The story has everything a good drama needs: religion, sex, and murder. Judith was a beautiful young widow who saved Israel when the town of Bethulia was under siege by the Assyrian king Nebuchadnezzar. After a long prayer, she entered the Assyrian camp with her maid and gained the trust of the general Holofernes. She seduced him, served him too much wine, and cut off his head with his own sword.

Judith and Holofernes has been a popular subject in the art historical cannon since at least the 12th century, but no one had seen a depiction quite like Artemisia Gentileschi’s, which featured an unprecedented level of gore. Taking Caravaggio’s version even further, Artemisia shows the exact moment of the murder (others showed Judith as an idealized heroine before or after the act), sparing no bloody detail. So how did Artemisia end up painting such passionate and gruesome works in the 17th century, a time when women were barely permitted to paint at all?

Artemisia Gentileschi was born in Rome in 1593, the daughter of a well-known Tuscan painter Orazio Gentileschi, who had been a Mannerist until he met Caravaggio and became a full-flung Caravaggisti. Artemisia’s mother died when she was still young, leaving Orazio to raise his daughter alone. He did what any artist would do; he brought his child to his studio and taught her to paint. Orazio was shocked at how quickly Artemisia took to drawing and painting, even in comparison to his other apprentices and sons. She was producing professional work by the age of fifteen and by the time she was nineteen, he declared her talents as “peerless”.

Artemisia’s early work shows a precocious, talented artist interested in classical subjects. Her earliest known painting is Susanna and the Elders, which is impressive especially in it’s attention to the female form. Painted when she was 17, likely aided by her father in the organisation of the composition, it has been hypothesized that Artemisia studied her own body for the work, explaining its astonishing realism.

The painting depicts a biblical story in which two elderly men spy on the young Susanna, ask her for sexual favours, then accuse her of adultery when she refuses (which was punishable by death). Ultimately her name is cleared and the story is used to teach the virtue of modesty. The tale of innocence versus licentiousness unsettlingly foreshadows the events that unfold in Artemisia’s own life a year later…

There was of course a dark side to being a woman in a world mostly occupied by men. In 1611 Artemisia was raped by Agostino Tassi, a painter who worked with her father. Afterward he promised to marry her, a common resolution to rape charges at the time. When they were still not married after nine months, Orazio took Tassi to court. The records of the trial still exist, and Artemisia’s testimony is as touching as it is harrowing.

On the day that the rape took place, there had been another person in the house, a woman named Tuzia Medaglia who was a lodger and a sort of governess to Artemisia (Orazio would leave his daughter in Tuzia’s care when he left for extended periods of time). But Tuzia did nothing to stop Tassi, she even pointedly left the two alone that afternoon and didn’t come when Artemisia called for her.

During the trial Artemisia was tortured with thumb screws to ensure that she was telling the truth (it was believed that if a person can tell the same story under torture as without it, the story must be true). Ultimately the judge believed her and convicted Tassi of rape, banishing him from Rome for five years. Orazio and his daughter also left the city, in an attempt to escape the rumours that had begun to swirl around their family.

The Gentileschis moved to Florence, and to improve her tarnished reputation, Orazio promised Artemisia’s hand to a Florentine painter named Pierantonio Stiatessi. It was a loveless but convivial marriage that Artemisia tolerated while having other relationships on the side. Success came quickly in Florence; Artemisia was accepted as a court painter for the Medici family and created a network of the leading artists and minds of the day. She began to discover her preferred subjects and themes, “Judith paintings”, for example.

Artemisia painted different scenes from Judith’s story throughout her career, exploring various themes. Judith and her Maidservant, for example, shows a moment of sorority as two women carry away the head of the tyrant. The work could be an expression of Artemisia’s resentment towards Tuzia and her longing for female solidarity.

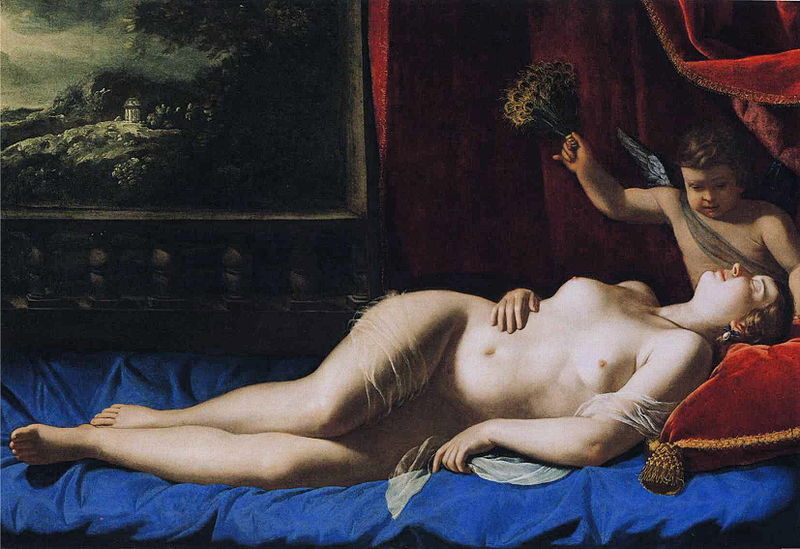

Another recurrence in Artemisia’s oeuvre is female sensuality, beautifully exemplified by Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy. Her female nudes possess an ease that can only come from first-hand experience and observation, showing the importance of the female perspective to the advancement of artistic depictions.

Feminine revenge, however, is a through-line in Artemisia’s work, seen in Jael and Sisera, another Biblical story in which a Kenite woman offers a fleeing Canaanite general shelter only to kill him by driving a peg through his head. This painting, along with Judith Beheading Holofernes, Salome with the Head of Saint John the Baptist, and Samson and Delilah were clearly influenced by Artemisia’s rape and trauma. By giving women power over men on her canvases, Artemisia was able to work through her own experience of powerlessness.

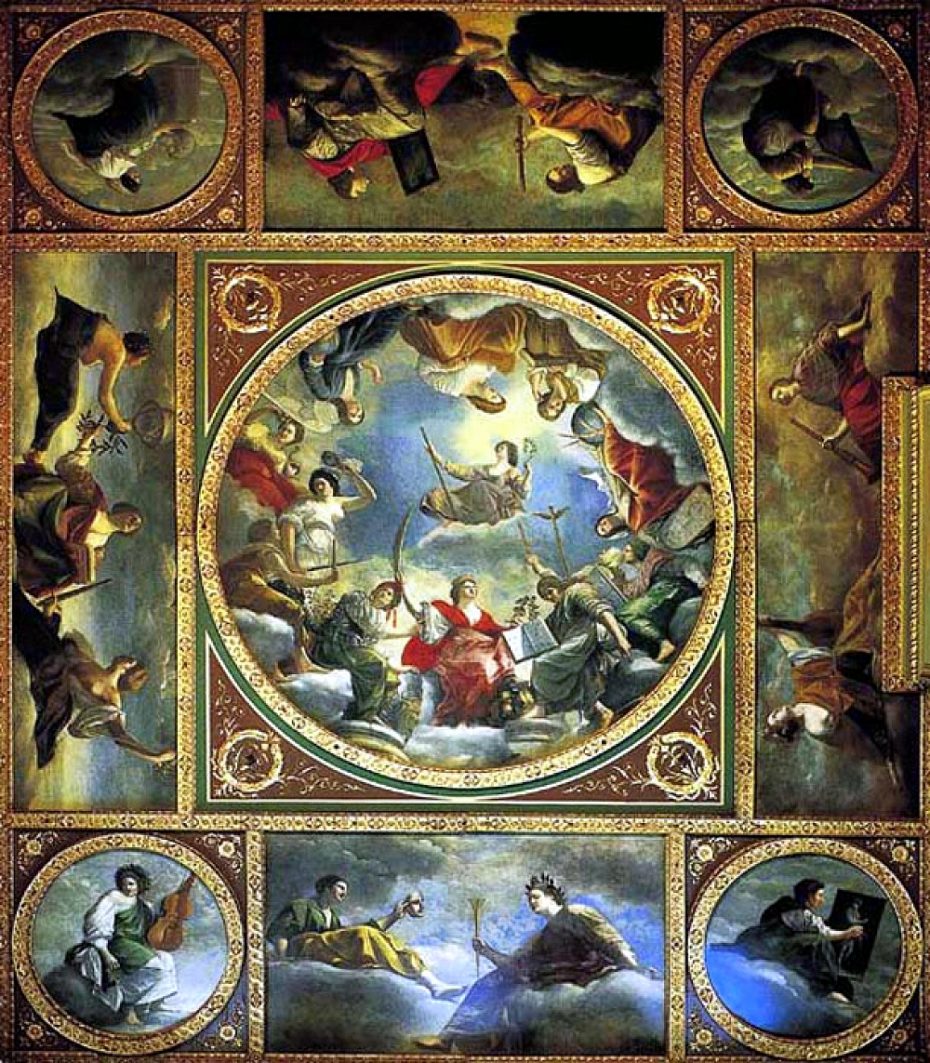

It’s possible that Artemisia also understood the importance of artistic branding. Her court case had made her famous, therefore making her revenge-fantasy scenes extremely marketable. Artemisia was both a victim, an artist, and a businesswoman. She was well connected in Florence, friends with Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger (the grandnephew of the great master), who commissioned her to contribute a panel to a ceiling for his palazzo, reportedly paying her three times more than any of the other painters involved in the project. Artemisia even corresponded with Galileo Galilei, which has led to some speculation that his projectile motion theories influenced her depictions of blood.

In this same period Artemisia had a staggering five children (two of whom survived to adulthood) and carried on a love affair with the nobleman Francesco Maria Maringhi. Her husband was aware of the relationship but permitted it due to Maringhi’s wealth and status. It has been suggested the men were even friends, judging by notes scribbled from Stiatessi to Maringhi on the back of Artemisia’s love letters. Artemisia taught her children how to paint, her daughters alongside her sons.

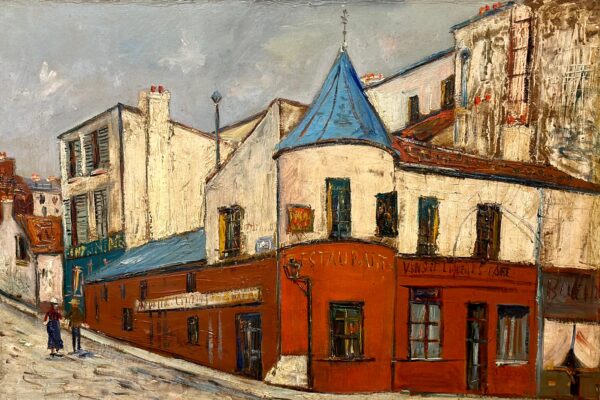

Soon, knowledge of Artemisia’s affair made its way around Florence, so once again, she returned to Rome. Riding off her Florentine success, Artemisia quickly had many patrons in the city, though the Papal commission still evaded her. Mingling with the international community in Rome, Artemisia built a reputation that spanned across Europe. Working in the High Baroque style (deep shadows and bright spotlights, scenes shown at their narrative climax) that was still at the height of its popularity, it was easy to find clients and commissions.

After Rome, Artemisia moved to Venice for three years at the end of the 1620s. There, she worked on commissions and added a Venetian, Titianesque depth to her palette, seen especially in the luscious fabrics she painted at the time (see the paintings Sleeping Venus and Esther before Ahasuerus). She next moved to Naples, a city still pulsing with the legacy of Caravaggio. Artemisia worked for the duke and the church and rubbed shoulders with other Italian masters. She remained in Naples until her death, the exact date of which is unknown, but is thought to be in the mid 1650s, perhaps during the Plague of 1656.

Artemisia was rediscovered in the 1970s, when the feminist art historian Linda Nochlin published the trailblazing article titled, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”

Nochlin uses Artemisia as an example of a possible “great woman artist”, who had sufficient talent but was subjugated by institutions that sought to exclude women. This resulted in a large increase in interest for Artemisia, cumulating in a record-breaking sale of her painting Lucretia at the Parisian auction house Artcurial in 2019 and a blockbuster retrospective at the National Gallery in 2020. It’s about time Artemisia’s name became synonymous with the Baroque masters, rolling off the tongue as easily as Caravaggio, Rubens, Rembrandt or Vermeer.

Connecticut’s Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art is currently hostin an exhibit “By Her Hand: Artemisia Gentileschi and Women Artists in Italy, 1500-1800”, running until January 9th.