Buried by the elitist art establishment, hers must be the art world’s best kept secret this century. This is the story of a possessed, prodigious painter who prolifically created art that looks so modern it looks more at home in the 21st century; the story of a spiritually-minded artist trying to grasp the wonders of the natural world, who dabbled with the occult through séances. A woman who dared to trespass where male artists were calling the shots in the 19th century. A woman who was eons ahead of her time. Her name was Hilma af Klint.

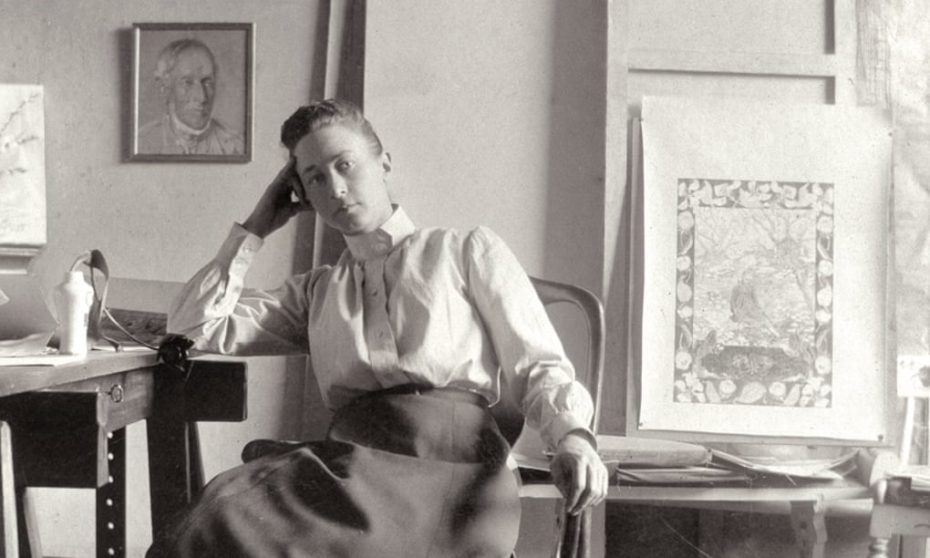

It’s over a century ago that Hilma af Klint had furiously been labouring away in her native Sweden, a petite woman dressed in black with a comely demeanour and piercing blue eyes, patiently concocting her egg yolk tempera, navigating across the floor an enormous canvas with her tiny feet. What she left behind has lain dormant and undiscovered for so long, it has baffled art historians who are still dealing with this this incidental but potentially mammoth piece of Scandinavian modern art dynamite. Those in the know ponder whether art history books have missed a turning, and should in fact be rewritten.

Hilma af Klint (1862-1944) painted groundbreaking abstract art in 1906, allegedly before Mondrian, Malevich and Kandinsky staked their claims as being the pioneers of Western abstract art. The significance of this cannot be overstated. Another noteworthy and rather juicy piece of this puzzle is that those very works by Hilma af Klint were remarkably similar to those of the ‘fathers’ of abstract art, as if there had been some collaboration between or at the very least, exchanging of ideas between likeminded contemporaries.

Let’s try putting Hilma af Klint’s fascinating life into perspective, as it’s clear there are more than a few controversial sub-plots to her tale. She was born to an aristocratic, Protestant family, her father was ‘Captain’ Victor af Klint, an admiral, mathematician and occasional violinist. She spent her childhood summers engrossed in nature at the family’s manor on the idyllic Island of Adelsö at Lake Mälaren. From the outset, she was a curious and gifted child who showed a keen interest in botany, mathematics and the visual arts.

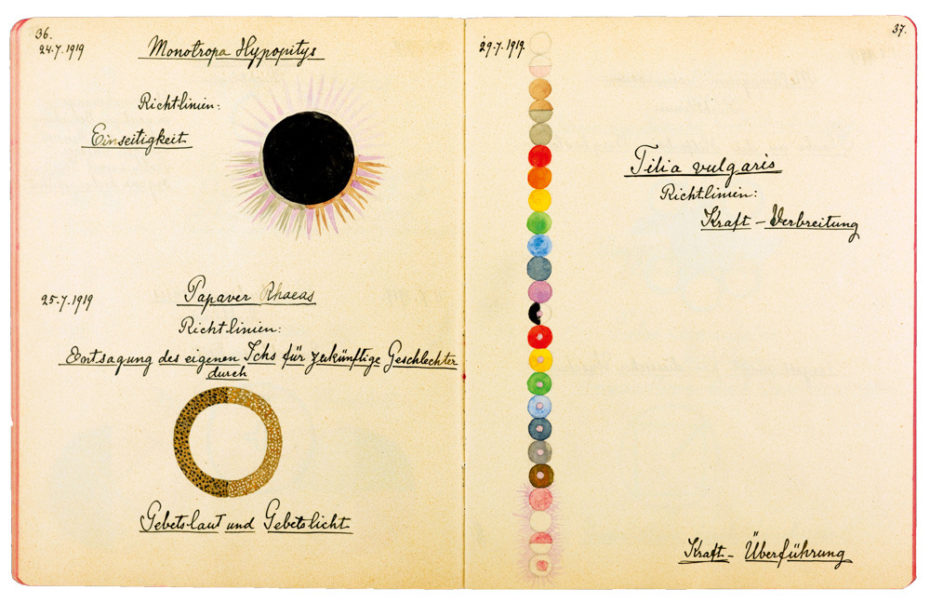

When the family relocated to Stockholm, she studied landscape and portraiture painting at the Tekniska Skolan and thereafter at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. She excelled and was offered a scholarship and residency at the Atelier Building owned by the Academy of Fine Arts, a melting pot of cultural and intellectual activity, a place where visiting painters from abroad would often pause for a visit. All the while, she managed to support herself financially with her meticulous and traditional botanical drawings, sketches and paintings.

During this time she became engrossed in Helena Blatavsky’s Theosophy, a philosophy based on supernatural forces and often associated with occultism. This was neither unusual nor uncommon at the end of the 19th/ early 20th century when the Spiritualist Movement and the practice of séances thrived during the Victorian era. In fact, Kandinsky, Malevich, Mondrian, Yeats and Nabis were also keen proponents of the Theosophical movement. It was a time of never before seen scientific discoveries comparable to the supernatural: Heinrich Herz discovered electromagnetic waves in 1886 and Wilhelm Röntgen generated X-rays in 1895. Hilma af Klint was captivated by the new sciences and tried to make sense of them in her own curiously mathematical, musical and artistic brain. She seemed to have an aptitude for spotting recurring patterns in nature, to abstractify and simplify, eternally seeking hidden reason and meaning.

Hilma af Klint’s interest in the spiritual side of things intensified when her younger sister Hermina died in 1880. Hilma was 18, her sister 10. Her spirituality is undoubtedly one of the most fundamental aspects of her personality when trying to paint a picture of the real Hilma af Klint. Together with four likeminded women who shared her interest in the paranormal – Anna Cassel, Cornelia Cederberg, Sigrid Hedman and Mathilda Nilsson – “The Five”, as they came to be known, was formed, spurred on by the quest for spiritual enlightenment.

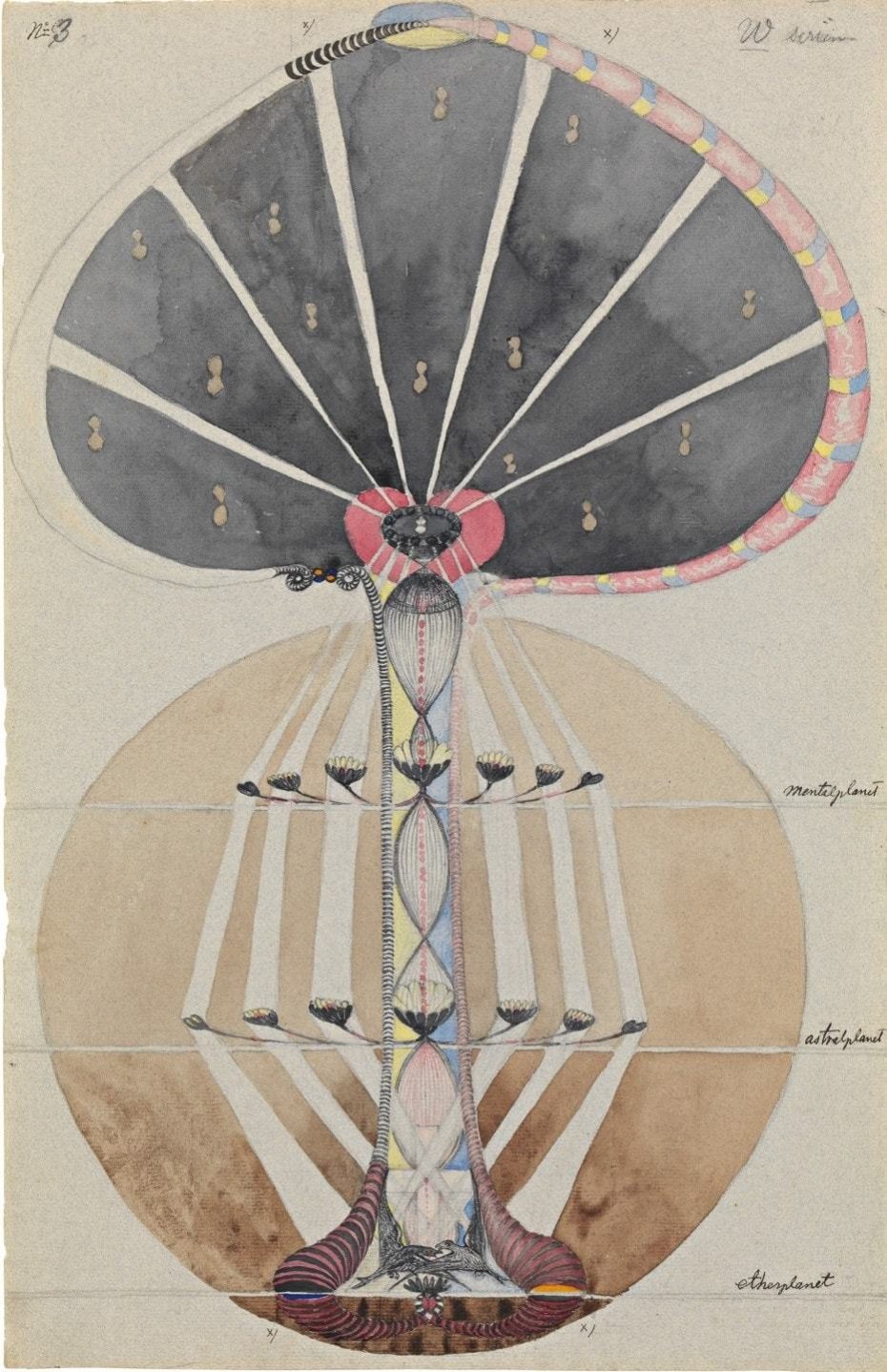

Hilma af Klint was not only De Fem’s founder but also their medium. The women keenly explored the mystic, paranormal and spiritual through regular séance meetings. Meetings were opened with a prayer, then meditation, next the Christian word and finished with a séance. They believed they were receiving messages at the séance from the The High Masters (‘Höga Mästare’). Allegedly, in 1904, prompted by an entity from the universe called Amaliel, Hilma af Klint was instructed to paint ’the immortal aspects of man’ on ‘an astral plane.’

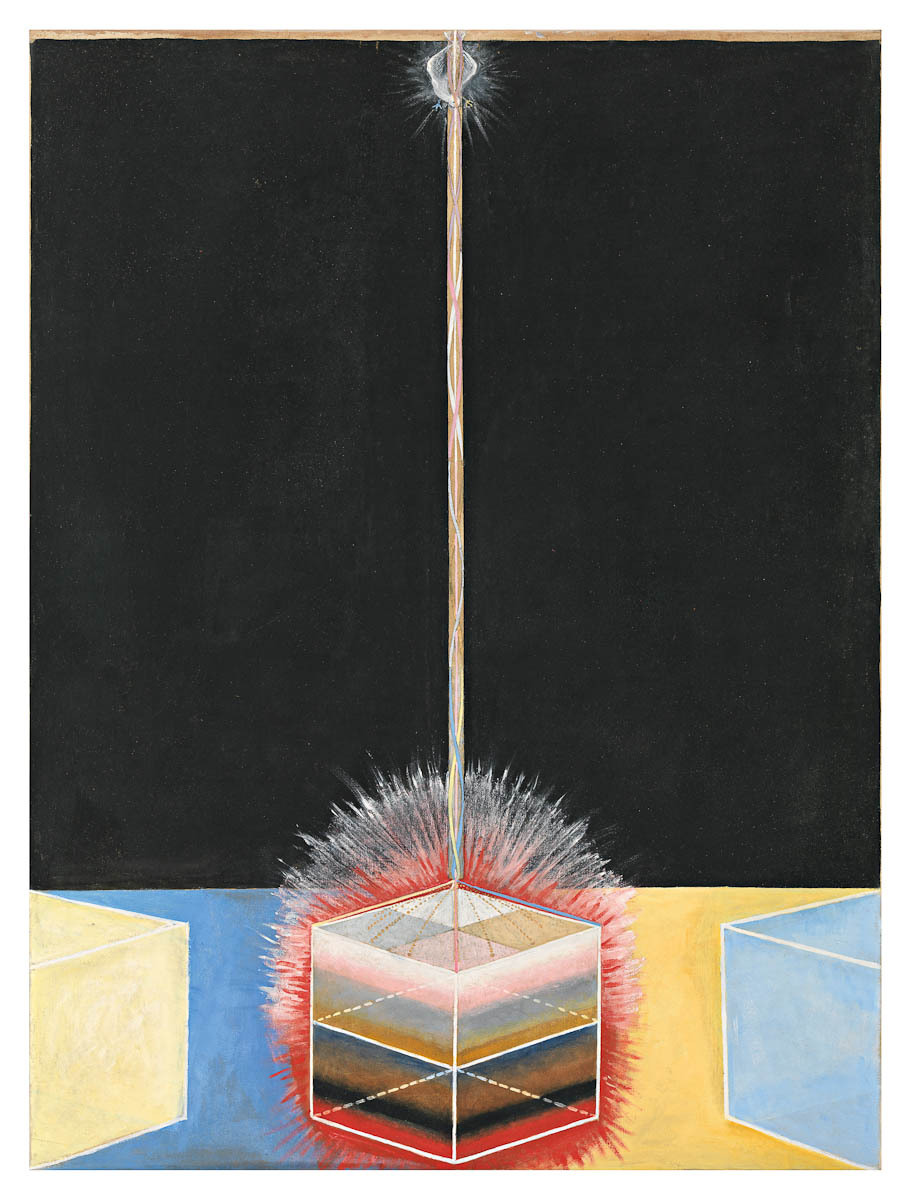

Hilma af Klint claimed that she was merely a medium and that the Higher Masters would direct her to create these works for ‘The Temple’, a vague construct for a place to communicate her arts and sciences to the world. She wrote furiously – thousands of pages of notes were accumulated – and in one of these she wrote, “The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke”. It was at the age of 44, in 1906, that Hilma af Klint produced her first body of abstract works.

In 1908 a pivotal meeting transpired between Hilma af Klint and the influential Austrian philosopher, esotericist and founder of the Athroposocial Society, Rudolf Steiner. Hilma af Klint and Rudolf Steiner had a number of subsequent meet-ups over the next two decades and Steiner’s theories on the basis of a true knowledge of the spiritual world, would have a profound impact on Hilma af Klint’s later work. In 1908 she let Steiner see her 111 works in the Paintings for the Temple series, but he rejected them, declaring them not fit for Theosophy on the basis that black magic and occultism were frowned upon, and that it would supposedly take her contemporaries fifty years to decipher them. She was distraught by this criticism and stopped painting for four years.

Hilma af Klint gave Steiner photographs, some even hand-coloured renditions of her work. Steiner met Kandinsky shortly thereafter and one can’t help but wonder whether Kandinsky, who personally claimed to have created the first abstract painting in history in 1911, may have seen these photographs and that perhaps, inadvertently, his own abstract art direction may have been shaped by these. Lore has it that Hilma af Klint deliberately chose not to show her abstract works while she was still alive, but there’s some evidence that she had in fact discussed the possibility with Peggy Kloppers-Molzer, a member of the Anthroposophical Society. Nothing came of the talks, but a few years later, in 1928, she did exhibit some of her large paintings in London at the World Conference on Spiritual Science. Perhaps, true to Steiner’s opinion, the world may indeed not have been ready for Hilma af Klint’s view.

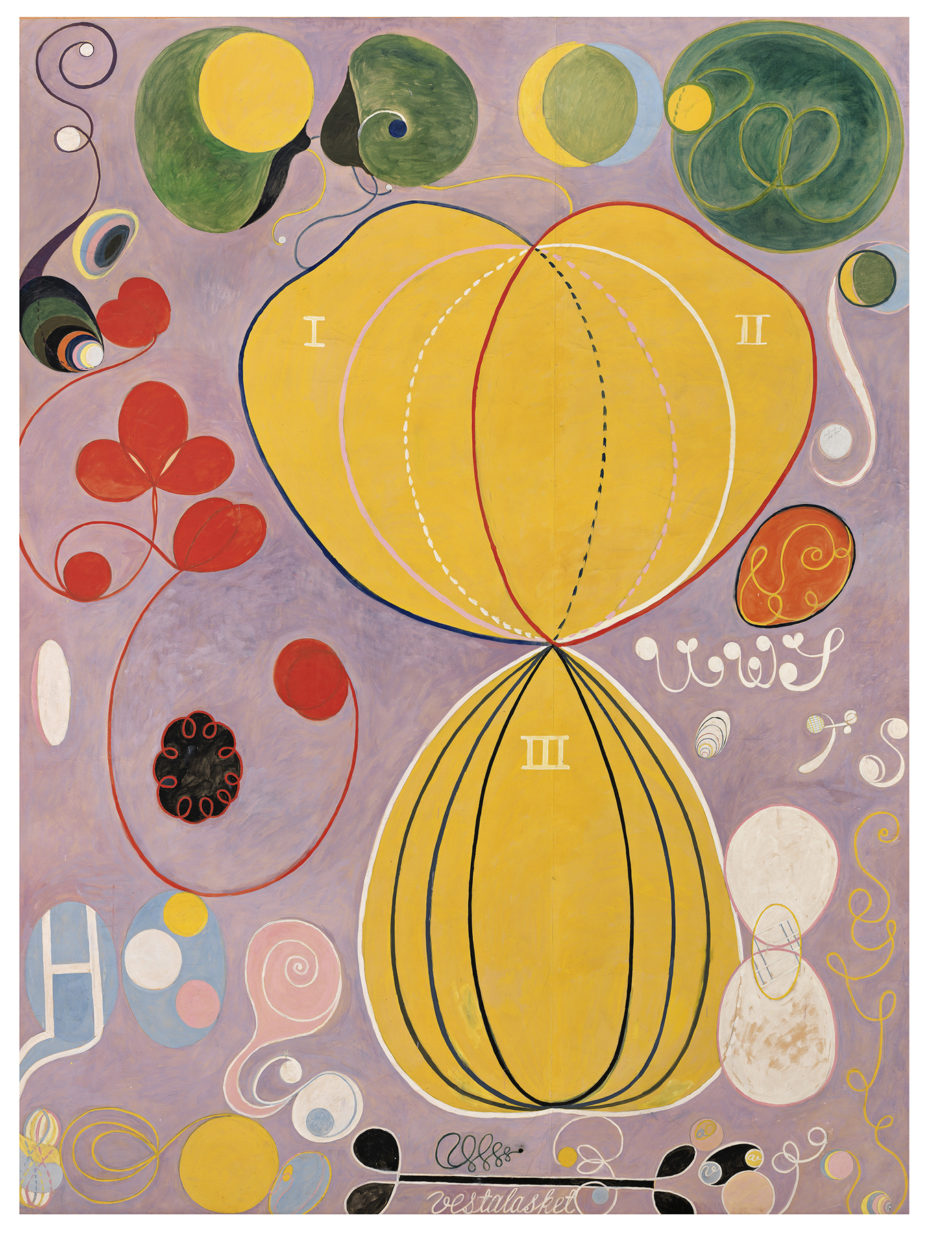

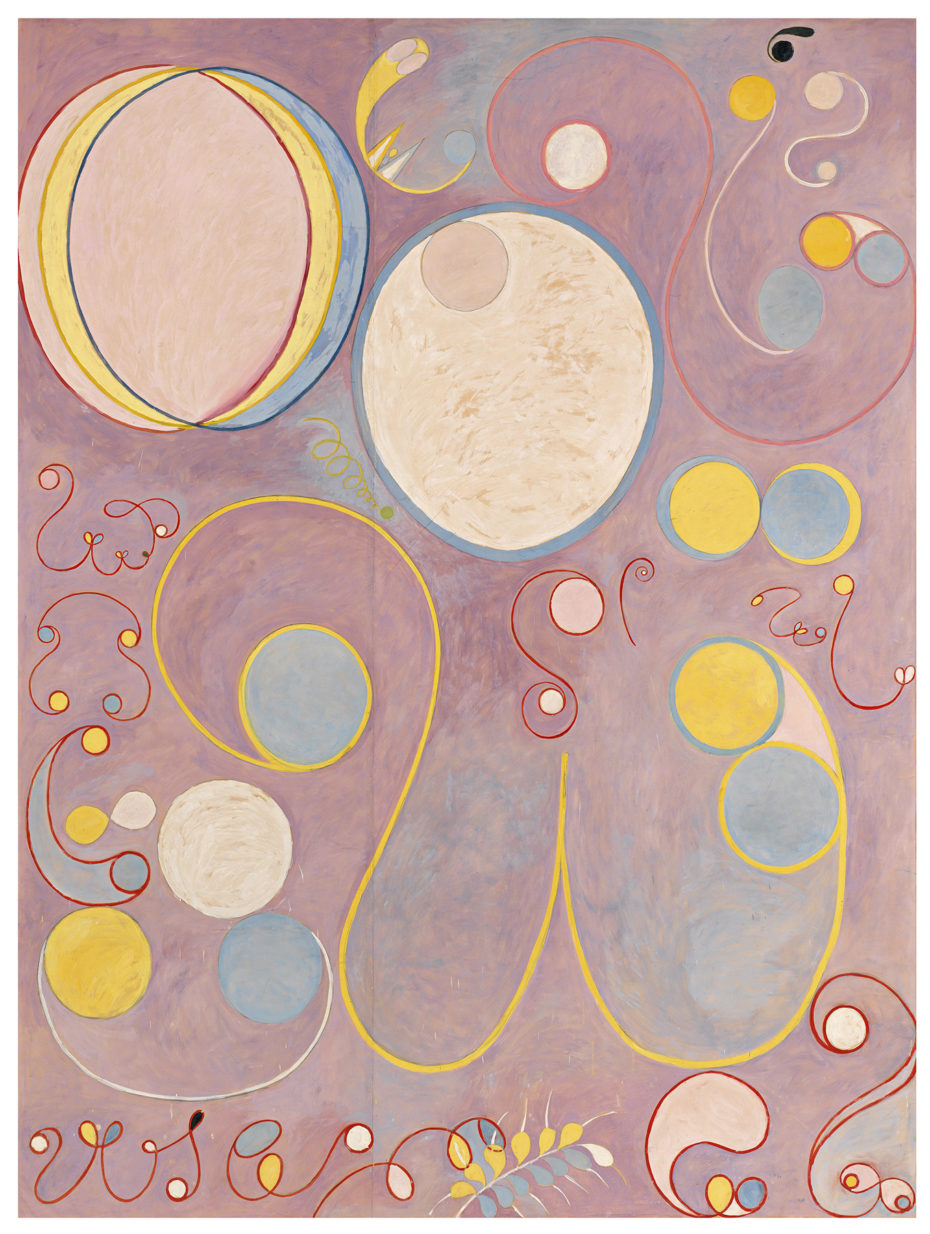

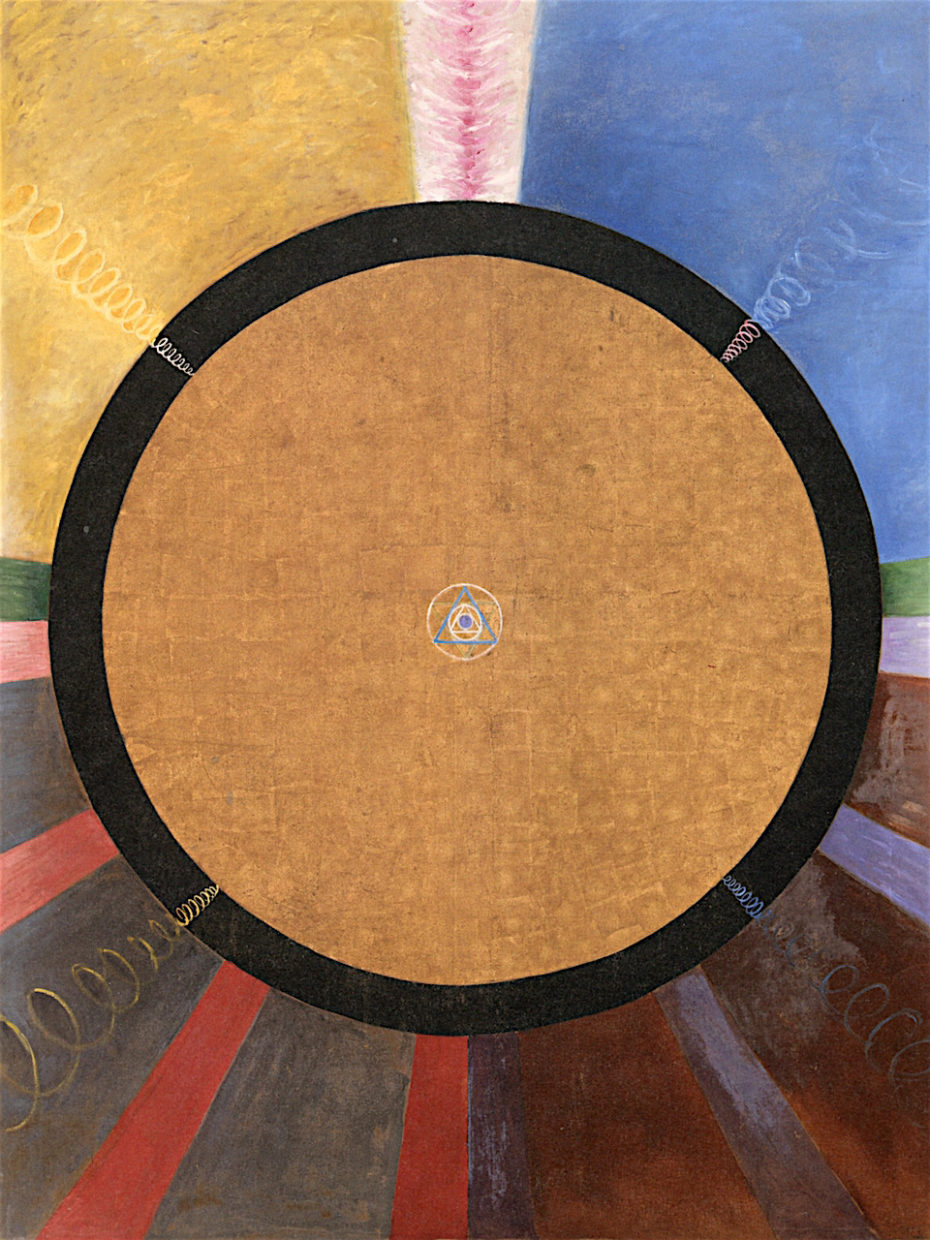

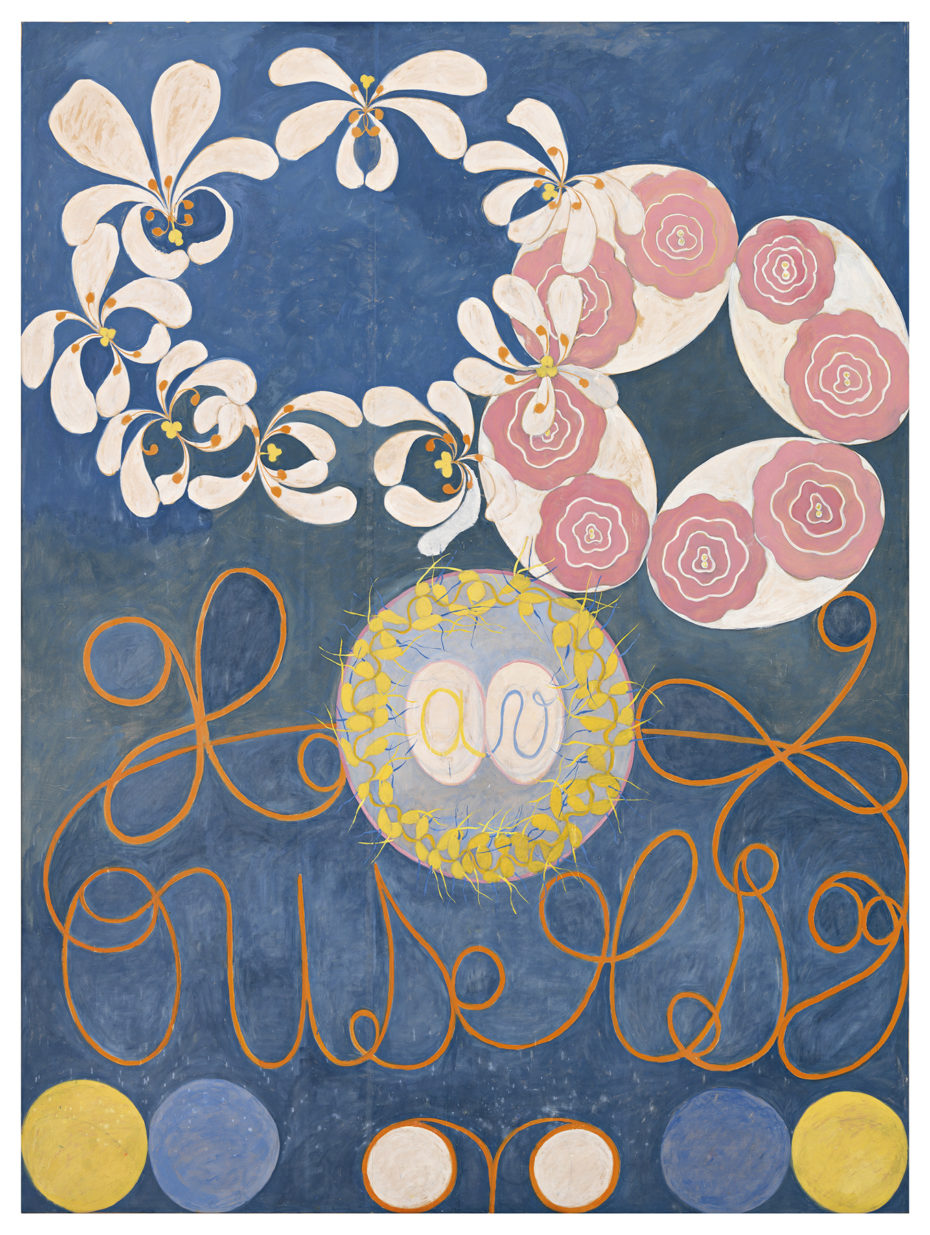

To look in a little more detail at the incredible body of work Hilma af Klint left behind, between 1906 and 1915, almost 200 works in the series Paintings for the Temple were created, entirely spurred on by Spiritism. The Ten Largest, a progression of wall panels are the key works, mostly painted in oil and tempera, describing life from childhood to old age. They are monumental – over ten feet tall, especially when considering the petite (5 foot) stature of the painter.

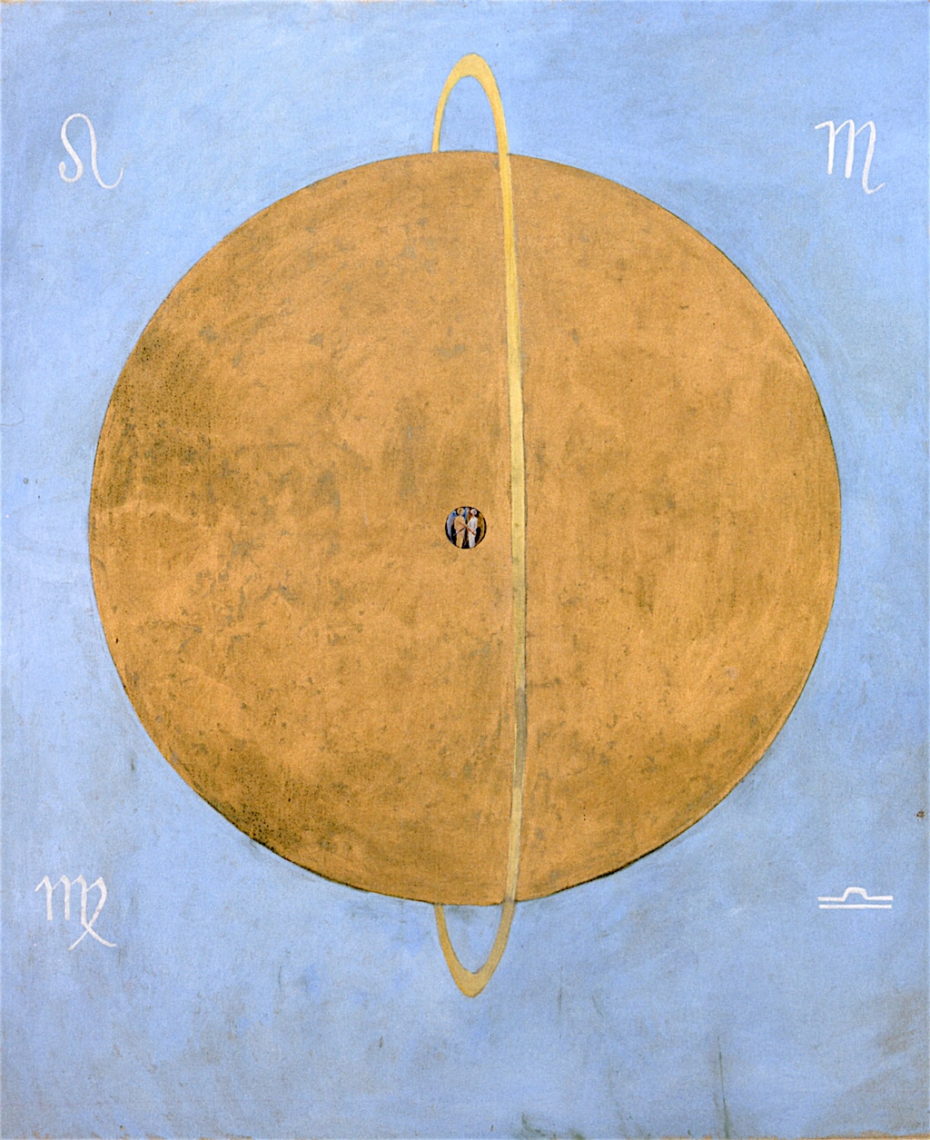

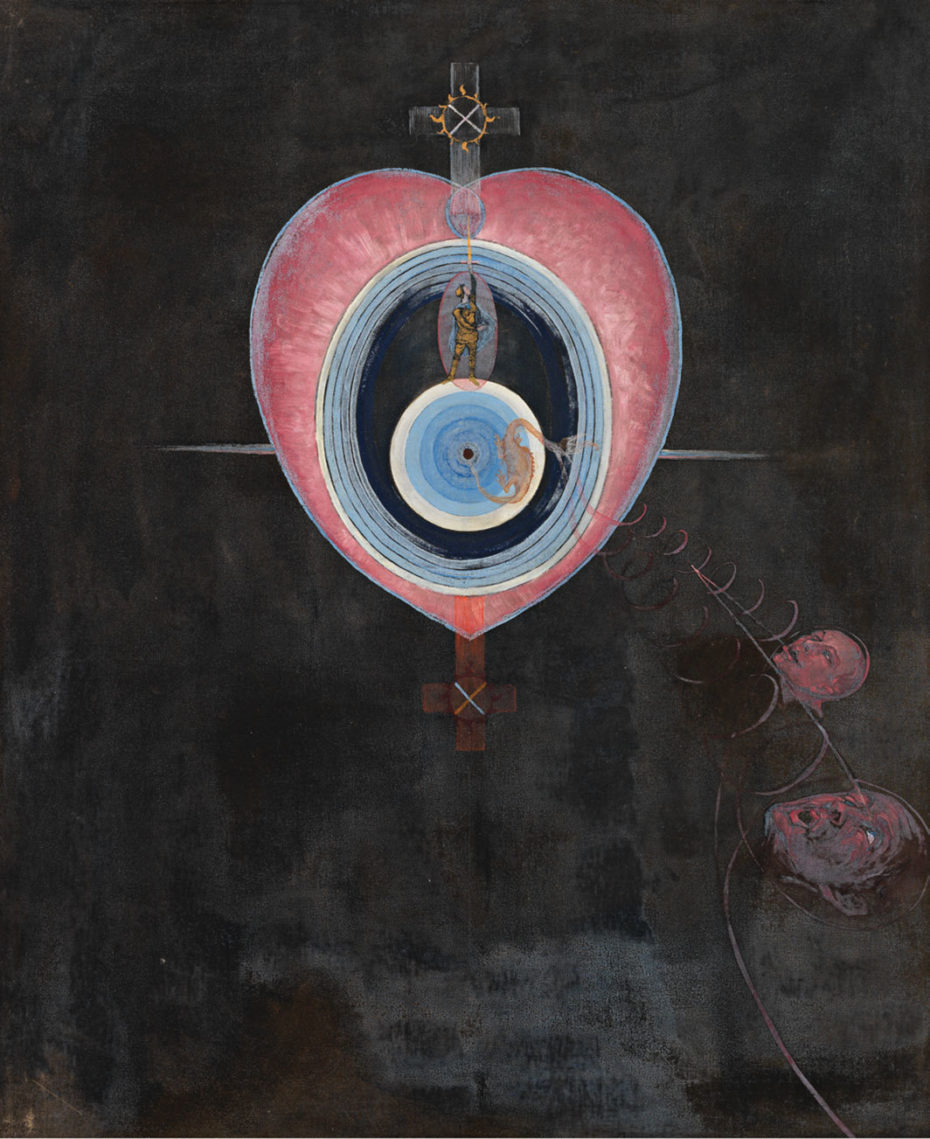

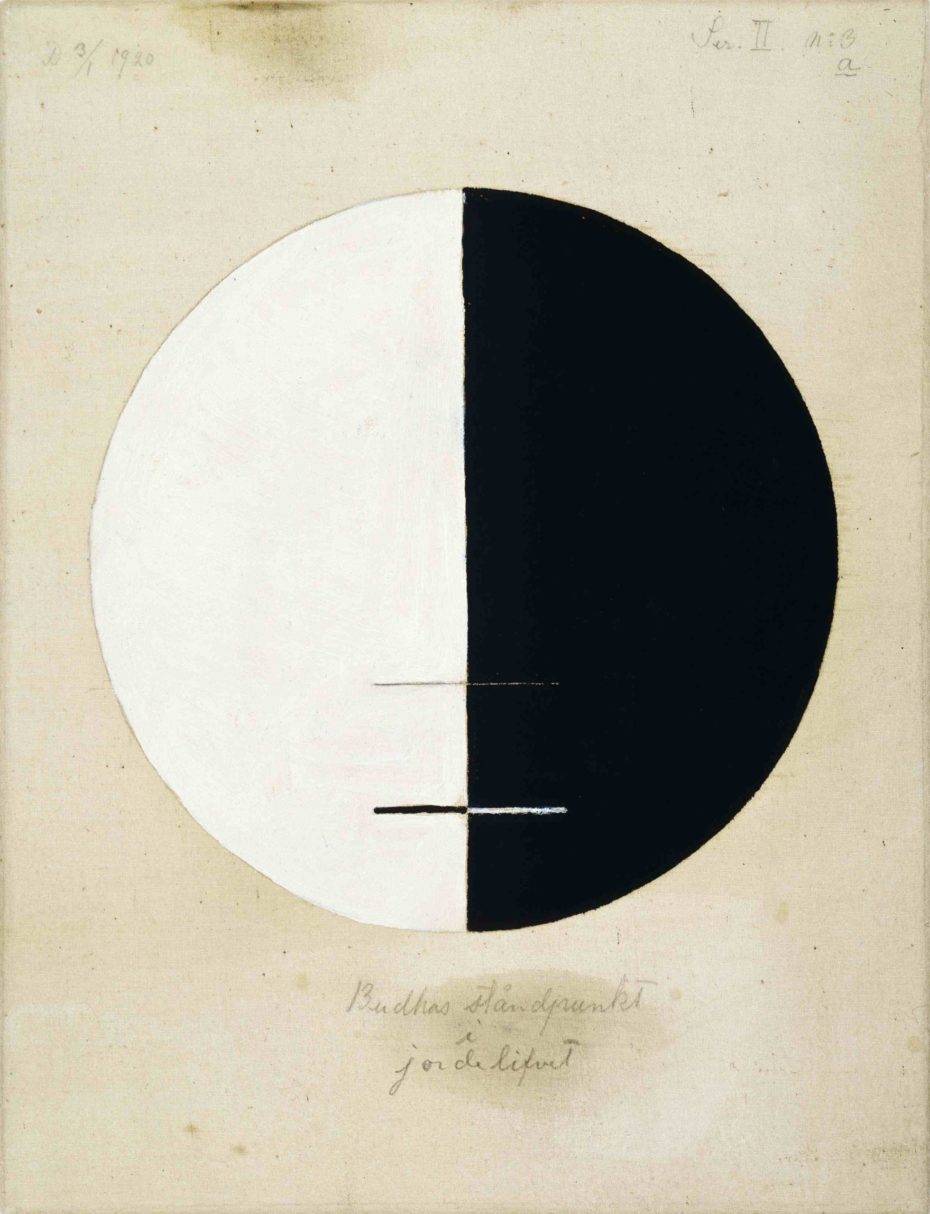

These works are psychedelic and verge on pop-art, they’re full of recurring iconography and squiggly lines, inverted commas, unravelling threads, organic shapes (like the spiral pattern of a curvy snail’s shell) and geometric symbols – squares, triangles, circles, which are often symmetrical, segmented and painted in juxtaposing shades. Using her own iconography, in the world of Hilma af Klint, spirals may have symbolised evolution. ‘U’ we think is the spiritual world, the overlapping disks is unity, and roses, masculinity. It is speculated that Goethe’s Theory of Colours (1810) (in which green for example, symbolises complete harmony) may have been an influence. She relished in exploring dualities and juxtapositions – male and female sexuality, for example. Two of the works The Swan and The Dove are metaphors for transcendence and love respectively.

Hilma af Klint’s work is both universal and esoteric. She fostered unorthodox associations with colour: yellow represents the male spirit whereas blue is that of the female spirit, pink, a colour she adored and red, stands for love – both physical and spiritual. Her use of colour is inspired, endearing and subtle: duck-egg blue, salmon pink, dusty rose, peach and primal red are in such eye-pleasing harmony on her canvases, it’s as if orchestrated by a higher hand.

After the Paintings for the Temple were completed, she claimed that the spiritual guidance ended. She now used water colour and kept building up a body of abstract works – albeit much smaller pieces. Subject matter would vary from religion to the duality of the physical and esoteric. Two water colours painted in the 1930s, The Blitz and The Fight in the Mediterranean, are eerie premonitions of WW2.

As for interpreting these works, their almost Jungian spatial and primordial geometry can be analysed on multiple levels, should one want to approach them from an intellectual angle. Or you could just allow them to speak to you at a human level – and they will. An inexplicable response to these works is the visceral way they touch audiences across all cultures and ages – from high-brow art critics to the ordinary person in the street, from old to young. It’s as if these works offer us a portal into our own subconscious as well as the into mysteries of nature, a kind of an Alice in Wonderland rabbit hole, a climbing into the wardrobe of the Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe. And this, no doubt, is exactly the way Hilma af Klint intended them to be: thought-provoking, visceral, powerful, more than just eye candy.

Hilma af Klint never married. She worked in splendid isolation most of her life and died penniless on October 21st, 1944. She was almost 82 years old. Although the world hadn’t seen most of her work, she was remarkably confident, especially for a penniless artist, that her trailblazing legacy would leave an immeasurable mark on the world. She also understood that the world at the time wasn’t ready to take on board her revolutionary ideas – both in painting and in written form – and she stipulated that her work was to be kept under wraps until twenty years after her death. She destroyed all her personal correspondence and bequeathed her entire collection of over 1200 paintings, 100 texts, 26 000 pages of notes and 125 diaries to Erik af Klint, her nephew. She was buried in a naval graveyard at Galärvarvskyrkogården at her father’s plot, with no mention of her own presence on the gravestone.

The crates containing all her treasure were opened at the end of the 1960s. The Moderna Museet in Stockholm was offered a donation of her work in 1970 but they declined, apparently because she was not considered a recognised modernist. Erik af Kint then donated her body of work (over 1200 paintings) to the Hilma af Klint Foundation, from where it reached a global audience. It was the 1986 Los Angeles show The Spiritual in Art that properly first exposed this unseen visionary talent to the world. But when MoMA’s influential 2012 show Inventing Abstraction: 1910-1925, notably left out Hilma af Klint, their explanation for their decision to exclude her from the genre was her links with occultism. It was befittingly at Stockholm’s Pioneer of Abstraction show in 2013 – the most popular exhibition in the history of the museum – that Hilma af Kint finally exploded onto the international scene. A subsequent exhibition of her work at the Serpentine Galleries, London in 2016 was ultimately well received.

Her work has since been exhibited far and wide, in prominent galleries like the Guggenheim in the New York and in galleries in Australia, New Zealand, The Netherlands, Germany, Norway, Israel and Italy. There is a dedicated room at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm where Hilma af Klint’s work is shown continually. Hilma af Klimt was a visionary painter, spiritually in tune with the world around her and uncannily open-minded for her day. Although branded as having dabbled in the occult, she was a humanist obsessed with understanding the code of science, nature and life and tried to convey this through her works. She still stands outside the door of establishment acceptability, awaiting her long overdue call to enter.