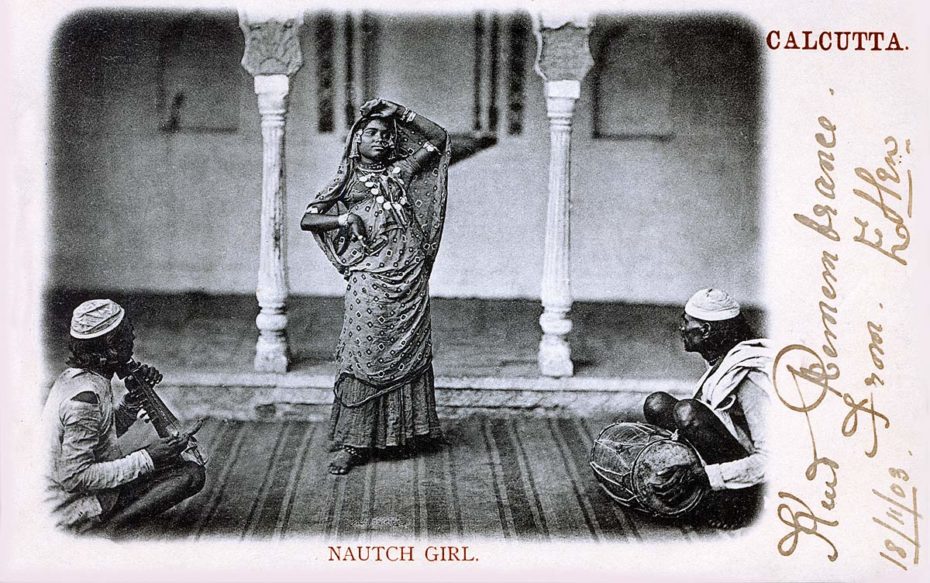

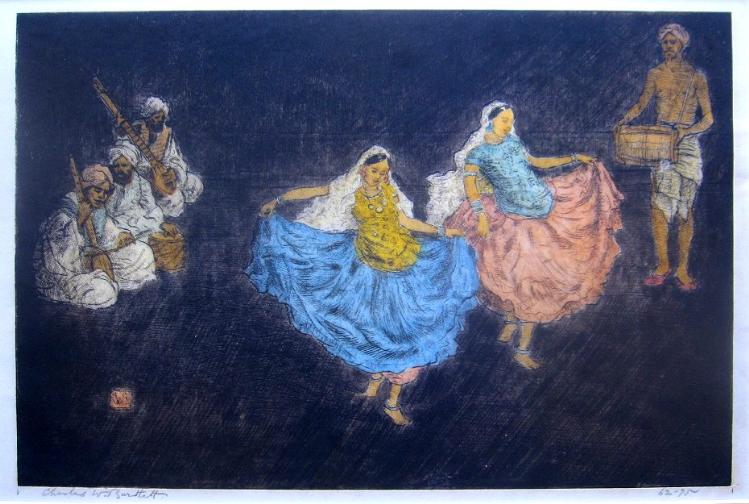

You arrive at the gardens after nightfall with the full moon casting a cool, pale glow over the muggy evening. Two dozen torch bearers stand by to light your way, and as you approach the crowd, you sense the anxious anticipation of the delights to come. Soon the musicians strike up their instruments, and a group of gazelle-eyed dancers draped in sky blue and crimson seem to float into the midst of the party on delicate, nimble steps. A torch bearer steps forward, holding the light first to a dancer’s face and then lower down, throwing dazzling sparkles from the gold tinsel embroidery of her robes and showing off her charms to best advantage. The guests, Indian and British alike, stand entranced by the graceful twisting of hands and expressive glances. The entertainments continue until the sunrise peeks over the horizon, but even that blaze of pink and orange light seems lacking after the enchantments of the nautch party. The “nautch girls” of India were revered for their artistic talents until they were reviled for their supposed licentiousness; before their name was reduced to another euphemism for sex worker in the colonial Far East.

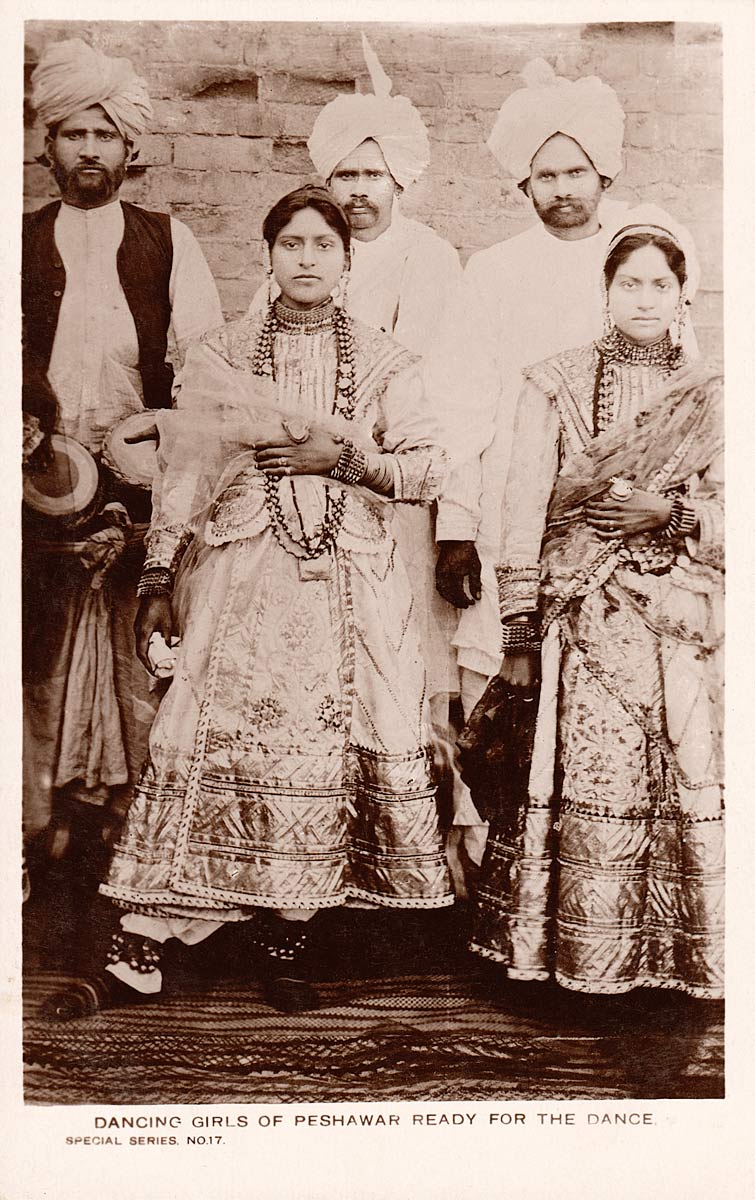

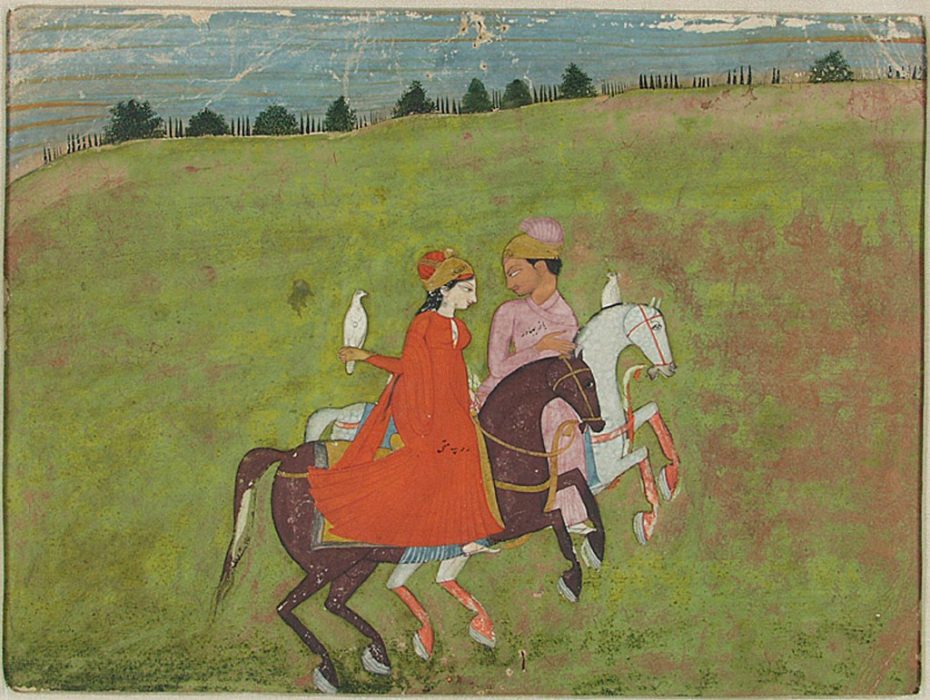

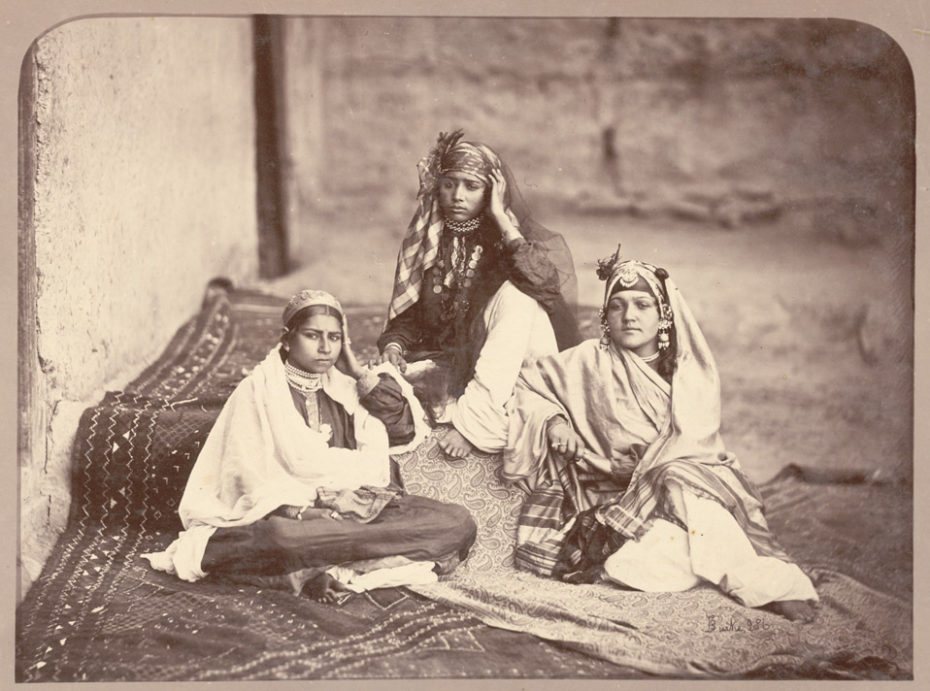

If we look past the glittering embroidery, we find a complex cultural institution evolved over centuries from multiple traditions, indelibly changed and eventually erased by colonial rule. While dance as a profession in India can be traced back to before the common era through poetry and epics, the rise of the Devadasi or Hindu temple dancer in Southern India heightened the social status of dance during the 6th and 7th centuries. Dedicated to a temple before puberty and considered married to a deity for life, the Devadasi played an essential role in worship through dance and song while also attending to the temple, lighting the lamps and dressing the deities. The Devadasis’ skilled artistry and religious devotion meant they were respected members of society who played an important role in the community. During the Mughal empire however (1526-1857), dance increasingly moved from an act of religious worship to a form of public entertainment. Central to court life in North India was the tawaif, a courtesan skilled in dance, music, poetry and literature. Tawaifs were so respected for their taste and refinement that they were responsible for educating young future nawabs or rulers on the finer points of art, music and writing. Like the geisha of Japan and the Ouled Nail of Algeria, the tawaif’s primary role was that of accomplished artist and entertainer. While she might engage in sex with her patrons incidentally, it was never a foregone conclusion or a specific service for which one might pay. Tawaifs served royalty and the elite, but the popularity of dance entertainment grew beyond palace walls to the common people as well.

Some beloved dancers from the Mughal period slipped into immortality as legends and folk tales, but none have endured with such a lasting impact as Rani Rupmati. Her talents as a singer and dancer earned her the attention of Baz Bahadur, ruler of Malwa. Immediately charmed, for Rupmati was said to be “more beautiful than the moon, the tulip and early dawn of the spring,” Baz Bahadur took her into his harem, and the two fell passionately in love. But the jealous Emperor Akbar wanted her for his own and invaded Malwa with a host of soldiers. Baz Bahadur was no match for this military might, but Rupmati refused to have her love and her agency taken from her, poisoning herself by drinking diamond powder and dying a martyr.

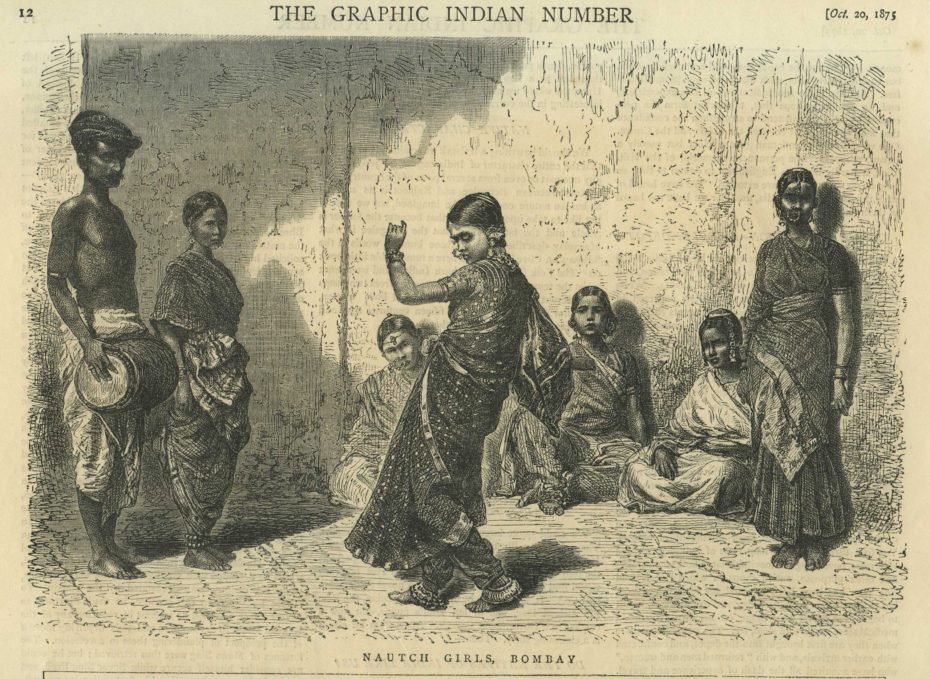

Into this world where dance fulfilled multiple societal roles across regions and social classes came the British. European colonizers weren’t known for their ability to distinguish the subtleties of public and artistic roles of women in cultures outside their own (see again the treatment of the geisha and the Ouled Nail). The word “nautch” in fact is an Anglicanized version of the Hindi/Urdu word “nach” meaning dance, and the term “nautch girl” came to consolidate various types of dancers under one generic umbrella imbued with a hint of the forbidden. So while professional dancers certainly existed for thousands of years before the British arrived, the nautch girl as a broad category is a curious intersection of Indian culture and British colonialism.

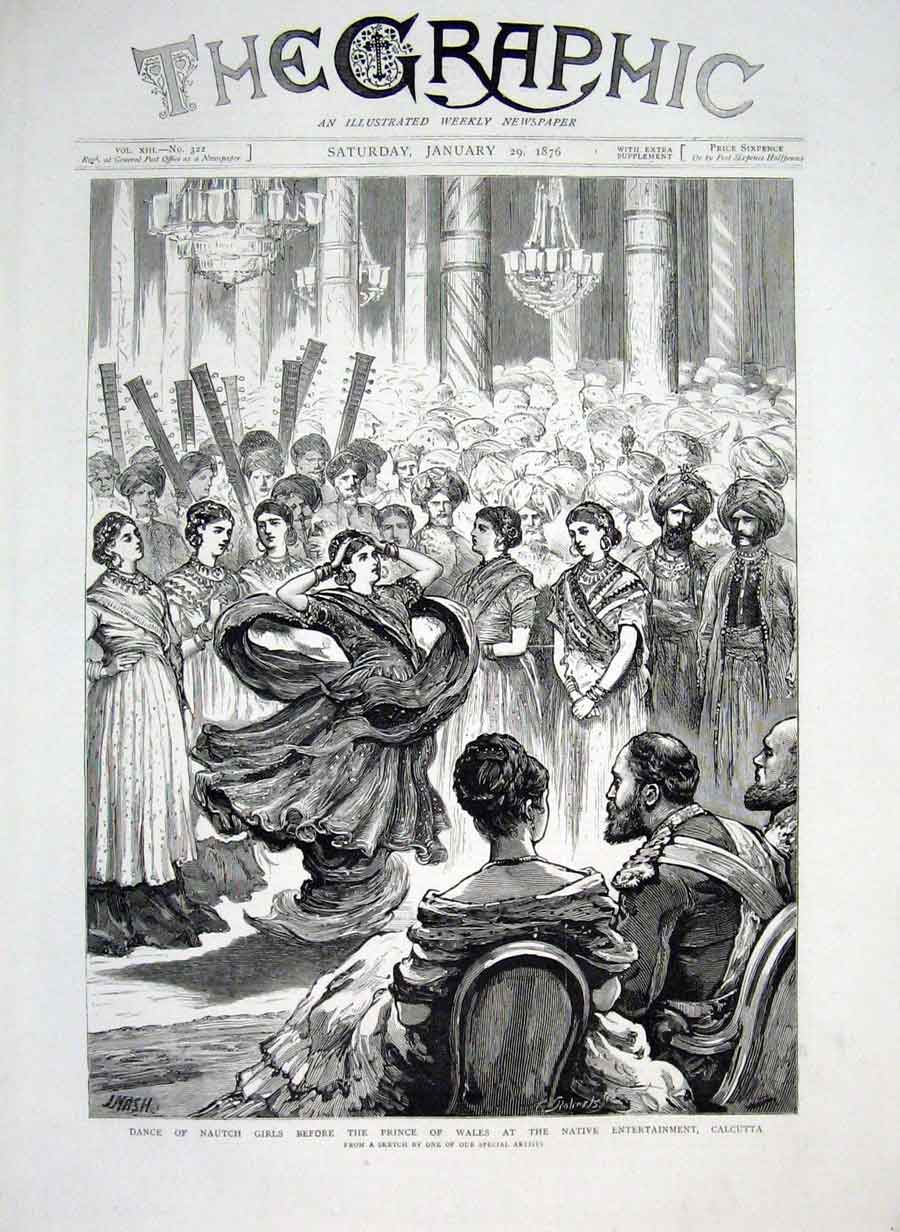

Still, in the early years of British occupation nautch performers were not only sought after and patronized by the colonizers but generally respected as well. One travelogue described the nautch girls’ alluring performances as “superior to all the operas in the world.” In his 1813 Oriental Memoirs, James Forbes said of the nautch, “They are extremely delicate in their person, soft and regular in their features, with a form of perfect symmetry, and although dedicated from infancy to this profession, they in general preserve a decency and modesty in their demeanour, which is more likely to allure than the shameless effrontery of similar characters in other countries.” When the Prince of Wales Albert Edward toured India in 1875-76, he was feted at a nautch party to much acclaim.

The dances retained their regional flavor and histories despite being lumped into the same category: dassi attam temple dances of the Devadasi in the south and storytelling kathak dances of the tawaif tradition in the north. Songs both in Hindi and Persian were popular and often spoke of romantic yearning or the adventurous love lives of the gods. The kite dance was particularly highly regarded, in which the dancers emulated the movements both of a kite and of a kite flier, full of grace and suppleness.

Impressed by the wealth and sophistication they found in India, the early English settlers sought to emulate the lavish lifestyles of native princes. And nothing indicated cash and class quite like having your own entourage of dancing girls and musicians at your disposal to welcome and entertain your guests. Even among the rank and file of the British army, who didn’t necessarily get rich quick off exploiting the subcontinent’s resources like their superiors, nautch parties were an obsession, and men would pool their resources to hire a troupe of dancers for an evening. Soldiers became such reliable patrons that bands of nautch girls followed the army as it moved across India.

The truth was the invaders arrived initially without British women, so these lonely men far from home relished the company and presence of accomplished and attractive local women. But as missionaries settled on the subcontinent and as travel became easier and more British women arrived, the sentiment shifted. The trappings and entertainments of life in England were increasingly available in India, so though the “sahibs” had embraced local culture before, they gravitated back to the familiarity of their own traditions as those opportunities presented themselves. At the same time, a powerful anti-nautch movement arose, driven by a seemingly unlikely alliance: Christian missionaries and middle-class Indian social reformers.

Missionary schools created a class of Indians raised with a specific set of Victorian British morals and intentionally alienated from their own customs. As British reformers denounced Indian religious traditions as heathen and Indian culture as barbarous, some English-educated Indians internalized the message and condemned their own social heritage in a bid to reform India into something more “civilized” according to Western values. And at the very top of the list of targets to be destroyed were the nautch girls.

Beginning in Madras then spreading throughout the country, Hindu social reform and purity societies enumerated the evils of nautch girls in pamphlets and newspaper articles: they impoverished their patrons, caused bodily weakness and spread diseases. Similar messages were aimed at the British, with English women encouraged never to attend nautch parties and to prevent their husbands from doing so lest they fall into ruin. Reformer Keshub Chandra Sen said of the nautch girl, “In her breast is a vast ocean of poison. Round her comely waist dwell the furies of hell. Her hands are brandishing unseen daggers ever ready to strike unwary or wilful victims that fall in her way. Her blandishments are India’s ruin. Alas; her smile is India’s death.” These attacks were carefully aimed– it was not the dance and music that were denigrated by the reformers but the dancers themselves.

Despite appeals by these reformers to outlaw nautch parties, the British governors initially resisted, seeing nothing improper in the performances. But the reformers pressed on, enlisting the press and imploring Europeans to take up their cause; they were, after all, championing Western ideals. The campaign was relentless from the 1890s onward. The dancers fought back, with the Madras Devadasi Association issuing a statement comparing their vocation to Buddhist and Catholic nuns, highlighting their rich literary and religious heritage and calling for more access to education so they “will occupy once again the same rank which we held in the national life of the past.” But the wave of anti-nautch sentiment could not be turned back. When Prince George of Wales visited Madras in 1905, reformers won a huge victory in canceling the nautch party planned to celebrate his arrival, despite the fact that his predecessor had attended just such a performance 30 years earlier.

As they lost their favor and their patrons, many nautch girls were forced to either prove their respectability by marrying and giving up their profession or find other ways to survive. Many turned to prostitution, finally becoming the sex workers some always assumed they had been. The gilded nautch parties of yesteryear faded, though nautch girls continued to hold some allure even into the 30s as you can see from this newsreel. After India gained independence the Devadasi system was outlawed. In some areas the practice continues illegally in a diminished form in which women and girls are at high risk of sexual abuse and trafficking. The pleasures of the all-night nautch party may be lost to history, the spellbinding nature of India’s dance heritage lives on in the mesmerizing glamour of Bollywood.