For hundreds of years, the term “computer” was a job title for a human before machines took over the job, and in the late 19th century, computers weren’t just human, they were mostly women. An English Countess and Victorian mathematician, Ada Lovelace, is regarded as the first computer programmer and by World War II, American industrialists were measuring the power of early computer devices in “kilo-girl” hours, not in megahertz or teraflops. It was Grace Hopper who developed the first compiler, Hollywood actress Hedy Lamarr invented the basis for modern Wi-Fi, and African-American female mathematicians like Katharine Johnson were the hidden force behind sending the first man to the moon, playing a critical role in America’s pursuit of space exploration. In short, without women, computer science might not exist as we know it today.

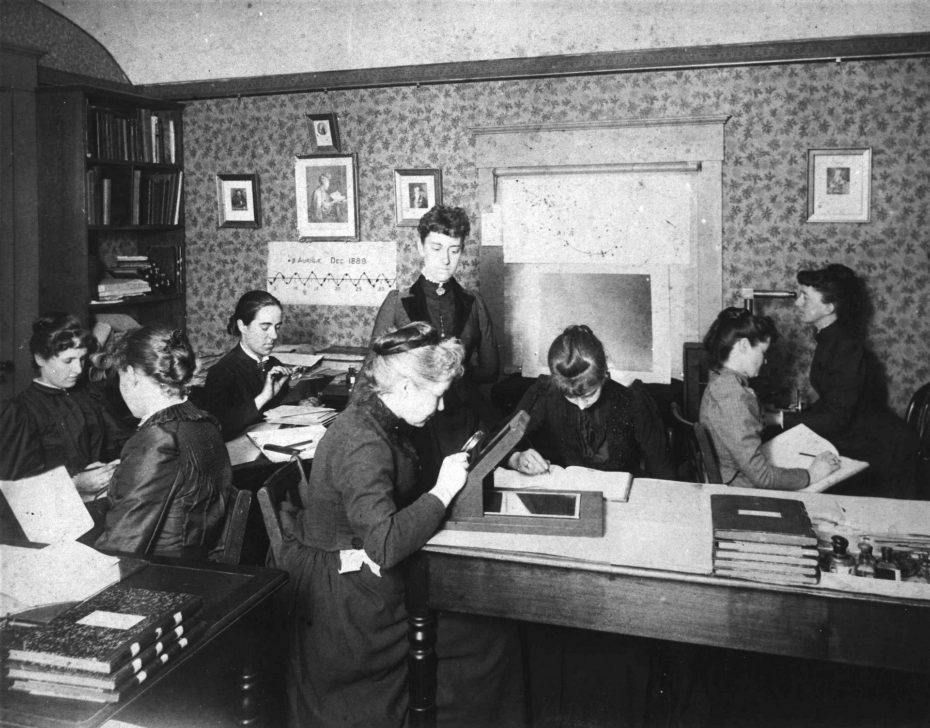

Let’s take it back to the scientists of yesteryear in the field of astronomy, navigation and surveying, who were hiring teams of well-educated men to repeatedly compute calculations too tedious for them to drudge through themselves. However, by the late 19th century, these scientists realised that hiring women could be a cheaper alternative, and with the gradual rise of women pursuing higher education, particularly from middle class backgrounds, more young women than ever were well-versed in mathematics.

Edward Pickering of the Harvard Observatory decided to hire a team of women after becoming increasingly frustrated with his male assistants. He declared that his housemaid, Scottish immigrant Williamina Fleming, could do a better job, so he hired her along with a team of female “computers” at half the rate he would pay for men. The team of ten women, which included relatives of respected astronomers or observatory staff, soon discovered how to measure distances of stars. They became known as the Harvard Computers. Pickering’s housemaid, Williamina, became the first female American citizen to be elected to the Royal Astronomical Society in 1907.

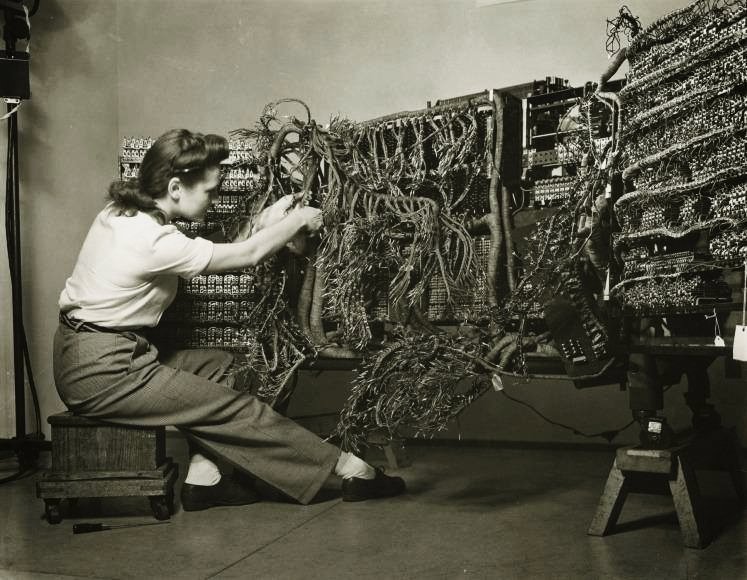

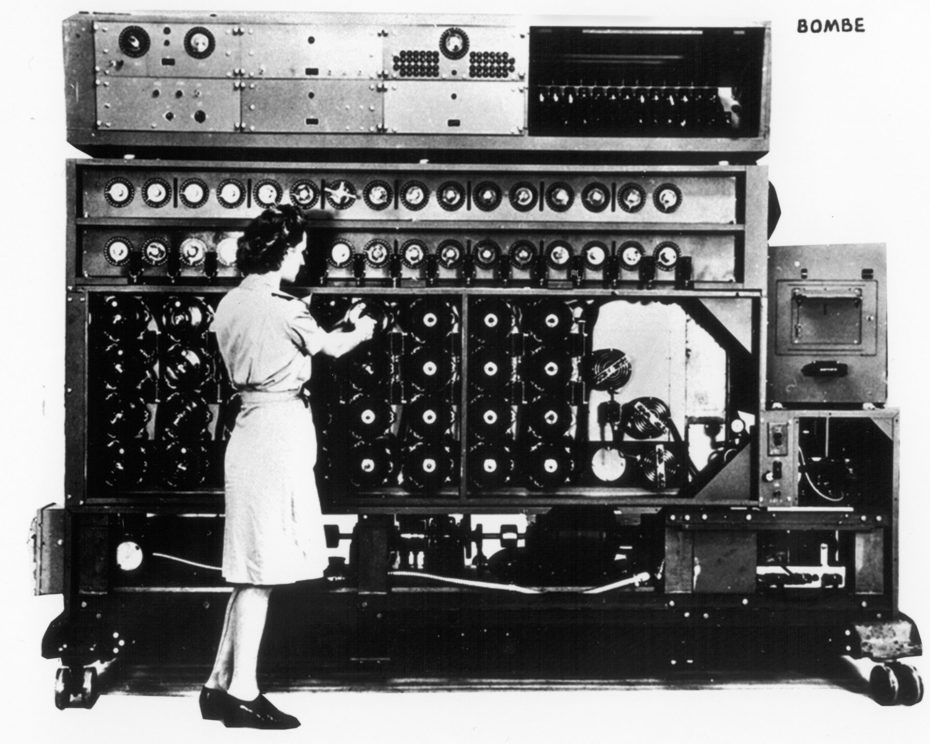

By WWII, with all hands needed for the war effort, the Army hired a group of women computers to calculate artillery trajectories. These women worked as support to the engineers and were brought on because computing was still thought to be menial and low status work; too dull for the highly educated men on staff who wanted more exciting jobs. This disregards the fact that in order to solve these equations these women would have to re-work the same calculations over and over again for hours. Former computer, Marilyn Heyson, recalled in an interview that the job was intellectually interesting, but a marathon. These calculations not only required great mental endurance, patience, and attention to detail, but advanced mathematical skill.

In 1939, Barbara “Barby” Canright in 1939 was the first woman to be hired as a female computer at t NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Calculating everything by hand—from how many rockets were needed to make a plane airborne to figuring out how to get a 14,000 pound bomber in the air—fell squarely on Barby’s shoulders. More women would be hired to help Barbara in the years to follow, including Melba Nea, Virginia Prettyman and Macie Roberts, who would become supervisor of their department of human computers by 1942, later dubbed the “rocket women”. Roberts made the decision to hire only women in their department as she felt that men wouldn’t take direction well from a female boss and would throw off the cohesion of the team.

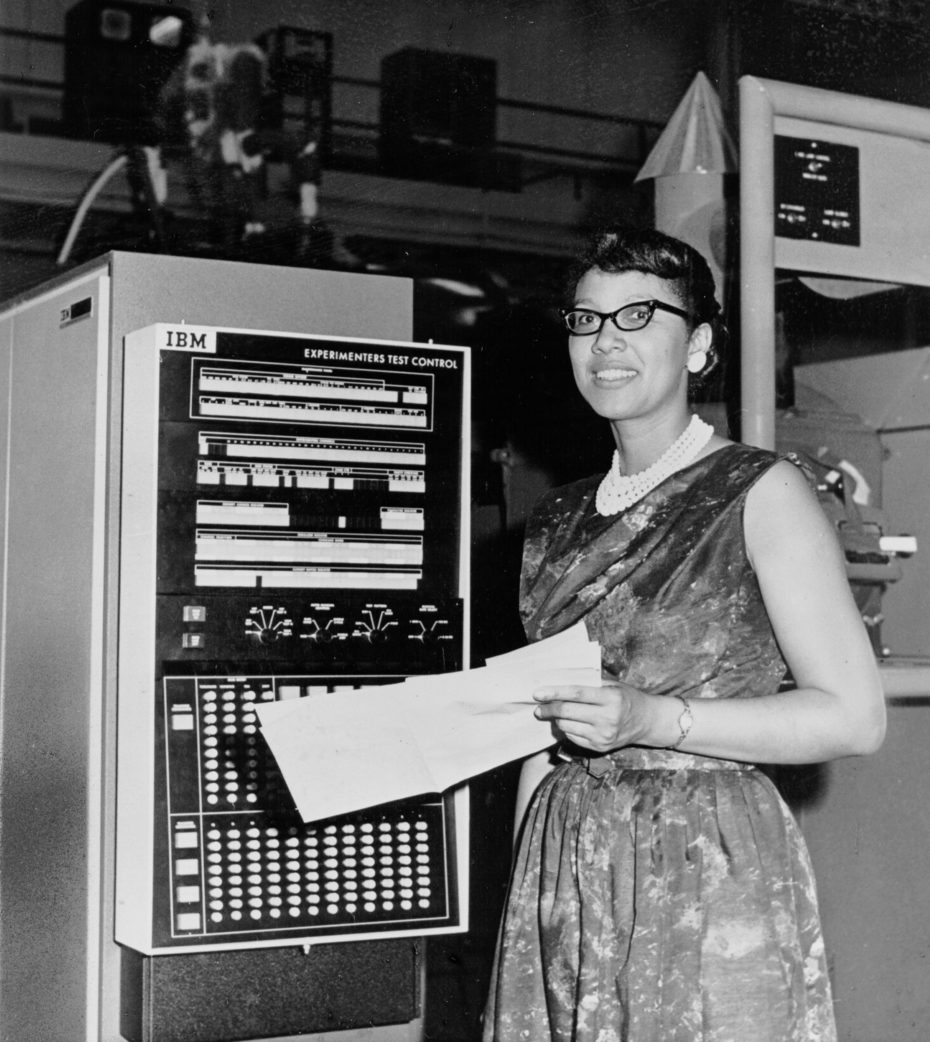

Employment opportunities that had previously been closed to many marginalized groups were now open. Asians, African Americans, Jews, and polio survivors were all hired on as computers during the mid century. What was once viewed as a cheap alternative to hiring white men, actually opened the door for women and minorities in the STEM (Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields.

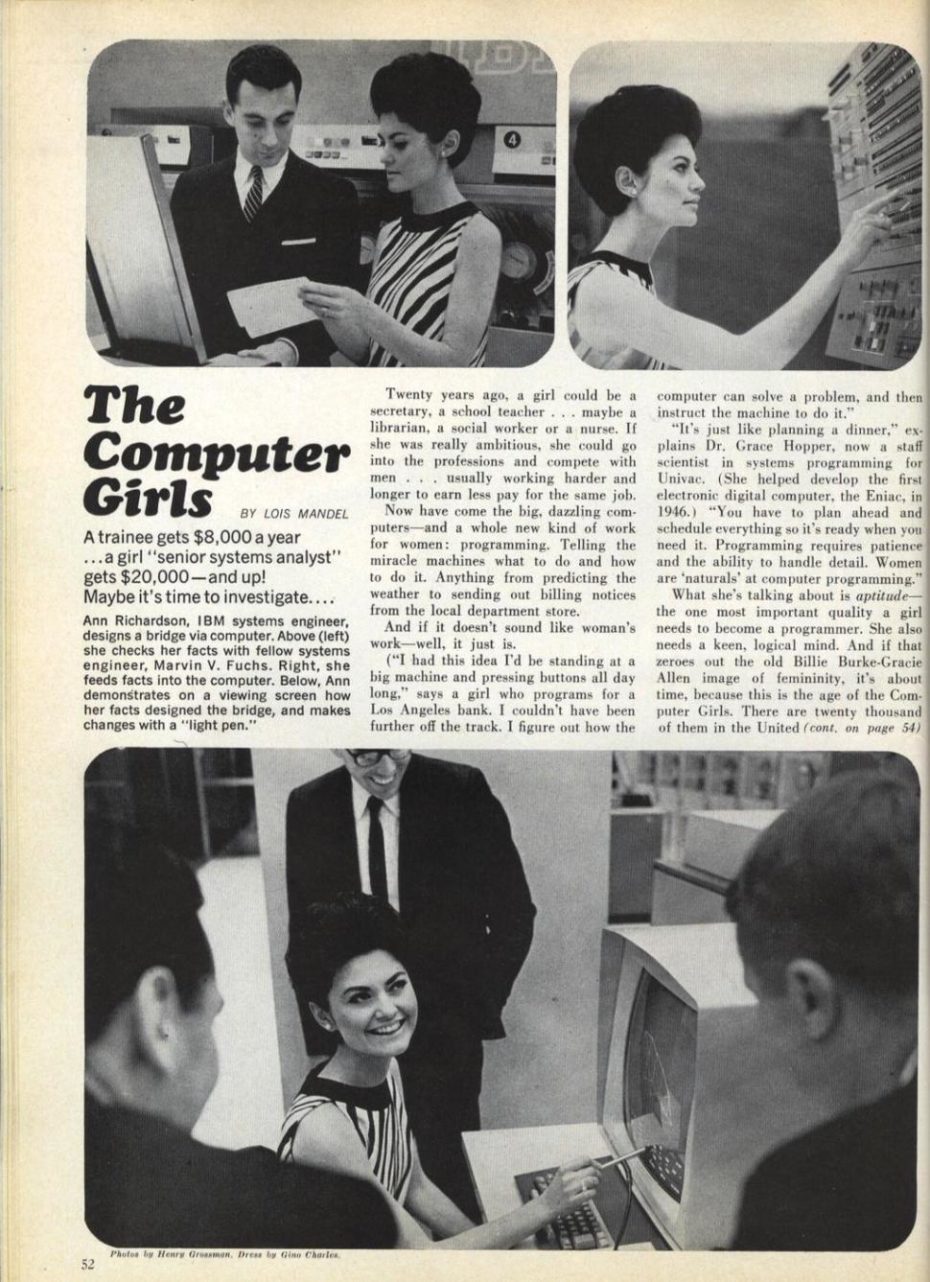

Inside America’s secret atomic city known as the Manhattan Project, women were hired as computers to calculate hundreds of iterations of complex formulas regarding nuclear fission. Computer programming pioneer, Dr. Grace Hopper, who invented on of the first linkers, also solved an equation for the Manhattan Project, which would make the atomic bomb function. She said programming was “like planning a dinner. You have to plan ahead and schedule everything so it’s ready when you need it.”

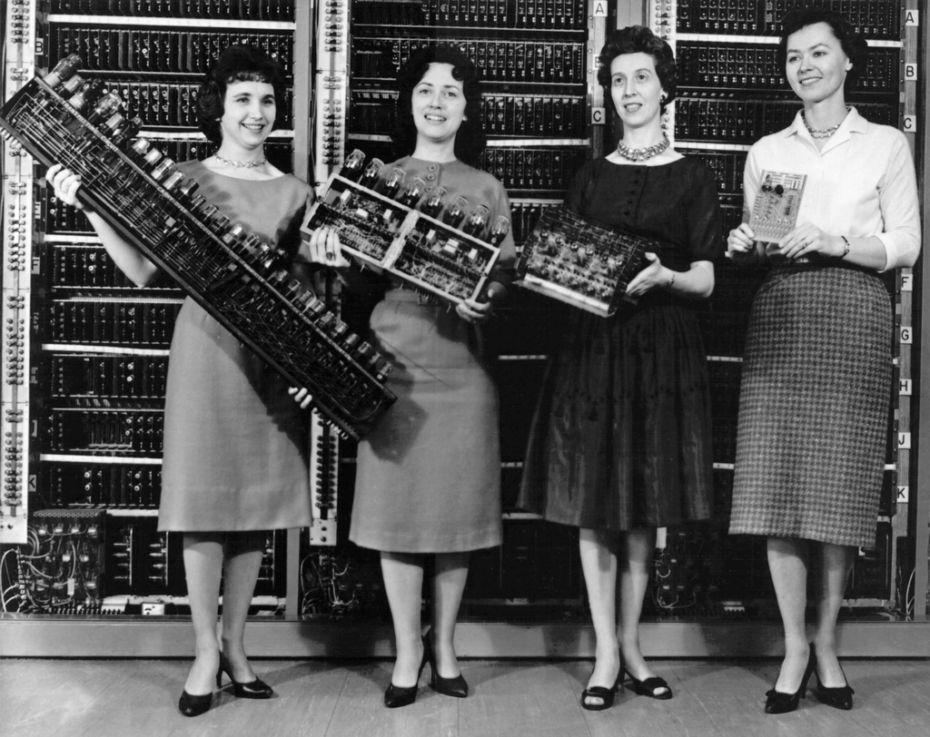

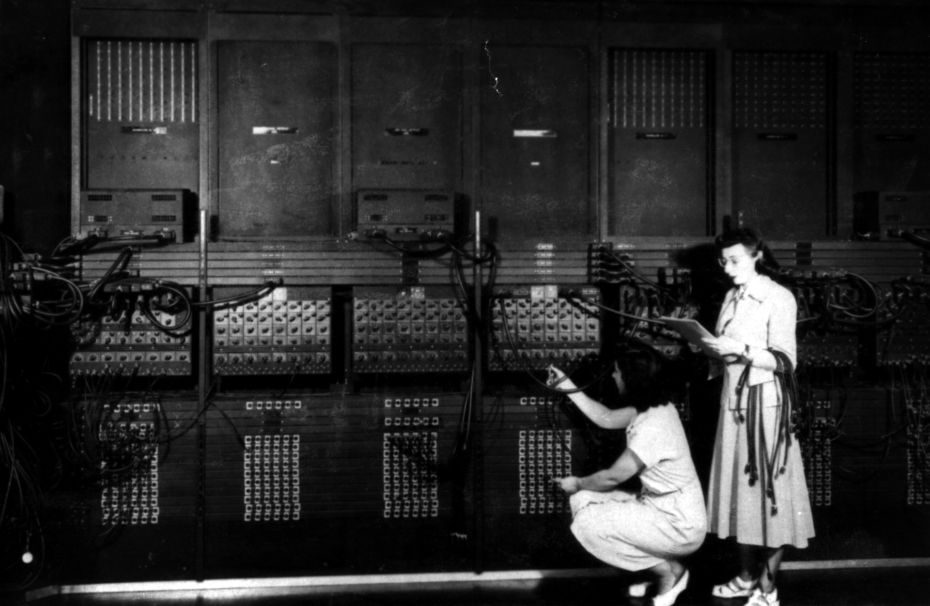

In 1946, when the world’s first all-electronic, programmable computer known as ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) was brought online to calculate artillery firing tables for the United States Army, it was programmed by a team of six brilliant young women, all without the use of programming languages or tools. ENIAC weighed more than 60,000 pounds, covered 1800 square feet of area, consumed 150 kilowatts of power, and cost $500,000 to build.

Thanks to the newly diversified career fields, practices specifically benefitting female employees were enacted that ensured an unprecedented job security never before experienced by female workers. This was because the initiative was taken by the women in these departments to enforce policies that would consider the needs of other women.

In other career fields — particularly male dominated fields — hiring a young, married, childless woman was viewed as risky. What if she had children? Surely she couldn’t tend to both her home and her job at the same time?

At this time, maternity leave did not exist, and as a result, often women who were due to be mothers were not offered re-employment after leaving to give birth. Sometimes, employers did not want to risk hiring young married women at all.

Helen Ling, who worked on Macie Roberts’ team at NASA, was one such woman who extended opportunities to women who would have otherwise never had a chance in these fields. Once she became a supervisor she purposely hired women who had no engineering background and encouraged them to attend night school. She also extended re-employment to women after they left to give birth, enforcing her own unpaid maternity leave.

The 2016 Academy Award nominated film Hidden Figures followed the lives of three real Black women who worked as human computers during the space race. Dorothy Vaughan was hired at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Virginia in 1943 and by 1951 she became the first African American manager. Like women before her, Vaughan began hiring other women into her departments. That same year, Mary Jackson was hired and a year later, Katherine Johnson would join the team as well. After only two weeks in the segregated computing section, Johnson was transferred to Langley’s Flight Research Division and offered to calculate how to make NASA’s space capsule land in a certain area by working the calculation backwards in order to determine when it should take off. Her calculations were integral to some of NASA’s biggest projects, including sending the first man into space, sending an astronaut into orbit around the earth, the launch of Apollo 11, and ensuring Apollo 13’s safe return after it’s malfunction in space.

Today, it’s not unusual to be able to name women astronauts or rocket scientists, but it’s still rare. Women were hired into the field of space science on discriminatory practices of underpaying and underestimation today, discrimination persists in new forms. Women are four times more likely to leave the field than their male counterparts.

A study done by William Flaherty at Williams College reported that women cited barriers of hiring biases, lack of assigned telescope work, higher workloads, and sexual harassment as reasons that women left their careers prematurely. The discrimination is even greater for women of color who are earning degrees in astrophysics at a much lower rate and face even more systemic barriers due to the intersectionality of race and gender.

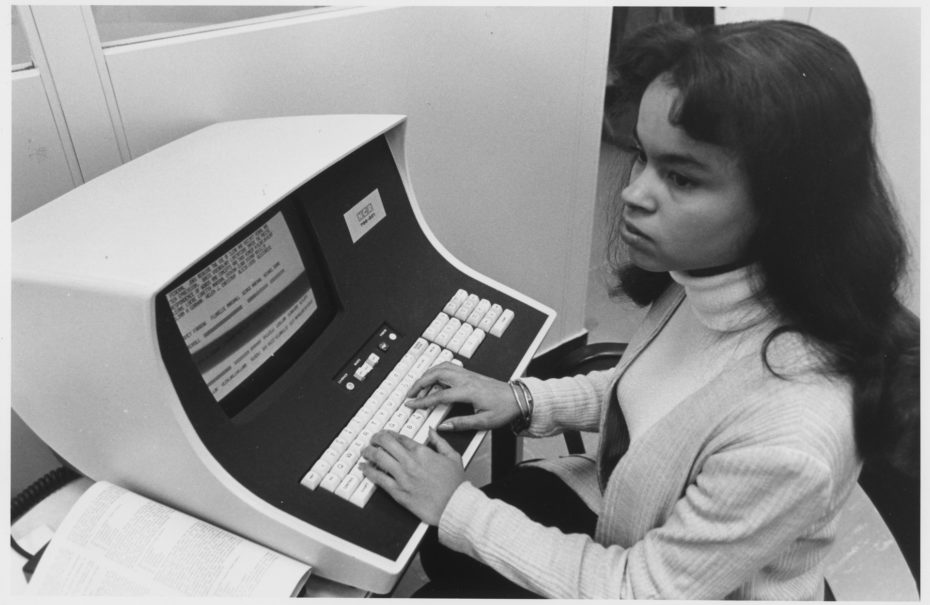

Before it became male-dominated, computer programming was a promising career choice for women, who were considered “naturals” at it. Even up until the 70s and 80s, women spearheaded programming as a profession, but sometime around the mid 1980s, the personal computer entered the picture and was heavily marketed as a boy’s toy and families typically placed the computer in the brother’s room within the household.

“This idea that computers are for boys became a narrative,” notes NPR. “It became the story we told ourselves about the computing revolution. It helped define who geeks were, and it created techie culture.”

Soon enough, computer programming shifted over to being a male-dominated field the way most industries do: men in power gave positions and promotions to other men, keeping women at low menial rank and salary regardless of talent and experience, and here we are today, trying to get women back into STEM fields, but doing very little about the biased hiring practices that made it this way.

That said; the odds facing women in this field are not insurmountable especially with efforts being made to make the prospect of a career in STEM more attractive to women and girls with initiatives like Girl Start and Girls Who Code. The Recurse Centre in New York City is a free computer programming school that offers $10,000 fellowships for women, trans, and non-binary programmers. Some computer programs are making an effort to switch up their teaching style by making their program more interactive and student oriented.

In Harvey Mudd’s computer science program, half of the faculty is female. According to Mudd: “It definitely helps having role models and enthusiastic faculty members who are women.”

The predecessors for the current generation of women in astrophysics laid an admirable foundation. With the current aim of astronomy and astrophysics shifting towards a goal of ushering women and girls into these fields of study; it will be up to the future generations to continue to move the goalpost further and build something these women would have been proud of.