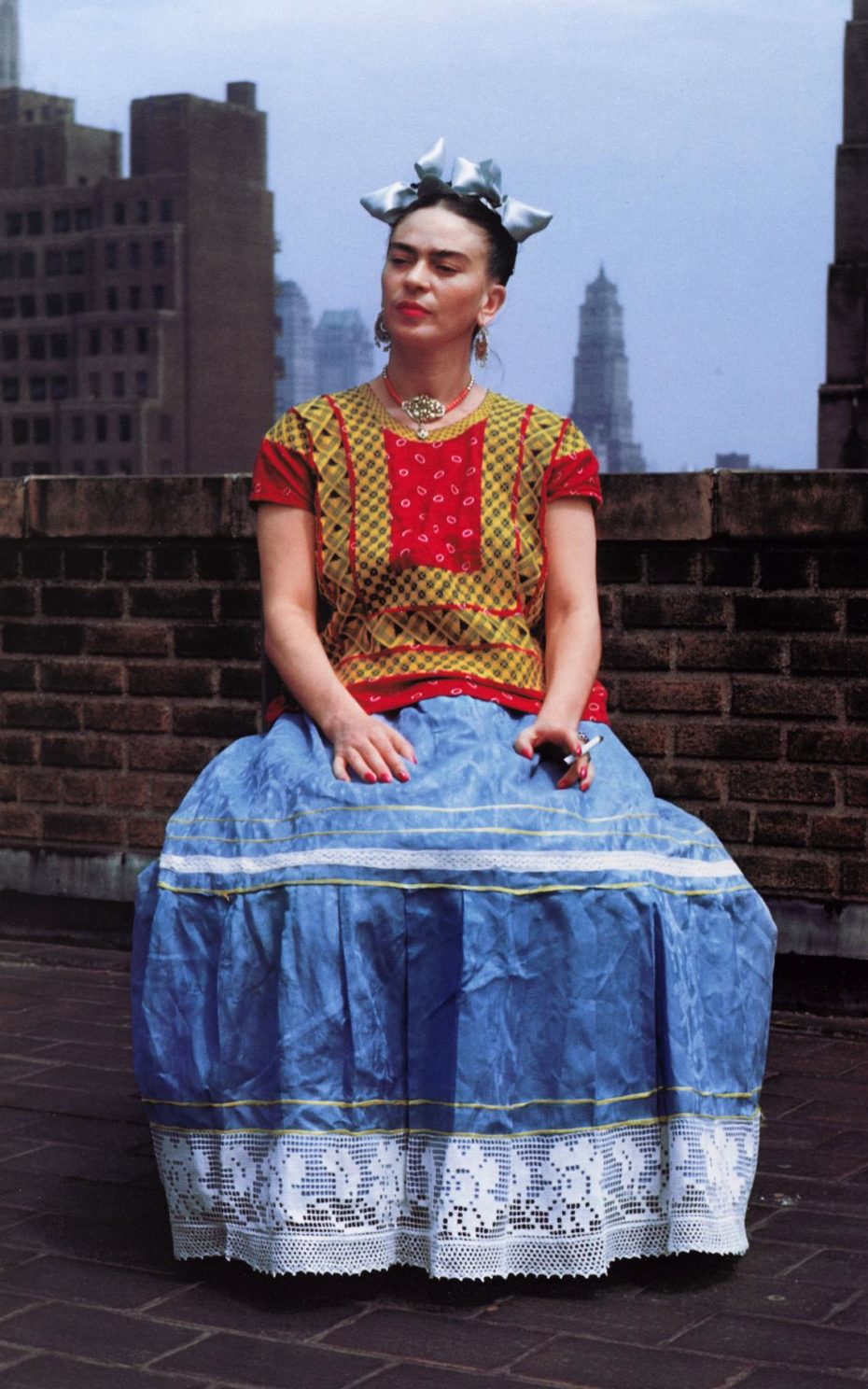

That unapologetic unibrow, the halo-crown of jet-black centre-parted flower-adorned plaits, rouged cheekbones and russet lips frame a fearless stare. Her Mexican torzal necklaces, silver filigree earrings and onyx beads you and I could only hope to collect over a lifetime of scouring obscure artisanal markets. No prizes for guessing who she is. But let’s drag ourselves away momentarily from the artist and icon that is Frida Kahlo and turn our attention to the extraordinary Zapotec tribe that was instrumental in her making.

Let’s go way back to the Aztecs, Mayans and Zapotecs of South America who built vast cities of pyramids and palaces, rich with elaborate architectural and decorative pattern work. Stretching across what is now Mexico, this was a world apart from western knowledge until the fateful arrival of the Spanish conquistadors at the end of the 15th century. ‘Mesoamerica’, the twisting ribbon of land between North and South America, was a diverse and thriving cultural hub at the time of the arrival of Christopher Columbus. The central part (what is now Mexico) was fertile and lush, supporting the Aztecs to the west, the Mayans on the Yucatan Peninsula to the north and the Zapotecs to the south. They constituted a loose confederation of city states whose power and influence upon each other had come and gone, waxed and waned over the centuries. The ruins they left are encrusted with decorative religious and cultural carvings: icons, hieroglyphs and complex decorative geometrical patterns. Described as ‘pre-Colombian’ (a rather colonialist reference) these societies were agricultural, militaristic and advocated a definitive calendar that predicted the end of the world.

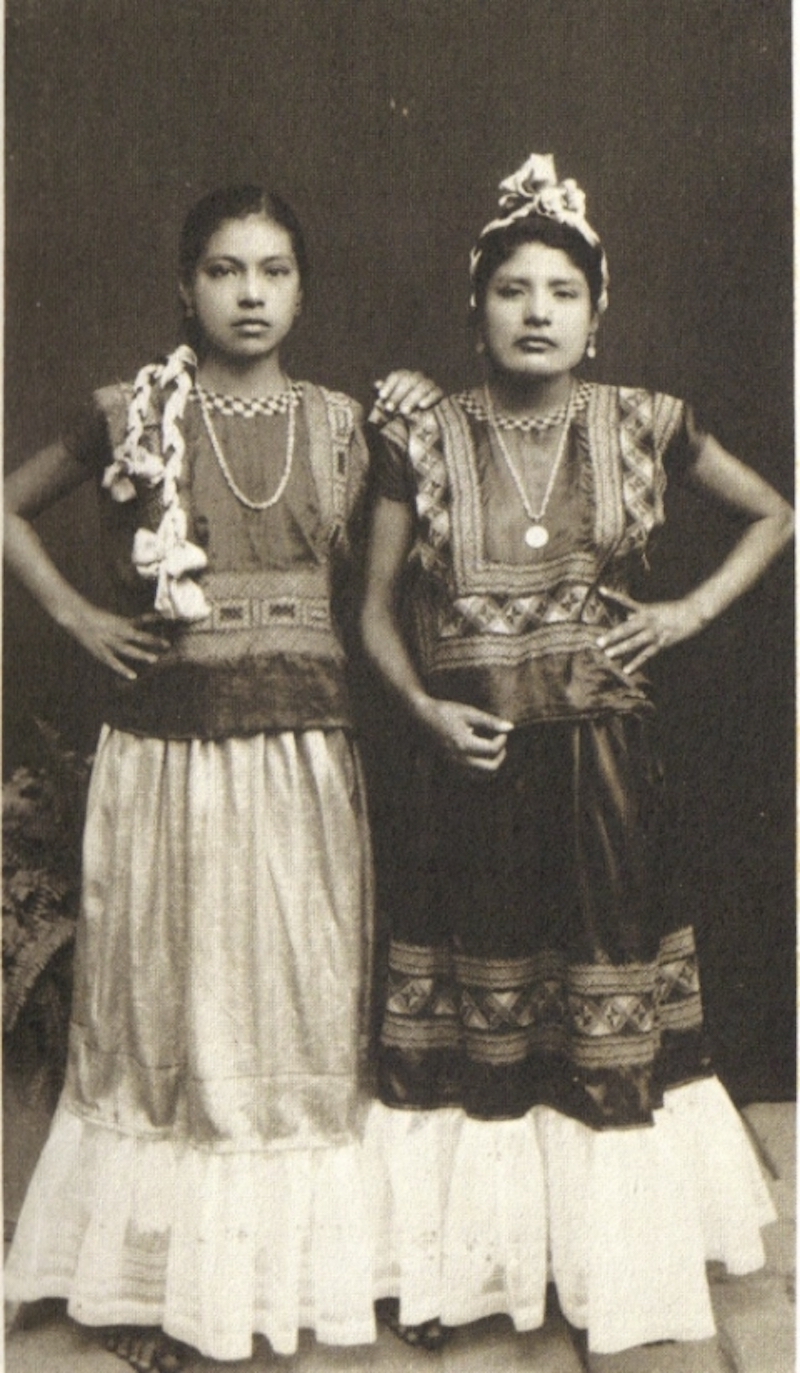

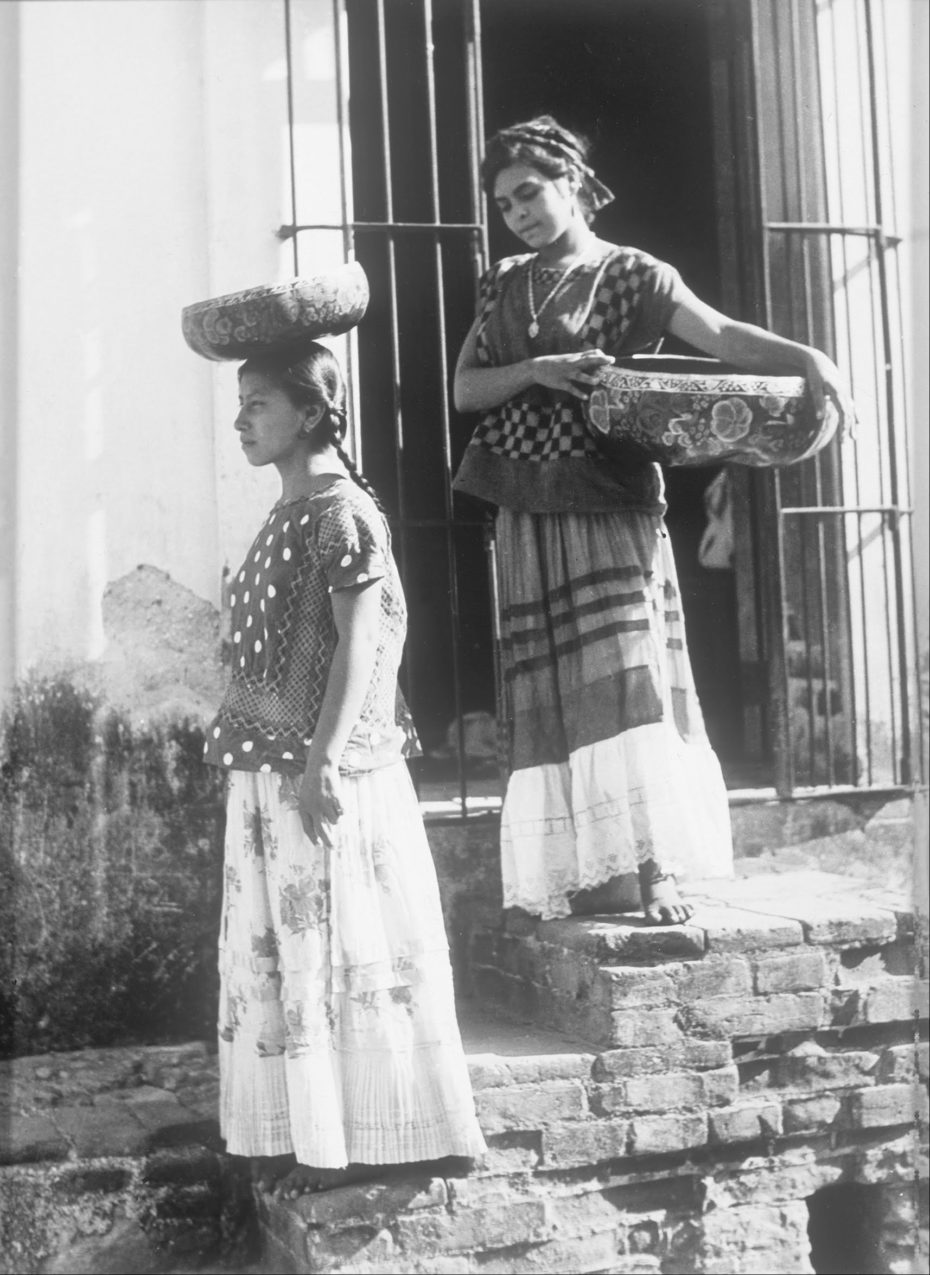

In the 1930s, Frida Kahlo came to see the Zapotecs and Aztecs as wholesome and earthy cultures, living in harmony with nature. The Zapotecs traded and worked shells, sponges, gold, amber, salt, feathers, furs cotton, spices, honey, cocoa and other naturally occurring materials that were readily available from their immediate environment. They were the most productive goldsmiths in the region, a complex and organised trading society expressing itself through distinctive art and decoration, from clothing to architecture. The stylings of these ancient artefacts survived the test of time and were transferred to other mediums such as textiles and fashion design – the boxy blouses with their distinctive bordered panels Frida so adored, being a good example of this.

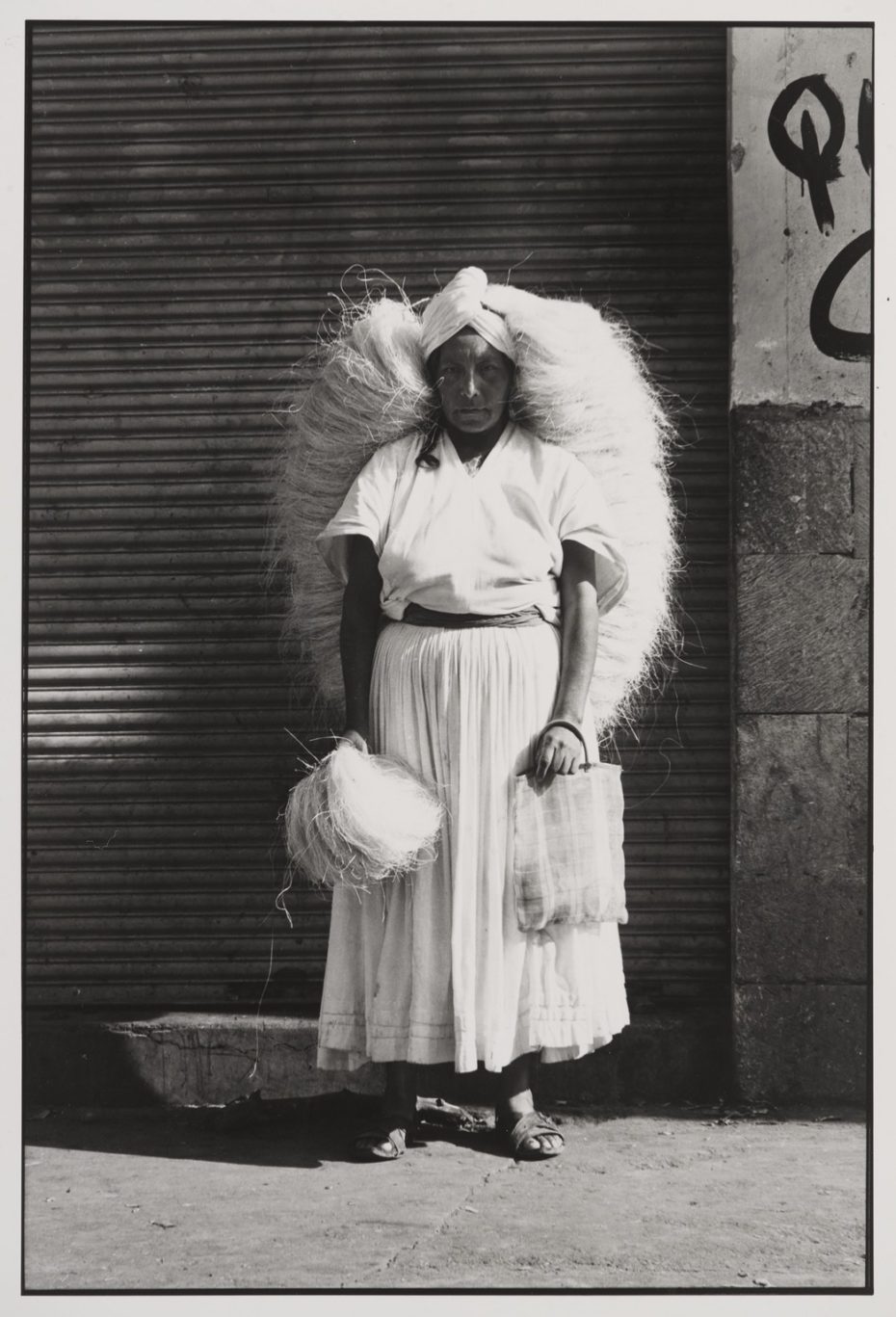

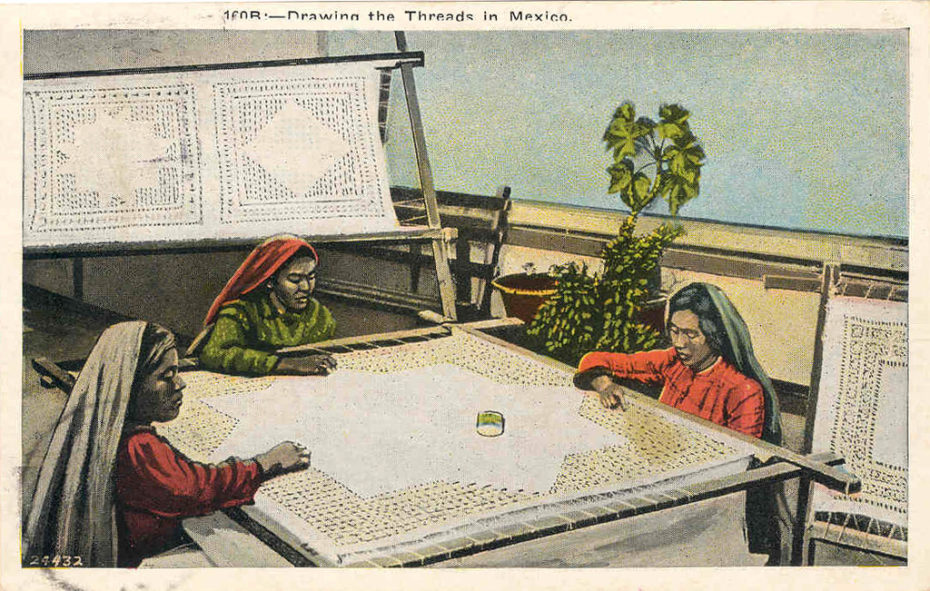

In the south of Mexico, in what is now Oaxaca State, the ancient weaving traditions are still practiced, notably the incorporation of ancient symbols and patterns woven by particular families of weavers. Every family produces their own unique combinations of the design and whist there may be some repetition in shape and pattern, by using a distinctive set of colours each family’s output is special. The symbols are not invented, but are a continuation of the Zapotec culture, still carrying their deep spiritual meanings, honouring nature and their gods.

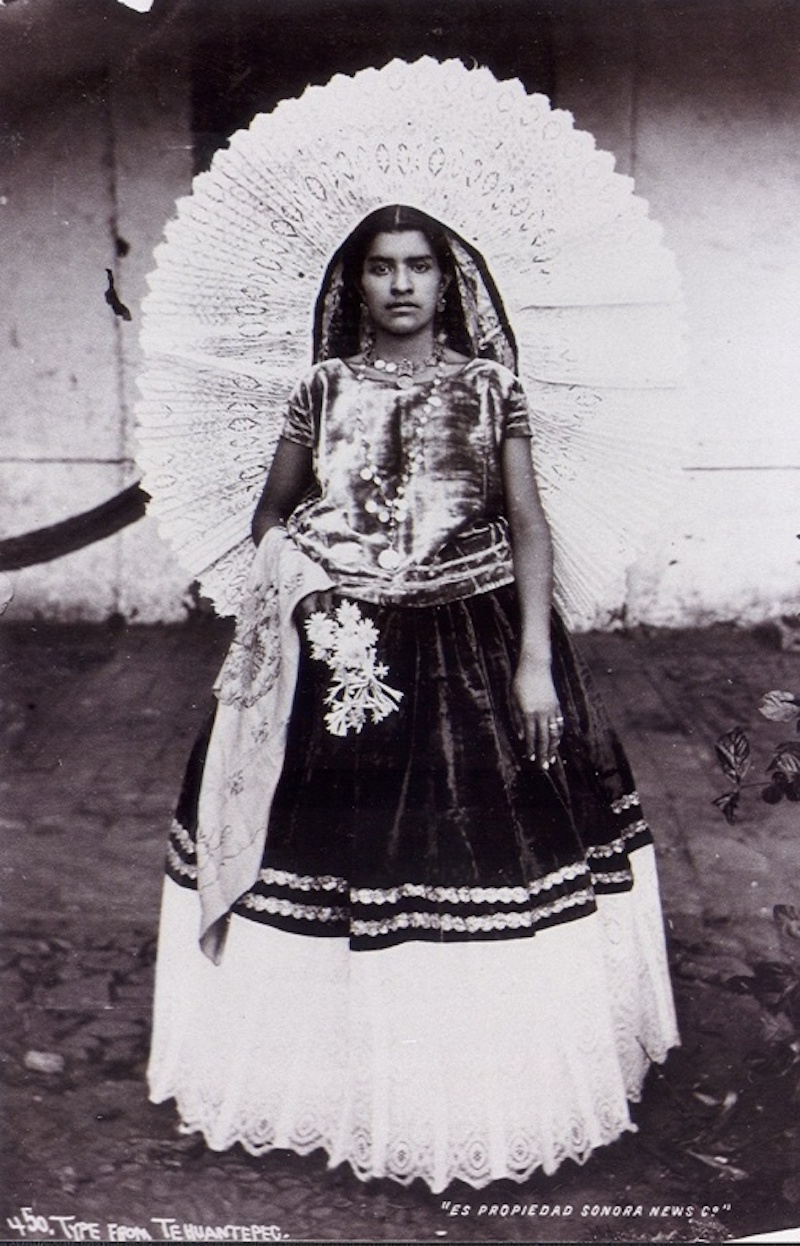

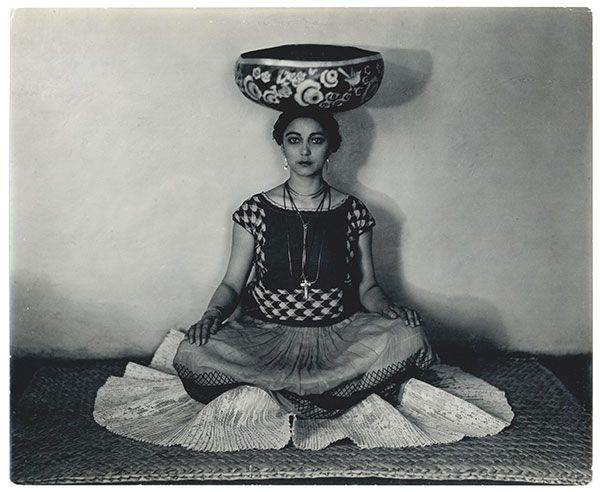

Their capital, Tehuantepec, is a city now famous for its distinctive style of dress amongst women; traditional full skirts, artisanal embroidered blouses and florid hairstyles. It’s a visible reminder that in this region, the Tehuana women rule the roost in their historically matriarchal society where women once had exclusive trading rights and dominated the in-town markets. Incidentally, until the 1970s there was a complete ban on men at the markets, but the rule has somewhat relaxed since. To this day it’s still estimated that men make up less than five percent of the total population at the markets, because traditionally, they were out working in the fields and women were left to make the calls inside, and outside, the house. The business acumen of the women of Tehuantepec was widely celebrated in 19th century writings, which no doubt must have appealed to an emancipated Frida Kalho almost as much as their aesthetic.

What will have made it even more appealing to Frida was that the Zapotecs were a liberal society by modern standards. From earliest pre-Hispanic times to the present day in Oaxaca, they have acknowledged and tolerated three genders: female, male and muxe, a term unique to the Zapotec to describe a person who was born a man but who dresses and behaves in ways otherwise associated with women. Traditionally considered good luck, muxes are not referred to as “homosexuals” but rather seen as a third separate gender, without the same pressures to “pass” often faced by transgender people in Western societies.

Anthropologist Beverly Chiñas explains that in the Zapotec culture, “the idea of choosing gender or of sexual orientation is as ludicrous as suggesting that one can choose one’s skin color.” (Learn more about the complexities of muxes here).

Frida Kahlo’s own views on gender identity and her personal conduct also sat well with this tradition. Like the ancients, she accepted gender fluidity, she herself felt both male and female – the shadow of a moustache deliberately accompanied the famous unibrow in her paintings affirmed that. She was photographed numerous times as a young woman sporting a man’s suit with swept back hair and puffing on a cigar.

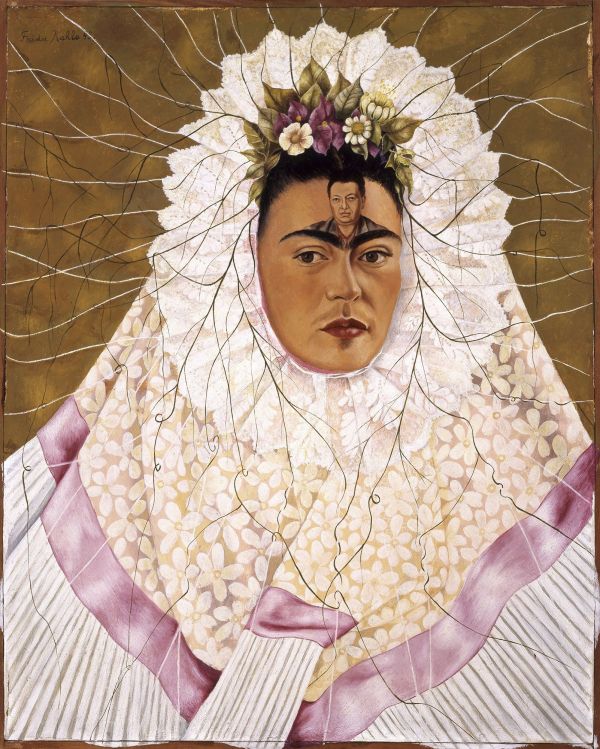

While Frida’s father was a white German-Hungarian photographer, Kahlo’s mother was ‘mestizo’, half-Spanish, half-indigenous Tehuana, the descendants of the Tehuantepec, Zapotec women. From a young age however, Frida was protected by her privileged class, sheltered by her bourgeoisie background, and did not share the same realities of the Tehuana women living in poverty-stricken communities where indigenous people were, and still are, actively oppressed in the aftermath of colonisation. If her 1939 painting, The Two Fridas, is anything to go by, Kahlo later became quite aware of her freedom to straddle both cultures thanks to her social class. On the left, she paints a more of a European Frida, dressed in a white Victorian lace dress, while the figure on the right represents a in a Mexican costume, the person that her Diego Rivera championed and ultimately preferred.

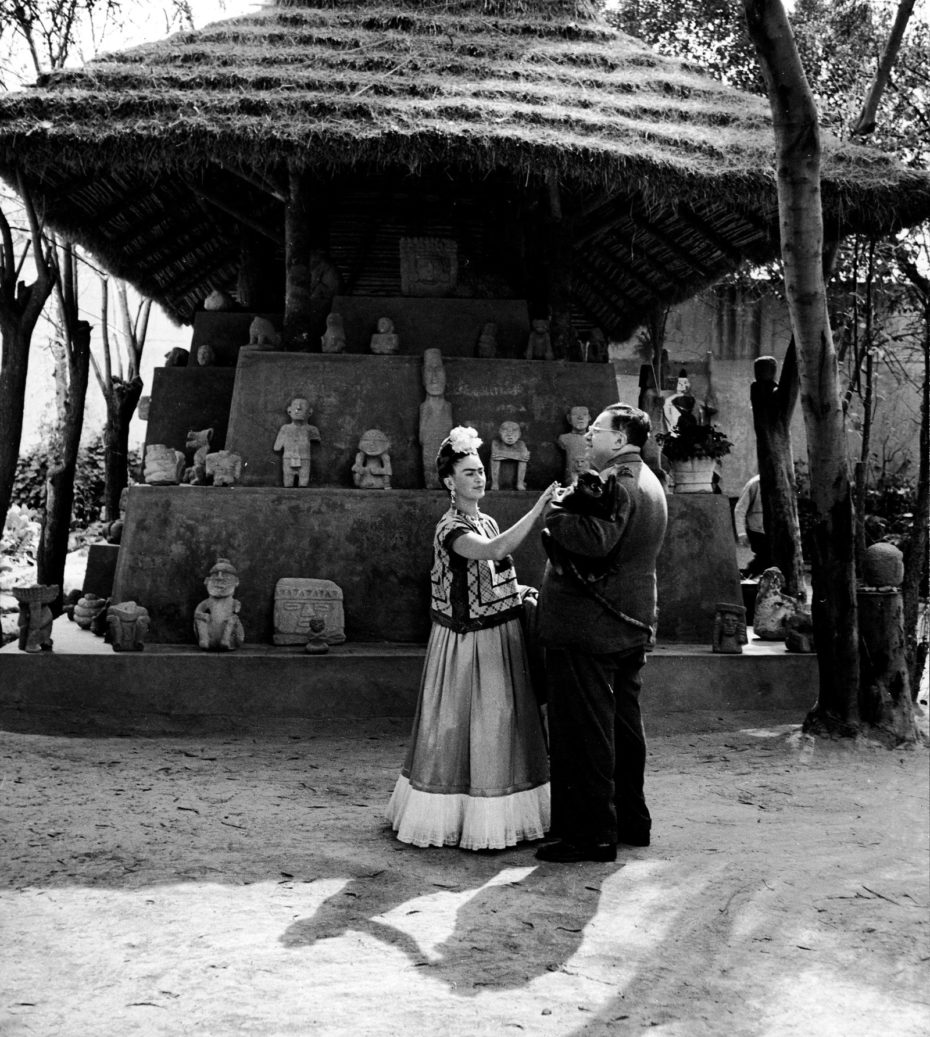

Frida met Diego Rivera the great muralist, womaniser and close friend of Leon Trotsky’s, through her membership of the Communist Party. Their relationship was a passionate and turbulent one. She married him in 1929 and divorced him, just to marry him again in 1940. A fellow comrade, Rivera created numerous political murals that attacked the ruling class, capitalism and western materialism and in doing so elevated and romanticised Mexico’s native heritage and anti-colonial stance. It was Rivera that suggested Frida Kahlo should wear the traditional garb as a show of Mexican pride. Frida needed no convincing and she embraced the idea wholeheartedly.

The previous decade’s revolution had looked to forge a new and integrated nation of all ethnic descents and key to this new identity was the use of indigenous art and icons: the works of the Aztecs, Mayans and Zapotec cultures that had flourished before their destruction by the Spanish (whose European-based culture had been the country’s historic image to that point) were actively encouraged. The new Ministry of Education went out of their way to promote the adoption and use of indigenous art as an escape from Mexico’s damaged past.

For Kahlo and Rivera, celebrating Mexican indigenous culture was an act of political solidarity to show what old and new Mexico were about: a society of equals, a society of the land and all sharing a common heritage and mutual goals. The new republic offered Frida Kahlo many blank canvasses – new socialist agendas, new arts and a new cultural outlook, new roles for women and new like-minded comrades, all seeking to reinvent Mexican society. Fiercely political and proudly queer, her lust for life and lovers included Leon Trotsky, Georgia O’Keeffe and Josephine Baker. A childless Frida Kahlo devoted all her creative energy to this whirlwind of social change.

In Zapotec art and culture, Kahlo found the perfect vessel for her national and own self-expression. No doubt she would have been fascinated with the ancient weaving techniques of her mother’s Tehuantepec heritage, in which each pattern tells the story of the weaver.

Frida combined her modern frocks with Mayan Huipil blouses and paint herself wearing ceremonial headdresses known as the resplandor. She’d wear her colonial silver bangles with indigenous beads and necklaces, she’d drape rebozo scarves around her shoulders – first brought to the region by the Spanish during Christopher Columbus’ time and subsequently reworked by the Aztecs with traditional dyes and embroidery. Famously the rebozo was also worn by female revolutionaries in the 1910s to smuggle guns past government checkpoints. Wearing the symbolic rebozo scarf was Frida’s tribute to both pre-and post-colonial women alike, a nod to free-thinking inclusion and a manifestation of her own diverse social and political background.

Over the years she would purposefully mix Western fashions with traditional dress, using her eclectic wardrobe to express a feminist, political and nationalist Mexican identity, but also to navigate her experience of living in a disabled body. For example, the boxy-shaped embroidered Huipil blouses that she became famous for wearing, communicated a certain identity, but at the same time, allowed for her to discreetly hide the back braces and torso casts she was forced to wear most of her life.

Throughout her life she would apply this ingenious aesthetic to mastermind her self-image and art, and compensate for a disfigured, ailing body with smart accessorising – her long Tehuana skirts, colourful rebozo scarves and copious quantities of fabulous jewels served as beautiful and necessary distractions. She decorated her casts and braces with political jargon, she made and adorned her own lace-up, built-up boots by hand.

By the late 1930s, Frida’s artistic output was prolific, and after returning from her visits to America that helped crystallise her unique artistic persona, she was now recognised internationally. Appearances around in New York in her Zapotec dress caused a fashion sensation. André Breton, the French surrealist artist, would describe her art in 1938 as a “ribbon around a bomb”. In 1938 Elsa Schiapparelli designed ‘La Robe de Madame Rivera’, in response to Kahlo and her Tehuana ensembles with their transparent black sleeves and red floral beads.

Today her image stares at us from postcards, fridge magnets, calendars, diaries, Barbie dolls, snapchat filters, phone cases, jewellery and runway collections. She is the eternal muse to design houses like Roland Mouret, Jean-Paul Gaultier, Valentino and Etro. “Frida Kahlo” has become a global brand, her style a constantly returning trend at global fashion weeks. This is where, nearly 70 years after her death, questions of indigenous cultural appropriation are raised.

Frida is the archetypal female, the anthropomorphic woman that all genders can relate to, a symbol of female suffering – both socially and physically, but she’s also a victim of mass culture. The saturated pop culture phenomenon of “Fridamania” has caused her image to become literal and one-dimensional, and the indigenous iconography found in her artwork entirely lost in the process.

As we step back from the hype, let this be an opportunity to recognise the overlooked side of the story she was also trying to tell; an invitation to listen to and learn from the diverse communities that clearly have so much to share. As much as Frida and her iconic art empowers us to celebrate feminism, queer identity and find hope amidst despair, Kahlo’s legacy has the power to provide a fertile landscape for an overdue narrative that includes, honours and engages with the rich indigenous culture that inspired our complex heroine.