2020 was called “the year of Karen”. The meme undoubtedly reached its height during the pandemic, but the concept itself is arguably nothing new. In the antebellum era, there was “Miss Ann”, widely used amongst the African-American community to refer to European-American women (or sometimes Black women) who were arrogant, “uppity” and condescending in their attitude, particularly when it came with racist undertones. The male counterpart was known as “Mister Charlie” throughout the Jim Crow era.

But what, exactly makes a Karen? The meme’s most common stereotypes include themes of entitlement, white privilege, racism and more recently, anti-vaccination beliefs. As one critic phrased it, “Punching down IS the definitive Karen behaviour,” while Black Twitter often uses the meme to describe women who “tattle on Black kids’ lemonade stands”. The Atlantic noted that “a man can easily be called a Karen” (Elon Musk was referred to as “Space Karen” on Twitter over comments he made regarding the effectiveness of COVID-19 testing). Kansas State University professor Heather Suzanne Woods, said a Karen’s defining characteristics are a sense of entitlement, a willingness and desire to complain, and a self-centered approach to interacting with others. Let’s take a look at a few other instances of possible “Karen” behaviour throughout history…

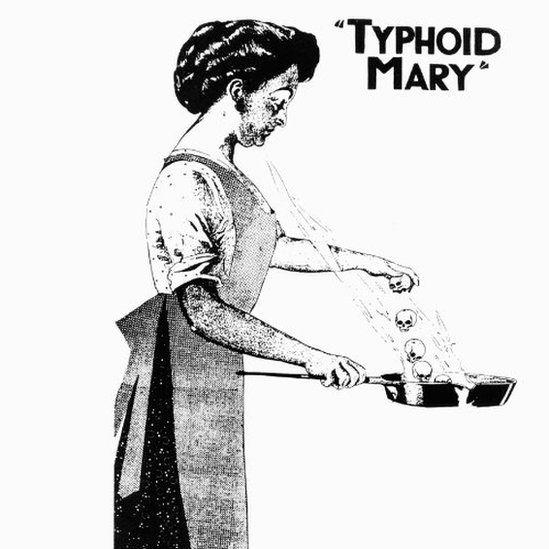

Mary Mallon, aka Typhoid Mary

“Typhoid Mary” was the first recorded asymptomatic carrier of typhoid, a bacterial infection that spreads through the eating and drinking of food contaminated by an infected person. Mary Mallon worked as a cook in New York City, and over seven years, she unknowingly infected 51 people. It’s believed that she did so mostly through her famous peach ice cream since high temperatures kill the bacteria, and ice cream would have done a pretty good job at preserving it. In 1907 she was forced into quarantine and released three years later under the condition that she changed her occupation. Though she agreed at the time, she soon changed her name and resumed her former occupation. In 1915, after disregarding advice to preserve the public health, Mallon started a massive outbreak at Sloane Hospital for Women.

Despite infecting almost everyone she worked for, she never believed she had the disease and refused multiple times to submit stool samples testing her for typhoid. It’s likely that she did not understand how she could be spreading the disease. When she was told she was spreading death and disease through her cooking and that investigators wanted samples of her feces, urine and blood for tests, she reacted violently and allegedly chased the lead investigator with a carving fork. Germ theory was still not widely accepted by the general public and this was the first ever identification of a typhoid carrier in the US. People could believe that an infected person could transmit the disease but found it hard to believe that an apparently healthy person could “carry” it. Mary Mallon herself said: “I never had typhoid in my life, and have always been healthy, Why should I be banished like a leper to live in solitary confinement?” She denied that she was responsible for anyone’s sickness or death and refused to recognise the authority of science or government to label her a menace to society.

Mary was an intelligent person who read the New York Times and Charles Dickens for pleasure but to have the blame for so many deaths laid at her door was seen by her as a conspiracy, a persecution by authorities looking for a scapegoat and an unwarranted insult to her personal hygiene and abilities as a cook. Her refusal to comply led her to be quarantined again until her death of stroke in 1938. Typhoid Mary infected “at least one hundred and twenty two people, including five dead.” Drunk History did a terrific episode on Typhoid Mary.

Leni Riefenstahl

In the above photograph, a woman is caught on camera after witnessing SS soldiers slaughter 20 Polish people in 1939. Her horror is apparent, and it would not be surprising, if it weren’t for the fact that she was Hitler’s personal film director for Third Reich propaganda and she worked closely alongside the führer long after this photo was taken. Her name was Leni Riefenstahl.

The following summer, Leni wrote to Hitler:

“With indescribable joy, deeply moved and filled with burning gratitude, we share with you, my Führer, your and Germany’s greatest victory, the entry of German troops into Paris. You exceed anything human imagination has the power to conceive, achieving deeds without parallel in the history of mankind. How can we ever thank you?”

She started out as an actress in the 1920s and later became one of the few women in Germany to direct a film during the Weimar Period when she made her own film, Das Blaue Licht (“The Blue Light”), earning her the Silver Medal at the Venice Film Festival. The film however was not without its critics, many of whom were Jewish. Upon its re-release in 1938, credits were removed for the co-producer and co-writer of the film, both of whom were Jewish. Hitler saw the film and thought Riefenstahl epitomized the perfect Aryan female.

Charles Moore of The Daily Telegraph wrote, “She was perhaps the most talented female cinema director of the 20th century; her celebration of Nazi Germany in film ensured that she was certainly the most infamous.”

After the war, Riefenstahl was arrested, but was not charged with war crimes. Throughout her life, she denied having known about the Holocaust but German war crime courts later found that in 1940, she filmed in Krün near Mittenwald using unpaid Roma concentration camp prisoners as extras. Riefenstahl sued a documentary filmmaker Nina Gladitz, for saying she personally chose the extras at their holding camp.

Post-war, Leni continued working in media at a magazine where she got to cover the 1972 Olympics, photograph Mick Jagger and spent years documenting Africa and underwater exploration.

In 2000, Jodie Foster was planning a biographical drama on Riefenstahl, then seen as the last surviving member of Hitler’s “inner circle.” Critics had to caution Foster against romanticising the director. When she turned 100 years old in 2002, she was taken to court by a Roma group for denying the Nazis had exterminated Romani.

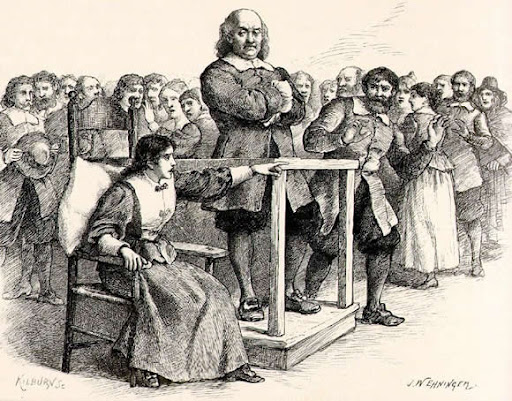

Ann Putnam, Jr.

Of the 62 people Ann Putnam Jr, accused and testified against during the Salem Witch Trials, 20 were executed. One victim was tortured to death, and one died in prison. She was one of the most important key witnesses in the infamous trials. Sixteen years after testifying, she publicly apologised, claiming she was “deluded by Satan.”

Thomas Putnam Jr.’s eldest daughter named more people than anyone else. There is a long history of the Putnam family’s decline in local politics and a number of family and community feuds that pit the Putnams against a lot of other people, many of which lined up with her accusations. Thomas Putnam Jr. had the most to gain from a lot of the accusations and it’s speculated his daughter did a lot of finger pointing at his behest.

A total of 177 people were accused of witch craft and as other villages got caught up in the midst of the hysteria, accusations were made believable if Ann Putnam Jr, Abigail Williams, Mercy Lewis and Elizabeth Hubbard – known as “the Circle girls” – supported it. Accusations created power. Once the accusers held that power, they couldn’t be targeted.

After the trials, Ann’s parents died suddenly in 1699, and she was left to raise her seven siblings. When she later wanted to join the Salem Village Church, she first had to apologise. The church forgave her and accepted her as a member. Her apology is much more of a non-apology since it seems to be more about protecting her local standing by fighting the stigma of her involvement. Still, she is the only accuser to seek forgiveness, but she placed the blame on Satan and not herself, other accusers, or the family members that pushed her to accuse.

Josephine Jewell Dodge

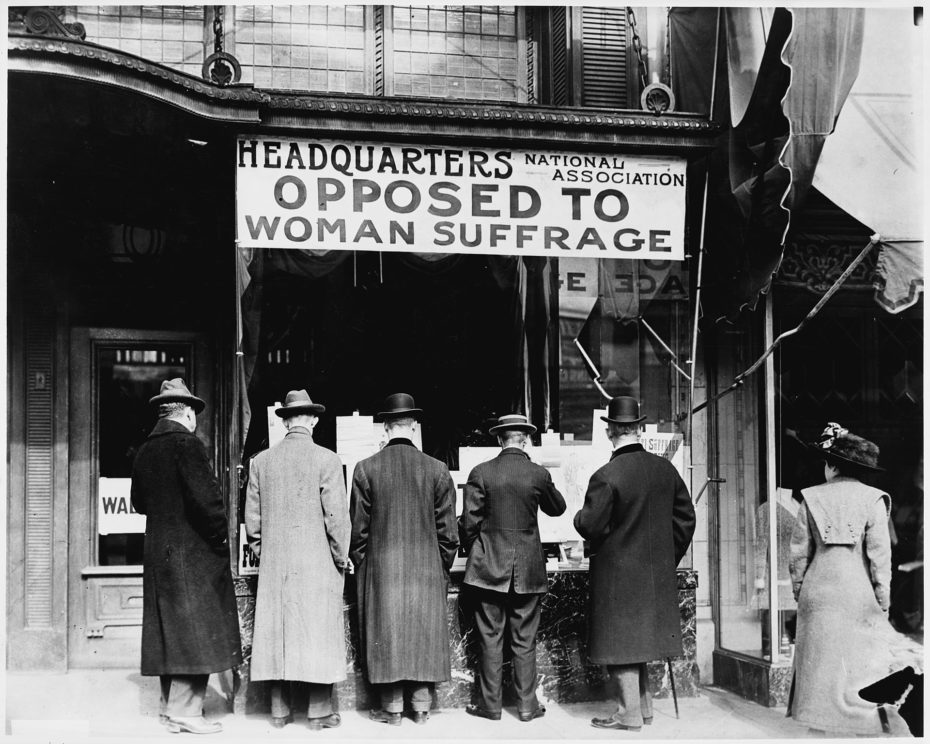

Womankind have the suffragettes to thank for our ability to stand at the polls (or be on the ballot) today, but the late 19th century had plenty of opposition — not just from men, but from other women. Who were these women who actively spoke out against a woman’s right to vote? “Generally women of wealth, privilege, social status and even political power,” political science profressor Corrine McConnaughy told NPR. “In short, they were women who were doing, comparatively, quite well under the existing system, with incentives to hang onto a system that privileged them.”

Josephine Jewell Dodge was the daughter of the U.S. minister to Russia, attended Vassar College and married into a prominent New York family. She became a leading anti-suffragist Dodge and founded a group called the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, which had it’s own official headquarters at 35 West 39th Street in New York City. She’s famous for her writing “The Lesson that Came from the Sea. The sinking of the Titanic in 1912 inspired a flood of articles on seemingly every aspect of the disaster. One of the oddest appeared in The Woman’s Protest, a journal dedicated to opposing women’s suffrage. Josephine Jewell Dodge noted that when the ship started going down, the cry that went up was not “Voters first!” but “Women and children first!” Dodge wrote that “in acquiescing to that cry the women admitted that they were not fitted for men’s tasks. They did not think of the boasted ‘equality’ in all things.” The disaster, she wrote, “tends in its terribly grim way to point out the everlasting ‘difference’ of the sexes.”

Josephine’s efforts received admiring coverage in The New York Times at the time. A variety of rose was named for Dodge and was grown especially to decorate tables at an anti-suffrage meeting in New York’s Hotel Astor.

The Stepford Wives of Levittown

Levittown was to be a utopian, American suburb, created out of nothing; a fully planned, complete town for about 70,000, living in pre-designed homes that came out of a catalogue. But with owning utopian property apparently comes a sense of entitlement. In 1957, homeowners sold their Levittown property to an African-American couple, William and Daisy Myers. Ugly newsreel footage shows the shameful race riots that led to police clampdown in the supposed genteel, cookie-cutter small town. And just have a listen to one of the housewives of Levittown speak about her new neighbours and the neighborhood’s overall diversity:

Levittown’s mission to create the idyllic, all-white American town would also give rise to the suburban angst found in novels such as Richard Yate’s Revolutionary Road. Yates wrote of, “a blind, desperate clinging to safety and security at any price, as exemplified politically in the Eisenhower administration and the McCarthy witch hunts.”

Urban historian Lewis Mumford was less kind; “the suburb served as an asylum for the preservation of illusion. Here domesticity could prosper, oblivious of the pervasive regimentation beyond. This was not merely a child-centered environment; it was based on a childish view of the world, in which reality was sacrificed to the pleasure principle.

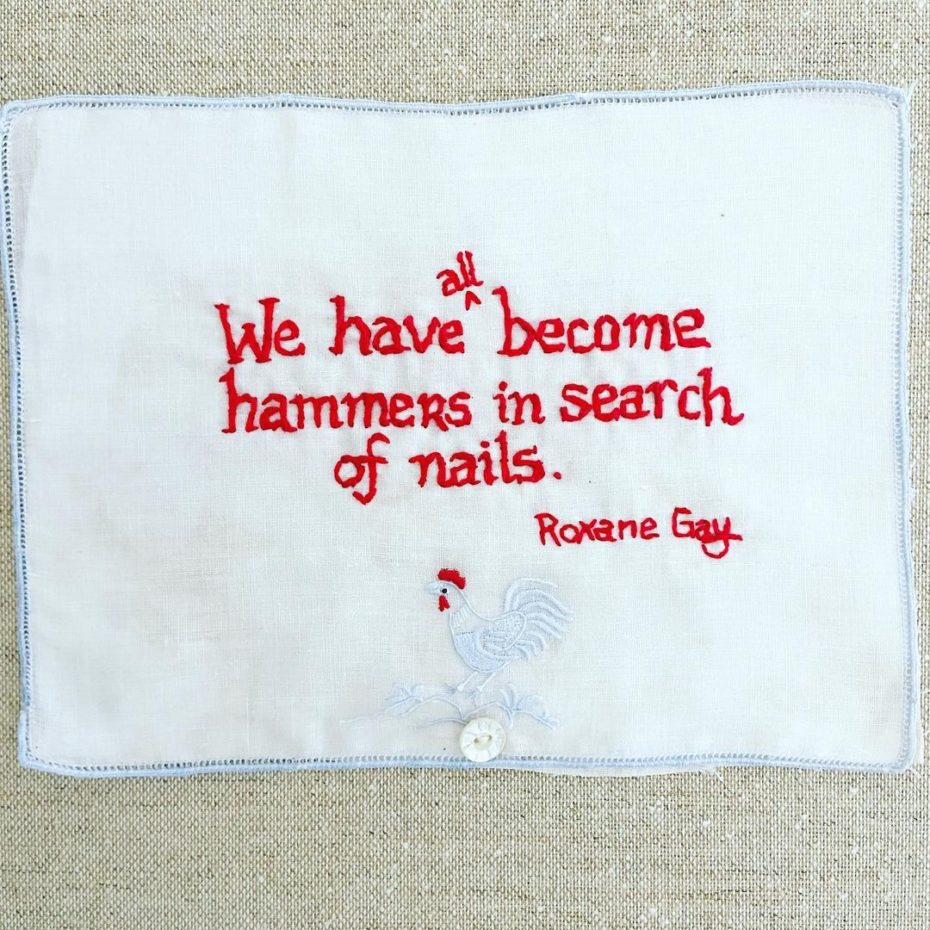

The Karen has survived several “rebrandings” throughout history and soon enough, she (or he) will go by another name. The behaviour is nothing new, but perhaps how we react to it speaks to our future as a society. How can we better react to the “Karen” without indulging in our collective need to destroy one another in this era of 15 minutes of shame?

As the The Atlantic points out, in Simone de Beauvoir’s words, the Karen may be “half victim, half accomplice, like everyone else.” As challenging as it may be to show sympathy, perhaps channelling one of literature’s most famous characters might be helpful. Atticus Finch in Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird is tasked with defending Tom Robinson in his trial where he is wrongly accused of raping Mayella Ewell. Finch is able to recognise his accuser’s real trauma, exposing that after Mayella made sexual advances toward Tom, she was subsequently beaten by her father. The Karen (in this case Mayella) represents a wounded, aggressive and frustrated person in society who feeds off anger and resentment. To quote Walt Whitman, “Be curious, not judgemental”. Appreciate it’s perhaps not the Karen’s fault and see it for what it is. Martin Luther King Jr. himself referenced Atticus Finch in Why We Can’t Wait, his book in which he spoke about the importance of upholding principles through nonviolent action. Aside from some recommended reading, if all else fails – what’s the best way to deal with the Karen, particularly online? Disengage, back away and unplug.