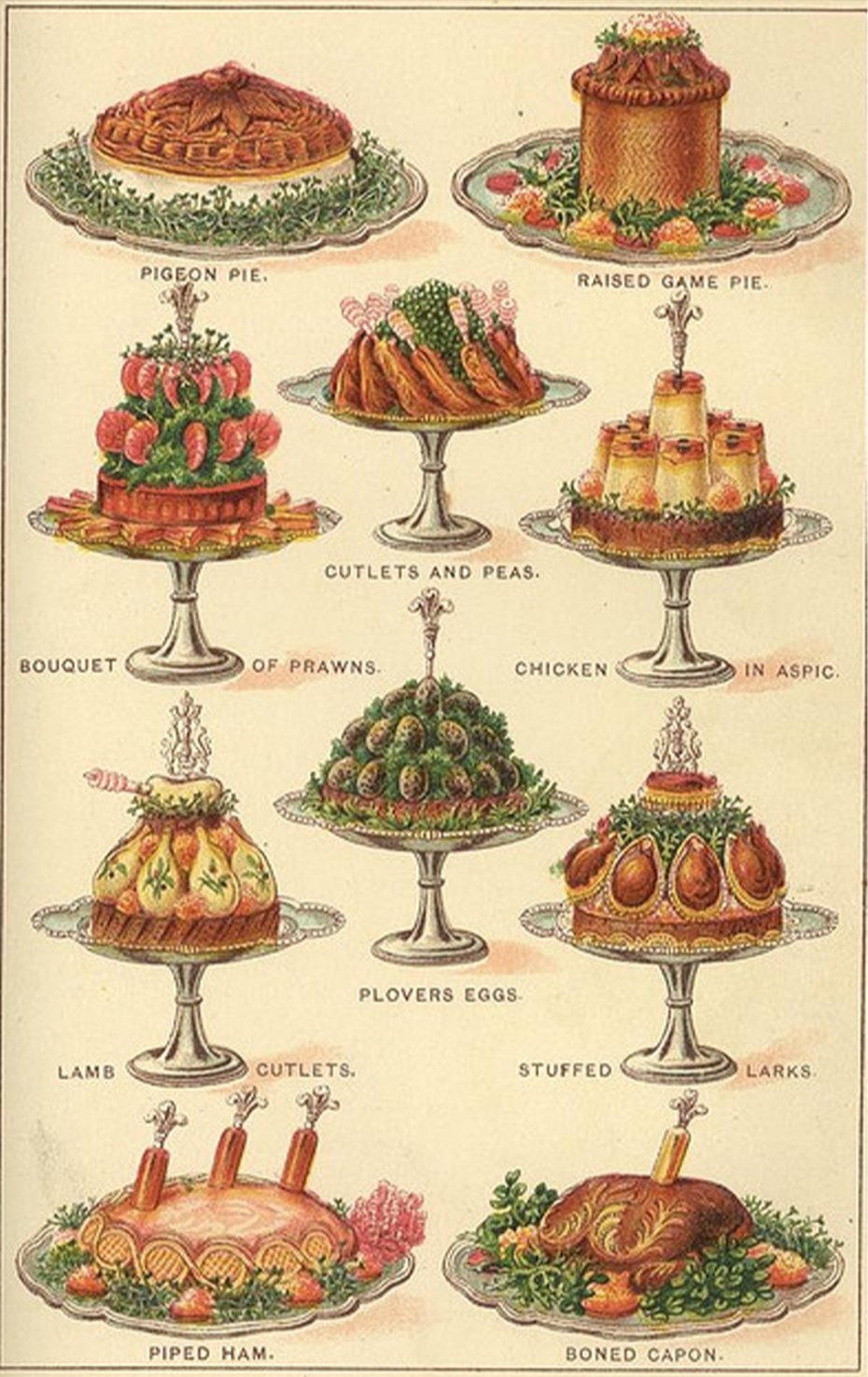

It’s hard to imagine anyone ever salivating over a quivering tower of jellied meat, but for centuries – that’s right, not just the seventies – it was the height of haute cuisine. A hundred and fifty years ago, if you were an ambitious chef out to knock the socks off your guests, the centerpiece of your holiday table would’ve likely been ham or chicken congealed in an elaborately tiered gelatinous sculpture. And believe it or not, after a meteoric drop in popularity following the 1970s, ornamental jelly is now enjoying a resurgence as edible art.

In case you’re not familiar with cooking alchemy, there are many substances that act as gelling agents. In the West, it’s most common to use gelatin, which is created from the collagen of animal bones, and meat suspended in gelatin is called an aspic. Centuries ago, every part of a slaughtered animal would be used. Skulls, hooves, and bones were boiled to make protein-rich broth. When the broth cooled, the dissolved collagen caused the water to coagulate. Cooks of the Middle Ages discovered that if they left cooked meat in the gelatin, it would be preserved for up to a month. They were soon adding egg white to clarify the broth into clear consommé, experimenting with both sweet and savoury items to plunge into gelatin, and pouring gelatin into moulds to create gleaming wiggly shapes.

Creating gelatin was a laborious task, however, requiring two days of careful simmering and then a cooling process that was difficult to consistently manage before refrigeration. Because of the effort, aspic was reserved for special occasions or for those with an expert culinary staff. It became a holiday staple throughout the world and a status symbol for the wealthy.

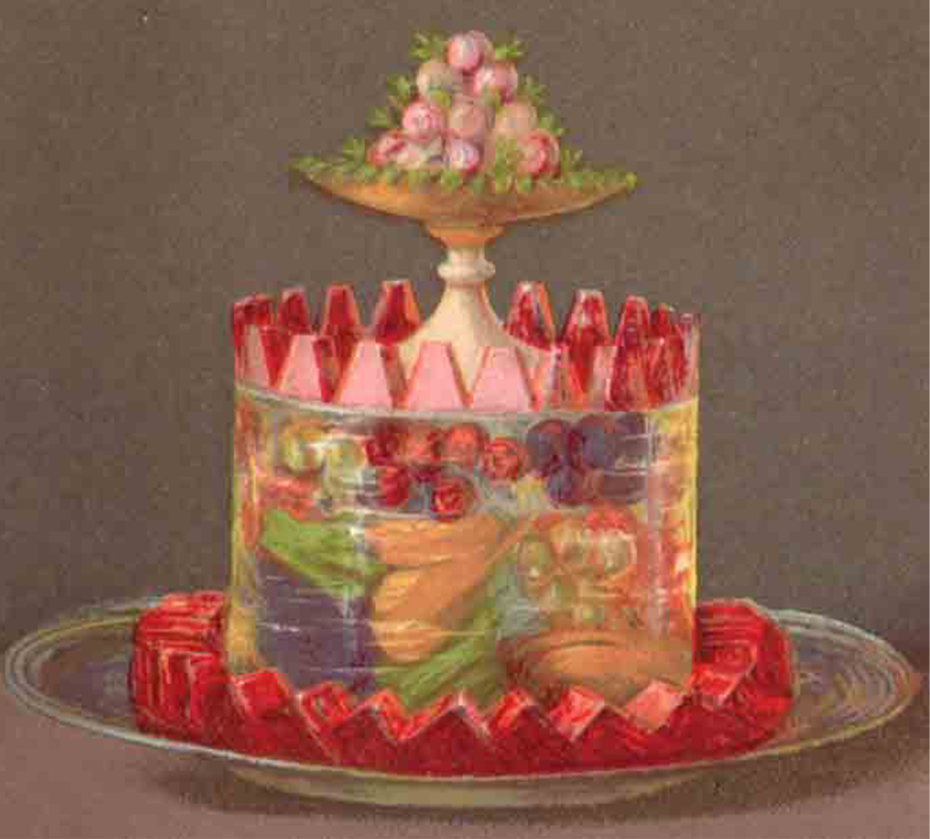

The 10th century Caliphs of Bagdad enjoyed a spiced fish aspic colored with saffron. Guillaume Tirel, chef to Charles V of France, wrote a detailed recipe for aspic in his 1375 cookbook Le Viandier, which included the admonishment, “He who would make a gelatin is not allowed to sleep.” Francesco Chieregato, an envoy of the Pope before England’s break with the Catholic Church, describes a remarkable feast in 1517 at the court of Henry VIII, “…the jellies (zeladie), of some 20 sorts perhaps, surpassed everything; they were made in the shape of castles and of animals of various descriptions, as beautiful and as admirable as can be imagined.”

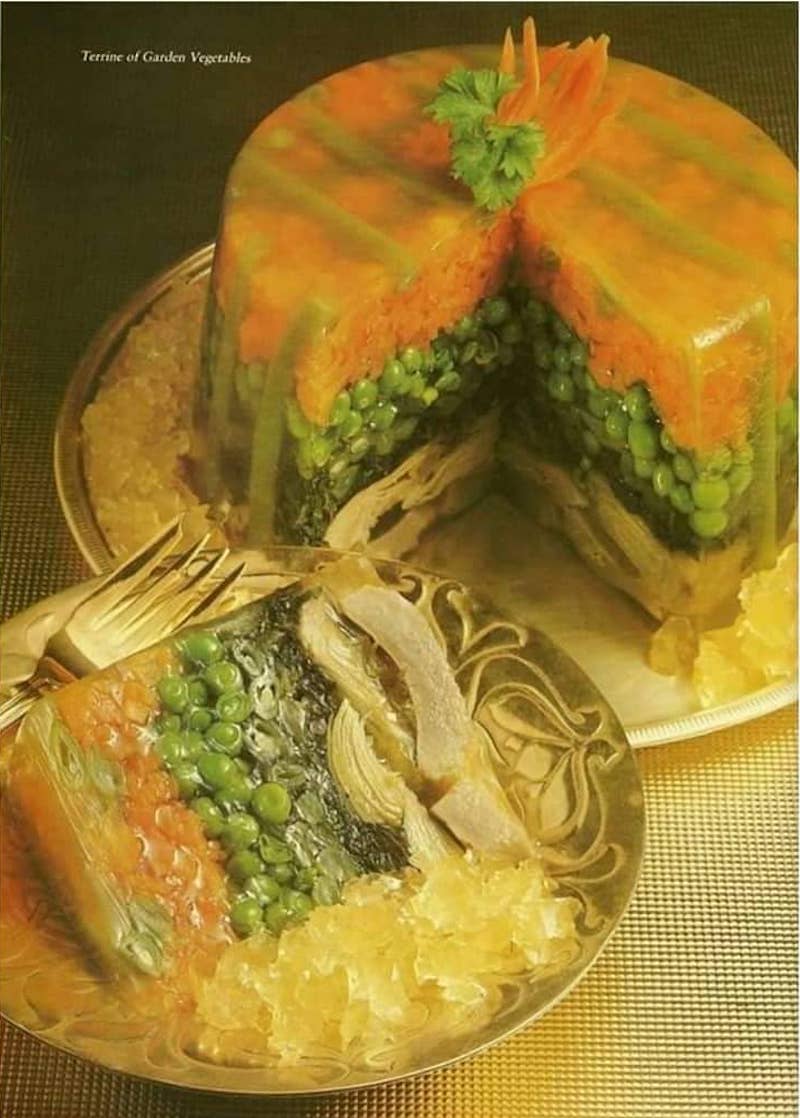

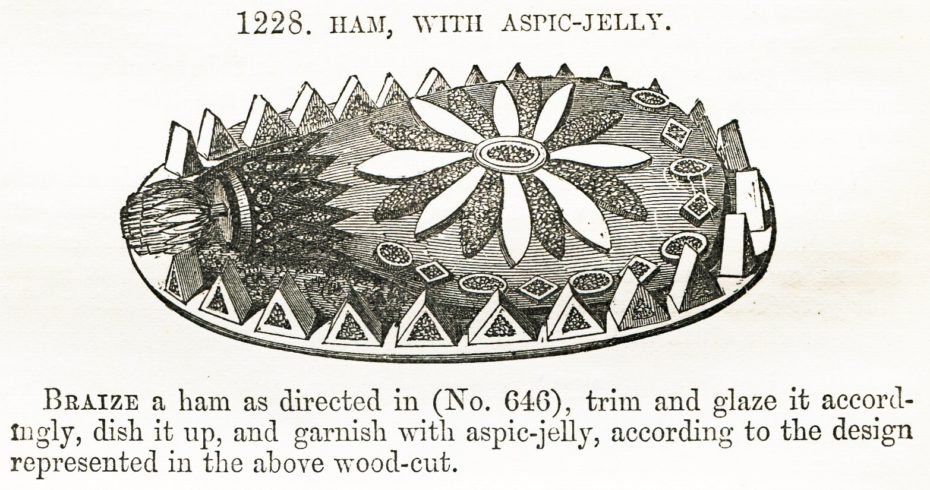

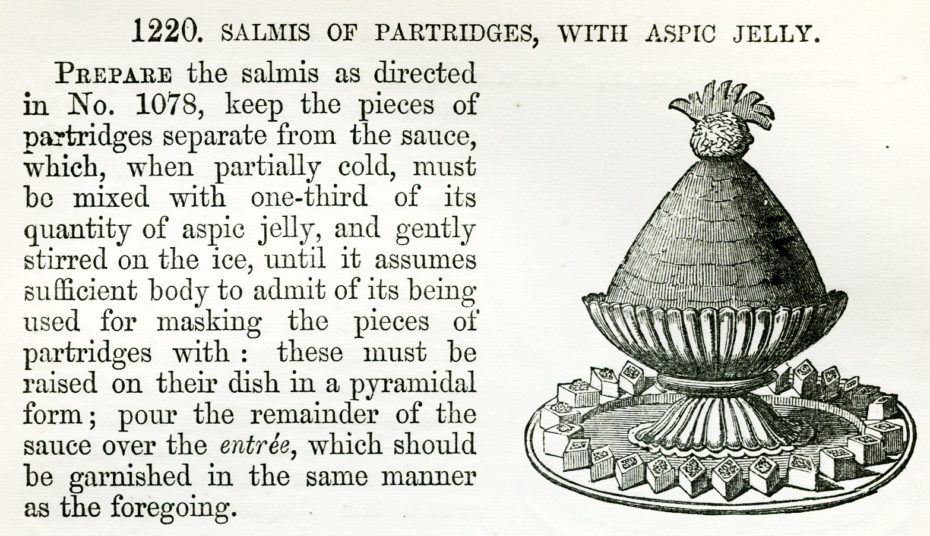

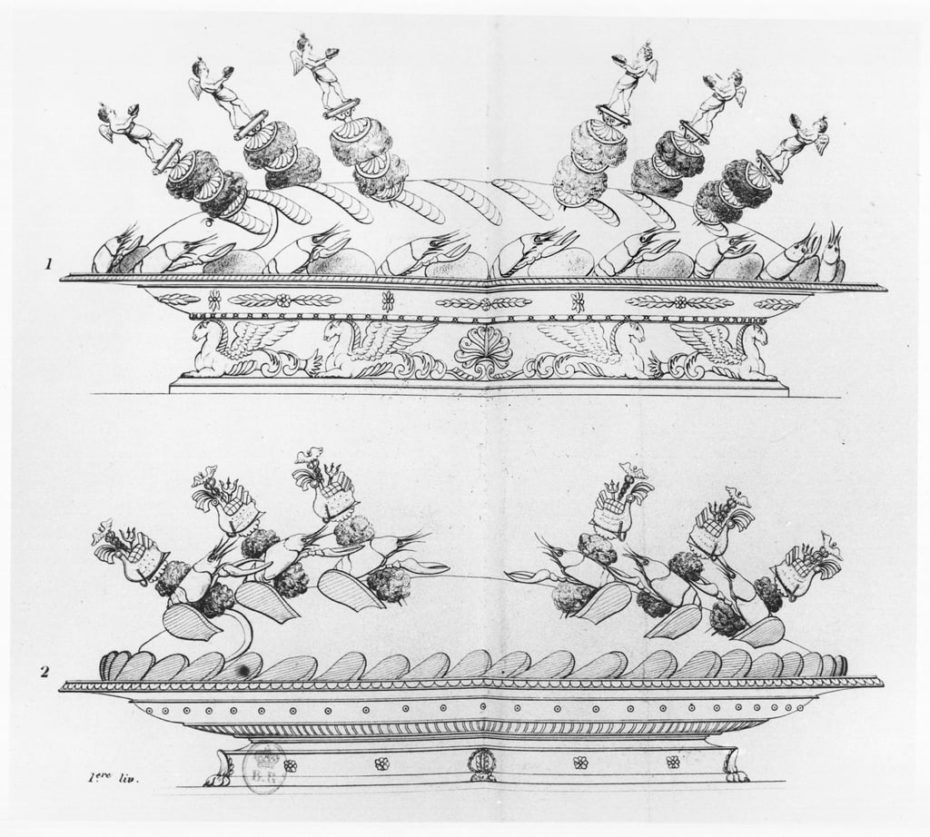

Jellies and aspics reached their zenith in the court of Napoleon at Château de Valençay. The imperial chef, Marie-Antoine Carême, came to fame building astonishing structures of marzipan and nougat that were several feet high. Seeing the eye-popping architectural possibilities of aspic, Carême wowed Napoleon’s visitors with gleaming gelatinous towers embedded with truffles and poultry pieces or studded with calf’s tongue.

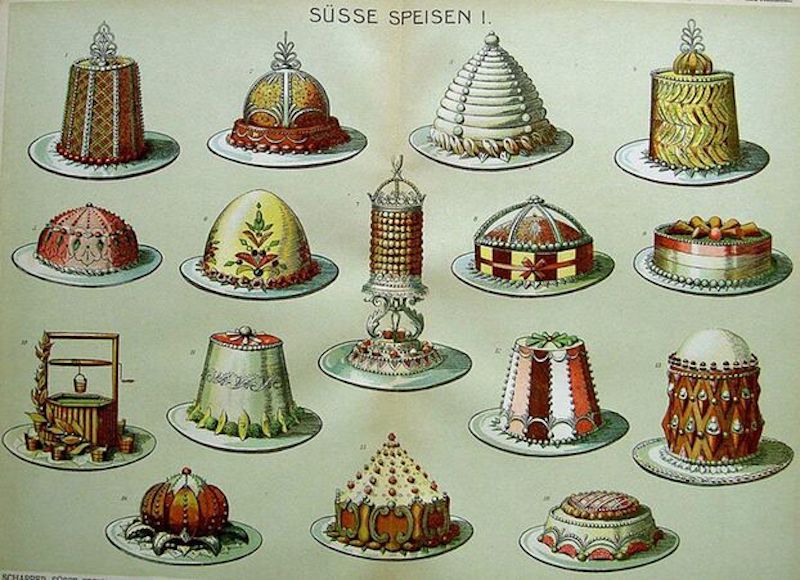

An entire section of his influential 1834 cookbook The Royal Parisian Pastrycook and Confectioner is devoted to aspic jelly moulds. Because Carême hit the aspic so hard, quivering confections of jellied meat became a staple of haute cuisine and the mark of an accomplished chef.

In 1821, Peter Cooper, the inventor of the steam locomotive, bought a factory located on Sunfish Pond along the east side of Manhattan and proceeded to pollute the waters as he perfected the manufacture of glue. While rendering animal parts into glue, the factory produced gelatin. In 1845, Cooper patented the first gelatin powder that only required the addition of hot water. Uninterested in the culinary arts, however, Cooper did absolutely nothing with his invention. He finally sold it fifty years later in 1895 to Pearl B. Wait, a struggling cough-syrup manufacturer, whose wife added fruit syrups and renamed it “Jell-O.” Without the means to promote this new product, Wait sold the Jello-O brand to his neighbor Francis Woodward, who began proselytizing the wonders of instant gelatin at fairgrounds and church socials.

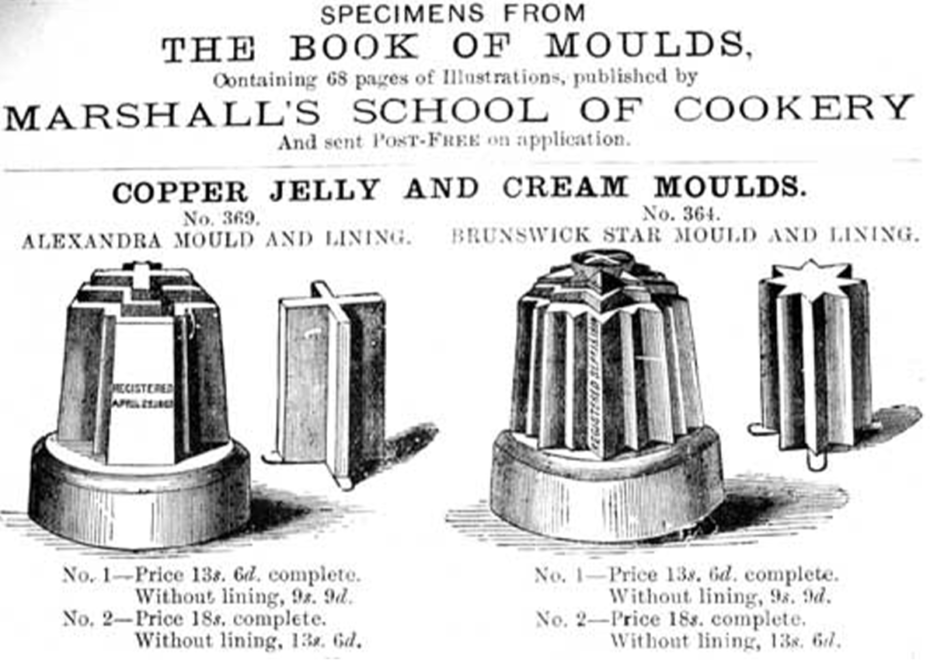

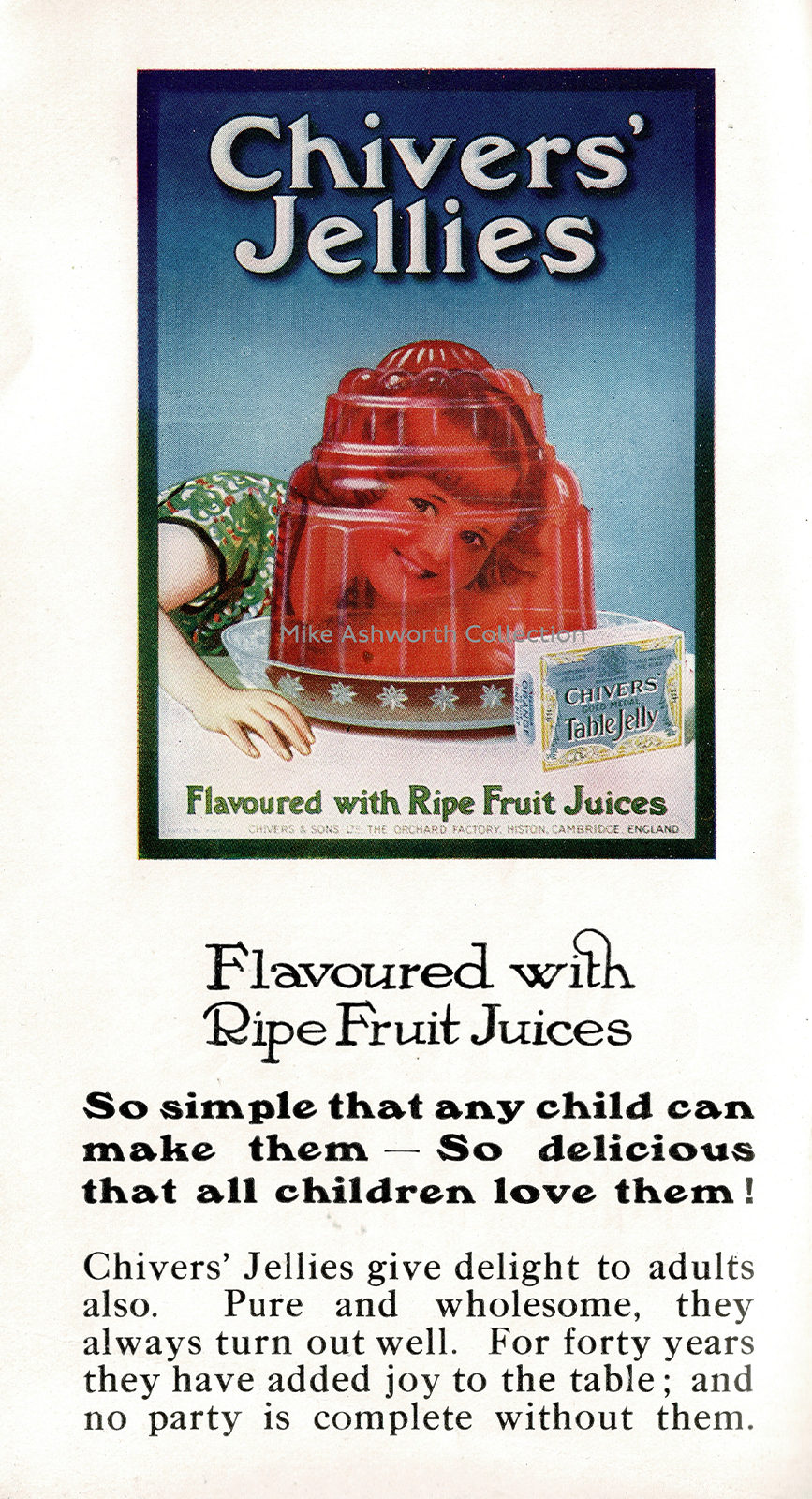

Meanwhile, in 1894, Charles Knox had invented gelatin sheets after watching his wife Rose slave over the stove to make gelatin the old-fashioned way. Knox packaged the gelatin sheets and hired salesmen to travel door-to-door showing housewives how easy it was to dissolve his gelatin sheets and turn them into wiggly semi-solid wonders. In 1896, Rose Knox published a promotional cookbook using Knox gelatin. A savvy businesswoman, she later took over the company and became the Gelatin Queen.

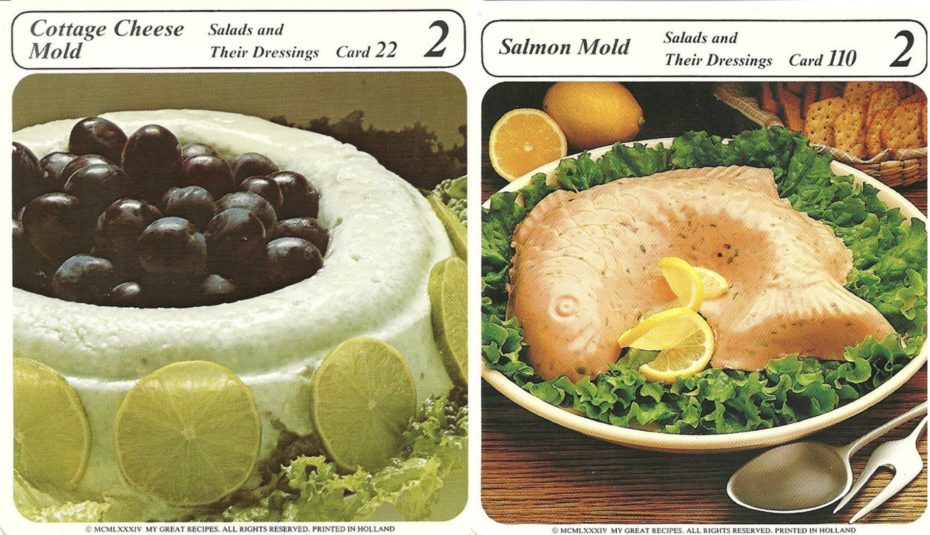

In the early 1900s, the public was bombarded with advertisements and sales pitches for gelatin. It was perfect timing for a veritable jelly explosion. Instant gelatin tapped into modern ideals of using scientific developments to unburden women’s work. It was fast and economical – a housewife could transform a family’s leftovers into a glistening centerpiece. With the ease of instant gelatin and the miracle of refrigeration, suddenly everyone could dine like a French emperor.

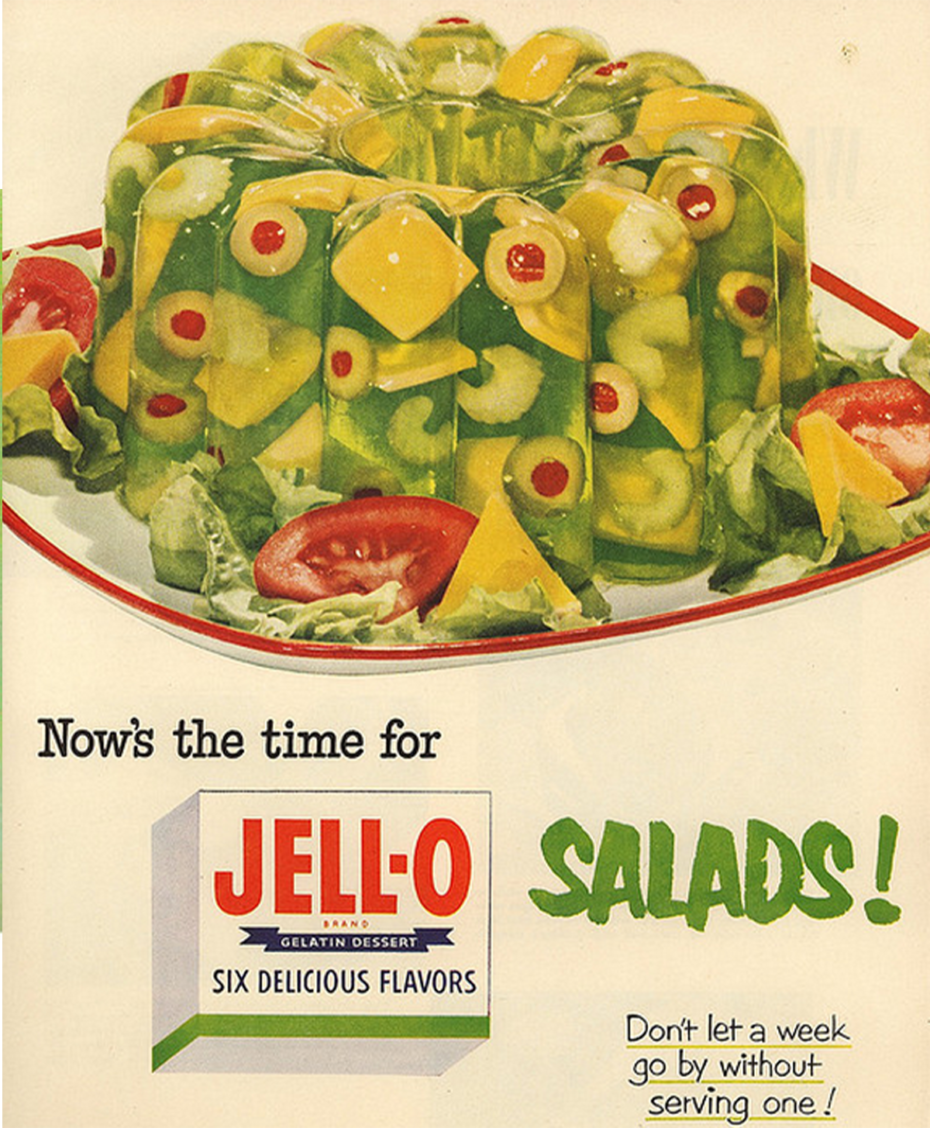

At the World’s Fair in 1904, Mrs. John Cooke of New Castle, Pennsylvania, won third prize in a Knox Gelatin cooking contest with a “Perfection Salad,” an aspic filled with cabbage, celery, and red pepper. No more messy scraping up all those loose bits of salad! Housewives went wild and started inventing their own shimmering salad sculptures.

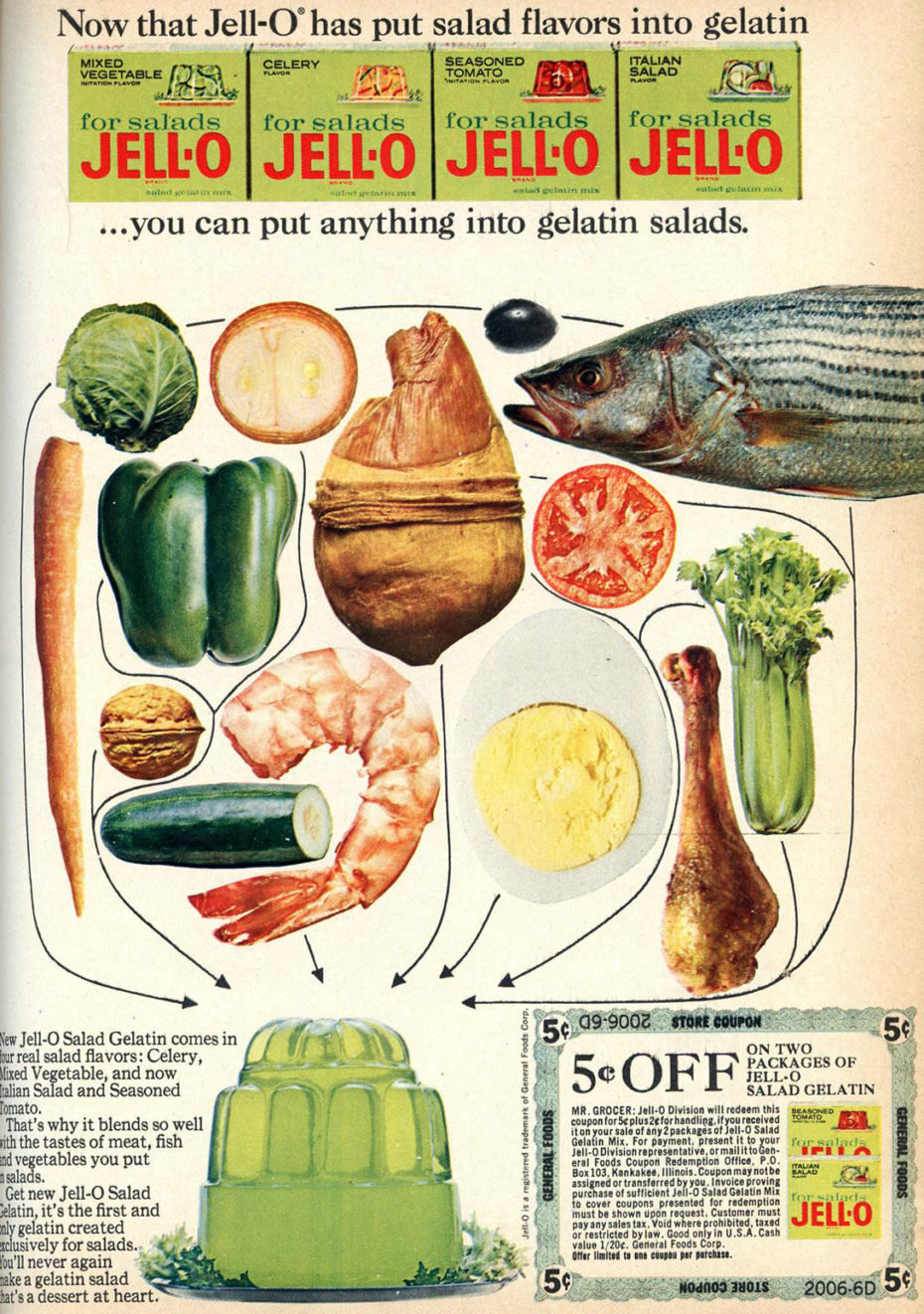

Gradually, the image of gelatin as cheap and convenient eroded its prestige. In World War 2, Jello-O was advertised as a way to stretch war rations and make them more appetizing. After the war, convenience food corporations continued to bombard the public with ways that Jell-O could ease the burdens of a busy housewife. Brand-specific cookbooks were produced by companies pushing their products, leading to notoriously unappetizing recipes. At one point, General Foods owned the Jell-O, Hellmann’s Mayonnaise, and Libby Canned Fruit brands, mixing ingredients from each of these brands together in unpalatable combinations. Tuna and mayonnaise in Jell-O decorated with pineapples, anyone?

After becoming a mockery of itself, aspic lost its place at the table. There is a new generation, however, embracing gelatin for its nostalgia, its sculptural possibilities, and the ultra-kitsch of wobbly mountains of meat studded with olives. Emily Marshall-Garrett is a motion picture food stylist. She’s the culinary genius who created that wobbly emerald green mountain of Perfection Salad in Justin Bieber’s video Yummy. Raised Mormon in Los Angeles, she was fascinated by Jell-O at family reunions. The Mormons continue to be fixated on Jell-O, so much so that Utah is also called the Jell-O Belt. When she was tasked with creating a mid-century meal for the ABC Family mini-series The Astronaut Wives Club, she laughs that she was overly qualified for it. The jelly mould centrepiece that she created for The Astronaut Wives Club launched a career in Jell-O.

“For me,” she mused, “gelatin touches on so many categories. It is coded with so much meaning: gender roles; class consciousness; power & control; Americana; white culture; Christian culture; contemporary and historic food trends; the rise of industrial food in post- World War 2 America; Southern heritage; Mormon culinary traditions; Sci-fi movie space food; traditional French cuisine.”

Siew Heng Boon also comes to jelly art through her heritage. Now based in Sydney, she grew up in Asia where jellied desserts have always been in vogue. In Asia, however, it’s much more common for jelly to be made from agar, which is derived from seaweed. After her mother was gifted with a jelly art creation, Boon was inspired to take a course on it. She now owns Jelly Alchemy and produces stunning jelly art, often with Asian motifs of koi and peony…

“Besides being edible and delicious,” she says, “the crystal clear jelly that acts as a canvas makes the art within look as if it’s are encased in glass.”

There is something truly compelling about the sculptural possibilities inherent in Jell-O as well as its texture and sheen. Marshall-Garrett sums up the allure succintly, “Jelly molds are shiny colorful vehicles for visual and culinary maximalism, with a heavy side order of nostalgia.” Perhaps it’s time to bring the aspic back to the centre of the table – minus the mayonnaise and tomato soup.

About the Contributor