Secret college societies have lurked in the shadows of the Ivy League since the 19th century, and the rumours and whispers about what happens behind closed doors only adds to the mystery and allure, but there was one secret faction in particular which managed to keep itself hidden behind Harvard’s prestigious reputation. For over 80 years, one of the darkest moments at one of America’s most prestigious institutes of higher learning went unreported. In 1920, a student’s suicide led to an ad hoc secret court at Harvard University investigating homosexual activity on campus. The tribunal that permanently expelled eight students and ended an assistant professor’s career at Harvard, was known officially amongst its participants as the “Secret Court”. Its files and records were ironically stored under that name and remained undisturbed in the university archives until 2002 when the incident was finally unearthed by a researcher from the school’s undergraduate daily newspaper. It became a stain on the history of the Ivy League university, but also an opportunity for members of the LGBTQAI+ community to fight the homophobia that is still very much present today.

This story goes back to May 13, 1920 when Cyril Wilcox, a Harvard undergraduate, committed suicide at his parents’ home. Wilcox had withdrawn from school, citing health reasons, and was struggling academically. The night before he killed himself, Wilcox had confessed to his brother George Wilcox, who had also attended Harvard, that he was having an affair with an older man in Boston named Harry Dreyfus.

After the suicide, George Wilcox found letters from two of his brother’s peers, giving him the impression that there was a network of homosexual students at the university. George confronted Dreyfus and beat him until he revealed the names of three other men. Later that same day, he met with Harvard’s acting dean, Chester Noyes Greenough.

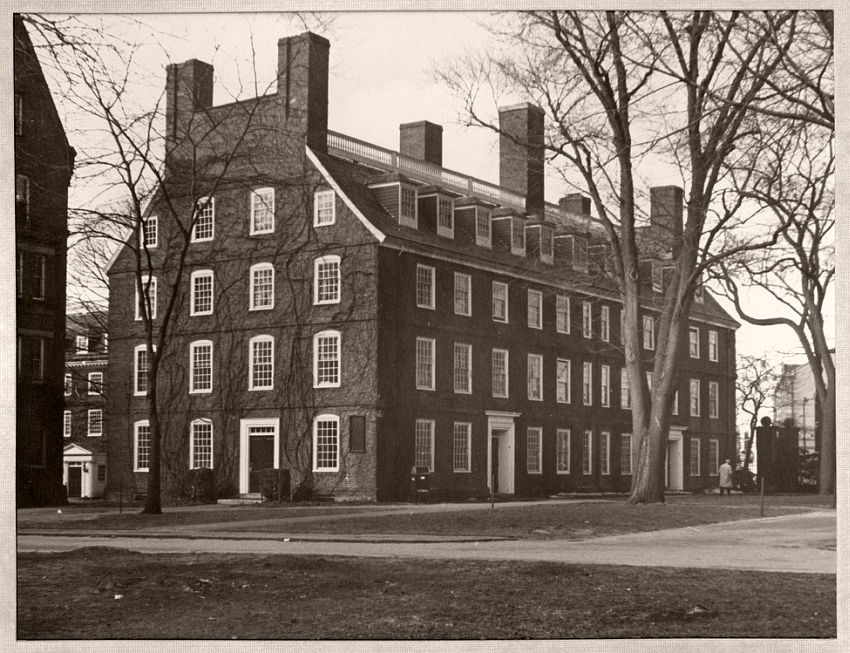

Greenough discussed with Harvard President Abbott Lawrence Lowell and they decided to bypass the due process usually required for student disciplinary hearings and set up a clandestine tribunal just a day after Wilcox’s testimony. One member was Robert I. Lee, a professor of hygiene who was also tasked with students’ physical examinations and therefore would be accustomed to asking questions about sexual activity. It also included two assistant deans and the administrative officer who handled student discipline and conduct. They reported directly to President Lowell, who had the final ruling.

An unsigned letter was sent to Dean Greenough at the start of the investigation. The writer, describing himself as a Harvard junior, said that Cyril Wilcox had become friends with peers who “committed upon him and induced him to commit upon them ‘Unnatural Acts.'” Unable to find the “strength of character” to leave this group, he committed suicide. The letter also named Ernest Roberts, one of Wilcox’s correspondences and the son of a former congressman, as both the leader of this circle and as being directly responsible for the suicide.

The court began on May 27th of 1920, with the trial’s witnesses receiving vague notes summoning them to appear in Dean Greenough’s office. Only transcripts of the proceedings remain, leaving the tone of the more than 30 interviews unknown, but witnesses were asked deeply personal questions concerning their sexuality. The court garnered not only a list of parties and activities taking place on campus but also at local Boston businesses frequented by queer people. Out of fear of punishment or because of testimony gained from others that was used against them, many revealed intimate details about themselves. In the end, the eight expelled students were forced to not only leave campus, but the city of Cambridge immediately. They were be ousted without formal explanation for their departures, and not only denied recommendation letters, but Joseph Lumbard, one of the convicted students, found himself “blocked by negative responses” from Harvard when applying to Amherst College, Brown University and the University of Virginia. Dean Greenough wrote to all of their families, not saying exactly why their children were expelled but encouraging parents to ask them for an explanation. Parents’ responses were varied: Lumbard’s father wrote back to challenge his son’s “extremely unjust treatment,” while the father of another student wrote that hoped this would spell the end of his “evil practices”.

Somewhat surprisingly, the case garnered no public attention, despite the fact that another suicide might have brought the incident to light. Eugene Cummings, who studied dentistry and was one of the expelled students, killed himself soon after the inquiry ended. He was from the same town in Massachusetts as Wilcox and they had been friends. An article in the Boston American reported that a “mentally unbalanced” Cummings had told friends about the inquisition, describing it as a room “shrouded in gloom.” But Secret Court member Robert I. Lee dismissed Cummings’ story and it received no further coverage. Some of the students were able to overcome the mark on their records, pursing jobs ranging from a psychiatrist to a Broadway producer to an interior designer, but not without challenges. A third student committed suicide a decade later and an FBI investigation almost halted the career of one who became a United States Circuit Judge.

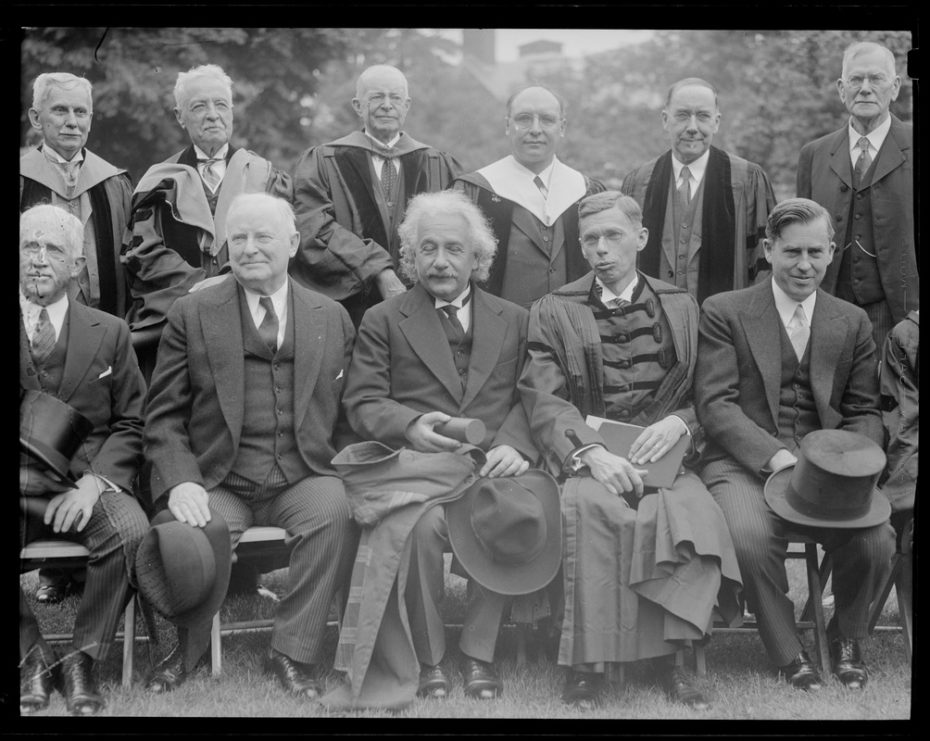

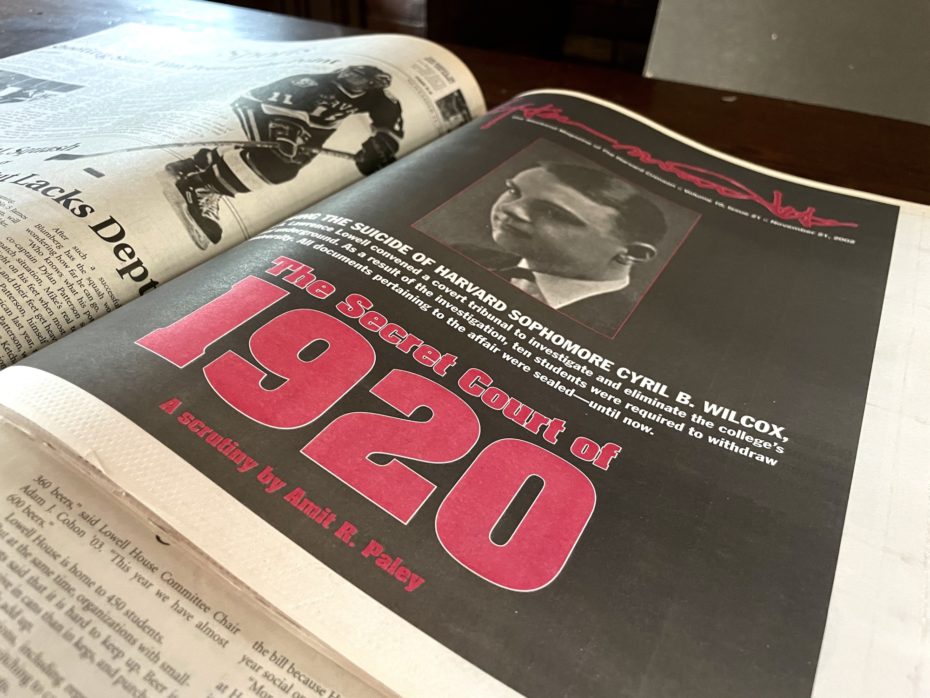

It wasn’t until 2002 that Amit Paley, a researcher at the Harvard Crimson, came across the “Secret Court” box in the school’s archives. The Crimson staff had to campaign to get access to the records but eventually had some 500 documents released to them and on Nov. 21, 2002, Paley published an article about the case. Although Harvard had the names of those under investigation redacted, many were identified through research by Crimson journalists. The article includes a quote from then University President Lawrence Summers in 2002: “These reports of events long ago are extremely disturbing. They are part of a past that we have rightly left behind.”

The Secret Court fits within a larger discussion over Harvard’s past actions and how they’ve continued to impact the institution, from supporting enslaved labor to the sexist barriers faced by female professors and students. Only a week after the revelations in the Harvard Crimson, a rival conservative campus magazine, the Harvard Salient, published an editor’s letter written by a junior student in support of the university’s actions in 1920, calling the court’s work “a very appropriate disciplinary move,” while imploring that Harvard “reestablish standards of morality”. The letter, published in the biweekly magazine best known for its parody of Harvard’s politically correct culture and counts Wall Street Journal and New York Times columnists as former editors, went on to note that “such punishments would apply to heterosexuals, of course, but even more so to homosexuals, whose activities are not merely immoral but perverted and unnatural.”

Since the discovery of the Secret Court, the student body at large has worked to raise awareness surrounding homophobia in the Ivy League. In 2012, Lady Gaga was invited to Harvard to launch the Born This Way Foundation. In 2020, the centennial anniversary of the Secret Court of 1920 refuelled the drive to make the university a safer space for its LGBTQA+ community, with student leaders forming the Secret Court 100 initiative. They’re demanding institutional recognition of past actions, including giving honorary posthumous degrees to the expelled students, and addressing current issues around inclusive mental health services, curriculum and housing. The Secret Court’s legacy has further extended beyond campus, with an off-Broadway play called “Unnatural Acts” and a podcast starring actor Zachary Quinto. (Author William Wright also wrote a nonfiction book that dives deeper into the incident).

And as for the researcher Amit Paley, who unearthed it all. He is now the CEO of the Trevor Project, the world’s largest suicide prevention and crisis intervention organization for LGBTQAI+ young people. On the 100th anniversary of the Secret Court, he told the Harvard Gazette, “It’s an attack on their dignity; it’s an attack on their memory, their lives, to not have the truth of who they were be told.”