Imagine being given 48 hours to pack up and leave for an unknown destination. What would you bring with you? What would you do with your house, your business, all your clothing and furniture? On February 25th, 1942, some 3,000 Japanese-American residents on Terminal Island in Los Angeles county were faced with this unimaginable situation. They were the first Japanese-American community forcibly removed to detention camps and the only Japanese-American community that was razed to the ground. Four years later, when a few of the residents attempted to return, they found that only two buildings remained of their once-thriving island home.

Before Terminal Island had a Japanese-American fishing village, it was a bucolic spit of land sandwiched between San Pedro and Long Beach. The Tongva people lived along the coast of southern California for centuries before Spanish explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo sailed into San Pedro Bay in 1542. After forcibly relocating the coastal natives to inland missions, the Spaniards named the island La Isla de la Culebra de Cascabel, or Rattlesnake Island. Yes, there were rattlesnakes there, especially after it rained. Despite the venomous vipers, a resort area called Brighton Beach sprang up on the island in the 1880s. A decade later, the Los Angeles Terminal Railroad Company bought the property for $250,000 and changed its name to Terminal Island, the last stop on the rail route from Utah to Los Angeles.

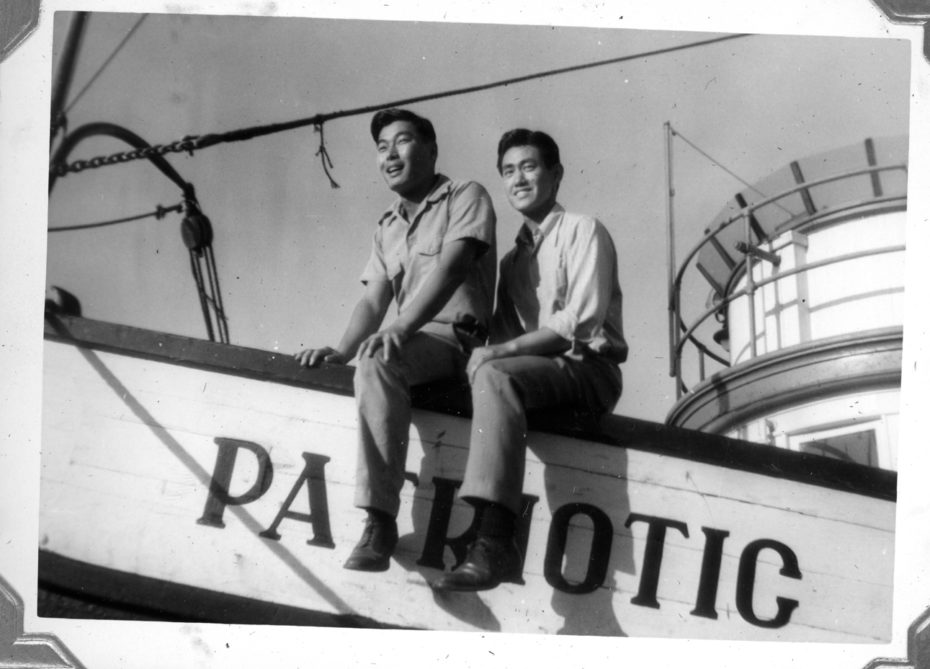

Around this time, a group of Japanese men who had worked for the Southern Pacific Railroad Company, moved to San Pedro Bay and began diving for abalone, a delicacy in Japan that could fetch a substantial sum of money. Despite increasing anti-Asian sentiment, a successful abalone fishing cooperative was established in White Point. Then in 1905, a California state law was passed prohibiting Japanese from fishing for abalone. Forced to find a different livelihood, a group of abalone divers moved to Terminal Island where they began fishing for tuna with long bamboo poles, the way it was done in Japan.

Meanwhile, the California Fish Company, which had been canning sardines on Terminal Island since 1893, had a problem. The sardine catch was in decline and they needed a new product. Seeing the ease with which the Japanese fishermen caught tuna, they turned their attention to canning and marketing tuna, which at the time was not familiar to the wider American public and only available fresh. Their solution was to steam the tuna white, pack it in salad oil, and market the canned tuna to housewives as an affordable substitution for chicken. Soon, tuna canning became one of the fastest growing industries in California and Japanese-American labor was at the heart of it.

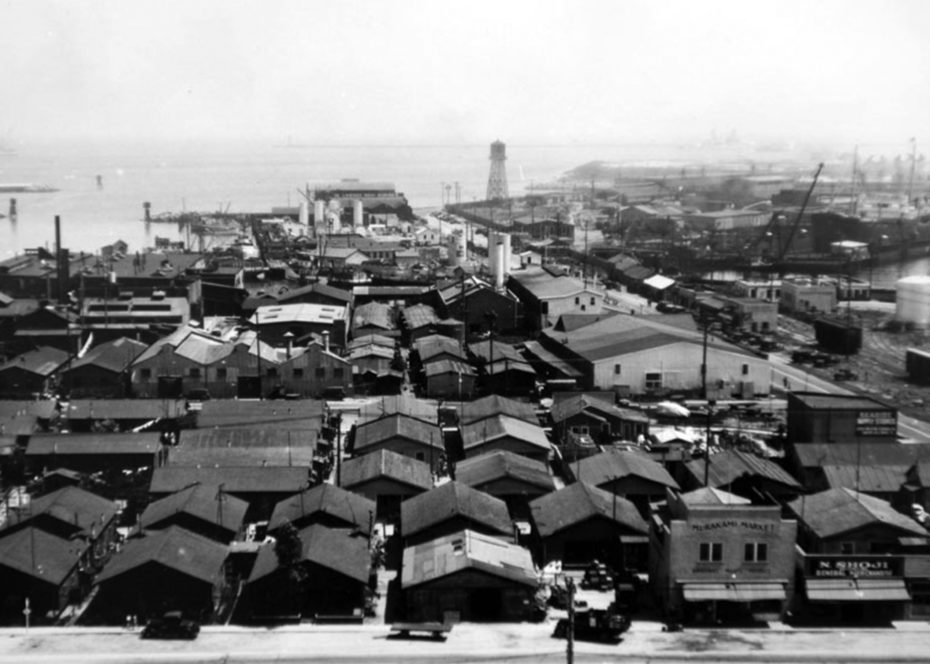

By 1907, there was a flourishing Japanese-American fishing village on Terminal Island. If this sounds charming and quaint, it wasn’t. Terminal Island was a company town, which eventually was owned by eight canneries. A notorious prison sat on one side of Fish Harbour. The other side of the harbour was lined with enormous factories. A block inland, the residential area was comprised of rows and rows of nondescript houses that looked exactly alike. The smell of fish permeated the entire island.

The canneries provided company-owned housing and offered the fishermen 49% of the money made from the catch. From 20 identical houses, the village grew to nearly 300 houses by the 1930s. The fishermen were joined by picture brides (similar in a number of ways to the concept of the mail-order bride), many of them from the Kii peninsula, where the men also came from. A way of life developed. The men were often gone for months, following tuna up and down the Pacific coast, from San Francisco all the way to Peru. When they returned with the catch, the women went to work in the canneries.

“The whistle would blow at 2 or 3 in the morning,” Tsui Murakami remembered, “Each cannery had a different number of whistles, so you’d lie in bed listening for your own. We’d take a bucket, a knife, apron and gloves, and go.”

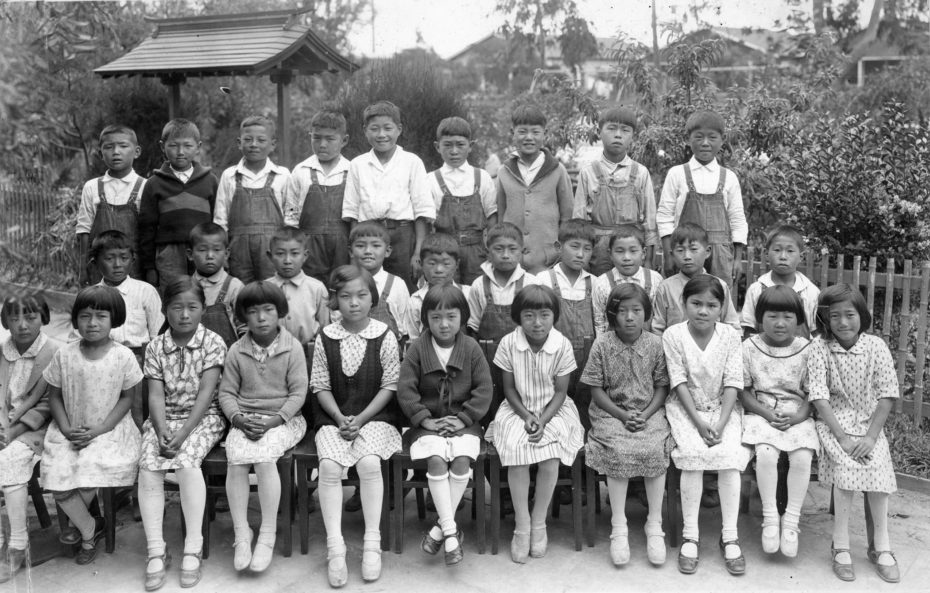

Due to the isolation and communal labor, the residents of Terminal Island became a tight-knit community. The Japanese-American residents called it Furosato, a nostalgic word for “old hometown.” They developed a unique dialect from a mixture of English and the dialect of Kii Province. They built a Baptist Church, a Buddhist Temple, and a Shinto shrine with a fox statue to guard the Torii gate. There was a movie theatre and a baseball team. Families took turns stoking the fire of a communal onsen or hot bath. There was an elementary school, as well as restaurants, grocery stores, an ice-cream parlour, and a clothing shop, all owned by Japanese-Americans. The calendar was full of cultural celebrations. Just before Christmas, the villagers collectively cooked and pounded rice to make mochi (rice cakes). Folkdances were performed on Girl’s Day and carp-shaped wind flags were raised on Boy’s Day.

December of 1941 began like any other on Terminal Island, with the Japanese-Americans buying gifts and stocking up on rice to pound into mochi cakes for the new year. Everything changed on December 7th when Japan launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

“We all said, ‘Pearl Harbor? Where’s Pearl Harbor?’ ” recalled fisherman Yukio Tatsumi.

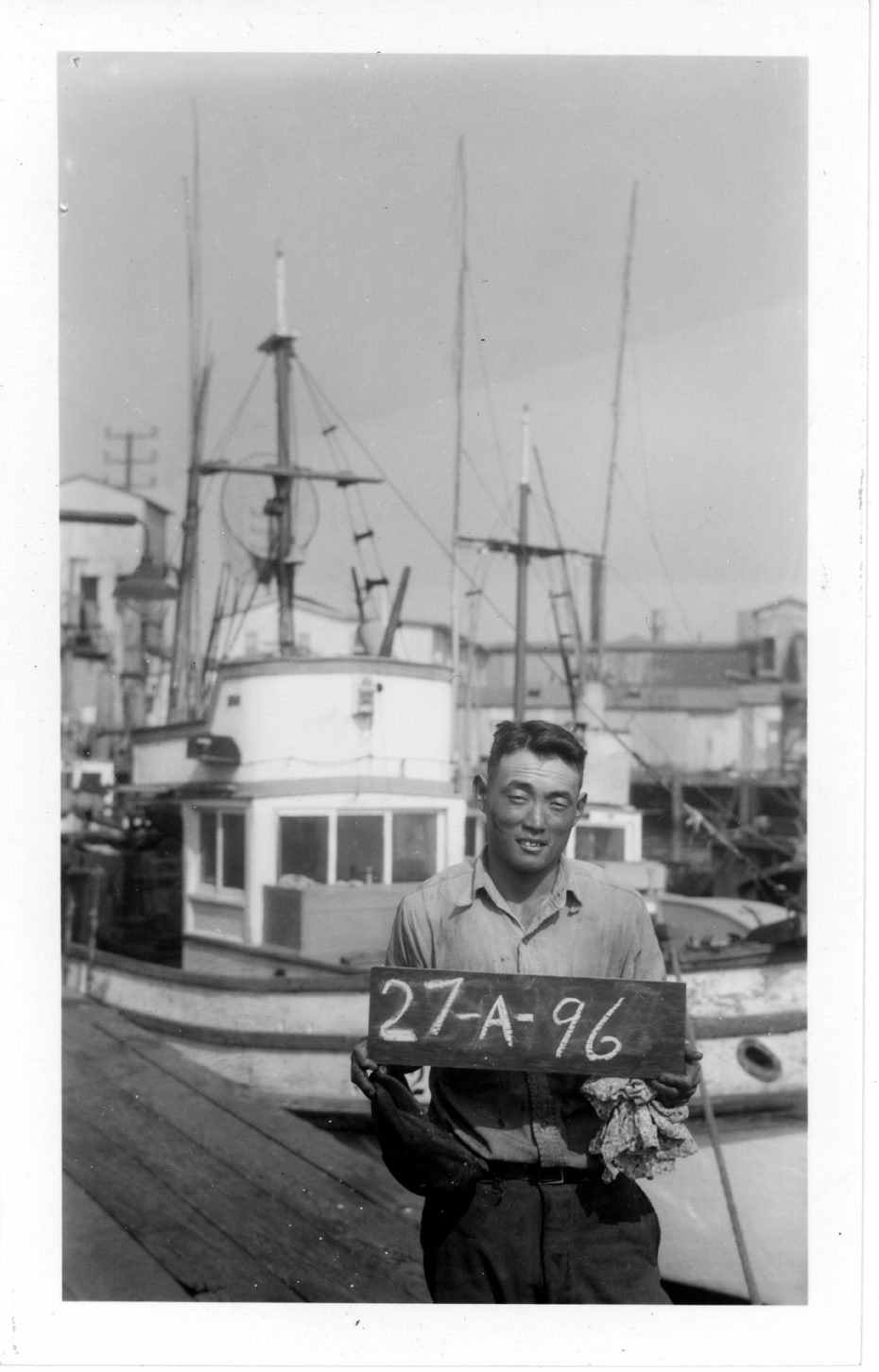

For the next three months, the villagers faced increasing hostility. Because there was a naval shipyard on Terminal Island, they were regarded with particular suspicion. Boats were immediately prohibited from leaving Fish Harbor. The FBI arrested all first-generation community leaders. All Japanese-owned businesses were forced to close. Homes were randomly ransacked. A curfew was imposed. On February 2nd, the FBI arrested all remaining men with a fishing license. The village was reduced to a huddle of frightened women and children surrounded by soldiers with bayonets.

Two weeks later on on February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 authorizing the military to remove enemy aliens from the West Coast. Terminal Island residents were given a 30-day eviction notice to evacuate. Then a Japanese submarine emerged near Santa Barbara on Feb. 23, 1942 and shelled an oil field, triggering a massive panic attack in Los Angeles the next night. The U.S. Army fired off 1,433 rounds at enemy aircraft as air raid sirens wailed and terrified Angelenos hid under their beds. In the morning, the Army was embarrassed to learn that there were no Japanese planes. It was just an extreme case of war jitters.

The day after the infamous Battle of Los Angeles, the eviction date on Terminal Island was abruptly moved up. Military policemen went door-to-door with an official notice ordering Japanese-Americans to leave the island within 48 hours. There was no information on where islanders should go after vacating, nor how they could transport their belongings.

“It was the most stressful, traumatic period of my whole life, being left with four children and no husband to help disburse two restaurant supplies within that ridiculous time frame,” restaurant owner Orie Mie later recalled. “Businessmen from all over came swarming around like vultures to take advantage of the dirt-cheap goods we were forced to sell.”

When Terminal Island was evacuated, the detainment camps had not yet been completed. A few lucky villagers managed to find shelter in hostels or Japanese organisations on the mainland. Most were forced to live in horse stables at a temporary camp created at the Santa Anita racetracks. Terminal Islanders spent two months in limbo before they were herded off to the Manzanar War Relocation Centre. They were soon joined by Japanese-Americans from Bainbridge Island in Washington state. A total of 120,000 Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast were incarcerated in 1942 without any justification. In contrast, 11,500 German-Americans were sent to detention centres throughout the war, all with known ties to the Nazi government.

What’s more, as the war progressed, approximately 33,000 Japanese Americans ended up serving in the US military during World War 2 (including 142 Nisei women who volunteered for the Women’s Army Corps). Second-generation immigrants born with American citizenship volunteered or were drafted to serve in all the branches of the United States Armed Forces, operating as segregated units of Nisei soldiers commanded by white officers. The 100th/442nd Infantry Battalion was a unit composed of men from Hawaii who entered combat in Italy in 1943 and suffered horrific casualties. They became known as the Purple Heart Battalion and among the most decorated units in U.S. military history. Approximately 800 Japanese Americans were killed in action during the war.

Soon after the Terminal Islanders were evicted, the Navy demolished the houses, the school, the Shinto shrine, the churches, and all the shops. No evidence was ever found of subversion or sabotage from the Japanese-American village, but it was nevertheless razed to the ground and fenced off.

Terminal Island industry continued as if the Japanese had never been there. The canneries replaced their Japanese employees with Mexicans and recent immigrants from Italy and Croatia. The shipyard was expanded and became a centre for the defence industry, where 40,000 women and men built 467 vessels during World War 2. But after the war, the shipbuilding facility was no longer needed and all of the industry slowly ceased. The last cannery closed in 2001, leaving Terminal Island an industrial ghost town of abandoned factories with rusted facades and broken windows. In 2012, the National Trust for Historic Preservation named Terminal Island one of the most endangered historic places in America.

Terminal Islanders spent two years in detention. Roosevelt’s exclusion order was rescinded in 1944 and they were released with $25 and a ticket to a location of their choice. With nothing left to go back to, Terminal Islanders scattered all over the United States. Some even went back to Japan. The few that tried to go back home to Terminal Island found nothing but a field of dirt behind a large fence labeled “government property.”

Though they no longer lived together, Terminal Islanders kept in touch and gathered whenever they could. In 1971, they formed the Terminal Islanders Club to preserve the memory of their community. Through the efforts of the club, the Terminal Island Memorial was erected in 2002 on Fish Harbor. Framed by a Torii gate, the memorial features statues of two Japanese fishermen, one hauling up a net, while the other crouches in front of their catch, gazing out to the abandoned warehouses where Furosato once was.

About the Contributor