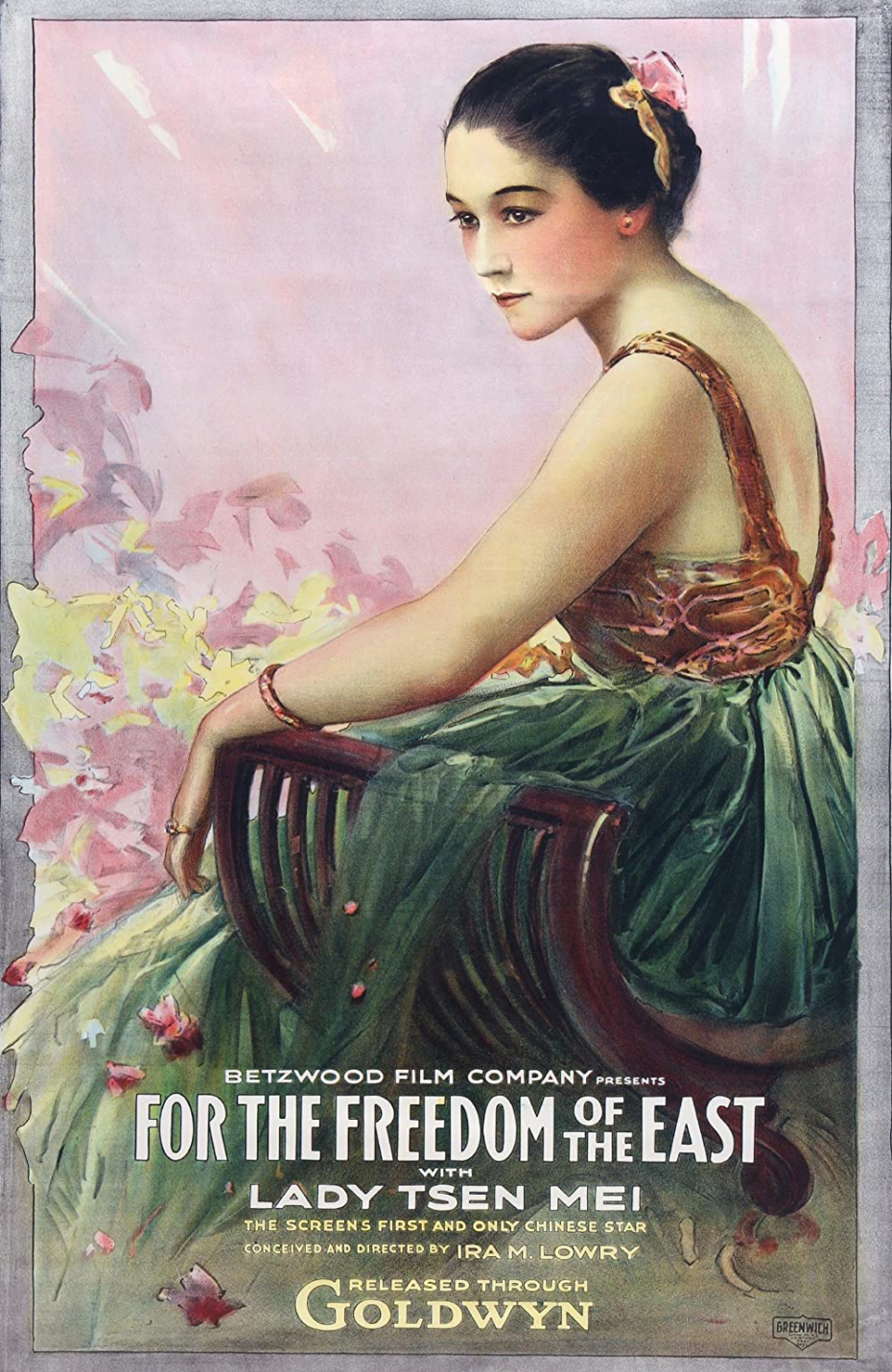

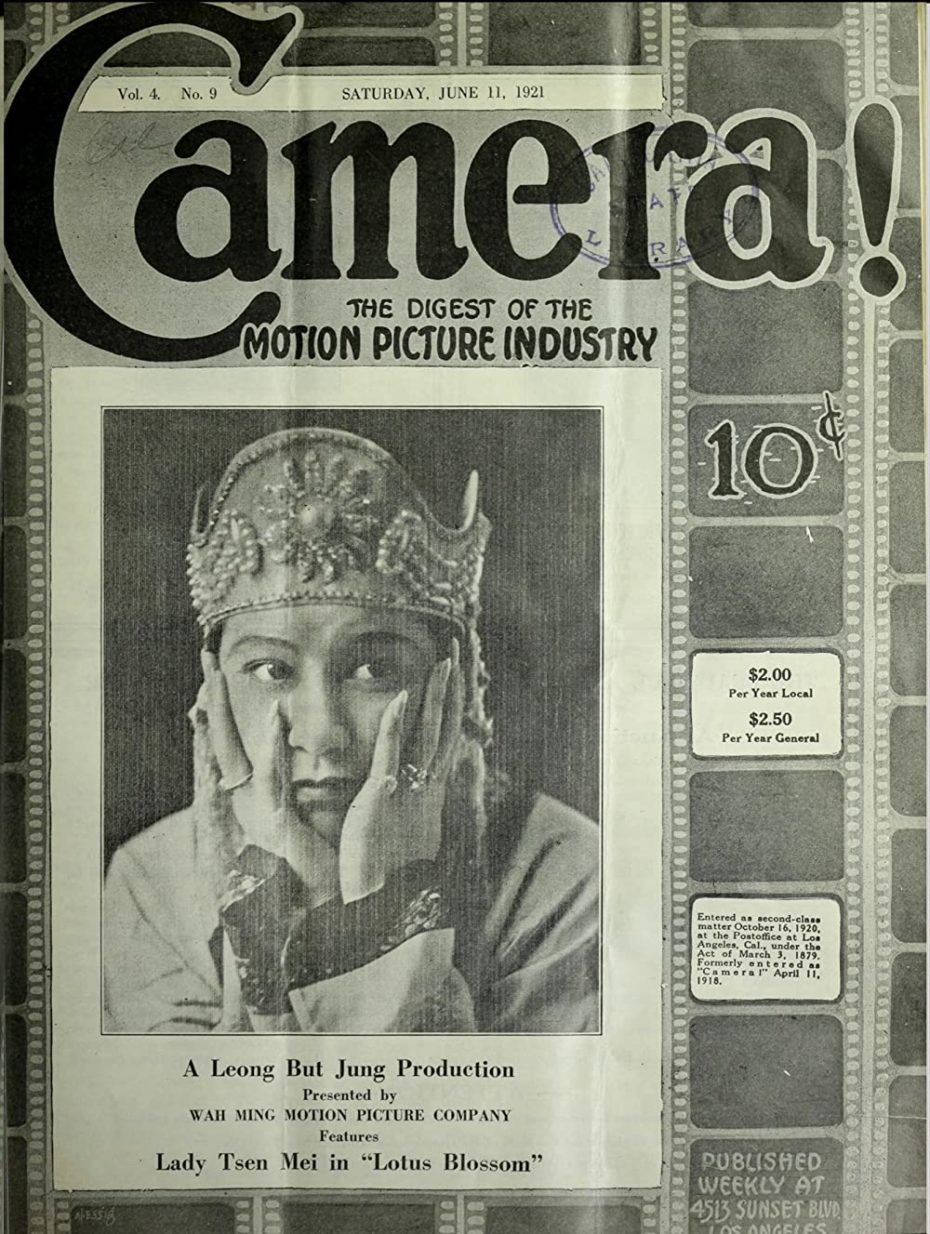

Lady Tsen Mei

Lady Tsen Mei’s exotic name came with a back story that she was born in Canton to a noble family and graduated Columbia Law School. She was actually born Josephine Moy in Pennsylvania in 1888. Her father was Chinese and her mother was part Black, making her the first Black Asian movie star. At age of two, her mother died of consumption, and she was adopted by Jin Fuey Moy, a physician who also worked for the U.S. Immigration Bureau before he was discharged for smuggling Chinese immigrants into the United States.

In the 1910s, Lady Tsen Mei became known in vaudeville as the “Chinese Nightingale.” Her act consisted of imitating a variety of birds and demonstrating a vocal range from male baritone to lyric soprano, and her popularity led to a starring role in the lost World War I love story For the Freedom of the East, filmed in 1918 at Betzwood Pictures in Pennsylvania. She followed her luck to Los Angeles, where she was next seen in Lotus Blossom, directed by Chinese-American director James Leong. The film premiered in 1921 at the Alhambra Theatre with two Asian hostesses at the door, one of whom was Anna May Wong, a year before her breakout role in The Toll of the Sea.

Lady Tsen Mei’s only surviving film is a pre-Code murder drama, The Letter (1929) with the legendary Jeanne Eagels. Playing Eagels’ romantic rival Li Ti, she is strangely awkward in the beginning of the film, burdened with a terrible quasi-Asiatic accent. But in the pivotal scene when she blackmails Eagels’ character, she lets it rip. The role was expanded from the Broadway play for Lady Tsen Mei and she makes a gleefully vicious adversary, as she forces Eagels to grovel in front of her. Eagels overdosed soon after making the film and posthumously received an Academy Award. Lady Tsen Mei was the first actress of color given a full-page feature in Photoplay magazine.

Etta Lee

From 1921 to 1935, she appeared in 17 films as a maid, a manicurist, or slave girl. Her biggest maid role was in The Untameable, promoted as the most shocking film of 1923, where she plays the loving and possibly lesbian servant of a woman who develops a split personality after being hypnotized. The only film where Lee wasn’t cast in a subservient role was the 1929 historical short Manchu Love, an early colour experiment in which she played the Empress Tsu Hsi. Despite her bit roles, Lee was the subject of several articles in newspapers and movie magazines. In 1923, Motion Picture Classics lamented that her first name wasn’t exotic enough and chastised her for not speaking Chinese.

Born in Hawaii, Etta Lee’s father was Chinese and her mother was French. She had been working as a teacher when a chance encounter with the wife of a director led her to Hollywood.

On film, Lee manages to come off as smart and insightful despite the very cringeworthy treatment she is given. She later lamented in a 1924 Bismarck Tribune article, “By heritage, temperament, and the trend of self-culture, I am equipped and moved to depict odd, bizarre, exotic, extravagant gesture-thoughts… But in this field I have not yet had opportunity.” Lee married radio announcer Frank Brown in 1932 and left filmmaking soon afterwards to resume her teaching career.

Anna Chang

A vaudeville performer who started singing professionally as a teenager, in 1928, Anna toured the United States with the variety revue Hula Blues, “a new kind of Hawaiian beauty show which entrances its auditors with its soft, melting harmony, and twanging ukuleles.” She received star billing for Singapore Sue (1932), a short film mostly remembered for being Cary Grant’s debut role. The slim plot follows four sailors looking for fun at a dive bar in an exotic locale. The dialogue is awful and Grant was later embarrassed about his hammy acting. But when Chang casts off the bad script along with the Chinese robe, she shows why she was so popular in vaudeville. Cute as button, she warbles a sassy song while sashaying around in a spangly leotard and knocking off the sailors’ hats. The short also features Joe Wong, whose sweet tenor voice made him a staple on radio programs through the 1950s.

Chang’s only other film appearance was in The Hatchet Man, featuring an all-yellowface cast (similar to the practice of blackface used to represent African-American characters) led by Edward G. Robinson and Loretta Young. All the actual Asian people in this Chinese mafia story went uncredited. After this debacle, it seems that Chang had enough. She returned to San Francisco to sing at the Jade Palace, a stylish cocktail lounge in Chinatown.

Lotus Long

Lotus Long spent most of her career bopping around B-movie lots playing exotic island girls and characters in poverty row detective films. Part Japanese and part native Hawaiian, born in 1909 in New Jersey, she co-starred with Inuit actor Mala in Last of the Pagans, a 1935 thriller about South Pacific lovers separated by an exploitative European mining camp. She is seen in two Mr. Moto mysteries starring Peter Lorre in yellowface and two Mr. Wong detective films with Boris Karloff in yellowface.

Karloff played Mr. Wong five times before Monogram Studios gave Chinese-American actor Keye Luke his one and only chance to star as the detective in Phantom of Chinatown. For this film, Long plays the secretary of an archeology professor who is killed because of a mysterious scroll. It’s a rather bland B-movie but it does challenge the stereotype of Asian-Americans as perpetual outsiders. Both Luke and Long are clearly American with their snappy dialogue and snazzy 1940s suits.

Long’s last film appearance was in the 1946 thriller Tokyo Rose, where she played the title role. Presumably, her Chinese-sounding artist name saved her from being sent to a World War II Japanese internment camp after Pearl Harbour.

Maylia

When Gloria Chin left Detroit to visit her sister in Los Angeles in 1947, she probably did not expect her life to change drastically. But at a fairytale visit to a Paramount canteen, she not only scored a screen test, she also fell in love at first sight.

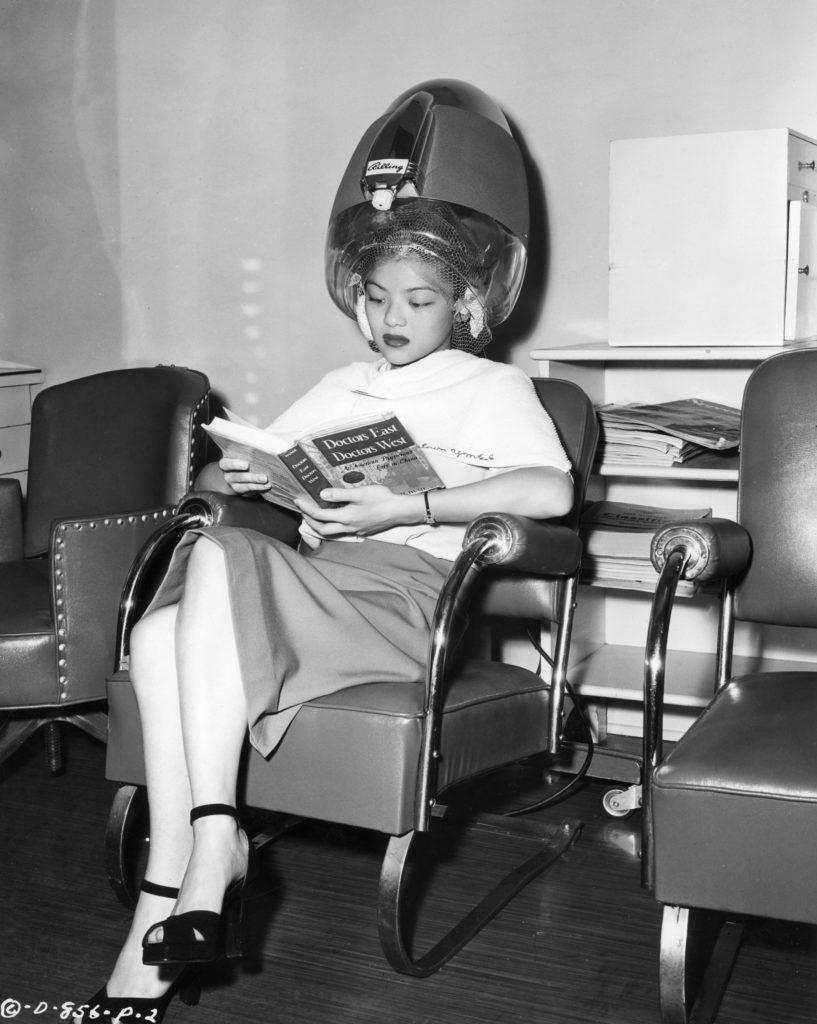

Spotted by a Hollywood insider at the canteen who was looking for an Asian-American actress for his dope smuggling thriller, To the Ends of the Earth, the encounter led to a screen test where she signed with Columbia Pictures and was given the exotic name Maylia.

At the canteen, she also met Benson Fong, who had a regular role in the Charlie Chan films. They were married three weeks later. At the suggestion of Gregory Peck, she and Fong later started a chain of Chinese restaurants.

Maylia spent 1947 making her two biggest films. In To the Ends of the Earth, she plays a teenage Chinese girl who (spoiler alert) turns out to be a secret narcotics kingpin. She nailed the tour-de-force role but it didn’t catapult her to fame. She played the former maid of woman suffering from amnesia in the film noir Singapore, a Casablanca copycat starring Ava Gardner and Fred MacMurray. After two more negligible film noirs, she left films to manage her restaurant empire and raise five children.

Things have changed since the Hollywood studio days but there’s still a long way to go. During the rise of racial consciousness in the 1960s, Asian-Americans followed in the footsteps of Black Americans to assert their own identities. Beulah Quo, who had appeared in a small role in Love is a Many Splendored Thing (1959), got together with seven other Asian-American actors who were tired of tiny roles and stereotypical characters. They founded East West Players in 1965, which jump started a growing number of Asian-Americans in theater and film. In 1982, Wayne Wang launched Asian-American independent films with Chan is Missing, which referenced all those Charlie Chan films that Asian-Americans had been relegated to in the Hollywood Golden years. But after decades of pounding on the Hollywood door, representation is still inadequate and negative stereotypes persist. In a recent interview with TIME magazine, actress Awkwafina noted, “you don’t understand how important representation is until you see it and realize you’ve been missing it your whole life.” There is hope, however, that things are changing with the success of Crazy Rich Asians, followed by The Farewell, Minari, and Shang-Chi. After a hundred years, we can finally name more than one Asian-American actress in Hollywood films.

About the Contributor