The generation that came of age in the aftermath of the First World War and the Spanish Flu did a lot more than just bob their hair and drink all the time. Well, they did do those things too, but let’s take a closer look at those party animals of the roaring 20s a century later, and revisit the sparkling youth movement infamously known to history as the Bright Young Things…

They were blue blooded aristocracy at a time when the class system in Britain was starting to crumble in aftershocks of war. Their parents came of age around the turn of the century, but it might as well have been in antiquity for all that they saw any commonality with older generations. Members like Noel Coward, David Tennant, and Elizabeth Ponsonby were rebelling against the morbid mood and grief Europe had known during the war they were too young to fight in. They seized opportunities to express themselves through mediums like clothes, music, and sexuality.

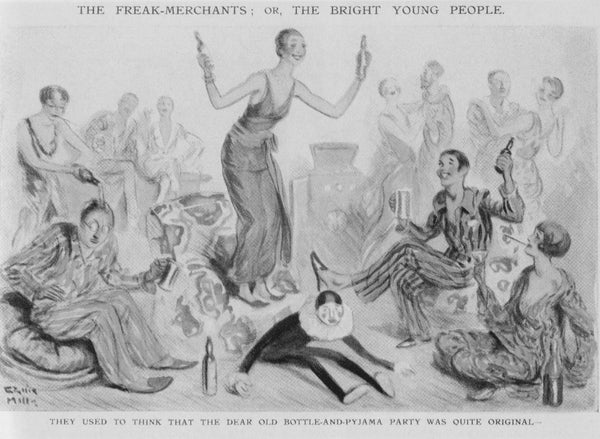

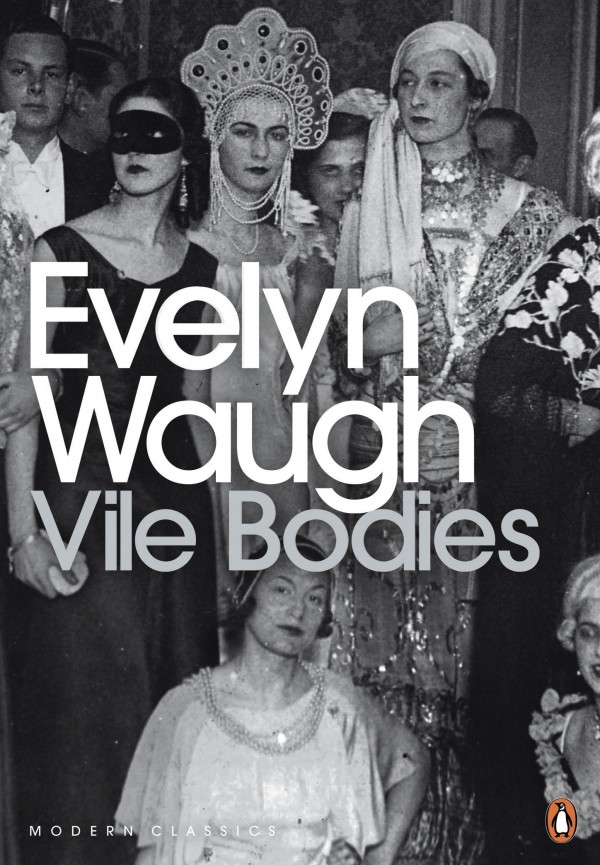

Famously, they held large scale treasure hunts, but mind you, these hunts were nothing like your average Easter egg hunt. These were clandestine alcohol-fuelled scavenger hunts that played out on the glittering streets of West London. Extravagantly-dressed Bright Young Things, also known as the BYP’s (Bright Young People) made a spectacle of themselves on London’s public transport system, causing a nuisance wherever they went. They piled into fast cars and tore off through the city to follow the clues, chased by paparazzi hoping to get snap a moment of high society scandal. They went hand in hand with weekend house parties, elaborate pranks and theatrical fancy dress parties, where men and women were both encouraged to dress how they felt rather than how society viewed them. A fancy dress theme was always paramount, and androgyny was often a common one – men were encouraged to be effeminate, and women dared to wear men’s clothes for comfort and pleasure. At their lavish costume parties, light and airy fabric like silk and chiffon reigned, as well as bold patterns, sequins, feathers, and fringe.

Although homosexuality was still very much illegal in Great Britain in the 1920’s, gay men and women were accepted within the ranks of the Bright Young Things, and in fact, no previous youth movement had been so hospitable to them. They were only too willing to follow their passions and buck the constraints that society, and their families, tried to place on them.

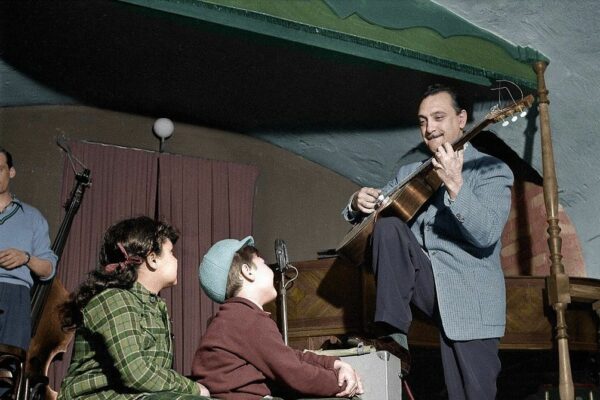

They were both the beautiful and the damned; the youngest children of parents grieving sons lost in the Great War, and seemed to share a collective badge of insecurity no matter how fabulously they entertained themselves. Excessive drinking and experimentation with drugs was practically a requirement. Their haunts included the Embassy Club on Old Bond Street, Café de Paris and the Cavendish Hotel for early morning after-parties at the bar following long nights at the Gargoyle Club, founded by socialite David Tennant, the younger brother of a promising poet who had been killed in action in World War I. The private members’ club existed on the upper floors of a Georgian townhouse (accessible only by a rickety four-person lift). None other than French painter Henri Matisse helped decorate and design elements of the club which included a private apartment, a large ballroom, Tudor room, coffee room, drawing room and roof garden for dining and dancing. On opening night, the guest list included Virginia Woolf, Nancy Cunard, Adèle Astaire, as well as members of the Mountbatten, Guinness, Rothschild and Sitwell families.

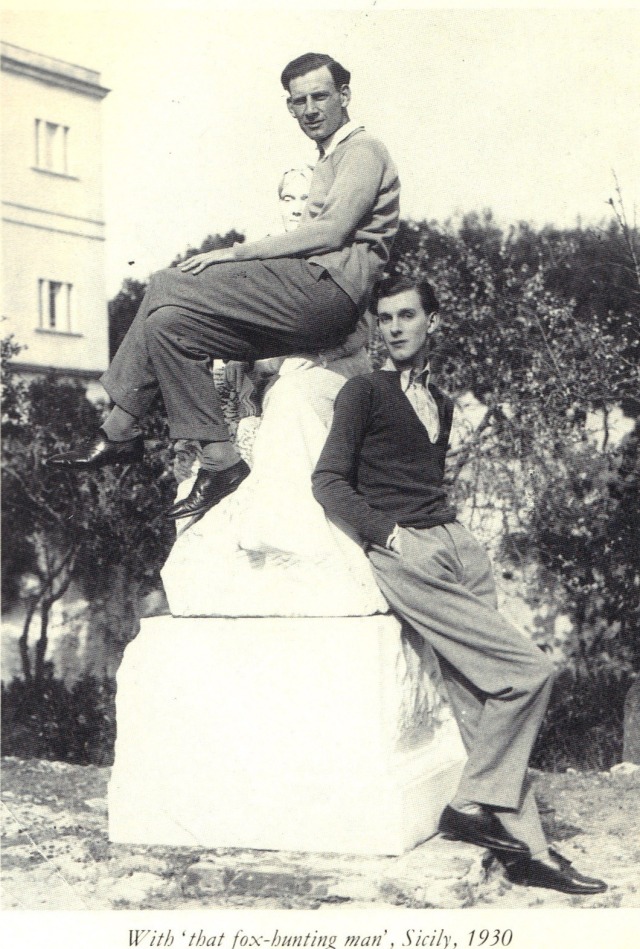

Cecil Beaton, the famous photographer, lover of Greta Garbo, darling of the Royal family, captured endless images of these fine specimens of British eccentricity. Enchanted with the dazzling lifestyle of the young aristocrats, he decided to photograph them to ingratiate himself and his images are some of the most famous moments captured of the flamboyant set. Beaton focused on beauty and elegance, and his subjects were only too willing to dress up and pose in front of elaborate backgrounds that Beaton devised.

The “It Girls” seemed to change from season to season and there was always a new “up and coming man” every few months. Cecil’s own glamorous sisters Nancy and Baba were ripe pickings for media interest, as was Stephen Tennant, considered “the brightest” of the “Bright Young People”. He is widely considered to be the model for the character in Nancy Mitford’s novel Love in a Cold Climate, who uses his exceptional good looks and charm to establish a place within the homosexual milieu of the European aristocracy.

While Cecil Beaton adored his subjects, the press that dogged these young party animals formed a different relationship. The press and paparazzi quickly became aware of the public’s thirst for compromising photographs and outrageous stories that leaked from the wild and hedonistic parties. It was rare not to find salacious details of a previous night’s party in tabloids such as The Tattler or even mainstream newspapers such as The Times. Even within the aristocracy’s social circle, the secrets were too good not to share. Newspapers began to recruit members of the Bright Young Things to write the society news and gossip columns for them. It was practically part of a BYP’s morning ritual to pick up the paper and read about themselves as they nursed a hangover. They were accused of being exceptionally narcissistic, and have often been blamed for starting the modern cult of celebrity.

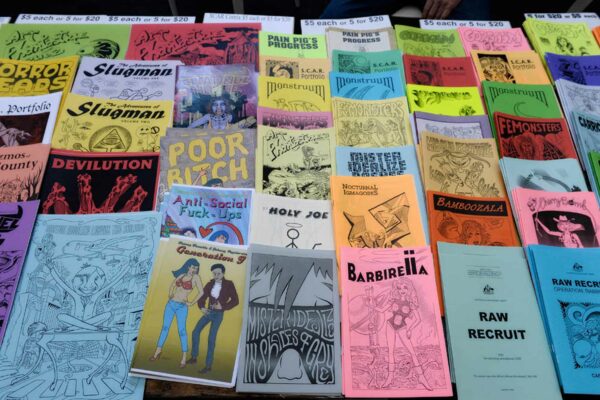

Many members of the BYP’s were also aspiring writers, and with such entertaining private lives, the youth movement soon had its very own literary form known as ‘the party novel’, in which insider authors, such as Nancy Mitford and Evelyn Waugh, could share all the gossip, frivolity and impending tragedy that unfolded amidst their friendship groups, while protecting the names of the innocent (and not so innocent). The public both loved and hated the Bright Young Things; wanting to emulate the fashion and glamour, while also look down their noses at it all.

The age of the BYP’s rose in the 1920’s, and fell when the decade ended. Then came the economic crashes of the 1930’s, when society was no longer willing to indulge their ways. Then came the second World War, and society was ripped apart all over again. This brief but unforgettable era of British bohemian excess lives on in the literature of the movement’s celebrated novelists, in the brushstrokes of its artists and the intriguing captures of its photographers. A century later, they somehow continue to fascinate and inspire us. Might we see a return of the hedonistic and decadent underworld of the BYP’s? With our dancing shoes and fancy dresses gathering dust in the wake of a pandemic, we’d be foolish not to think so.