They aren’t remembered for their political or intellectual outpourings, nor for their radical actions in the streets. The only weapons of the Zazou were dress, speech and attitude, and yet, this Parisian subculture somehow came to be a thorn in the side of Nazis and French Fascists. Throughout history, fashion has always been a reliable thermometer for society; subtle behavioural expressions can say so much without words; and the Zazou’s visual identity conveyed the entirety of their cause. Their character was one of passive contempt for the establishment and a reluctance to follow the conventions of the past. Taking their lead from the earlier French Jazz culture of the 1920s, theirs was a non-violent cultural resistance; an understated protest of provocative dressing and frivolous individualism…

The late 1930s saw the rise of a controlling socialist state which was suddenly replaced by the invading Nazi regime in 1940. The country was then partitioned by the Nazis who empowered an extremely conservative, Catholic dominated, authoritarian, and racist puppet government to run both the occupied territory in the north and the unoccupied land in the south from the town of Vichy. Now holding an estimated 10 percent of the total adult male population of France as prisoners of war, the Nazis treated Vichy France as a client state, demanding tribute in gold, food and supplies. In the face of France’s demise, the Zazou blossomed like a lone winter flower. Never a formal movement, nor an organisation with any base, the glue that held the individuals together was an adherence to Jazz and fashion.

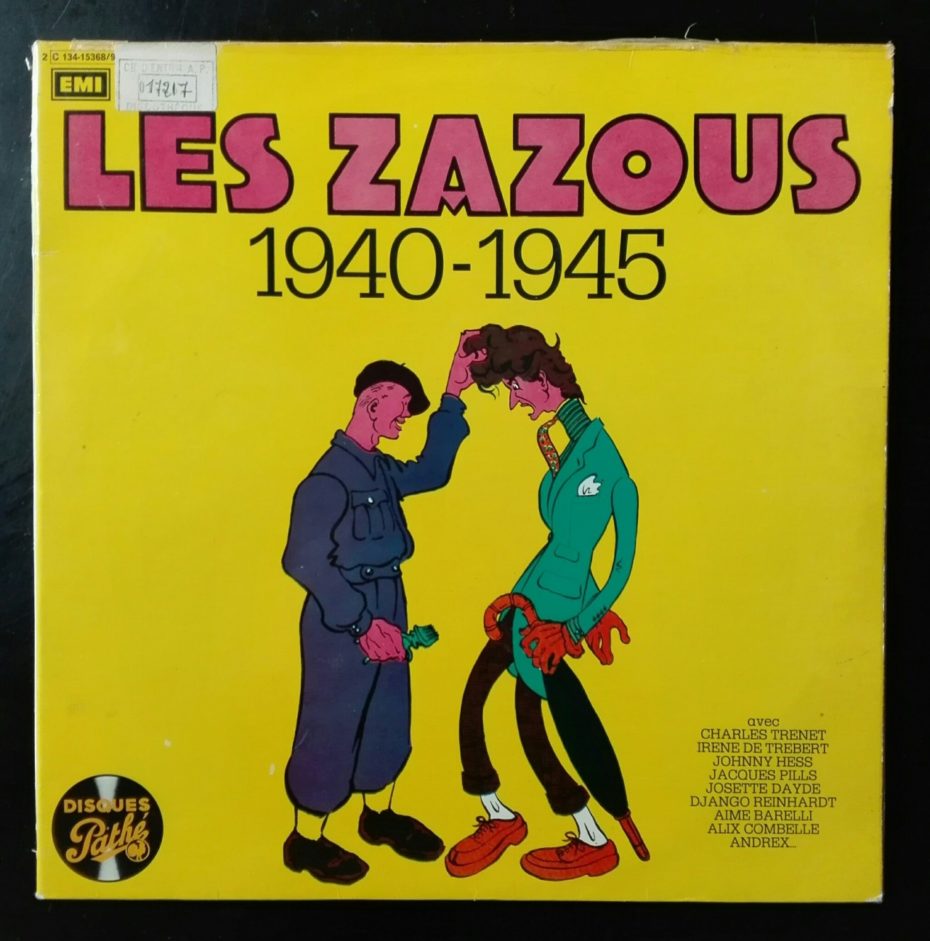

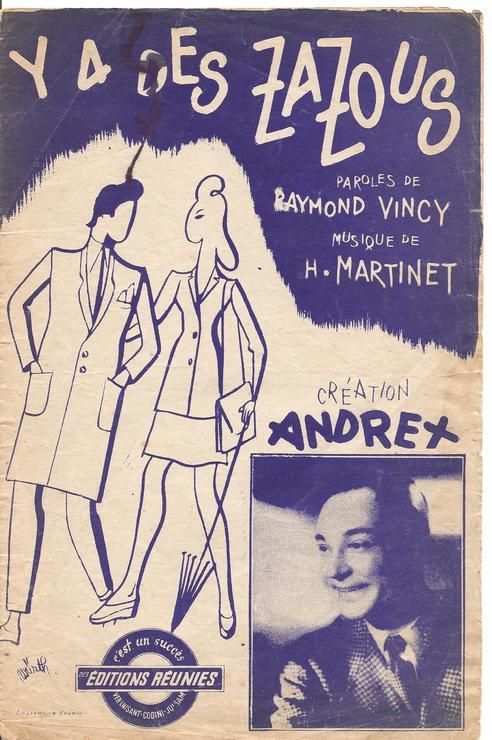

The Nazis had forbidden Jazz, which was branded as a mechanism of cultural degeneration, but a decade earlier, the 1920s had seen the African American Jazz invasion first sweep through Paris, reviving a war-weary, war-torn France. Swing clubs promoting African American Jazz had offered a new, relaxed, alternative identity for youth culture, in contrast to the old-school, regimented colonial models. The name Zazou was allegedly derived from a line in a song from the African American Jazz musician Cab Calloway – ‘Zah Zuh Zahby’. Cab Calloway’s billowing oversized coats and excessively long watch chains would also become essential fashion elements for the Zazou. Jazz not only created an awareness of cultural diversity and inclusion but it was something fresh, new, fun and intoxicating, very much not of the France of old. The establishment saw it as a destructive intrusion into French culture and values and the Zazou would use the perceived un-Frenchness of Jazz as a poke at conservative French society and authority – aka, the Vichy.

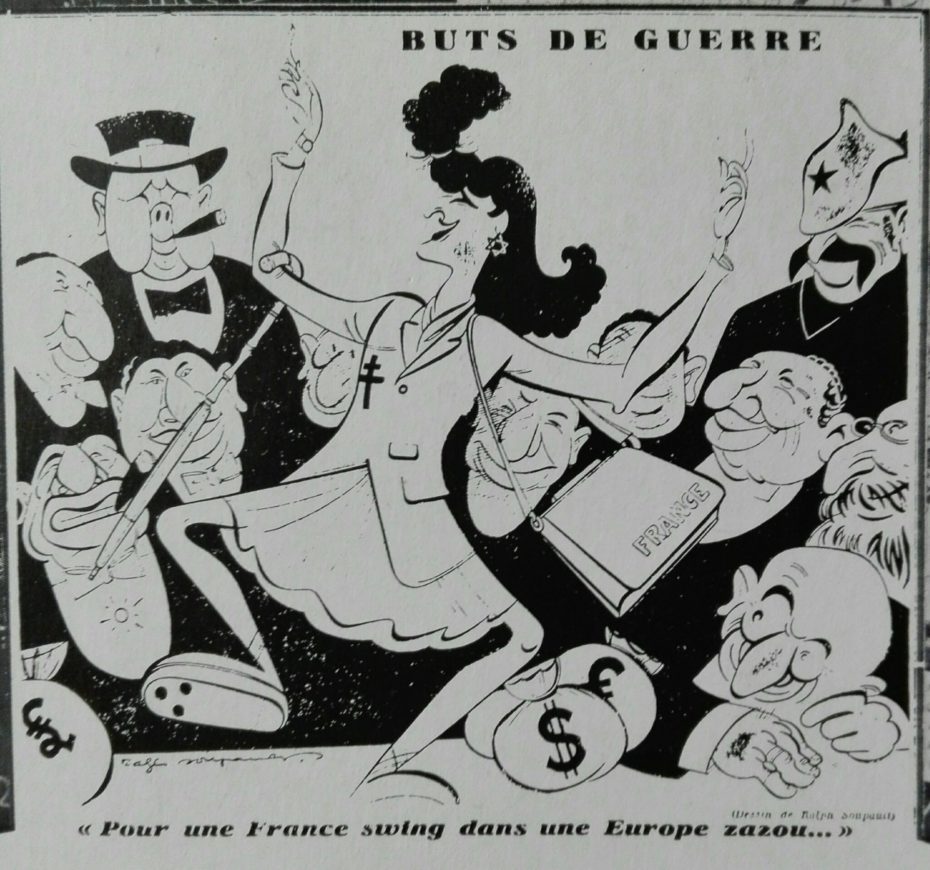

The conventional view is that the Zazou era ran from around 1938 to 1942. A badge for the wealthy young and idle, Paris’s wartime “swing kids” created a rebellious fashion identity and made sure the authorities noticed it by flaunting their style in neighbourhoods most frequented by Nazi officers. They didn’t hide away in clandestine underground bars, but rather boldly squatted cafés like the Pam Pam right on the Champs-Elysées and the Boul’Mich in the Latin Quarter, talking loudly and passionately about jazz. The Zazous also had an argot (slang) that adopted English words and phrases, especially the word “swing” which became, in the words of Jean-Claude Loiseau, “un mot passe-partout” (an all-access password).

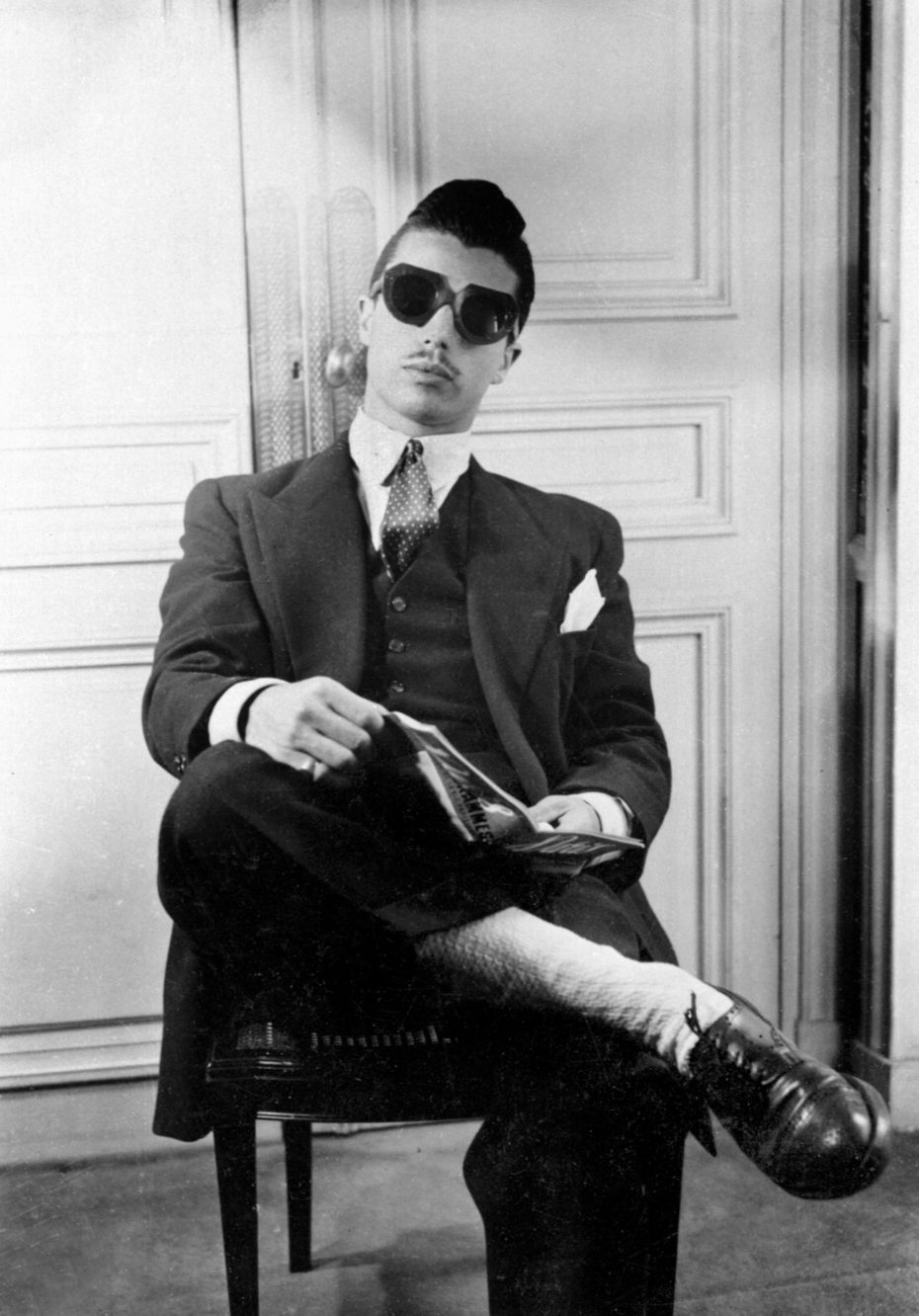

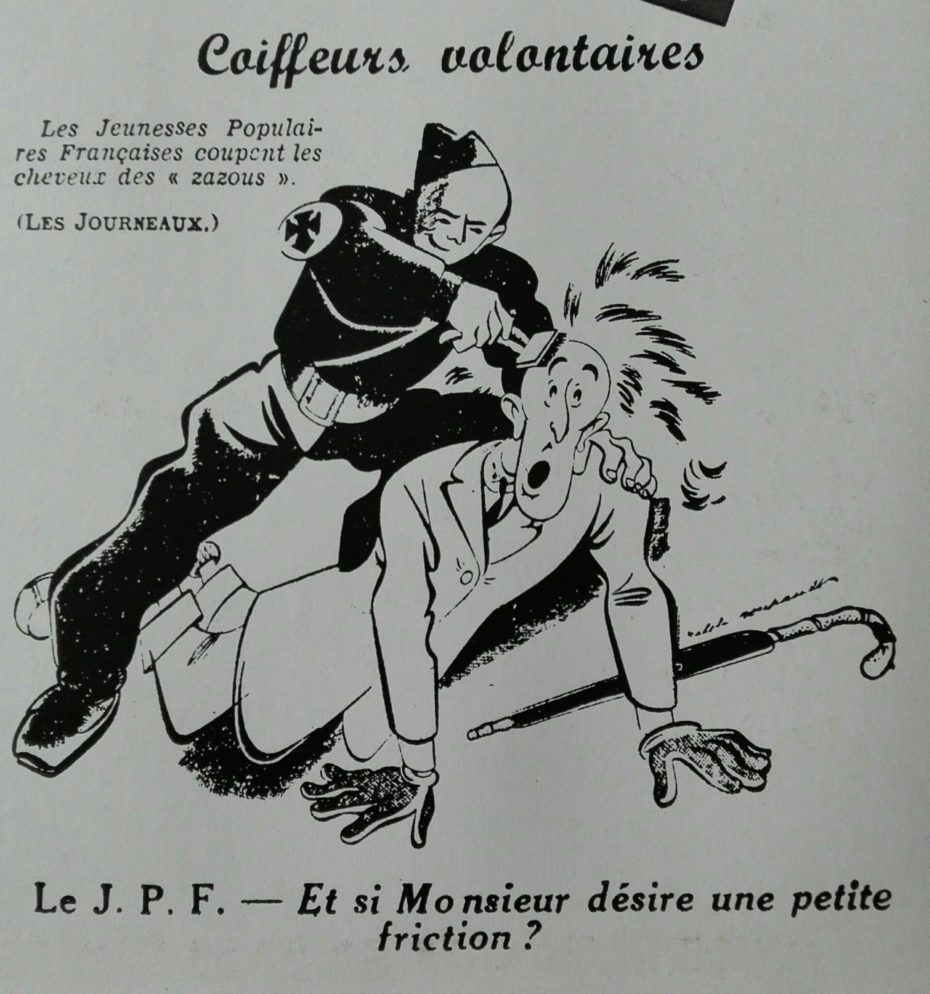

The male Zazou wore oversized and overly bright jackets, adorned with large pockets and a thin, tight tie. His trousers were short, revealing colourful socks and thick soled suede shoes. Hair was often long and unkempt; big and wild and frizzy, possibly in protest to a law that required all barber shops to collect hair cuttings for the war effort. Umbrellas were an essential accessory, perhaps a lift from the British, ‘Le Style Anglais’, a foreign import to further tease their own authorities. With the war this ‘wasteful’ use of fabric was a slap in the face of the government-directed rationing of materials.

British historian W.D. Hall aptly described the female Zazou look: “the girls favoured tight roll-collar sweaters with short, flared skirts and wooden platform shoes, sported dark glasses with big lenses, put on heavy make-up and went bare-headed to show their dyed hair, set off by a lock of a different hue.”

Bouffant blonde hair (with their roots deliberately showing) was the hairstyle of preference for Zazou ladies, together with brash bright red lipstick, modelling themselves on the Hollywood stars of the 1930s. Tartan was also abundant, yet another foreign import to irritate the authorities with. You can see how this could have been irritating to a régime which sought to create austere, pure women, and virile, wholesome men.

Christian Dior himself would later give his own review of the Zazou look, “Hats were far too large, skirts far too short, jackets far too long, shoes far too heavy.” Still an unknown aspiring designer in the 1930s, Dior served as an officer of the French army, but after the surrender, he went to a work in Paris at a design house that would consistently dress the women of both Nazis and French collaborators. During this same time, his younger sister, Catherine, was working for the French Resistance. “I have no doubt that this Zazou style originated in a desire to defy the forces of occupation and the austerity of Vichy. For lack of other materials, feathers and veils, promoted to the dignity of flags, floated through Paris like revolutionary banners. But as a fashion I found it repellent.”

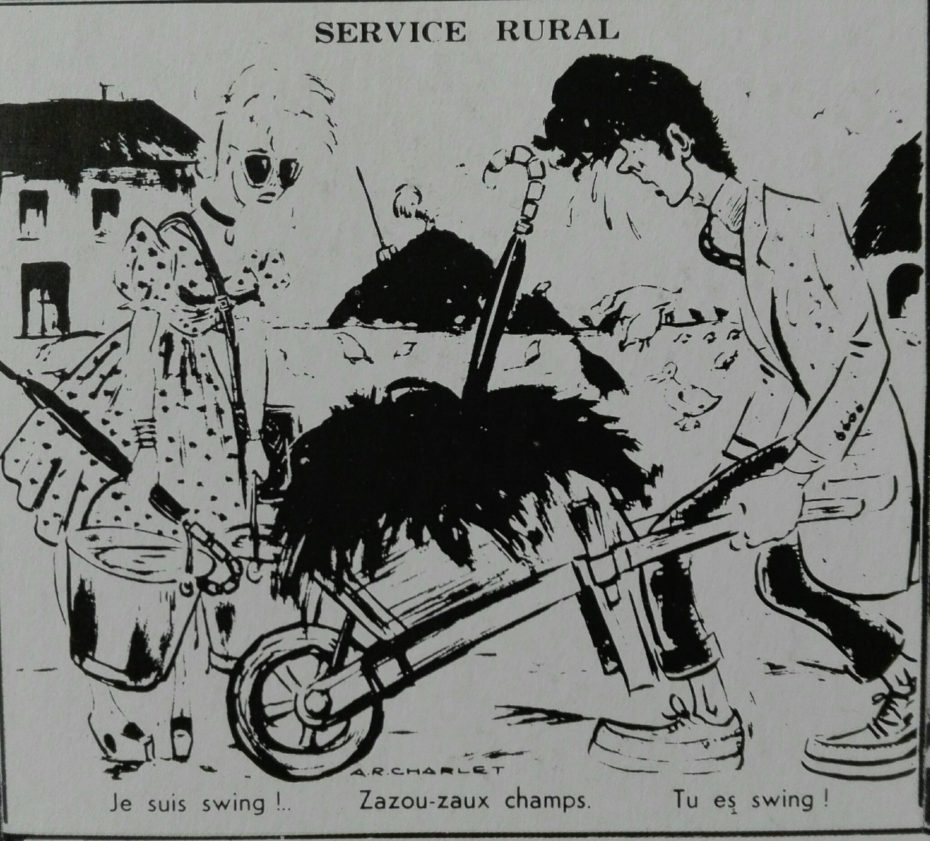

In 1940, the French press was awash with Vichy-sponsored anti-Zazou articles, claiming the very bones of French society were rotting. When anti-Zazou propaganda in the Vichy-controlled press didn’t seem to quell the youth movement, some Zazou were rounded up and assaulted, their heads shaved and sent to ‘worksites’ set up by Vichy for their ‘re-education’. Cafés raids became more frequent, and any lively or “swinging” venues were targeted as the unhealthy haunts of perverted boys and idle little girls. A provocative and perhaps more unpopular trait of the Zazou was to demonstrate that they had money and time for leisure in the face of austerity, which didn’t rub everyone the right way.

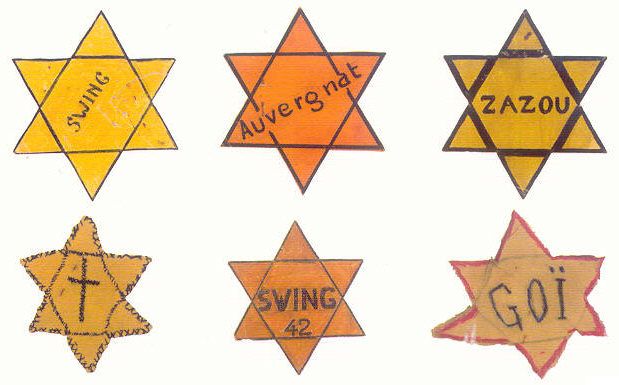

The apparent lack of work ethic, the accusations of laziness and the dandified image of the Zazou were seen as a threat to the French youth revival and Vichy wanted it stamped out. Tarred with the same brush as the Jews, more Zazou were rounded up, and when the occupying Germans imposed forced labour in France in 1942, the party was well and truly over. Nobody wanted to be caught appearing idle or odd. The Zazou were now being deported to the German concentration camps, accused of sedition and homosexuality.

The Liberation of Paris in 1944 by the Allied forces saw some Zazou joining the armed struggle to rid the city of the Nazi occupiers. Never an organised political group, their contribution was not accepted by the mainstream political movements. In fact, post-conflict socialists branded them the equivalent of upper class twits who hadn’t cared about the war until the end was in sight.

One might see the Zazou cultural resistance as an arts, music and fashion skirmish, pitching the alternative fashion of a faction of the captive French against the slick designer German Army uniforms – a real battle of style and its accompanying messaging. Umbrellas would be substituted for guns, long hair for helmets, bright patterns for military bling and Jazz melodies for Strauss’ waltzes. The Zazou deployed both the imported American Jazz culture and the dressing in ‘un-French’ overseas fashions to draw attention to where they thought France had lost the plot.