Beauty is only skin deep. But what if it’s actually even shallower than you think, only a few microns of spray tan thick? The global cosmetics conglomerate L’Oréal has devoted over a 100 years to the titivation of our precious bodies and telling us ‘we’re worth it’ from billboards and glossy magazines. L’Oréal has also spent about as much time painting over, cutting out, blocking and concealing its own rather ugly wrinkles, warts and carbuncles from its, let’s just say, not-so-flawless past.

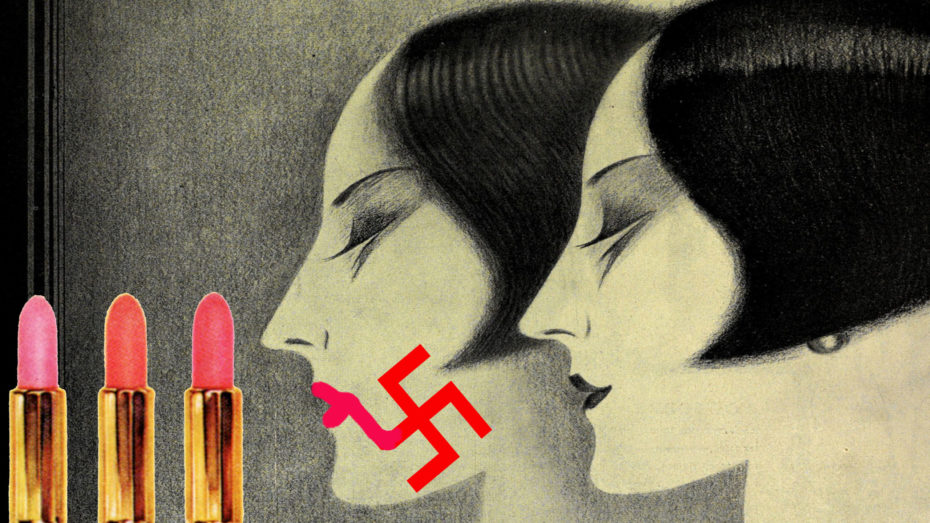

Today L’Oréal is a flagship holding company boasting a portfolio of 35 International brands including the likes of Lancôme, Yves Saint Laurent Beauté, Giorgio Armani Beauty, Kiehl’s, Cacharel, Diesel and Viktor & Rolf, with a turnover of over USD 1.37 billion a year, with roughly 88,000 employees in 2020. Beauty is evidently an ever-booming enterprise. The multibillion dollar global industrial manufacturer and retailer has always been in the business of surface embellishments of sorts, of painting and coating and glossing its human subjects in one way or another. Not so well known is the story of the oceans of paint supplied by a L’Oréal-managed company to the Nazi Germany war-machine to camouflage its killing machines, its battleships and U-boats. Rewarded with vast wartime profits, the founder of L’Oréal would plough this back into an empire dominating the post-war global beauty scene.

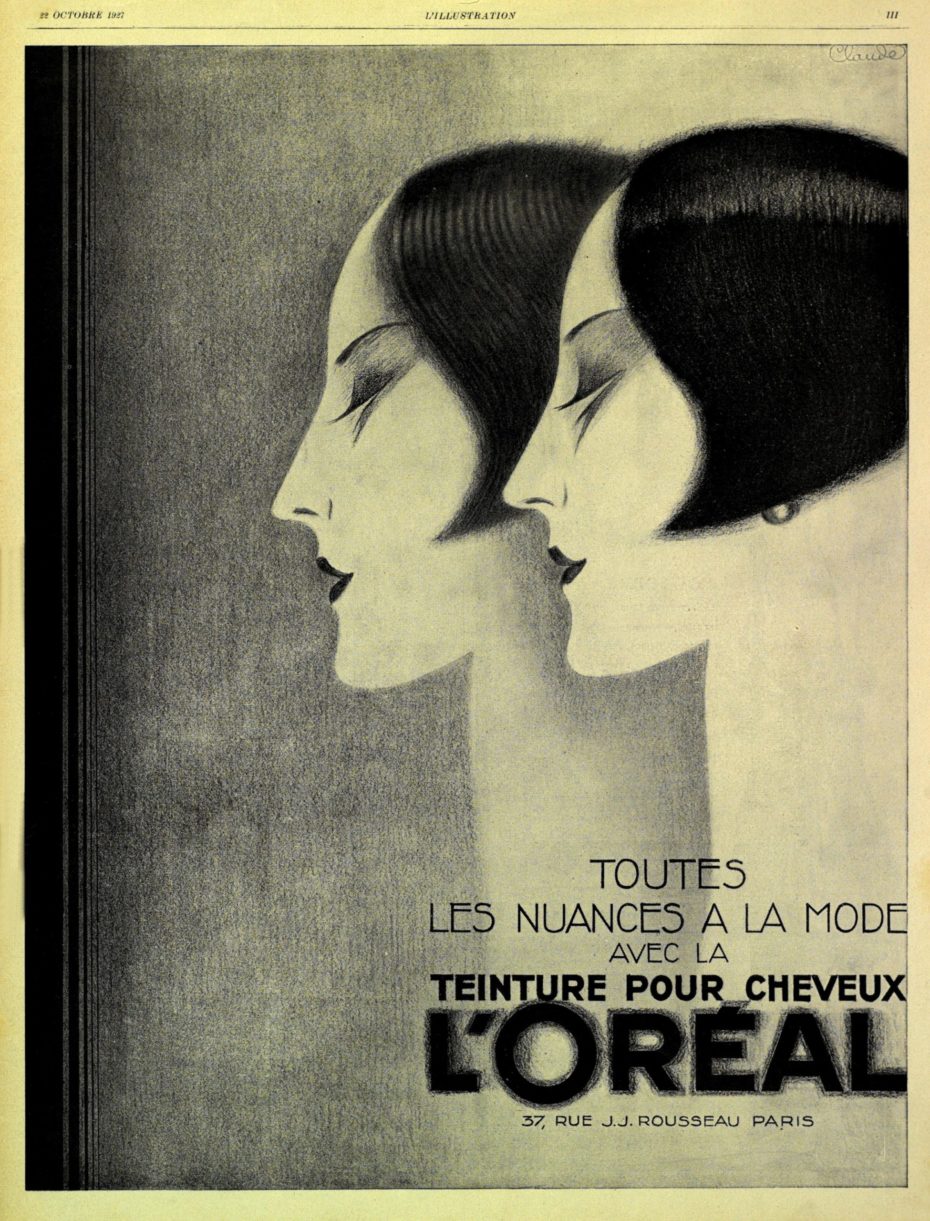

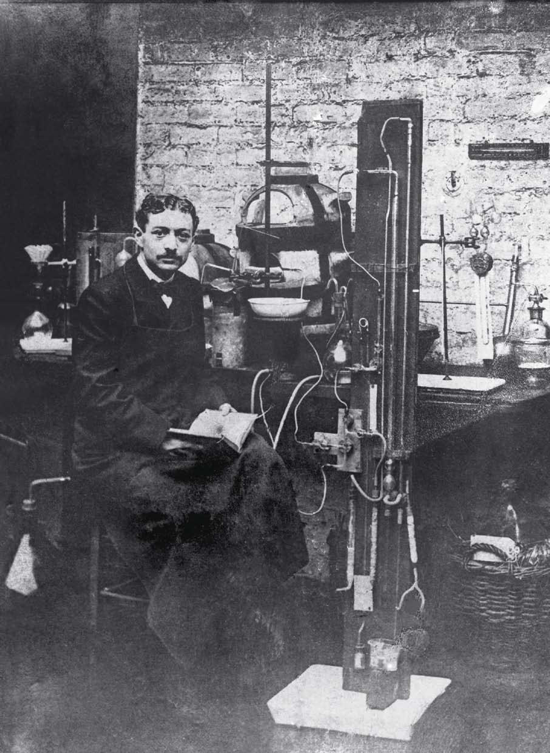

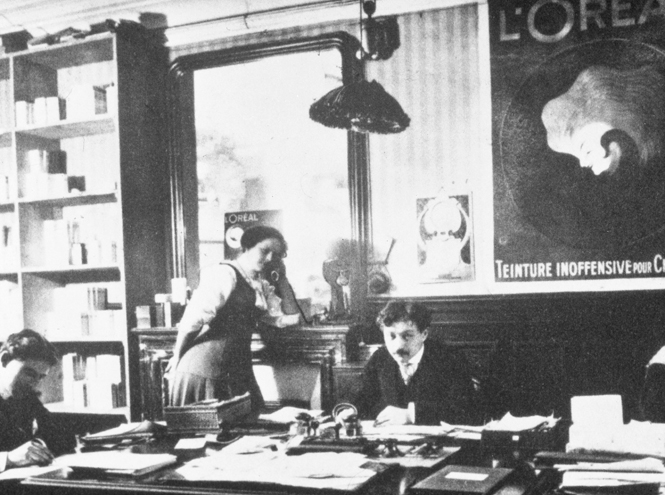

The company makes no mention of his dark past when celebrating his achievements on their website, but let’s step back in time and piece together how Eugène Schueller became a known fascist and Nazi sympathiser. The cosmetics giant L’Oréal (or ‘L’Auréale’ as it was originally named) was founded by Schueller in 1919 who discovered a new formula for making hair dyes. He was a French chemist who was in the business of researching, manufacturing and retailing women’s beauty products, famously gold hair tints. From humble beginnings, his empire went from a grand total of three chemists in 1920 to 100 in 1959 and 1000 in 1984. L’Oréal has grown exponentially to the present day.

Eugene Schueller also fancied himself a modern advertising mogul and would indeed become one of the founders of modern advertising. He was obsessed with the organisation of business and society. He explored socialism, capitalism and freemasonry. Tirelessly in pursuit of wanting to find new ways to organise labour and reward production, he lectured and published articles on politics and economics throughout 1930s. At the same time, France had elected a radical left-wing government in 1936, which introduced sweeping social reforms, notably shortened working weeks, paid public holidays and guaranteed wage rises. All of a sudden, women had some disposable income, a little more time to themselves, hence the desire, means and opportunity to pamper themselves in what was an expanding leisure market.

Although Eugene Scheuller enjoyed the benefits of the new French administration, the actual new politics were not to his taste. He didn’t like the democratic control and wanted the strongman dictator model as per Mussolini’s Italy, Franco’ Spain and Hitler’s new Germany. To further his right-wing agenda, Scheuller, now wealthier than ever, provided financial support to the French anti-communist and antisemitic movement La Cagoule (or ‘Hood’), a well-organised clandestine movement intent on a violent overthrow of the elected government, responsible for the assassination of a former minister and firebombing six synagogues. Scheuller held meetings at L’Oréal’s HQ for the fascist-leaning group, which soon enough, would support the Vichy collaboration with Hitler in Nazi Occupied France.

Under the Nazi invasion of 1940, France crumbled. Humiliated and broken, Eugene Schueller blamed France’s fall on the left and on democracy. Under German occupation, his writings and lectures became aggressively pro-Nazi and intolerant, extolling the political virtues and dynamism of Adolf Hitler’s Germany. Never neglecting an opportunity to expand his empire, Schueller used his right-wing associations to gain acceptance and financial opportunity in lucrative Nazi war procurement systems. He formed an association with the German paint company Druckfarben through his directorship of an intermediary company Valentine and made the sideways leap into another form of surface decoration. He went from from tinting women’s hair to tinting war vessels. A whopping 95% of the company’s wartime output was supplied to the German navy to paint its battleships, U-boats and the like. According to the Reich’s ‘Paint Plan’, Valentine was listed since 1941 in the ‘first category’ of paint suppliers. Between 1941 and 1944, at the height of the awful conflict in Europe, L’Oréal’s ‘sales’ quadrupled and Schueller’s personal wealth increased by a factor of 10.

With the fall of Nazi Germany in 1945, investigations into and trials of the Nazi leaders and their accomplices followed in order to provide some closure. In 1947, Schueller was officially listed as one of many ‘voluntary collaborators’ to Helmut Knochen’s, an SS Commander responsible for Death Camp deportations and numerous resistance executions. His vast war time income however, was never fully explained. The need for national reconstruction was politically more important and financial records of banks would be lost or doctored.

Eugene was charged and tried in the French courts but financial proof was lacking and a series of witnesses spoke in his favour, not to mention Francois Mitterrand, the then future French President, who would go as far as to profess that Eugene Schueller had financed the resistance. Eugene Schueller’s wartime management of L’Oréal was laundered by the French post-war courts. He was acquitted, and his company continued to prosper. Former members of La Cagoule who had also managed to escape prosecution from the French post-war authorities were hired as executives after the war, such as Jacques Corrèze, who, after serving half his 10 year sentence for war crimes, went on to serve as the American CEO of L’Oréal.

The political divide in Europe between the Western Allies and the Soviet communists accelerated from 1945 onwards and so did the race to control Germany, the new frontline state. In a bizarre twist, rather than the desire to punish Germany, the opposite was implemented and the race was on to rebuild Germany as a prosperous ‘free’ western state. Industries which had only a few months previously been smashed by Allied bombings were immediately resurrected, reconstructed and refinanced by the west.

The ‘whitewashing’ of European Industrial concerns was extensive. In the automobile industry, there was BMW, infamous for its use of Nazi slave labour and Dr Ferdinand Porsche, who was an officer of the Schutzstaffel (SS). IKEA’s founder, Ingvar Kamprad, was a known Nazi party member, Hugo Boss made Nazi uniforms, and BASF, the German company which used forced labour to provide mustard gas for extermination camps, became the largest chemical producer in the world today. All of these companies are cosily with us today; promoted, not punished, for their wartime behaviour. Eugene Schueller and his compatriots rode on the ironic crest of this wave. From 1961-1991, the German HQ of L’Oréal was on a property confiscated from Jews who were killed in the Holocaust. The post-war battle to recover this land lasted three generations. Contrary to the Allied restitution laws requiring all confiscated property to be returned to its rightful owners, L’Oréal held on to its land for as long as it could, until 1991, eventually paying restitution monies to a Jewish fund, but not to the dispossessed family. This strange, seemingly unjust outcome was the subject of Monica Waitzfelder’s book ‘L’Oréal a pris ma maison’ (L’Oréal Stole My House) of 2007.

Eugene Schueller’s family tale is equally Kafka-esque. His granddaughter, Françoise married a Jean-Pierre Meyers, whose rabbi grandfather died in the Nazi concentration camp at Auschwitz. She is currently listed as the world’s richest woman, owning a 33% stake in L’Oréal. She has raised her children as Jewish. The extraordinary L’Oréal family story is covered in Tom Sancton’s book The Bettencourt Affair, published in 2014.

As the media has slowly uncovered the awful reality of the collaborators to the Nazi regime, so have those collaborators issued their politically correct, pacifying statements and financial gestures in an attempt to keep the lid on their pasts. L’Oréal coined their famous slogan ‘Because I’m Worth it’ more than forty years ago, exploiting their success in a post-war consumer boom. It was clearly ‘worth it’ to Eugene Schueller and mega empire L’Oréal, but it’s somewhat more complex to put a ‘worth’ on L’Oréal’s shady past.