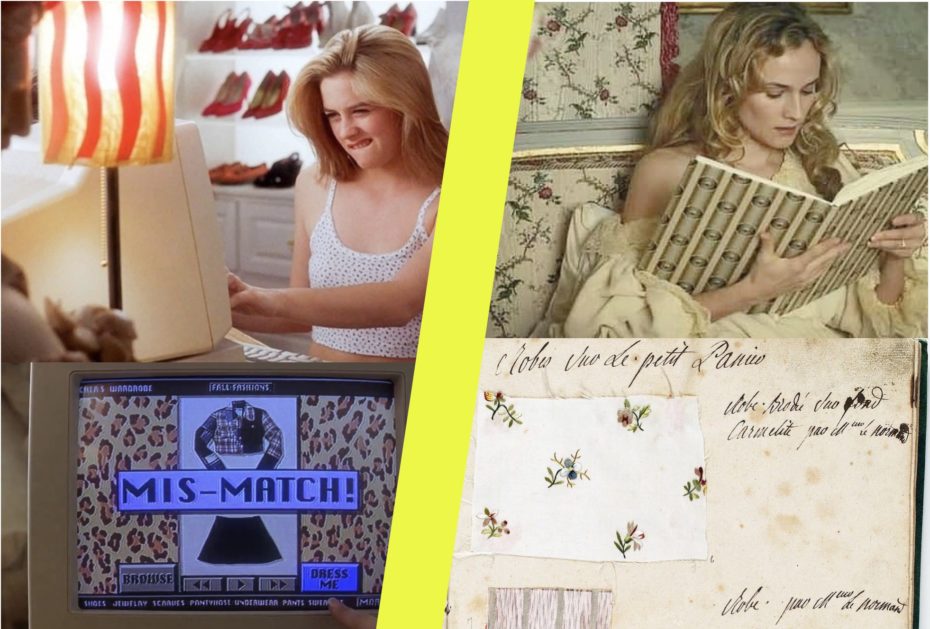

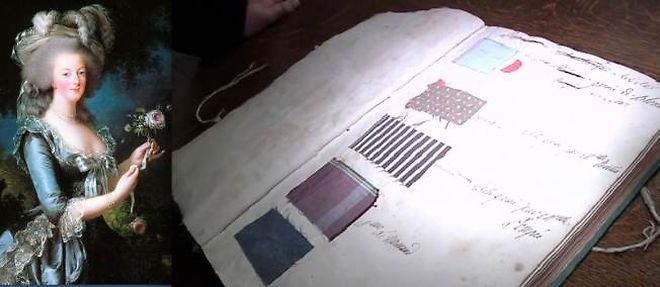

Ask any millennial with a heartbeat for fashion about the 90s cult-classic film, Clueless, and watch their eyes light up as they recall Cher Horowitz (played by Alicia Silverstone) and her “way normal” morning routine of mixing and matching pieces on her desktop computer to pick out an outfit for school from her revolving dream closet. Writer and director Amy Heckerling came up with the digital concept that enamoured teenage girls everywhere, and more than 25 years later, still feels very much like a scene from the future. But let’s step back about two-and-a-half centuries to the bedroom of another fashion heroine, where Marie Antoinette, the Austrian princess and the wife of King Louis XVI, would still be dozing in her extravagant four-poster canopy bed at the palace at Versailles. Her senses are slowly being awakened to the fragrance of fresh flowers, exotic aromatic oils, perfumed sachets and pot-pourri dotted around the gilded boudoir. While still propped up by silky pillows, she’s presented with her prized fashion bible, the Gazette des Atours, a billowing compendium of fabric swatches that represents every conceivable garment in that vast arsenal of hers, a securely colour-coded and catalogued wardrobe…

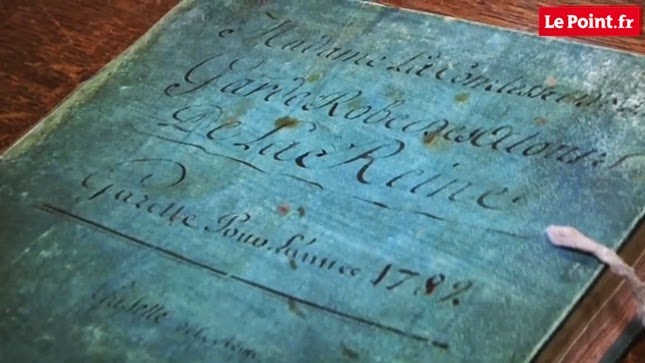

Preserved in the French National Archives today, the Gazette des Atours was the queen’s wardrobe book, a special scrapbook in which Marie Antoinette’s Mistress of the Robes, Geneviève de Gramont, the comtesse d’Ousun, pasted fabric swatches of the numerous outfits that belonged to her majesty. Every day the Gazette des Atours would be handed to the queen together with a pin cushion and pins, for her to indicate her choices of outfits for the day. Once the queen had made her choices, porters would be despatched to the three huge chambers that contained the closets stuffed full of billowing gowns. They would identify the outfits by their classification and cart the outfits back in huge baskets covered in green taffeta cloth.

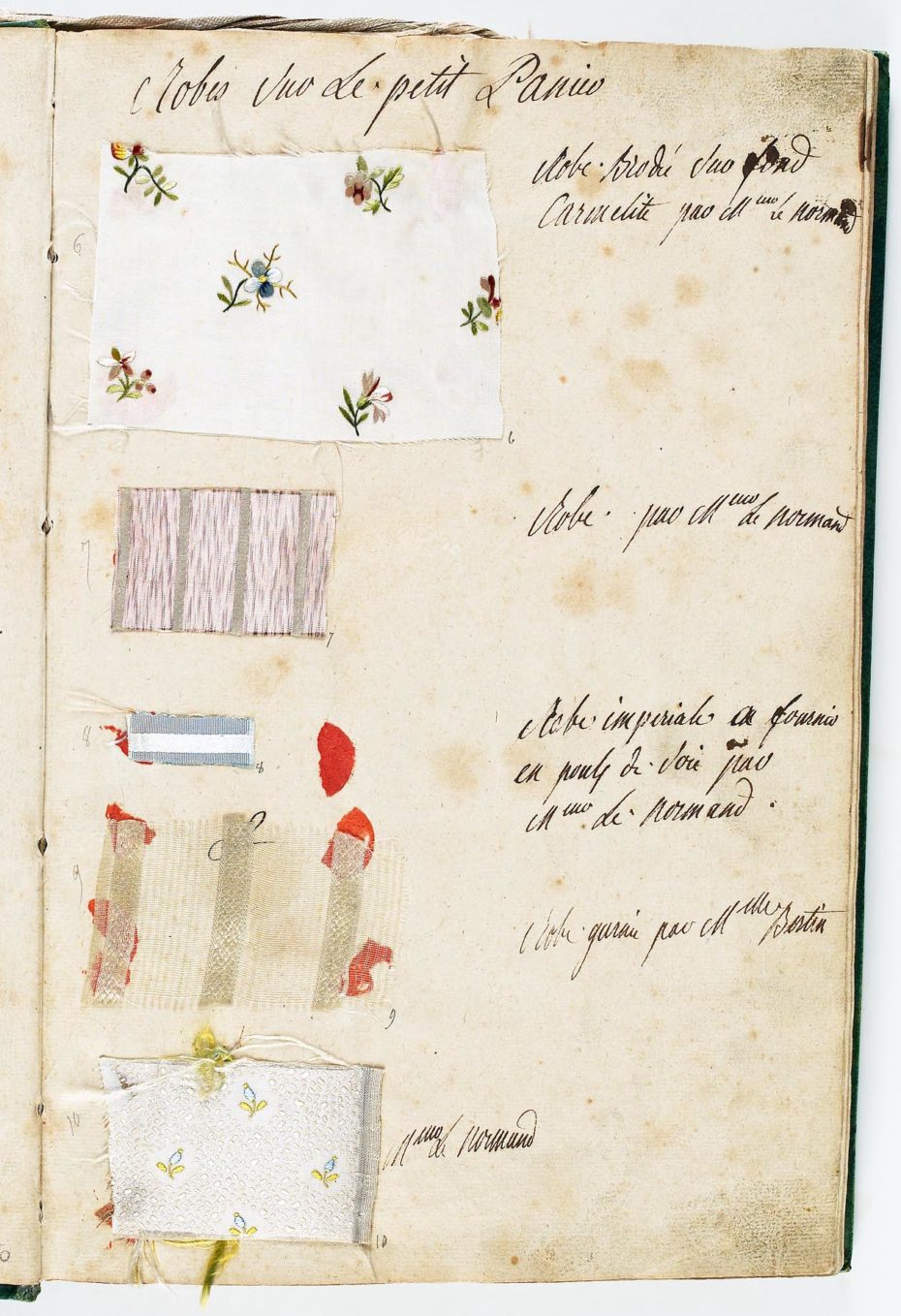

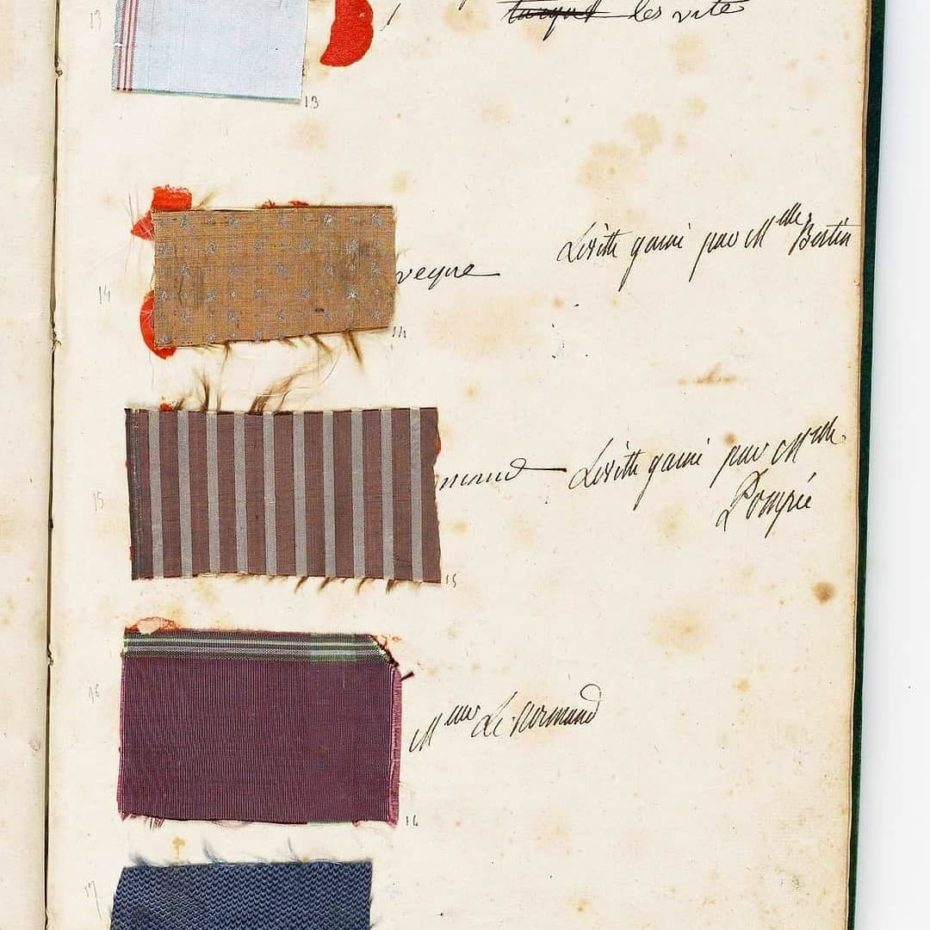

Allegedly, traces of the daily pinpricks that Marie Antoinette made in her Gazette des Atours can still be detected in the pages of the wardrobe book. In recent years some of the pins she used have actually been found in the floor boards of her bedchamber at Versailles. It’s said the queen especially adored striped and flowery fabrics, a sartorial trend that was followed by all the women of the court at the time. Cryptic notes beside each sample described the style of the dress – such as ‘grand paniers’, ‘anglais’, ‘turc’, ‘redingote’ and ‘levité’ which conjures up a mental picture of the end-product. As for colours, we know now that Marie Antoinette had a penchant for blues, deep purples and pinks, all shades that would have beautifully complemented her strawberry-blonde hair and powdered face. Antonia Fraser, who wrote the biography Marie Antoinette (2001) details the subtleties and nuances of the Gazette des Atours…

“Each outfit is categorised and accompanied by a tiny swatch of material. There are samples for the court dresses in various shades of pink, in shadowy grey-striped tissue and in the self-striped turquoise velvet intended for Easter. But what is notable is the preponderance of swatches for the more casual clothes, the loose Lévites (wrapped gowns with a sash) shown together on one page in an array of colours, from pale grey and pale blue through to the much darker shades of maroon and navy, sometimes with small sprigs embroidered between the stripes. There are redingotes (from the English word riding-coat) in the same palette of blues, as well as a particular mauve marked Bertin-Normand, coupling together the names of the couturier and the silk-merchant. Swatches for the so-called ‘Turkish’ robes are shown in self-striped pink and very dark mauve, for the robes anglaises in turquoise and self-striped mauve as well as dark maroon striped in pale blue. One swatch of material, supplied by the other celebrated silk-merchant, Jean-Nicholas Barbier, uses the Queen’s favourite cornflower to good effect, set in a design of wavy cream-coloured stripes. (Marie-Antoinette, p.208).

These wardrobe books were by no means anything out of the ordinary for the royal families of Europe at the time. A second wardrobe book (dating from 1792) that belonged to Madame Élisabeth, the youngest of Louis XVI’s sisters, is held at the the Domaine de Montreuil, Madame Élisabeth’s residence in Versailles. The swatches inside are simpler patterns in light silks and cottons, and unlike Marie Antoinette’s collections, there were no brocaded silks. Also, archivists note that this book is somewhat tidier than that of our impetuous queen, and for some reason, there are no pin pricks in Élisabeth’s version.

There are alternative theories regarding wardrobe books too. Director of the National Archives Museum, Pierre Fournié, reckons the wardrobe gazette may in fact have been no more than an accounting document, used to verify that suppliers have delivered creations on time.

Incidentally, to further embroider the textile tale, there was intense nationalist rivalries in the manufacture of fine and elaborate cloth in Europe. France had been the leader, but with the rising industrial power of Great Britain in the later 18th century, the bar had been raisd. Indeed, the French, while at war with the Britain, paid spies to report on the English textile industry and steal samples, with description notes upon sources of linens, damasks and velvet. The display of fine and contemporary fabric was clearly a subject of national pride. One can only speculate whether the French crown surreptitiously sneaked their cloth spies to Britain to ensure their queen, Marie Antoinette remained the leading fashion icon of the day.

But we all know how this story ended: our irrepressible regal fashionista Marie Antoinette came to a sticky end at the age of 37 when she was marched from her cell in the Conciergerie, the 14th century fortress on Paris’ Île de la Cité, and paraded in an open cart to the scaffold in the Place de la Révolution with onlookers screaming obscenities at her. You’d think impending death would make you reconsider your fashion obsession, but you’d be mistaken in this case. The mourning attire that she’d been wearing since her husband’s death had by now grown pretty shabby, but somehow – knowing she’d want to make a lasting, final, victorious and memorable fashion splash before her head rolled – she managed to pull a rabbit out of a hat and produced an all-white ensemble of chemise, petticoats, morning dress and a bonnet. Prior to that, the Jacobins’ chief executioner, Citizen Sanson, arrived to cut off her hair, which was said to have turned white overnight in June of 1791. A defiant Marie Antoinette, no doubt a fabulous vision in white, was executed by the guillotine in 1793.