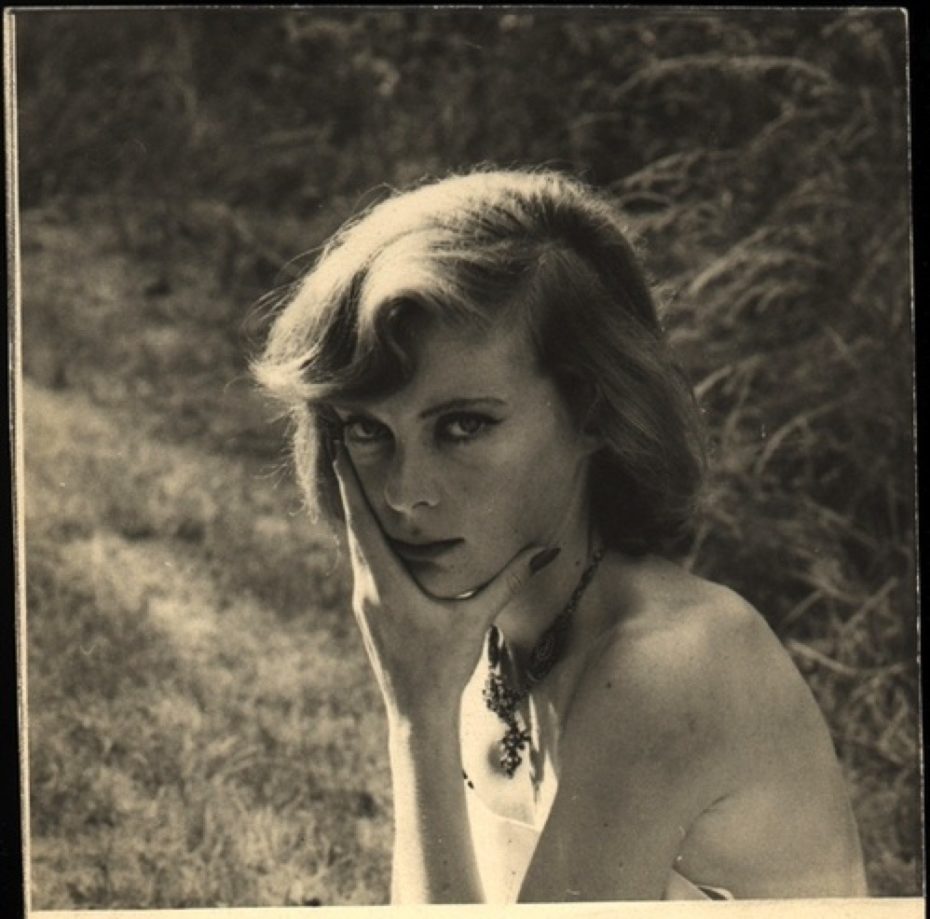

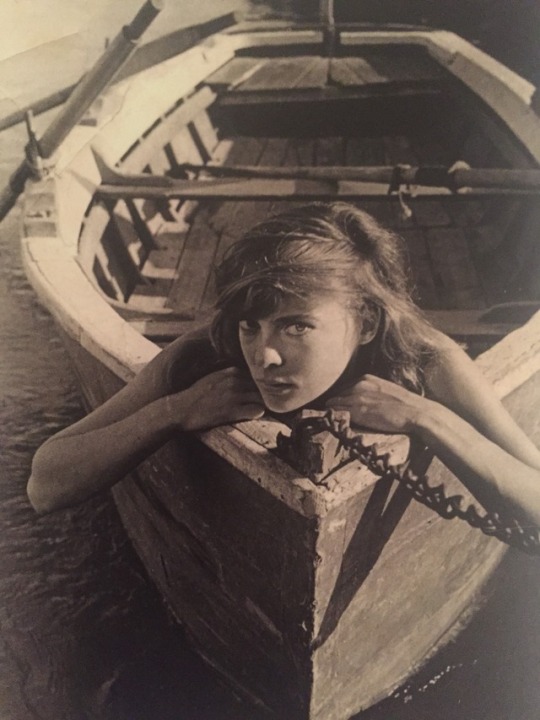

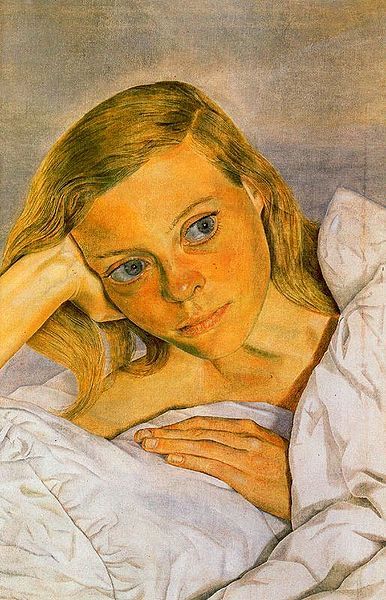

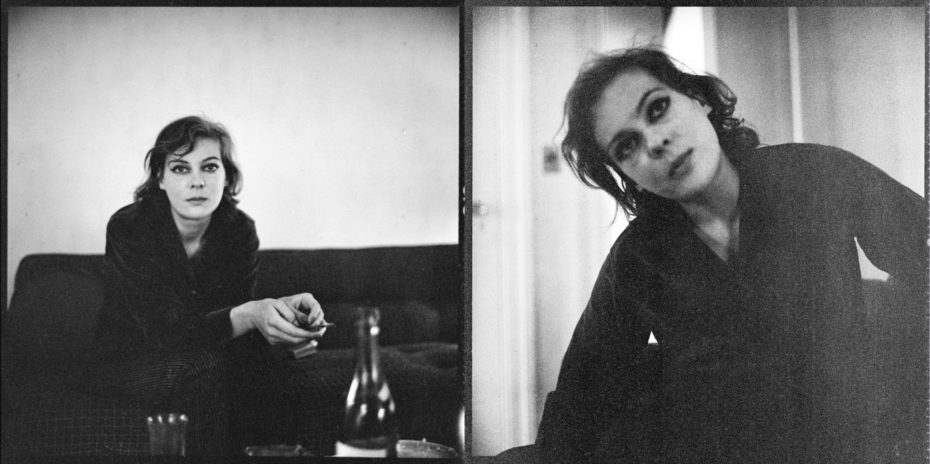

She was legendary, and she was a legendary drunk, though she claimed her family’s stout was undrinkable. Perhaps you know her as the heiress to the Guinness fortune, or for her high-profile marriages, first to the artist Lucian Freud, who painted her famous 1952 portrait, “Girl in Bed.” Her third husband, poet Robert Lowell, described her as “a mermaid who dines upon the bones of her winded lovers”. Lady Caroline Blackwood was not your average socialite. A macabre, witty, and original novelist, she broached very un-ladylike subjects such as suicide, rape and dished on the eccentricities and sufferings of her own aristocratic class. Her best characters were utter monsters and British critics noted the ‘brilliant irony’ and ‘rather brilliant bitchiness’ of her writing. Remembered as a great beauty and eccentric muse, we’d argue she’s better remembered as one of literature’s greatest and darkest writers of the 20th century. Oh, and someone call Hollywood, because her biopic is well overdue.

Born into the fabulously wealthy Guinness dynasty, Caroline Blackwood grew up among the aristocracy in her ancestral stone mansion in Northern Ireland. In 1949, she was presented as a debutante on London’s Park Lane before promptly beginning her rebellious campaign to defy and horrify her mother the Marchioness, by skipping college, finding mentors in left-wing journalists and falling in love with all the wrong suitors.

At a ball attended by several members of the royal family, the wife of Ian Fleming introduced her to the painter Lucian Freud. The night was seared into Caroline’s memory thanks to painter Francis Bacon, who sensationally booed Princess Margaret off the stage when she decided to take the microphone from the band and sing for the crowd in her notoriously off-key high-pitched voice.

Blackwood, Freud and Bacon became fast friends; a fashionable, artistic clique who drank in clubs like the Gargoyle and Colony. Emerging as the leading light of the bohemian arts scene and preferring the company of starving artists to the dukes and earls that courted her, she eloped with Freud to Paris in 1952, where they lived for two years and kept company with the likes of Pablo Picasso. As the story goes, Picasso once drew on her hands and nails and she refused to wash for several days.

The famous portrait, “Girl in Bed” was painted at the Hôtel La Louisiane in Saint Germain where all the famous jazz musicians from Miles Davis to Billie Holiday stayed, and where Sartre and Beauvoir lived for several years. At the time, the painting was received as a harsh iteration of Blackwood’s “great beauty”.

Perhaps he knew she was going to be the only woman to break his heart. His tendency for gambling and recklessness were among the reasons for the breakup of their marriage and she later wrote of their relationship: “I had dinner with [Francis Bacon] nearly every night for more or less the whole of my marriage to Lucian”. Following the break-up, Bacon revealed in letters that they feared Lucian would take his life.

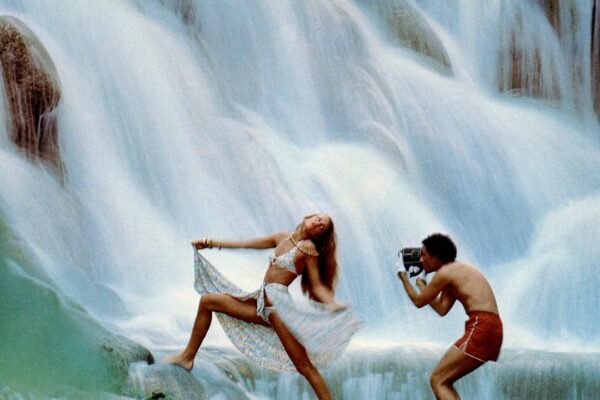

In the wake of their separation, Blackwood took an interest in acting and moved into Hollywood’s Chateau Marmont, while she played a small role in the television series, Have Gun Will Travel. In Los Angeles, she wrote an article about California beatniks, effectively launching her career as a writer. When she moved to New York, Caroline married composer and pianist Israel Citkowitz, a very accomplished man who was 22 years her senior. They were married for seven years, but by the time she gave birth to their third child, Ivana, their marriage was over too. It wasn’t revealed until Blackwood was on her deathbed that Ivana’s real father was in fact one of her rumoured boyfriends, screenwriter Ivan Moffat. Despite her infidelities, Blackwood stayed friends with her second husband, Citkowitz, even after she left him for the American poet Robert Lowell.

Blackwood’s obituary states that she then suffered a series of misfortunes, and that they all fuelled the flames of her career as a novelist. There was the death of her third husband, Lowell, who suffered the relentless cycles of bipolar disorder but ultimately died of a heart attack, and was found slumped over in the back of a NYC taxi cab, clutching Freud’s “Girl in Bed” painting to his chest. Author of Dangerous Muse, Nancy Schoenberger, suggests that throughout her marriages to brilliant but tortured men, she had the power to cruelly provoke their worst qualities and undermined their creativity with her razor-sharp wit, only made crueler by her alcoholism.

The year after Lowell’s death, Caroline’s eldest daughter Natalya died tragically and horrifically at just seventeen years-old. She had passed out headfirst in a bathtub, drunk while attempting to inject herself with heroin. People that knew Caroline wondered whether her first novel, The Stepdaughter, published two years before the tragedy in 1976, was partly biographical, based on her neglectful relationship with her tormented daughter. Blackwood’s follow-up, another partially autobiographical book, Great Granny Webster (1977) was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Modelled after her own childhood, during much of which she was raised by a series of negligent nannies on the grand austere family estate in Northern Ireland, Blackwood writes about a young girl who is sent to live with her great-grandmother in a great, decaying country house. According to Caroline, at one point, she was so hungry she was forced to beg scraps from the villagers. Her third novel The Fate of Mary Rose, describes the effect of the rape and torture of a ten-year-old girl on a small English village. In the 1980s, she wrote biographies of members in her former London clique, including Princess Margaret and Francis Bacon, while still drinking heavily and living alone in a former funeral home in Sag Harbour, New York. She died of cancer in 1996. All of her books are the darkest of fairytales.