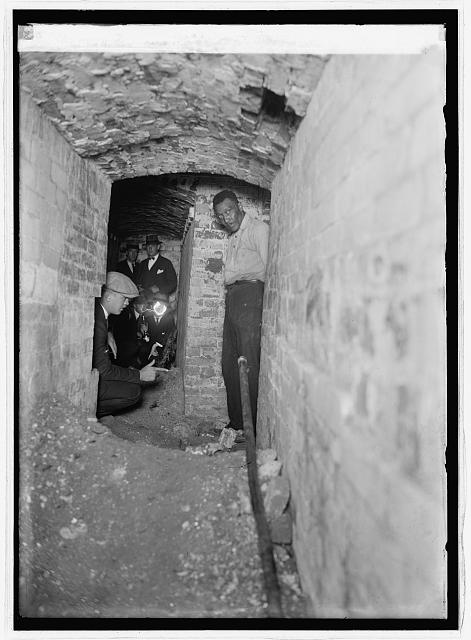

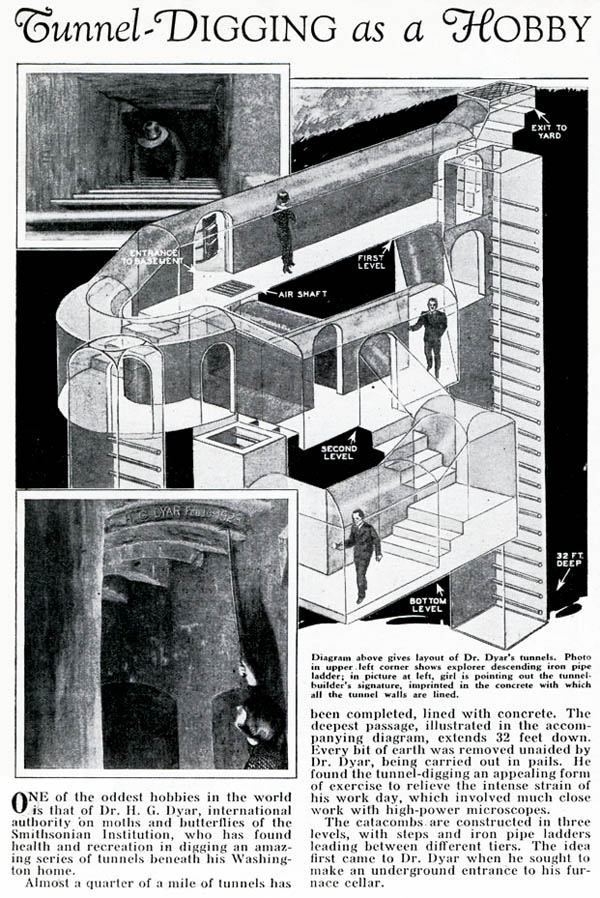

In 1924, a truck accidentally sank into a backlot in Washington DC, opening a sinkhole and revealing a labyrinth of tunnels. People were aghast at what had been found; there was talk of bootleggers and spies that would later make the front page of the Healdsburg Tribune, but no one had any answers. Eventually, a renowned entomologist of The Smithsonian came forward, a Mr. Harrison G. Dyar Jr., who admitted that he had built the tunnel fifteen years earlier and that it was a ‘’hobby of his’’. It had started in 1905, he explained, when he was digging the flowerbeds for his wife and thought, I could just keep going. When Dyar moved to another city, he continued with gusto, improving on his previous efforts with passageways of bricked walls and elaborate carvings and twisted stairwells. Tons of earth were shifted in a herculean solitary effort, and why? Because “some men play golf, I dig tunnels”.

People like hobbies, maybe I knit, maybe you paint, your partner might collect records, and the neighbour down the street whittles spoons, and so on. But what if your next-door neighbour developed a hobby of digging a warren of passageways beneath your feet? Hobby tunneling is the recognised subculture of amateur burrowers who essentially dig for kicks, excavating under the radar with nothing but their own shovels, picks, and strong backs.

Tunnels have been dug throughout history, caves for dwellings and storage; being below ground had its benefits in ancient times. As we developed, civil engineering projects used tunnels for irrigation and waste. The tunnel was then found to be a useful method of breaking into castles whose Lords just really didn’t want to open those gates. Then we had the subversive tunnels – good for hiding plunder, escaping from places, or just transporting contraband. While in modern times, it’s generally understood to be the domain of engineers and construction companies, tunnelling seems to found a growing civilian fan base…

In the 1960’s Mr. William Lyttle AKA ‘The Mole Man’ had decided a wine cellar was needed under his home in Hackney, London. He proceeded to dig, and kept it up for 40 years, his tunnels spiralling out from under his home in all directions like a spider’s web, 8 meters deep and 20 meters long. Lyttle, unmarried was something of a hermit. He’d worked in civil engineering but his major project seemed to be his covert tunnelling operation. As Lyttle’s house fell into disrepair around him, he continued to dig, but eventually, after many complaints, the council intervened. A temporary eviction notice was served and Lyttle was ousted, the engineers moved in and filled his beautiful tunnels in with concrete (and then charged him £100,00 for the trouble). His answer when asked why he’s spent so much of his life underground? ‘’I just found a taste for the thing’’. This blasé response seems synonymous within the world of hobby tunneling; they can’t quite understand what all the fuss is about.

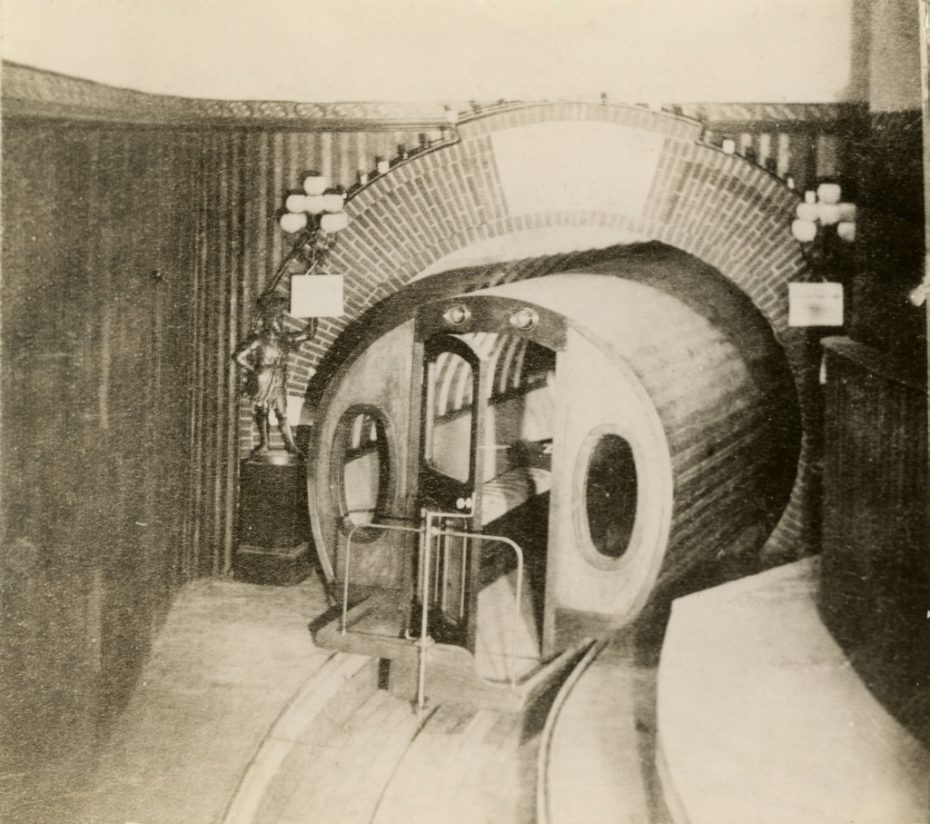

Secrecy is another common and presumably necessary trait amongst enthusiasts to prevent local authorities from intervening on unauthorised personal civil engineering projects. Perhaps one of the most sensational secret tunnel stories took place under the streets of New York City in the 19th century, when inventor Alfred Beach created an entire pneumatic subway demonstration system. With no initial political support for the project, he failed to get any permission, but he just went ahead and did it anyway (pretending he was building a smaller postal tube system which he did have a permit for). Once completed in 1870, the subway opened for demonstrations, running under Broadway from Warren Street to Murray Street.

Although the public showed initial approval, by the time Beach finally was able to gain permission to expand the stock market crashed and the subway was closed down within the year. It was boarded up and forgotten about, and the building that housed its entrance burned down. Decades later, New York was building the real subway system we know and use today, and by chance, the city’s diggers broke into Beach’s old abandoned pneumatic transit tunnel.

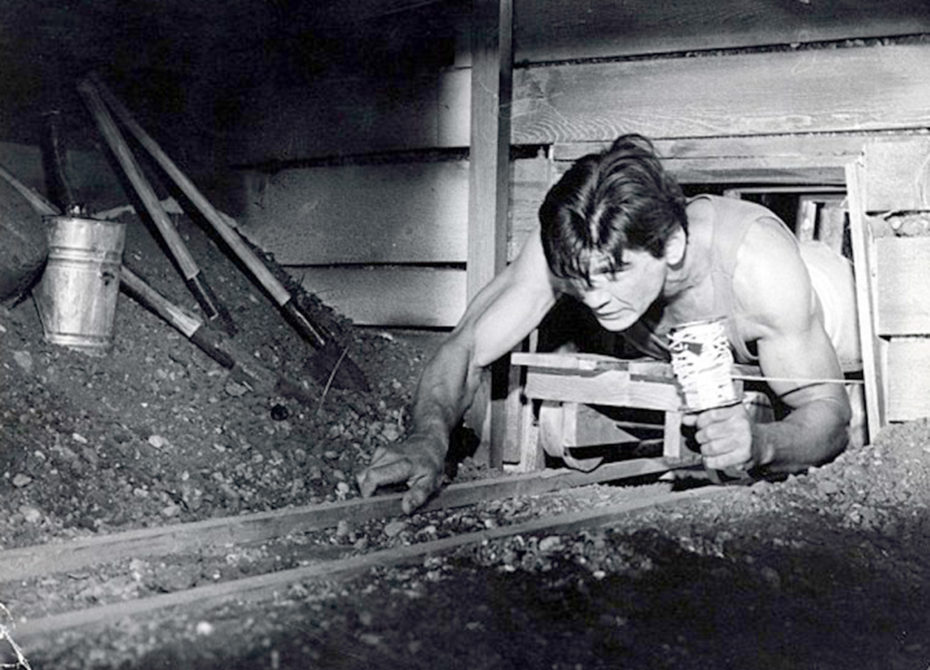

Mr. Seymour Cray ‘The Father’ of the supercomputer, like to tunnel too. Not satisfied with using his huge intellect for the advancement of computer technology, also decided pick up a shovel and get digging. Cray explained that when he was tunnelling his “mind was free to work on his computer problems”. He also allegedly claimed that elves came to help him with these underground calculations. They were said to have appeared after Cray tunnelled under the nearby woods. Some say PR-savvy colleague fabricated this fanciful anecdote to accentuate Cray’s quirky persona and thus promote the company. Either way ‘Cray’s Tunnel’ begs the question: can monotonous physical exertion open a door to a subconscious pit of enlightenment?

Despite the hours of back-breaking work, tunnel hobbyists for the most part, don’t want to stop, and cannot stop thanks to their underground addiction of sweat and toil. And of course, tunnelling is no easy task for the uninitiated – there is soil type to think of, props and shoring to prevent cave ins, and pumps to drain the water from digging in an area with a high water table. With the clandestine nature of the hobby, who knows how many amateur excavators may have been lost.

Someone who knew all about tunnelling is South American ex miner Manuel Barrantes. In the 1970s, Mr. Barrantes traveled to 17 countries in over 2 continents, and on these wanderings, he encountered people living in hand-built caves. He decided he too wanted somewhere environmentally sound to live, away from the pollution and the noise of the modern world. After some trials on some volcanic rock in Costa Rica, he went to work chiseling and removing debris, creating tunnels and caverns. Some 12 years later, what has been produced is a curved organic twisting eco dwelling that looks like something Gaudi may have envisaged. It has now become a local tourist attraction, adorned with murals and trinkets, stretching over 400 meters and boasting 25 rooms.

Not all tunnelling enthusiasts have been known to do the dirty work themselves. Take John Bentinck, the 5th Duke of Portland, also known as the ‘burrowing duke,’ who built 24 kilometres of tunnels and lavish rooms beneath his English estate, Welbeck Abbey during the 19th century, which included a ballroom & picture gallery, a billiards room, and a library.

Of course, the English aristocrat did no digging of his own and hired workmen to construct his extensive subterranean network, which still lies beneath the Abbey today. The Duke was a bit of a recluse however, and used the tunnels to roam his property unseen. The ballroom and underground entertainment spaces were never used.

If you watch one of the many hobby tunnelling videos YouTube has to offer, you can learn the basics, you can explore other people’s tunnels, and you can even watch as the tunnels are dug. There’s something slightly soothing about watching them – perhaps because you aren’t the one with the pick in your hand.

We contacted someone who is currently excavating his personal tunnel just outside of Los Angeles. John has been digging now for 5 years, and his tunnel currently measures in at 10 meters deep and 60 meters long. He’s dug it entirely with hand tools and believes ‘’if I have to exercise to keep healthy, I may as well dig a hole ‘‘. He’d been lowering his raised garden beneath the concrete of his patio to help with drainage and, ‘’well, below ended up being a bit lower than really necessary.’’ The tunnel has several branches and three stairwells leading out, and John has even installed a lift. At one point, the tunnel passes under his pool, so john thought he’d dig down on the pool and add an aquatic skylight. The shimmering light can be seen at the bottom of one of the stairwells giving an eerie wash of colour as you descend 10 meters down. So far he’s had no problems with the local authorities, and his friends and family? They agree he’s dug a ‘big hole’. We asked John just how far he plans to go? ‘’I plan to dig the rest of my life.’’