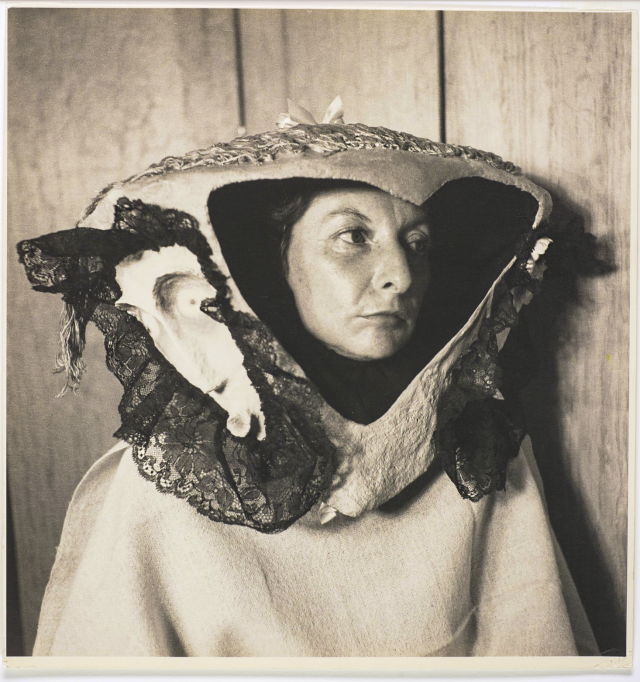

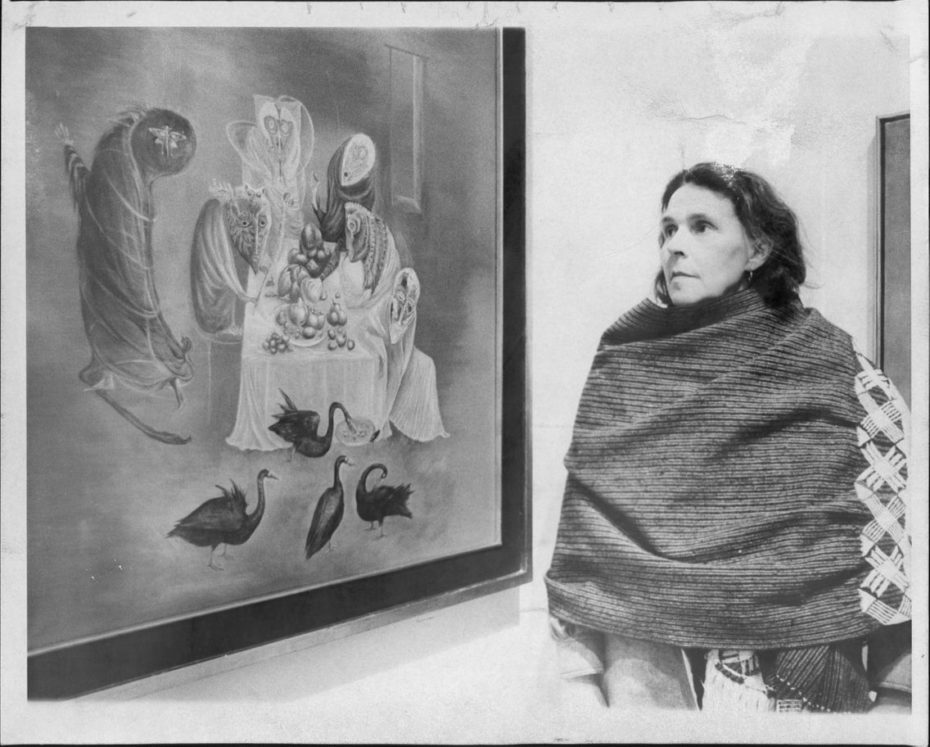

On paper, she is Britain’s lost surrealist; an English debutante who cut herself off from her wealthy family, fell in love with Max Ernst and eloped with him to Paris, finding herself in the centre of surrealist movement. Separated from Ernst by war, she later ended up in Mexico, and became one of the country’s most famous adopted artists, as well as a founding member of the women’s liberation movement in Mexico during the 1970s. But the thing that struck me first and foremost about trying to piece together Leonora Carrington’s mysterious life story is that it’s not unlike trying to grasp the size of the universe, the speed of light or the concept of time. As soon as you think you’ve figured out a piece of it, you realise with trepidation, it’s too vast to fully get your head around. “I am as mysterious to myself as I am to others”, she once said. That she was. Genius painter, sculptor and writer. Sanguine lover, mother, friend and mentor. Sage, alchemist, psychic, mystic and shaman. Rebel, pioneer and feminist. A battle-hardy yet vulnerable woman who was as painfully aware of her own inner demons as she was of the external ones facing women as a tribe.

Leonora Carrington was born at a stately home in Lancashire, England in 1917, born into a privileged but repressive background. She was expelled from schools for being rebellious and sent to finishing schools to improve her prospects. A “beautiful, sparky young woman with her dark eyes, crimson lips, and cascade of raven curls”, a picture painted by her biographer Joanna Moorhead, as a teenage debutante, Leonora, snubbed the powers that be when expected to make her society debut. She opted instead to bury her nose in Aldous Huxley’s Eyeless in Gaza (1936), an account of socialite Anthony Beavis’ disillusionment with high society and his pursuit of mysticism and meaning in his life.

Leonora’s lifelong liaison with surrealism started early: at the age of 10, when she spotted her first surrealist painting in the window of a gallery and did a double take. This flashbulb moment profoundly shaped her life; she no doubt saw something inexplicably visceral and longed to be an artist. A decade on, armed with a gift from her mother in 1936, Herbert Read’s book Surrealism, she kept forging a route that was a natural fit for her fiercely intuitive feminist mind. Her well-to-do Lancashire family connections provided academic credibility and saw her attend the Chelsea School of Art and Ozenfant Academy of Fine Arts in London, but Leonora wasn’t shy about expressing her distaste for her privileged upper-class upbringing. Her 1937 short story, The Debutante, written in 1937, was a precursor of the bizarre black humour she was to display throughout her life. It starts like this, “The beast I knew best was a young hyena…”, a tale in which a girl meets a hyena at the zoo and convinces the hyena to take her place at a dreaded ball. The hyena agrees, kills and eats the maid – bar her face (which was neatly nibbled around but left intact as a disguise). The pair almost pulls off the stunt, but at the end of the evening the hyena can’t resist eating the maid’s face too, exposing the crime.

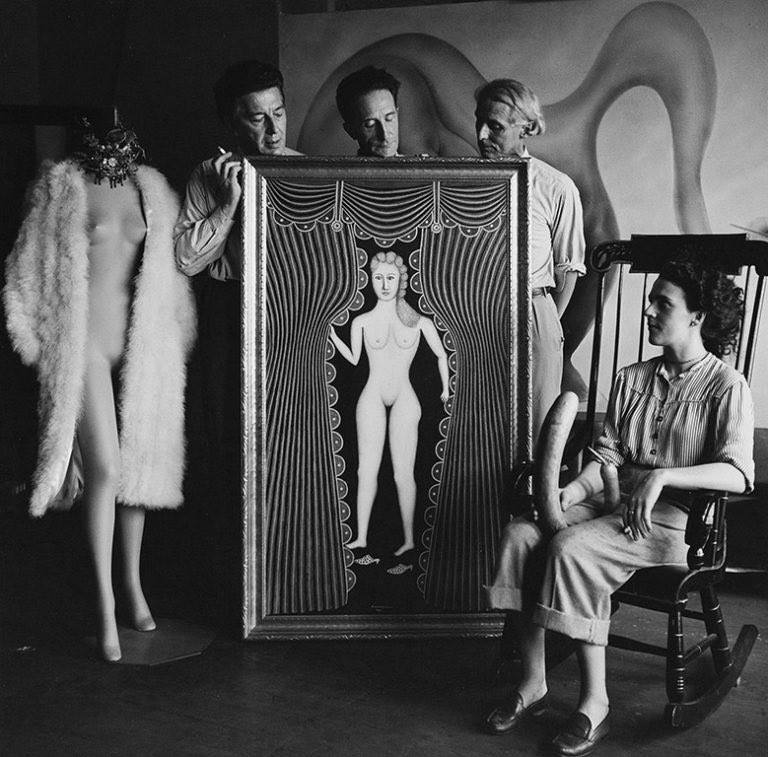

Her crush on German surrealist painter and womanizer Max Ernst started before she had the opportunity to meet him. The stars aligned and when the pair met in the flesh in 1937 in London, Ernst promptly left his wife for Leonora and eloped with her to France. There, she and her mature lover (he was 26 years her senior) had a symbiotic but strangely ambivalent domestic and artistic relationship. They fed off each other for inspiration, decorated their home with their ‘guardian animal’ sculptures – the likes of fish and lizards, women who turned into horses, mermaids and a red unicorn – and even created portraits of one another.

Just after Leonora met Ernst, she began working on Self Portrait, (1937/8), a brutally pragmatic holding up of the mirror to her own sexuality. Like much of her work, it’s full of autobiographical detail, Celtic mythology (her Irish nanny and mother) and plenty magic. Throughout her life she would identify with white horses (her animal self, her alter ego and a symbol of freedom), just like she did with hyenas. She was quoted as saying, “I’m like a hyena, I get into the garbage cans. I have an insatiable curiosity.” Impressively, a year later, Self Portrait rubbed shoulders with Picasso, Dali, Ernst, Miro and Man Ray at The Exposition of Surrealism in Paris, viewed by 6000 visitors in the first week.

When World War II broke out, Max Ernst was arrested by the French but discharged a few weeks later with the help of friends in high places – notably French Surrealist poet Paul Éluard and American journalist Varian Fry (who helped thousands of anti-Nazi and Jewish refugees to escape Nazi Germany). This reprieve was short-lived as Ernst was arrested by the Gestapo. He escaped to the USA with the help of Peggy Guggenheim, leaving a devastated Leonora behind.

A traumatized and inconsolable Leonora left for Madrid with a friend, surrealist artist Catherine Yarrow, but her mental health deteriorated such that she was admitted to an asylum and received electroconvulsive therapy and powerful drugs to alleviate her anxiety and delusions. French writer and poet, co-founder and principal theorist of Surrealism, André Breton would later prompt Leonora to pen the experience of her nervous breakdown and her time in the asylum. Her memoir Down Below describes the dehumanizing treatment and trauma of being institutionalized and sexually assaulted, of anti-psychotic drugs and the altogether unsavoury conditions she was exposed to. Her Portrait of Dr Morales and Map of Down Below were created to illustrate the trauma of her time in the asylum.

When she got out of that asylum, she found herself alone again in Madrid and still heartbroken from her separation with Ernst, when she ran into Mexican ambassador and poet Renato Leduc in a restaurant. The art world at the time was incestuously connected, and it turns out Leduc was an old friend of Pablo Picasso’s. A sympathetic Leduc married Leonora (and divorced her again in 1943) offering her diplomatic immunity and an escape from the war in Europe.

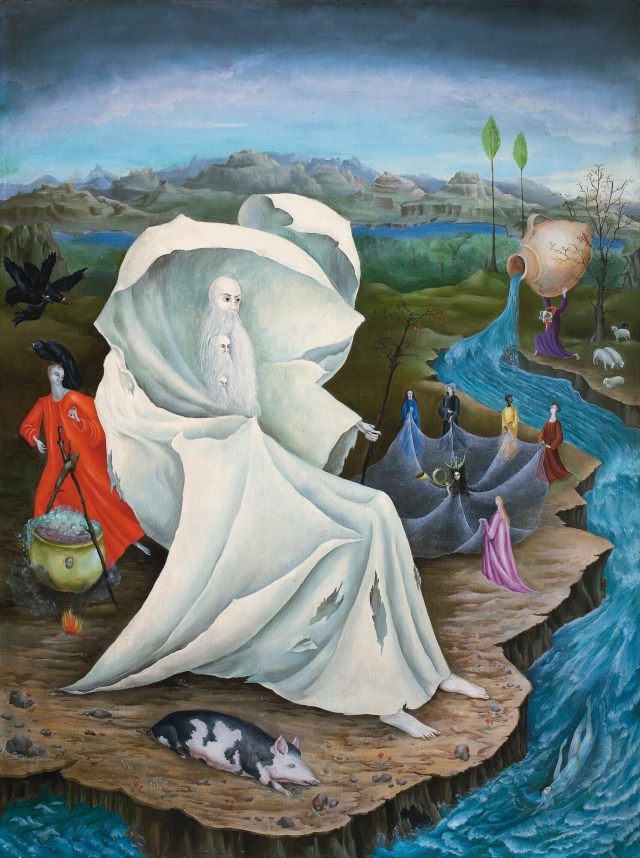

Ernst had by that time married his patron-rescuer Peggy Guggenheim, but this marriage also ended in divorce a few years later. Leonora spent a year in New York and reconnected with Ernst during that stay, although they never resumed their romantic relationship again. But it was her voyage with Leduc to Mexico that fundamentally changed the course of her life and art. André Breton had spent time in Mexico in the 1930s and called it the most surreal place in the world. Despite being so foreign to this Lancashire-raised debutante, at the same time, as an artist, it was a landscape that couldn’t have been more suited to her. There, she worked together with a handful of likeminded women emigres from Europe, notably the Spanish painter Remedios Varo and the Hungarian photographer Kati Horna, not so quietly concocting their very own brand of surrealism in the 40s and 50s.

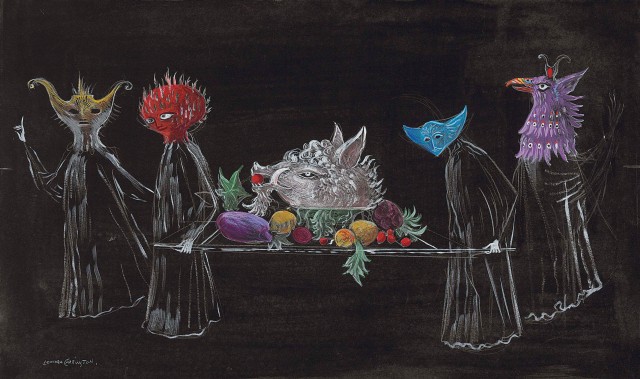

The three expat women had a riotous time together, spurred on by Leonora’s Kafka-esque sense of humour. Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo and Kati Horna fed off each other’s imagination and indulged in curiously surreal and outrageously mischievous social activities like inviting random strangers from the telephone directory to dinner to see what would happen. They would experiment with weird and wonderful recipes like omelettes made from human hair and caviar created from dyed tapioca for their unsuspecting guests.

Leonora married her second husband, Hungarian-born photographer Emericao (‘Chiki’) Weisz, with whom she had two sons. Interestingly enough all three these fiercely independent emigre women deliberately – or so it seems – chose Mexican partners who didn’t compete with them in their creative quests, but instead loyally supported them.

In her adopted Mexico Leonora Carrington was fully regarded as one of their own, and a great honour came her way when she was asked to paint a mural for Mexico’s National Museum of Anthropology. She created The Magical World of the Mayans (Magico de los Mayas) in 1964, a complex tapestry and epic fusion of Christian and pagan history.

The seventies arrived with its liberal and progressive women’s movements including feminism. Leonora responded with her iconic 1972 poster for Women’s Awareness (Mujeres Conciencia), affirming her feminist stance on environmental issues, stating in her nonchalant way: “If all the women of the world decide to control the population, to refuse war, to refuse discrimination of sex or race and thus force men to allow life to survive on this planet, that would be a miracle indeed.” More than a decade later (1986) she would be awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award at the Women’s Caucus for Art convention in New York for her unwavering political efforts in the emancipation of women.

As for the prolific body of work she created, the feminist theme was the backbone that held together all the different strands of her creative endeavours. She spoke up for women at every given opportunity and wrote one of the first books on gender identity. She was also exploring magical realism, a Latin-American strategy of using folk tales, fantasy and myth to depict the real world.

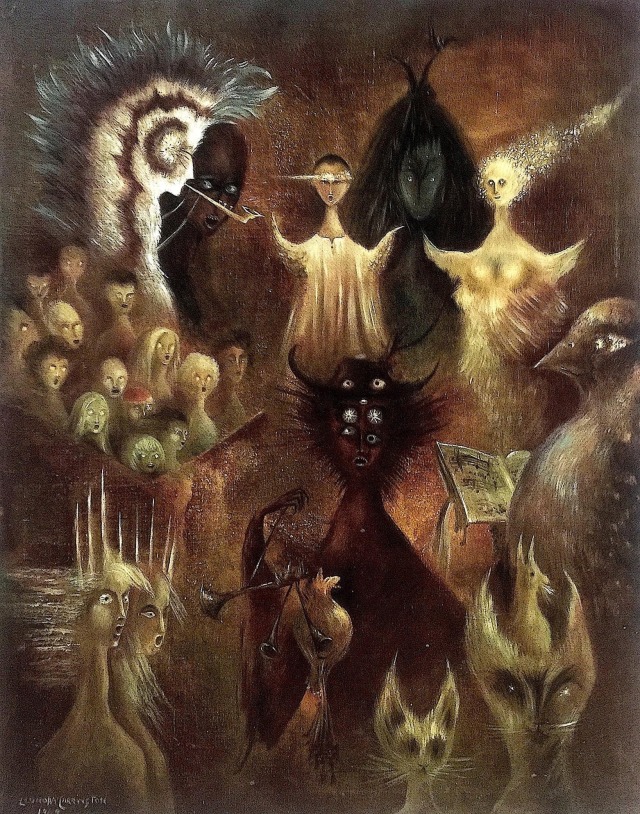

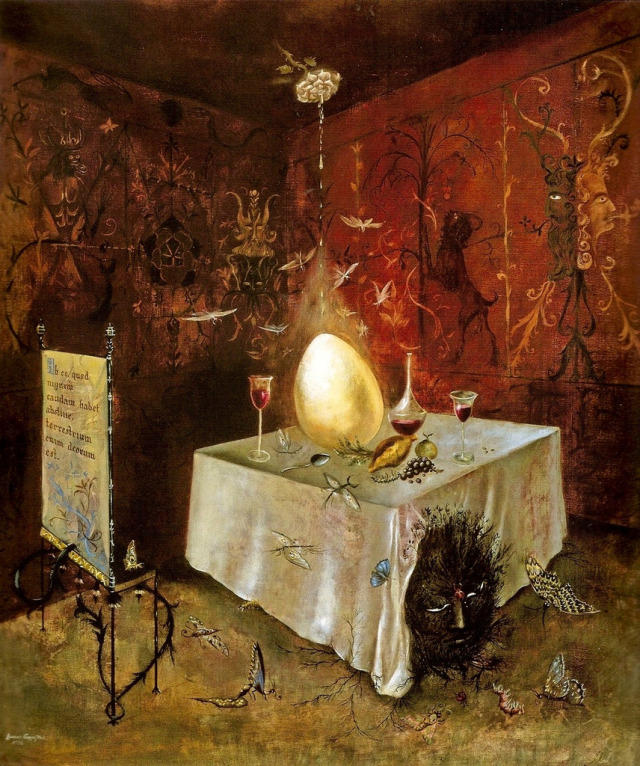

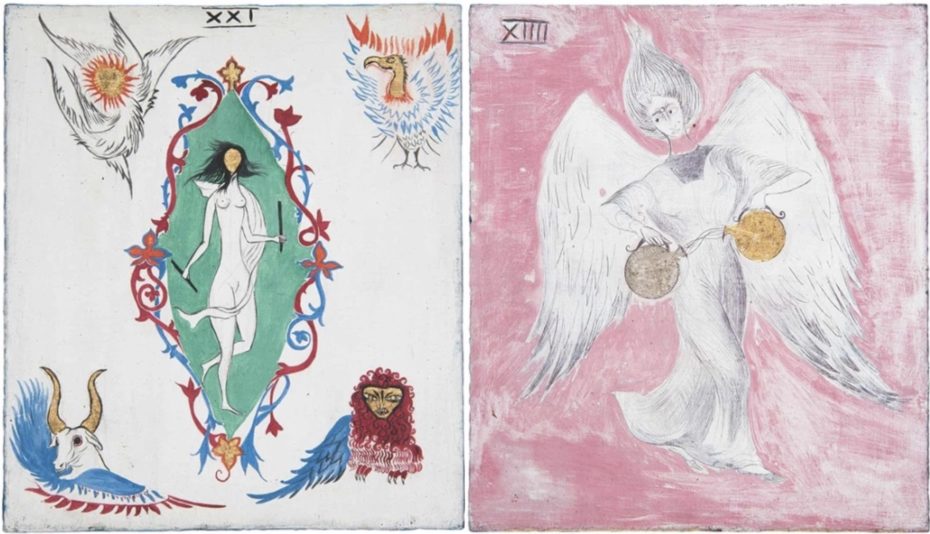

She was infinitely fascinated with alchemy, magic and the occult and these themes are to be seen repeatedly in her paintings. Much of her work – both painted and written – featured themes of entrapment and escape, where she preferred to paint female subjects over males.

She died on May 25th, 2011, in Mexico City from complications related to pneumonia having created more than 2000 works of art in her 94 years. Her work was exhibited all over the globe, fetching some of the highest prices for a living female surrealist artists. In 2005 Christie’s auctioned Carrington’s Juggler (El Juglar) for $713,000. Pop icon Madonna used Carrington and Remedios’ work as the basis for her video, Bedtime Story, which was at the time (1995) the most expensive music video made. Google commemorated her 98th birthday with a surrealist doodle depicting her painting How Doth the Little Crocodile (which was inspired by Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in 2015).

She was famously quoted for saying, “I didn’t have time to be anyone’s muse… I was too busy rebelling against my family and learning to be an artist… I painted for myself…I never believed anyone would exhibit or buy my work.” She was one of the last surviving participants in the surrealist movement of the 1930s, but .. curiously, like many of the attributes she was accredited with throughout her life, the one of surrealist seems bequeathed by association rather than by her actively engaging with the movement. Mind you, upon looking back at Leonora Carrington’s life, it’s clear as day she would never have tolerated being labelled, she was clearly in a category of her own.