When we hear the name Fabergé, we instantly think of those exquisite Imperial eggs; the mystery and intrigue surrounding their loss and rediscovery following the Russian revolution. But in truth, the goldsmith’s real and most potent love affair of the 20th century was one with flowers. The value of Fabergé flowers is enhanced by the fact that only about 80 flower and fruit studies are known to have survived, now valued at millions per piece. And well deserved, as these dainty depictions are so lifelike that they often rival reality. They too have been smuggled out of palaces, travelled across continents only to be forgotten with the passage of time, before turning up generations later in the most unexpected places. So as winter takes its grip once again, let’s instead take a virtual stroll through Fabergé’s overlooked secret garden of floral treasures…

The Queen Mother of Queen Elizabeth II, once said during an interview that she took great comfort in looking at her Fabergé florals to cope with the hardship and destruction Britain faced during World War II. “However awful the moment, it was so enchanting to see this charming and so beautifully unwarlike plant starting to tremble when most horrible things were approaching,” she said. Hyper-realistic and encased in tiny vases, their beauty is disguised in the pure simplicity of nature’s fleeting moments.

The Brooklyn Museum, New York – Sotheby’s

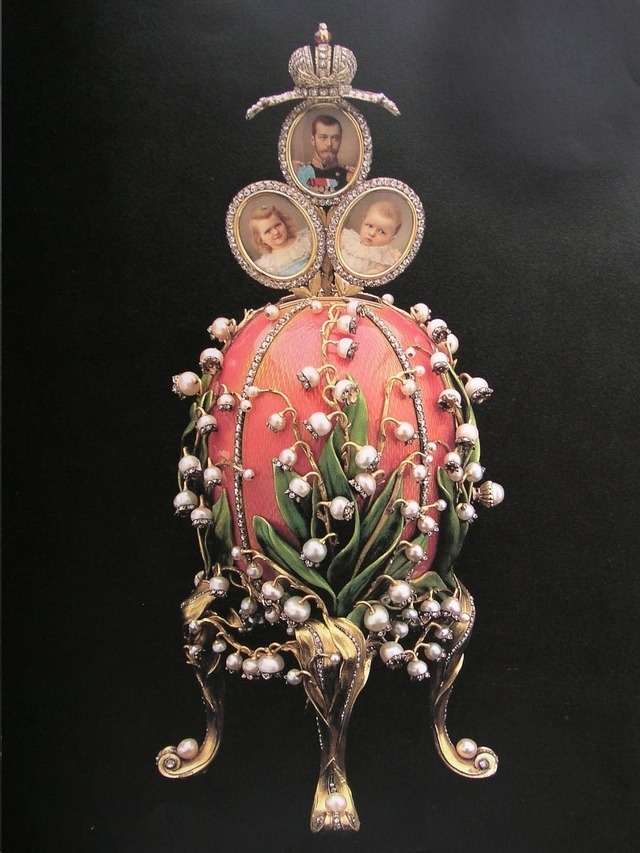

Peter Carl Fabergé was a Russian jeweller from St. Petersburg who found particular popularity within royal ranks, becoming the favourite of the Danish princess who became Tsarina of Russia Maria Feodorovna and her sister, Alexandra, who married Albert Edward, the future King of England. In fact, this connection is one that took Fabergé’s pieces to purvey the extremities of Europe and Asia. The two royal sisters were stricken with a love for Fabergé’s luxuries and a love for flowers that lifted their spirits living in foreign countries where the cold is unforgiving for at least eight months of the year, particularly for the Russian Empress. While Fabergé loved to dabble in Chinese and Japanese botany, his obsession was one with wildflowers often sprouting for a short time at the brink of winter and spring. Each is a depiction of Solstice, a tender awakening from winter’s slumber and transformation into the blossoming spring. “Flowers [are] a true Russian luxury,” noted the French poet Theophile Gautier.

To please his young queens, Fabergé took to the study of botany, plants, florals, herbs, berries, and more to depict them in beyond lifelike, delicate detail. This was also around the time of a renewed interest in floral perfumes during the Belle Epoque, giving flowers a true spotlight in all their expressions. And Fabergé was at the center of it all, demonstrating expertise with ingenious craftsmanship. The Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, who escaped the Russian revolution with her jewels to Bucharest and then to Paris, is known to have had one of the grander collections that numbered 33 flowers. Amongst the featured favorites of the Grand Duchess were cornflowers, forget-me-nots, cacti and a dandelion made of gold and diamonds on a gold stalk with jade leaves.

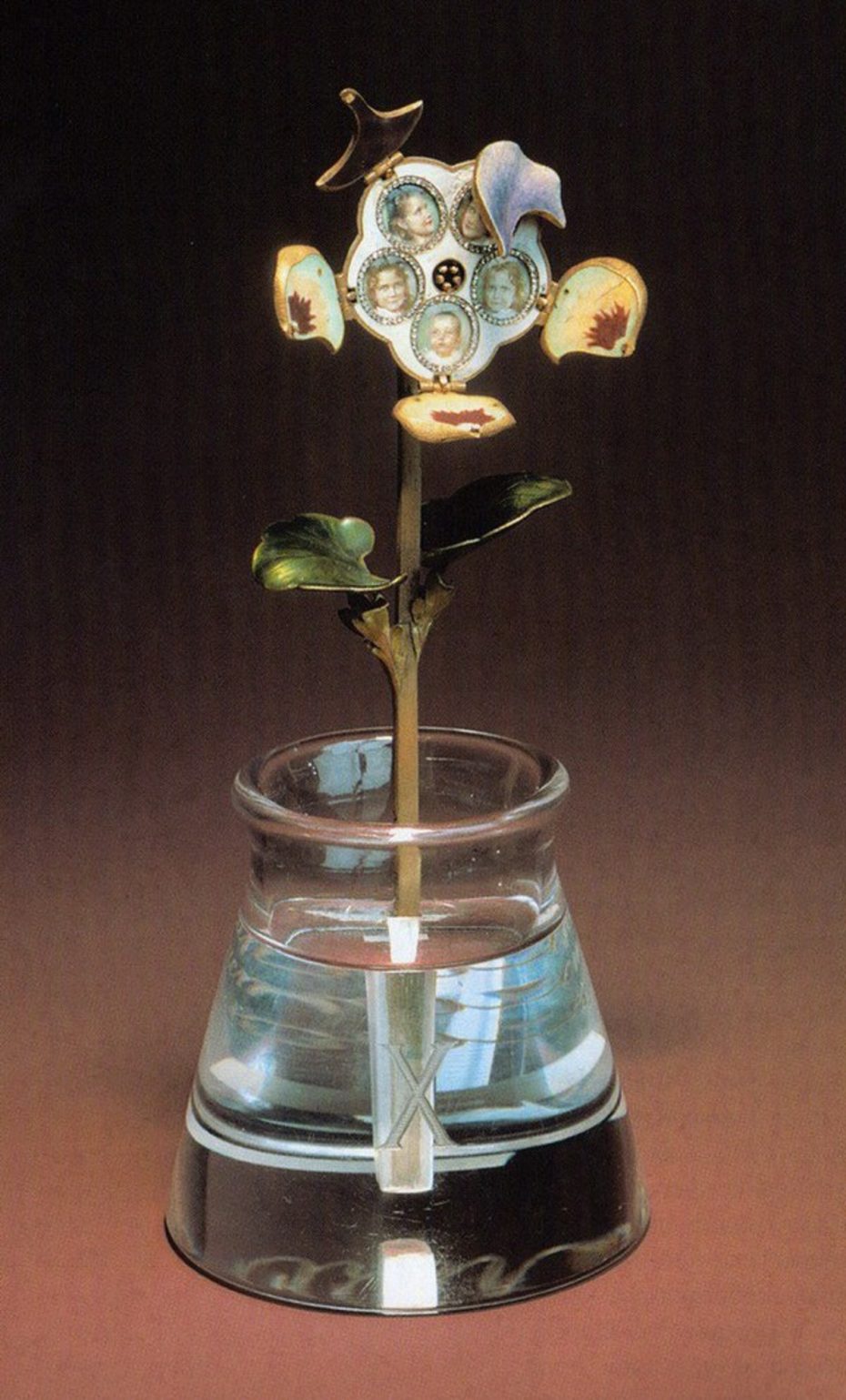

Each stem is seen as balancing on the rim of transparent glass, set in imitation water, depicted by rock crystal. Adorned with exquisite minerals including chalcedony, carnelian and agate, aquamarine and opal, jasper and obsidian, jade and rhodonite, these creations are further decorated with gold, diamond, rubies, and sapphires for that extra sparkle. Many of these elements were found in true rarity in the Ural mountains of Russia, making them all the more precious. Each finished piece is thus a marvel, a true work of the master looking to perfect reality and freeze it into fine jewellery.

The hunt is still on for the lost Fabergé eggs (eight Imperial eggs are still missing), but there were thousands of Fabergé pieces in the palaces of the Romanovs, most now scattered across far away lands in the many collections around the world now, or right under our noses. The BBC’s Antique Roadshow recently revealed the discovery of a Fabergé flower made with gold, diamond, and jade valued, which was valued at over £1 million, making it the most expensive Antiques Roadshow find. Two British soldiers brought the ornate piece to the show, claiming that it had been given as a gift to their army regiment following the Boer War. As it happens, Fabergé jewels weren’t only a luxury for the royal class, they were often gifted to wartime heroes and other deserving figures and indeed, the flowers had been awarded for a battle in South Africa to recognize the sacrifice of the soldiers that did not return from the war in 1904. The 6-inch long pear glosson sits in a crystal vase with transparent water offering the impression that new buds are just about to blossom.

Following the publicity of the unexpected discovery, not one but two other Fabergé florals emerged, wrapped in a tea towel of all places. The elegant ornaments had been stored inside a shoe box for 40 years until the owner spotted the story of the flower valued at £1 million on the Antiques Roadshow. She had inherited them from her family who had “lived in high circles in society”.

The first study is an extremely rare one of a Convolvulus or Dwarf Morning Glory with heart-shaped leaves made from Siberian jade, naturally. The second is a twig from a barberry bush. Queen Alexandra and Edwardian era hostess Lady de Grey were among the most important clients of the London Fabergé offices and they insisted on seeing the new pieces first for optimal choice. Both the pieces are engraved with the name of Lady de Grey’s daughter Juliet, which would indicate Lady de Grey beat Queen Alexandra to the punch.

Today the British Royal Collection contains twenty-six Fabergé flowers and belongs to Queen of England Elizabeth II, inherited from Queen Alexandra, who had been an avid collector like her sister Maria, the Russian Empress. The collection includes branches of mountain ash, blue cornflowers, wild cherry, raspberry and cranberry, wild daisies, chrysanthemums, carnations, pansies, and a miniature pine tree in a pot made of jasper.

Maria Feodorovna and her daughter-in-law, Alexandra Feodorovna (the last empress consort of Russia) actually lent their pieces at the Exposition Universelle in 1900 in Paris for the first time. They were immediately copied by other designers, but, Fabergé persisted, only raising the bar with more elaborate designs (although Fabergé’s skilled competitors have been largely overlooked).

Some of Fabergé’s best work was made during the 20th century and his surreal handmade artistry still took centre stage during the age of the motorcar, telephone and electricity. His snapshots of transient life would then make it into some of the most exclusive collections and continue to be part of the Royal Collection of Great Britain for generations to come. Over a century later, as his work is once again at the centre of cultural celebration with the major new Fabergé exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, who knows what treasures might turn up in someone’s attic for the occasion.

Fabergé in London: Romance to Revolution runs until May 2022 at the V&A Museum