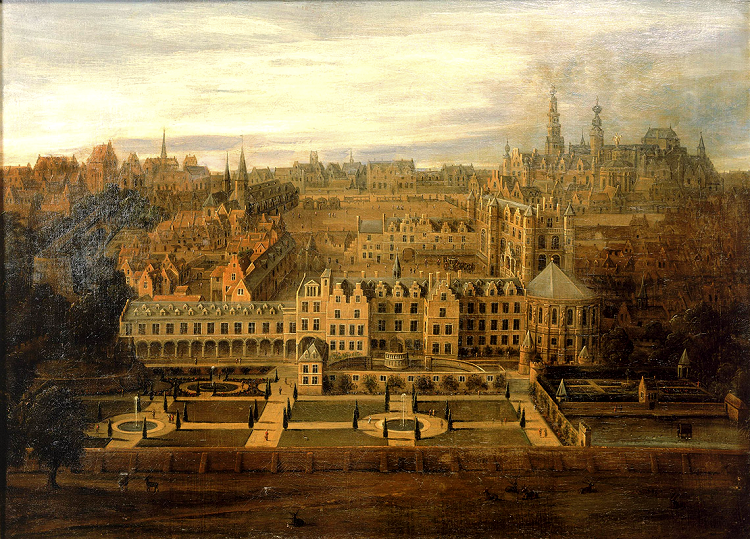

Coudenberg Palace was once the envy of all of Europe. It had everything you could want in an opulent royal residence; a monstrous banqueting hall that dazzled guests with its sublime décor, sumptuous apartments filled with works by important artists like Rubens, and extensive grounds and gardens where ladies and gentleman of the court could promenade in their latest fashions. For 700 hundred years, it ruled over Brussels as the seat of the government from a small hill in the city centre. That small hill is now the Place Royale, and when tourists come to gaze at the impressive neo-classical buildings that border the square in the heart of Brussels, it’s a pretty safe bet that not many of them know that they are in fact standing on the remains of Belgium’s forgotten Versailles.

The name itself, “Coudenberg” originated from the Dutch for cold hill, certainly deriving from the fact that the original structure was built on what was once medieval Brussel’s highest hill. The location was at first chosen for strategic reasons, built in the 12th century in order to defend its territory. As the city of Brussels developed, it came to rival the Leuven, which had previously been the seat of the court. And so in the 13th century, the Dukes of Brabant rebranded the city of Brussels, boosting its political appeal and putting it on the map for the European influencers of the day. By the following century, Coudenberg Palace had become the palace-to-be for the rich and famous, providing the perfect venue to host diplomats and royalty of the highest caliber.

The power balance was once again knocked off-kilter in the 15th century and Brussels scrambled to attract Europe’s new powerhouses, prompting Duke Philip the Good to order the extension of the palace, building the Aula Magna, an over the top banqueting hall that would put the palace back on the European map. It was host to regular meetings between delegates, clergy and nobility of the Burgundian Netherlands, and Coudenberg became the seat of the central administration for the Low Countries consisting of what is now Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and parts of France and Germany.

When the most powerful Western emperor, Charles V, took control he chose to further extend the palace, introducing a substantial chapel built in the Gothic style in the 16th century and generally adding to the impressive nature of the architecture. As the influence of the Coudenberg Palace continued to expand, nobility chose to build their residences close by, further developing the city and adding greater levels of prestige.

Charles V was the last remaining monarch to stay at Coudenberg, abdicating the throne to his son Philip II. Those who followed chose not to live in the Brussels palace but instead, rule from from Madrid or Vienna. And so Coudenberg played host to a number of different governors, including, Charles V’s sister. Handing over control of the palace however, might not have been the best idea for Coudenberg, as it was at the hands of one such Governor-General that it met its untimely demise.

It’s a cold winter’s night in February of 1731, and sister to the Emperor Charles VI, Archduchess Maria-Elisabeth of Austria is finally able to retire to her rooms after an exhausting day. Perhaps overcome with fatigue she fails to extinguish the candles in her room, provoking a fire to break out that rapidly spreads throughout the palace. As the fire consumes the royal palace, the firefighters are met with an unfortunate conundrum. Protocol dictates that they are forbidden from entering the governor’s private apartments, meaning that they are not able to get to the source of the blaze, or save the now trapped Maria-Elisabeth. With icy conditions and wind hampering their efforts further, the fire is able to quickly engulf Coudenberg, and efforts to get water into the palace are slow and fruitless. One firefighter chooses to defy royal protocol and bursts through to Maria-Elisabeth’s room, saving her from the hungry flames.

In the official report of the fire, those involved were clearly far too afraid to place any blame on the Archduchess as the culprit of the fire, pointing the finger instead at the kitchen staff and the “carelessness of the kitchen chefs who were boiling sugar to make jam”.

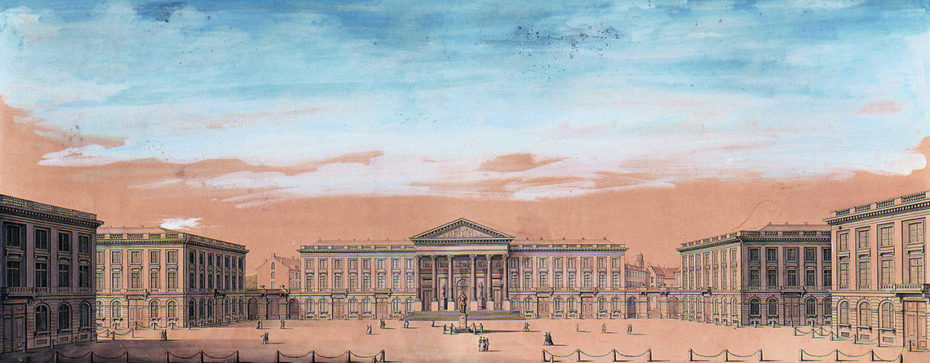

Following the fire, the court decamped into the neighbouring Nassau House, leaving behind Coudenberg which had now been renamed the Burnt Palace. The cindered remains of Coudenberg would sit untouched for 40 years until the Empress Maria Theresa of Austria gave permission to knock it down and replace the entire site with a public square.

The introduction of the neo-classical buildings that surrounded Place Royal revolutionised the city of Brussels, ushering in a new style of architecture which helped shape the city into what it is today. Even the hill on which the palace once stood was flattened, effectively erasing any trace of Coudenberg.

Left out of history books, gone from public consciousness, for many years historians and archaeologists were uninterested in the remains of the palace. Only in the 1980s did people once again start to become aware of its existence and the first archaeological searches were carried out. A 25 year period of excavations followed, which led to the rediscovery of Coudenberg, its buried structure and many hidden artefacts, most coming from the once magnificent Aula Magna.

Parts of the Coudenberg still remained intact under the Place Royale, 300 years later, and upon completion of excavations, the archaeological vestiges of the palace and its foundations have finally been unveiled and opened to the public. Hidden away beneath the feet of those that come to marvel at the neo-classical buildings on display, the ghost of a once great palace awaits….