There’s a famous American song “Yankee Doodle” – you might’ve heard of it – the lyrics go like this: “Yankee Doodle went to town, A-riding on a pony, Stuck a feather in his cap, And called it macaroni.” The familiar patriotic tune was in fact created by the British to mock the Americans during the War of Independence – the joke being that the American colonists were considered so unsophisticated, that by merely sticking a feather in one’s hat to embellish their look, they thought they could consider themselves fashionable, or as the English would say, “macaroni”. It’s a word which you and I would ordinarily associate with the cheesy pasta bake best served to soothe a decidedly unglamorous hangover, but the term was once so embedded in British society, that the verbal seal of approval for all things in vogue, was to describe them as ‘very macaroni’. Think of it like an 18th century label for “hipster”, a buzzword of yore, used to describe a stylish fellow who paid attention to his appearance, and dressed in an embellished androgynous style. The macaroni look got its name at the time from the rising excitement around the Italian pasta, which was a then-novel and exotic delicacy being brought back to England by aristocratic young men returning from their ‘Grand Tours’ of Europe. The underlying inference was that these dapper gentlemen who had developed a taste for the tube-shaped pasta on their international voyages, were said to belong to the Macaroni Club; a subculture of worldliness, superior style, sophistication and enlightenment; a precursor to the 19th century dandy. But the world wasn’t ready for the Macaroni, and the short-lived fashion subculture would swiftly fall victim to stereotype and disappear into the shadows of polite society. Because if a man showed just a little too much enthusiasm for fashion or interest in effeminate bourgeois excess, he was of course ripe for ridicule…

For the upper class male traveller on an 18th century ‘gap year’, there was a whole new world gagging to be experienced, well beyond that of art and architecture. While a small contingent of the well-heeled were focused on the crumbling ruins of antiquity, many preferred to indulge in the sizzling hot Tuscan summer days and secluded Roman bathing pools; sticky intimate Athens evenings with flowing wine and the ripe juicy fruits of the Mediterranean – certainly a whole lot more rewarding than what was on offer back in wet ol’ Blighty.

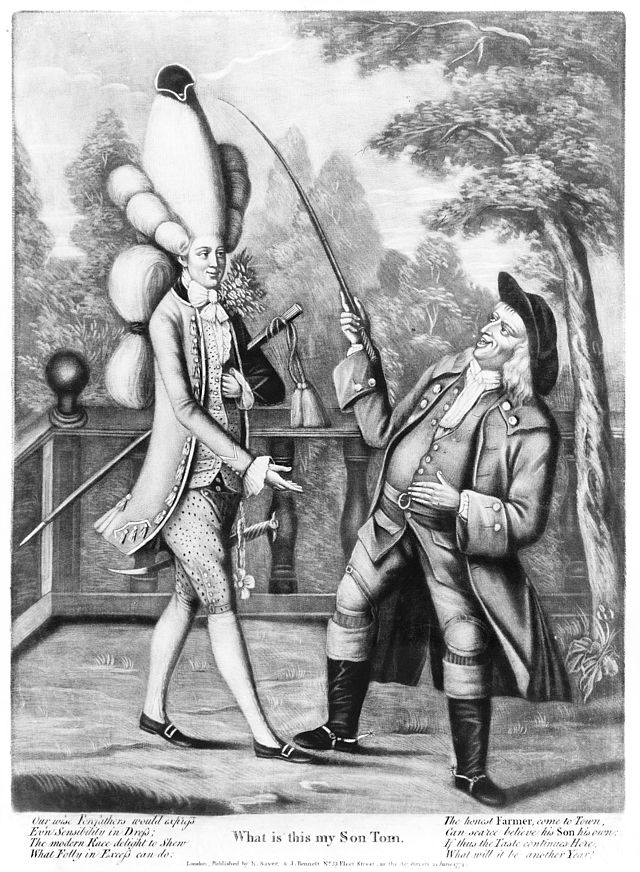

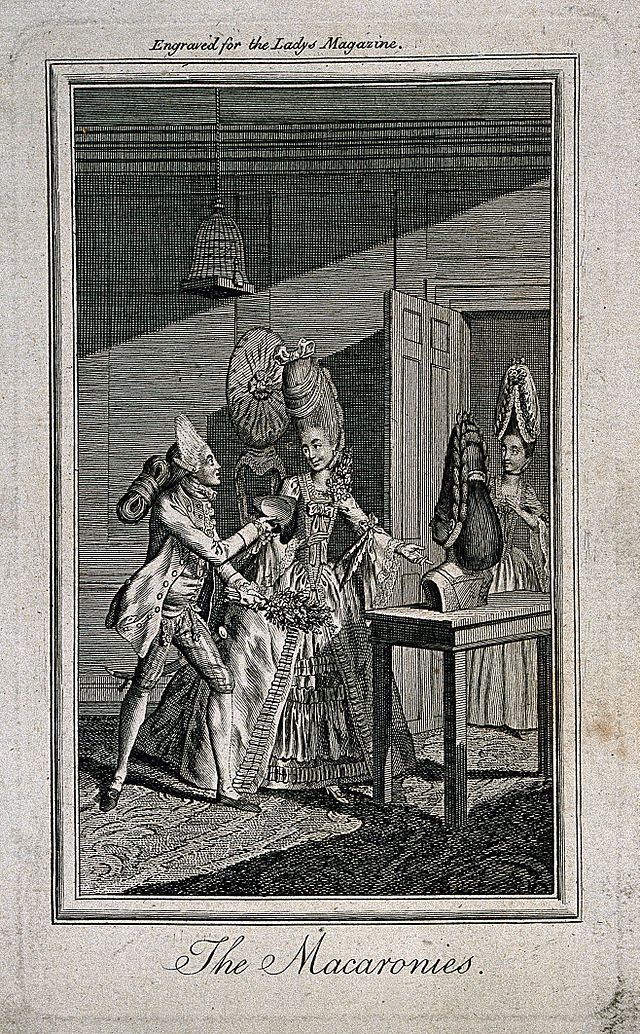

Europe offered a bohemian frenzy of feasting and festivals, of dressing up and dressing down, a riot of debauchery. The pursuit of pleasures of the flesh were the order of the day and bordellos were covetable beacons. To be a convincing macaroni, it wasn’t enough to just enjoy oneself abroad however, you had to bring proof back home with you; portraits in front of the great monuments, etchings of the ancient ruins and the latest continental fashion – clothes, shoes and fabrics from Paris and Milan. Britain was at war with France at the time and the import of French silk had been banned, but the fashionable elite would smuggle in their own superior quality silks in the most avant-garde of designs for their return into British high society. Lace ruffles exploded from contrasting cuffs and collars of French silk coats were swept back to expose the most delicately embroidered waistcoats, partly unbuttoned of course, to display a riot of chest brooches. Tight clinging velvet breeches, barely to the knee, met fitted embroidered silk stockings and the most exquisitely decorated Spanish leather heeled shoes.

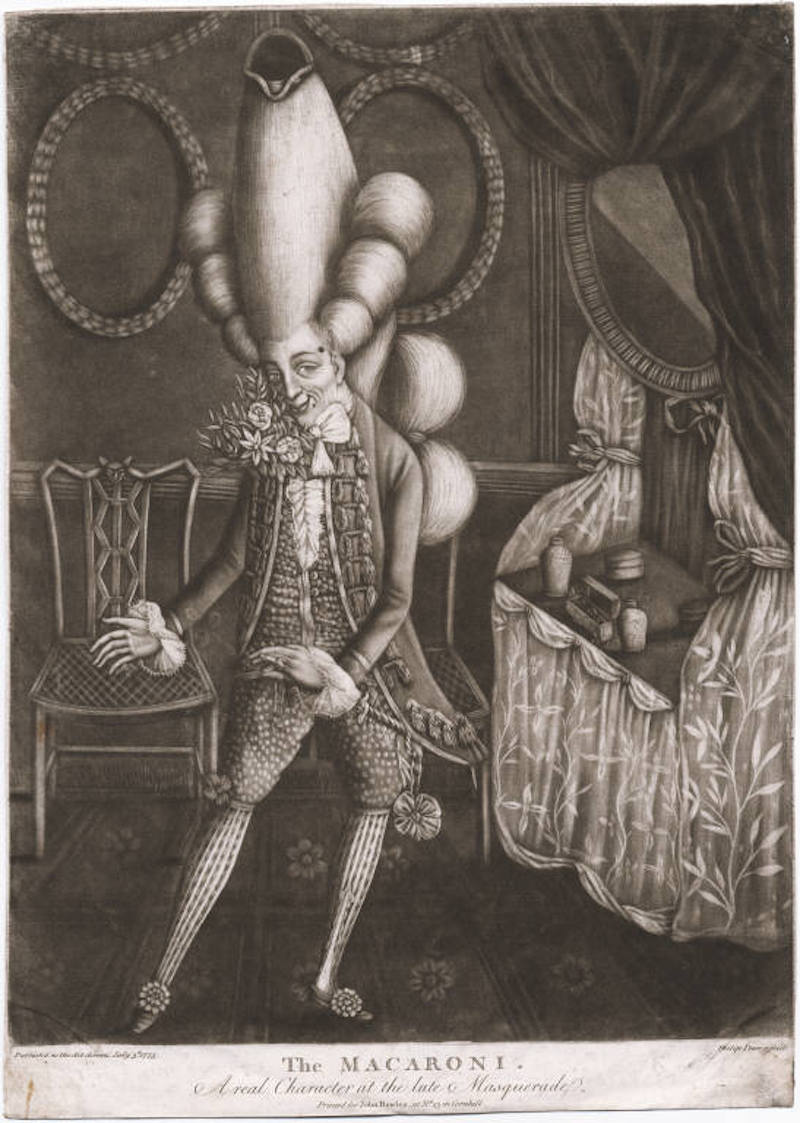

A macaroni might also follow a vigorous beauty regime, sporting rouged lips and cheeks, pox patches, powdered wigs and bejewelled fingers with painted and manicured nails – as was the fashion in France for both male and female courtiers. For accessories, he might even carry a parasol or wield the most elaborate of canes, and step out in extravagantly trimmed and feathered hats – this is thought to be why the Macaroni Penguin is so named, despite living an entire hemisphere away from Italy.

Shrouded in a rainbow of ribbons and bows, a macaroni’s pièce de résistance was the monumental, oversized, over-sculpted and over-powdered wig. Their bejewelled wigs would stand a metre tall, bulging and billowing, resembling giants ice creams sprinkled with rainbow-coloured candy.

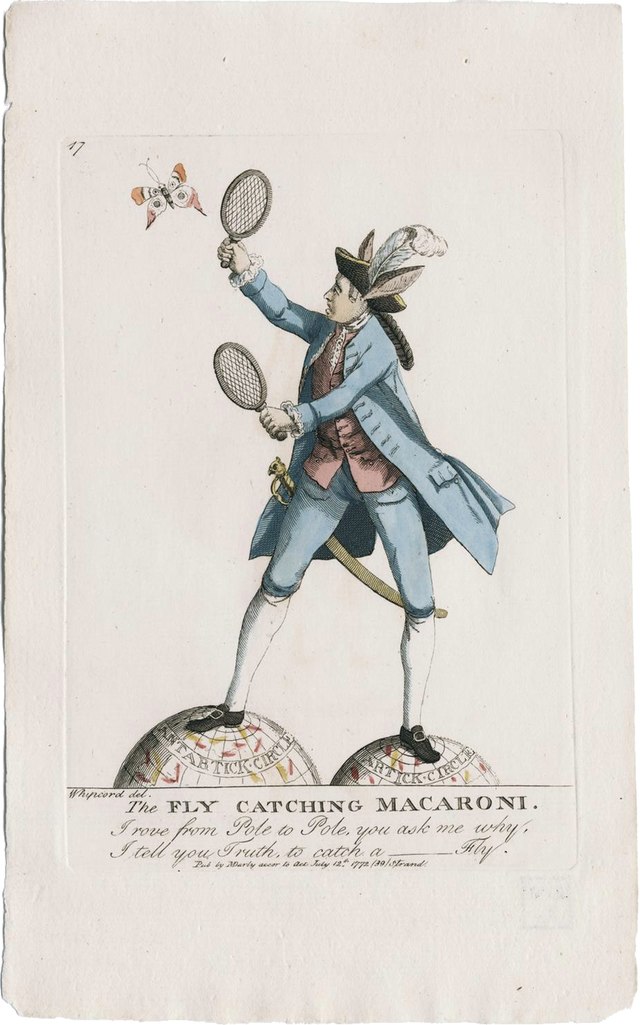

This lovingly decorated, daringly outrageous but exquisitely tailored creature became the public image of the macaroni. Entirely for display, part male, part female, this was the world of the decorated peacock, the 18th century drag artist meets rock star, strutting his stuff on the catwalk of life.

In his illustrated book, Pretty Gentlemen, fashion historian and professor Peter McNeil links macaroni fashion to modern-day drag queen glamour. “Some macaronis may have utilized aspects of high fashion in order to affect new class identities, but others may have asserted what we would now label a queer identity”.

Initially seen as alternative and odd, rather than aggressively anti-establishment, their distinctive fashion sense would be enthusiastically tolerated, entertained, even enjoyed by an amused public. These well-travelled, dapper, dainty and sensitive aristocrats sought to build a distinctive image of themselves and their circle through unorthodox behaviour, dress and attitude. Late 18th Century Britain was awash with societies and clubs, attended by aristocrats who loved gambling, foreign fashions and celebrated the height of macaroni fashion. Estates were won and lost at the card-tables and promiscuous behaviour was rampant behind the veils of Georgian etiquette.

At the same time, the early 1770s saw the rapid growth of the media and in particular, printed newspapers and pamphlets. The public’s appetite for the ridicule of the upper class turned out to be insatiable and for caricaturists, the macaroni was the perfect subject matter.

The first, non-food reference to macaroni in England was the character of the Marchese di Macoroni, a character in David Garrick’s effete society play of 1757, The Male Coquette – a coquette being a flirtatious woman. This character was modelled on the immaculately dressed aristocrat, sensitive and effeminate in demeanour, existing somewhere between the sexes and concerned with the ‘finer things in life’. Their dress was exotic, their behaviour silly and their eating habits fussy, picky and attention-seeking. Shunning traditional dishes like roast beef, they deliberately plumped for ‘exotic’ Italian pasta and their conversation was an extension of their eating habits, consisting of suggestive mutterings and effeminate blethers.

They were described at the time as “a kind of animal, neither male nor female, a thing of the neuter gender, lately started up among us. It is called a macaroni. It talks without meaning, it smiles without pleasantry, it eats without appetite, it rides without exercise, it wenches without passion.” In 1773 James Boswell was on tour in Scotland with the robust intellectual Dr. Samuel Johnson, well known as a practical man from London. Johnson was awkward in the saddle and Boswell teased him, “You are a delicate Londoner; you are a macaroni; you can’t ride”.

What began as a poke at aristocratic privilege soon turned more sinister, most notably with the scandal of Captain Jones in 1772. Jones, evidently a ‘sensitive’ military man and society macaroni, wrote books on the making of fireworks and on the pastime of ice-skating, where in the latter, he extolled the virtues of aesthetic poses, by males, while in motion. He had been found guilty of sodomy, a capital offence at the time and was forced to leave the country to avoid a death sentence. One of the socialite writers of the time, Hester Thrale, apparently had the uncanny ability ‘to recognize homosexuals’ and she made the link between the then familiar camp man-about-town and Captain Jones’ sodomy. This connection touched a nerve and he was vilified in the press and by the public. He was caricatured as ‘The Firework Macaroni’ and ‘The Military Macaroni” who was protected from the law by an establishment cover-up, saved from the gallows by his aristocratic community of fellow macaroni.

You could say the Macaroni Club has been hidden away in the back of the pasta cupboard of queer history. The forgotten fashion subculture was born out of the so-called “Age of Enlightenment”, a movement that sought tolerance, challenged religious dogma, and encouraged delving into the arts and sciences, but 18th century society evidently wasn’t yet enlightened enough to initiate any real discussion on gender identity.

The Macaroni fad would be closely followed by the ‘dandy’, considered a more self-made gentleman and outwardly a little more ‘manly’ in reaction to the excess of the macaroni, but still concerned with his own physical appearance, all the while working a more concealed queer agenda. It wasn’t until the trials and plight of Oscar Wilde (from 1895 onwards) that the cause for the recognition of homosexuality was even publicly highlighted, paving the way for gay rights in the face of injustice, ignorance and hatred.

The macaroni could not be a martyr for the queer agenda. Only aristocratic privilege had allowed the upper-class macaroni to enjoy and experiment with the queer identity in public without incurring the wrath of the heterosexual’s law. For the public it was little more than pure amusement, a dress-up opportunity and an ephemeral fashion moment, but for some, the Macaroni Movement may have been a brief opportunity in history to fly the flag of alternative gender identity.