When the grand mansions of America’s Gilded Age were being built, no expense was spared; from the finest stones for the exterior to decorating every nook and cranny inside with extraordinary, lavish detail. The same luxury was applied to the entertainment on offer; after all, being a member of America’s wealthiest families meant that a lot of leisure time was involved. William Kissam Vanderbilt III’s mansion on Long Island’s Gold Coast came replete with a splendid outdoor 70,000 gallon saltwater pool, the waters drawn from the Sound estuary itself. Elizabeth Schermerhorn Jones’ grandiose gothic mansion in the Hudson Valley was installed with a complex piping system that delivered cold, draft beer directly to the outdoor tennis courts. But perhaps the height of luxury for the Gilded Age elite, was to have your own private bowling alley. Normally the preserve of the salubrious saloons and beer halls you’d find in Manhattan from the Bowery to Hell’s Kitchen, but here bowling was elevated to a gentlemanly sport. To the after dinner pursuits of brandy, bridge and billiards, the fortunate elite could add a few frames of bowling.

Whether tucked away in basements, or found in their own bespoke buildings on vast estates, these alleyways were a far cry from the beer-soaked lanes of the bar room, or the pastel chic of the 1950s bowling centres, when bowling ruled the roost as America’s favourite small town past time. Often just two lanes of sumptuously polished wood, with a simple chalkboard for scoring, these quaint old bowling alleys were free from mechanical engineering: sloped guttering would return bowling balls by way of gravity, and pin boys were employed to manually reset the pins (more on them later). This was bowling the old fashioned way, where not much had changed since the first Dutch settlers of New Amsterdam portioned off a piece of land in what is today Lower Manhattan, and called it Bowling Green.

Our guide to the wonderful world of old wooden bowling alleys going forward, is photographer and avid bowler Kevin Hong, who has tracked down and photographed over a hundred old alleyways, in a project he calls Maple + Pine.

“I’ve been bowling as long as I can remember. My parents were bowlers and they met in a mixed bowling league,” explains Hong. “I felt that old, small bowling alleys needed to be documented, and their stories told. The old ones I’ve discovered are mostly unchanged…It’s like stepping into a time machine, a living museum experience. I like them for the same reason that people still go to drive-in theatres or old soda fountains. It takes you back to a simpler time, when we did not depend so much on screens and bandwidth ruling our lives. There’s something primal about an analog activity such as rolling a bowling ball on a wooden lane”

ROSELAND COTTAGE

Our first stop in discovering America’s forgotten wooden bowling alleys is at its oldest: Roseland Cottage in Woodstock, Connecticut, was built in 1846 for wealthy silk merchant and newspaperman, Henry Chandler Bowen. More mansion than cottage, the imposing Gothic Revival style was offset by the house being painted a whimsical bright pink.

Said to be one of the best preserved Victorian summer houses in America, Roseland Cottage came with an aviary, beautiful boxwood-edged parterre gardens and what is thought to be America’s oldest surviving indoor bowling alley.

THE FRICK

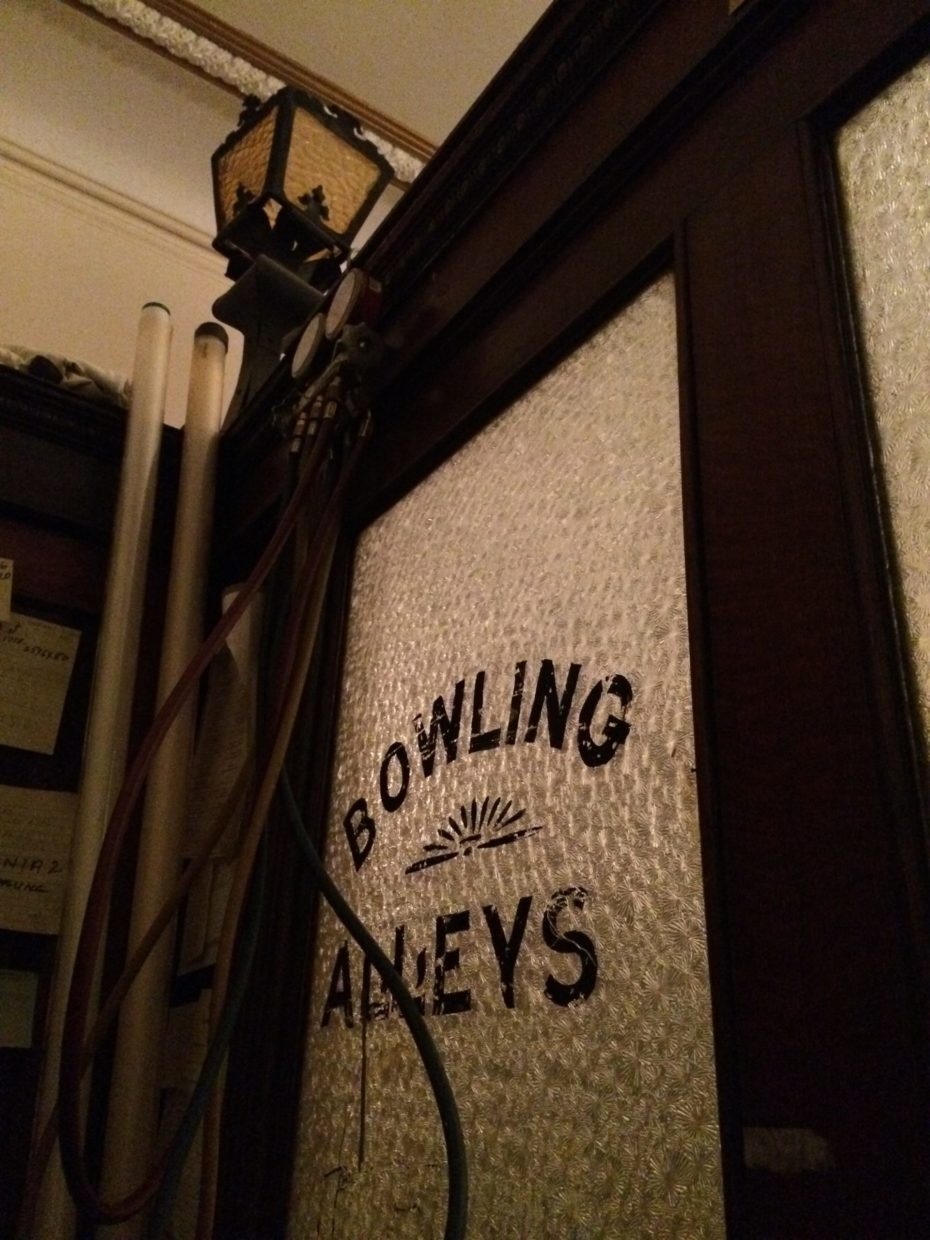

Hiding around Manhattan are some little-known gems that are closed off to the public: from the stunningly ornate City Hall subway station, to the Art Deco apartments hiding above Radio City Music Hall, to the hidden rooftop gardens of Rockefeller Center. But perhaps the champion of them all, is the exquisite bowling alley found in the basement of the Frick Museum.

To the beautiful works of art Henry Clay Frick filled his Upper East Side mansion with, in 1914 the steel magnate added a wonderful bowling alley. Vaulted ceilings, lanes made of pine and maple and a Brunswick-Balke-Collender Company ‘Loop-the-Loop’ ball return system, led Frick to write to the manager of Brunswick’s, praising him for installing “the finest known to the alley builder’s art.”

LYNDHURST

As befitting for one of 19th century America’s richest men, railroad tycoon Jay Gould spent the summers in a suitably imposing Gothic Revival mansion overlooking the Hudson River just south of Tarrytown.

But to the spires, towers and turrets, were added some splendid touches including one of the largest private greenhouses in America and, in 1894, a beautiful bowling alley, installed by his daughter, Helen Gould. A remarkable woman ahead of her time, Helen Gould was one of the first women to graduate from New York University’s Law Program, in 1895, and devoted herself to philanthropic pursuits. She opened a sewing school for local girls in the Bowling Alley building and a cooking school for boys in a former Kennel Building.

Helen Gould was thought to champion bowling as it was one of the few sports both women and men could partake in together, without breaking the social and moral customs of Victorian high society. The alley was built with two lanes, glorious wood panelling, bead board and windows overlooking the Hudson River, surely one of the most beautiful places to bowl strikes and spares.

GRAND PROSPECT HALL

Brooklyn’s beloved, whimsical Victorian banqueting dancehall, equal parts gaudy kitsch and Versailles inspired grandeur is in imminent danger of being torn down. The former opera house may be 129 years old, but the new owners have plans to demolish one of Brooklyn’s most beautiful gems.

Once filled with glittering chandeliers and gilded glitz, heading towards the main bathrooms however, and you’d spy printed on a glass window in peeling old paint the words ‘Bowling Alleys’. Closed off during public events, behind the glass panel is/ was a narrow staircase that leads to a basement and the old bowling alley.

When we ventured down there during a Halloween ball a few years ago, the alley was being used for storage, filled with dusty chandeliers, silverware, and forgotten furniture. But it was still possible to make out the warped wood of the unused bowling lanes, and here and there, the scattered wooden pins, remnants of happier times at one of Brooklyn’s most magical places, that we hope will somehow survive.

GREYSTONE MANSION

The bowling alley in this Tudor Revival mansion in Beverly Hills should be instantly recognisable to connoisseurs of old fashioned bowling and the films of Paul Thomas Anderson alike: it was here that Daniel Day Lewis’ oil tycoon Daniel Plainview bludgeons his son to death with a bowling pin. Although the bowling alley is fairly spartan in appearance, it resembles a 1920s gymnasium, Greystone’s grandeur and location has long made it a favourite with Hollywood location scouts; you’ll find Greystone cropping up in such varied places as Van Halen’s video for Oh Pretty Woman, Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man, the Big Lebowski, and Gilmore Girls.

The mansion however, was no stranger to real life murder and scandal. It was built in 1928 by oil tycoon Edward L. Doheny, who struck black-gold near the La Brea Tar Pits, driving the great California oil boom. One of the richest men in America, Doheny was the inspiration for Upton Sinclair’s novel Oil!, in turn the inspiration for Paul Thomas Anderson’s film There Will Be Blood.

Doheny gave the mansion as a gift to his son, but just a few months after Edward ‘Ned’ Dohney Jr and his family had moved into their luxurious 55 room home, the heir to the oil fortune was found shot to death in a guest bedroom lying next to his secretary Hugh Plunkett in an apparent murder-suicide. The case of the sensational high society killings was swiftly closed, but was thought to be linked to the ‘Teapot Dome Scandal’, where Dohney Sr had been on trial at the time of the killings for attempting to bribe a member of President Warren G. Harding’s cabinet to get a lease on Federal oil reserves, a case that had also involved Ned Dohney Jr and his secretary. The Greystone estate is open to the public by reservation.

FAIR LANE

Henry Ford was at the forefront of technology when it came to mass producing automobiles, and he applied the same ingenuity to the bowling alley installed at his Fair Lane mansion in Dearborn, Michigan.

To the hand laid Brunswick bowling lane, Ford added a mechanism called a ‘Pin Spotter’, which helped line up the pins using metal rods that would emerge from the floor when a lever was pushed, quite the technological marvel for the 1910s. Fair Lane was Henry and Clara Ford’s home for over three decades. Just imagine the man who revolutionised the automobile industry retiring for a few frames with his friends Thomas Edison and Harvey Firestone.

Fair Lane is open to the public and the bowling alley is currently being restored to its former glory.

THE WHITE HOUSE

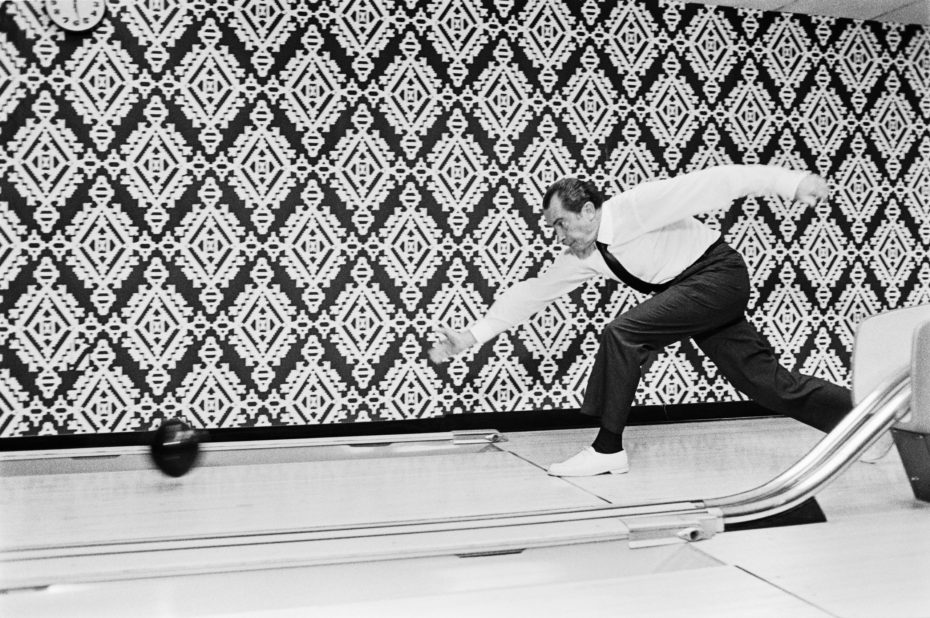

The most prestigious private bowling alley in America is perhaps the hardest to get into. For in the basement underneath the North Portico lies the White House Bowling Alley. Many Presidents sought to relieve the stress of being the leader of the free world, by installing their own ways to unwind. Theodore Roosevelt put in a tennis court, Dwight D. Eisenhower a putting green, whilst FDR added an indoor swimming pool. In 1947, President Harry S. Truman installed the White House’s first bowling alley, a relatively simple two lane affair in the West Wing.

Truman favoured playing poker to bowling, but the lanes were well used by White House staff, even hosting a league comprised of Secret Service agents. President Nixon and First Lady Pat were much keener bowlers and they built a new one lane alley in the basement, which is still in use today, and hopefully the only place the President of United States will ever launch a pre-emptive strike.

THE OLD HOBOKEN REPUBLICAN CLUB

Private bowling alleys weren’t solely enjoyed by the wealthy elite. Throughout the US, the professional middle classes often installed bowling alleys in all manner of institutions and private clubs. Churches are often hiding some incredible alleys in their basements. Wood worker Anton David was recently working on renovating and outfitting a new optometrists store in downtown Hoboken, when he made an incredible discovery in the basement of the old brick townhouse: an historic, old wooden bowling alley.

“Working in the basement,” he explains, “I saw what looked like some unnecessary framing. Lifting the old floor, a flashlight showed really nice wood, bowling pins and even some old beer cans,” alongside the remnants of decaying bowling lanes. At the back of the bowling lane was a leather bounce board used to absorb the impact of the bowling balls. The board was traced to another old Hoboken company, Newman Leather, who once made saddles during the Civil War. Further research by the Hoboken Historical Museum showed that a century ago, the building was the home of the Hoboken Republican Club, and later the Hoboken Democratic Club.

It was highly fortunate that the discoverer of the old lanes hidden in the basement, was an expert in woodwork Today, Anton David has restored the lanes to a beautiful, gleaming condition, much as they were a century ago, when the local politicians of Hoboken sought to unwind from their daily toil and enjoy a few frames and beers in the basement.

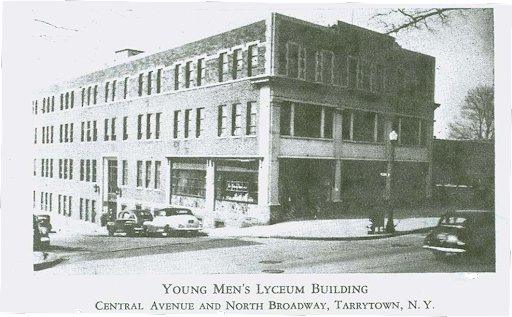

THE YOUNG MEN’S LYCEUM CLUB OF TARRYTOWN

You could once find Lyceum Clubs in towns and cities all over America. They flourished in the 19th century as places to encourage adult education during an era when graduating high school and further college education was a rarity. Lyceum Clubs offered lectures, well-stocked libraries, concerts and visiting speakers, all with the aim to improve the intellectual and moral fabric of the members. They also placed an emphasis on sporting activities, fielding local baseball teams, organising cycling clubs, installing gymnasiums and sometimes, bowling alleys. The Lyceums swiftly became vibrant social clubs, where the professional class of the town, businessmen, teachers, lawyers and the like could meet after work. Incredibly, one such clubhouse is still up and running in Tarrytown, New York, the village made famous by Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. Venture downstairs and you’ll discover a wonderful surviving private members clubhouse from a time where as they put it themselves, “life moved at a slower pace. Men would come in, grab a book from the library and read as they sat by the fireplace, smoking their pipes.”

To compliment the splendid Victorian library of some 1,400 books, fireplace and club chairs, there is also a marvellous old four lane bowling alley, where in April, 2008, club member Steve Ivkosic bowled one of the more elusive feats in sport: a perfect ‘300’ game, twelve bowls, all of them strikes. “We looked through the record books and it doesn’t seem as though it ever happened here before,” says former President Tom Basher. “It was absolutely exhilarating to see someone finally conquer these impossible lanes.”

The Young Men’s Lyceum Club of Tarrytown established in 1866, has remained true to its roots: it might be one of the few places in New York that is still for better or worse, “a social club, exclusive to men, that allows smoking, doesn’t fit in modern society.” But it still thrives, thanks to the work and enthusiasm of its members. The Lyceum dates from a time when the sporting equipment on offer was still lovingly handmade and crafted in America; the American Shuffleboard Company of Union New Jersey and H.Wagner & Adler Company of New York who made the ‘Highskore Cushions’ billiard table, and the beautiful wooden ‘ABC Regulation’ bowling alley. It’s a place where Lincoln’s birthday is still celebrated with an annual dinner, and where visitors are greeted with a friendly hand shake and an offer of a cold beer.

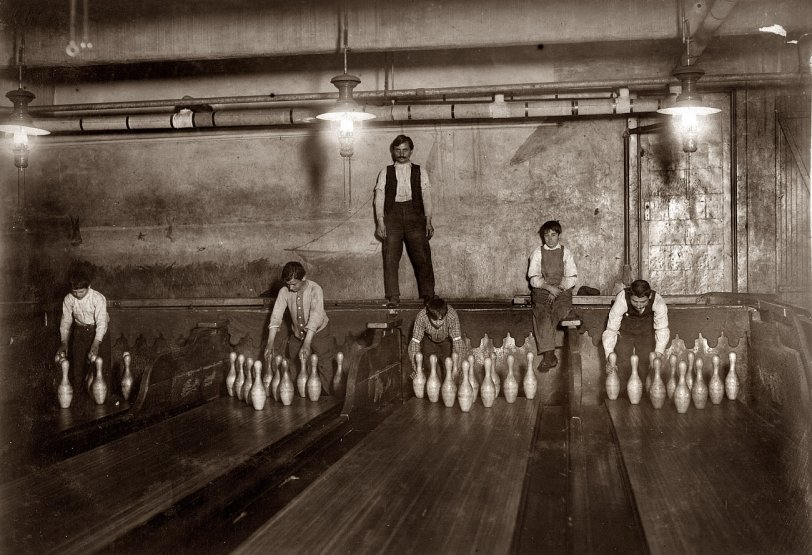

LIFE AS A PINBOY

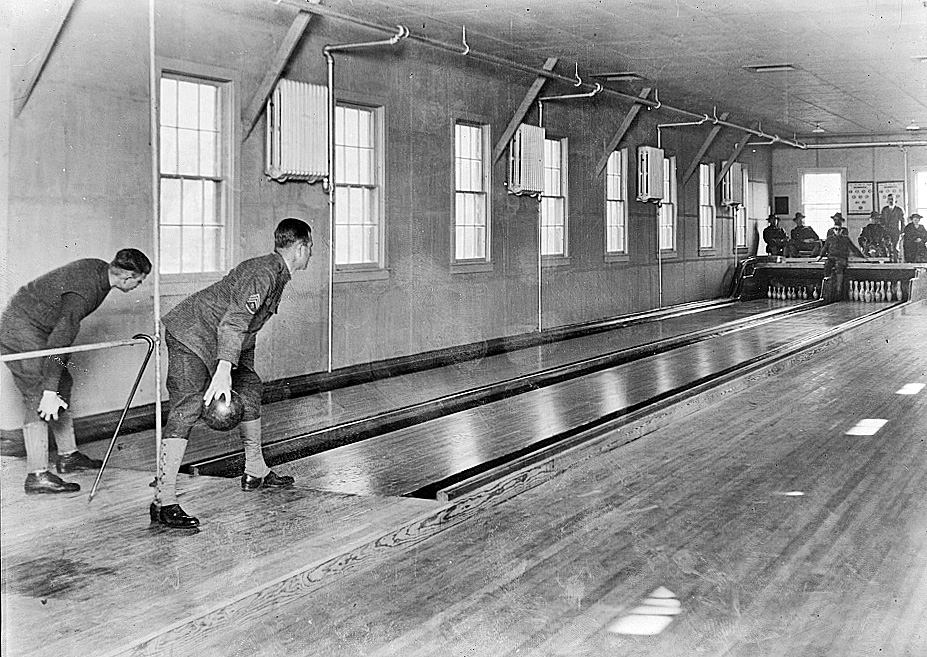

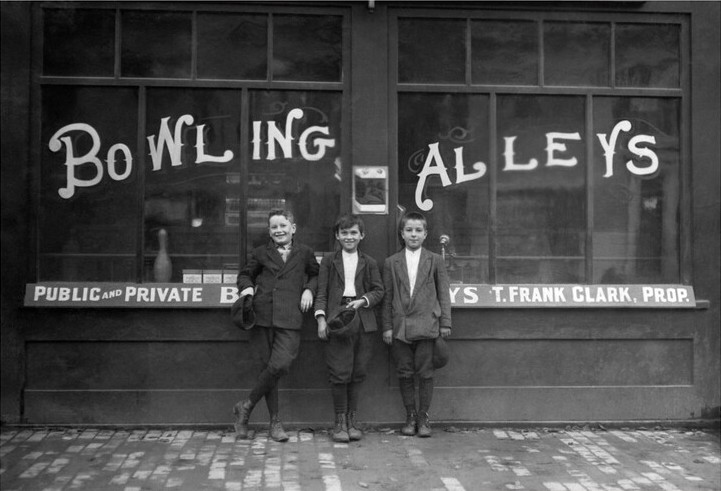

One of the most colourful aspects of old fashioned bowling was the employment of manual pinsetters, usually teenagers known as ‘Pin boys’ or ‘Pin monkeys’.

Before Gottfried Schmidt invented the mechanical pinsetter in 1936, the resetting of fallen pins and the returning of bowled balls was all done by hand. One of the lost jobs of yesteryear, Pin boys would be stationed behind the pins usually in a sunken area, or perched on a ledge, ready to manually reset the game.

If you weren’t fortunate enough to be a Pin boy at the Frick or Fair Lane, that usually meant working at a saloon or a small town alley, exposed to hard drinking, smoking and late nights, all for a few dollars a night. “I had broken ribs from getting hit with pins, smashed fingers, and of course, your shins were always banged up,” remembers Gary Helfrich, who set pins in the bars of Buffalo, NY for 11 cents a game. “You had to watch for the wise guys who threw the balls 100 miles an hour just to see if they could make the pins fly.”

Rob Yasinac, explorer and photographer from Hudson Valley Ruins, worked as a pinsetter at the Tarrytown Lyceum Club in the early 1990s. “The alley had four lanes and we went back and forth between setting pins in two lanes each,” explains Yasinac. “The bowlers were very serious. We had to be careful not to send the balls back down the return track too hard – the guys didn’t like it, of course, if their bowling balls went off the track. I might’ve made that offence once! And we had to pay attention to the games in each lane to know when pins needed to be reset or not – sometimes, it seemed, they wanted the pins cleared/reset even if they only bowled once. We got paid good money. I don’t recall exactly – it was either 20 dollars or 30 dollars per night – but either way it was good money for two hours’ work, 30 years ago! I enjoyed it. It was straight-forward work, for the most part, and not physically-demanding. And it was a cool place to be in and to do the kind of work that was non-existent every where else.”

Other tavern bowling alleys were far less genteel than the Lyceum Club. As photographer Kevin Hong explains, “Pin boys were rough characters. They were paid the barest wages and many were street toughs – kids picked up from Skid Row. It was difficult, physical labor. The bowling alley did not have a great reputation as a wholesome place for families. The invention of the pinsetter eliminated the pin boy and made bowling available at all hours, all the time. It helped to clean up the image.”

The arrival of mechanical pin setting helped spur the popularity of bowling in the 1950s and 60s. “Bowling became a wonderful, wholesome recreation that families with young children could experience together. Families could bowl together, kids could join youth leagues, the moms could go bowl with other housewives, and ‘the guys’ could get together for a league night, out of the house.”

These are just a tiny selection of the old fashioned, wooden bowling alleys that have survived. Whilst some are well known, who knows how many are lying hidden and forgotten in the basement of an abandoned mansion or small town saloon. Kevin Hong remains dedicated to tracking them all down. “Since 2012, I’ve officially been to about 102 places for my project,” he explains. “The oldest place was built in the 1860s, in a basement in St. Charles, Missouri. I loved the lanes at Scott’s Oquaga Lake House in New York, where they filmed the Marvellous Mrs. Maisel, but that resort closed. You just don’t see old-school lanes that much anymore.”