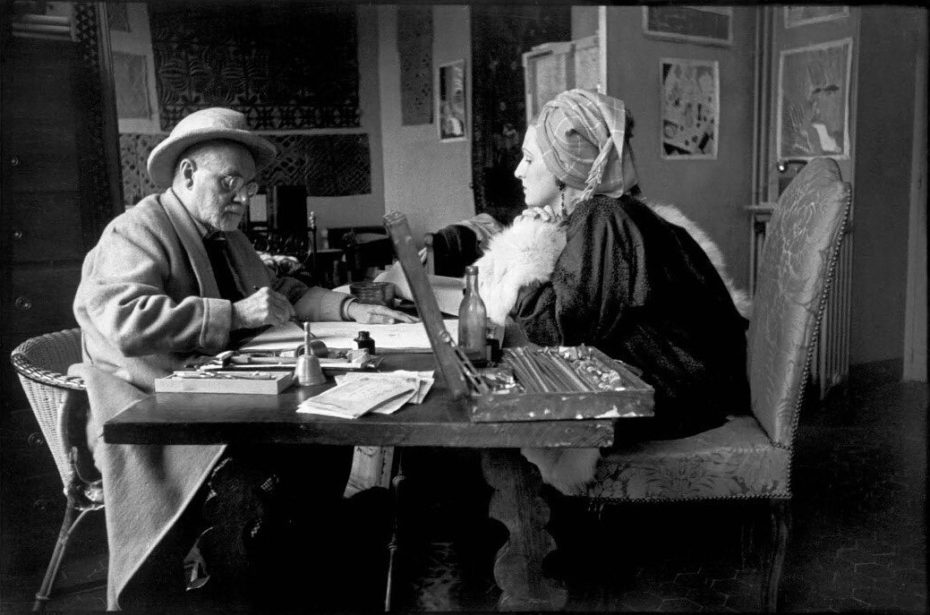

The saying is that behind every great man there is a woman. In the case of Henri Matisse, that woman was not considered to be his wife of 40 years, but a penniless refugee who was barely surviving in 1932, when she found temporary work with the French modern master. Her name was Lydia Delectorskaya, and while she was never Henri’s lover, such was her influence over the Matisse household, that his wife insisted “it’s me or her”.

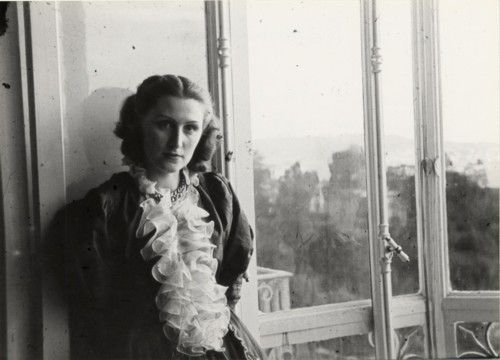

“Madame Lydia”, as she eventually became known, had never heard of Henri Matisse when she started working for him as a studio assistant in 1932. She had spent most of her 22 years trying to survive childhood after she was orphaned at the age of 12 and then raised in poverty by her aunt, having fled to France to escape the Russian Revolution. Upon arrival in Paris, she was accepted into the Sorbonne to study medicine but couldn’t afford the fees and ended up settling in Nice’s tough Russian emigrant community.

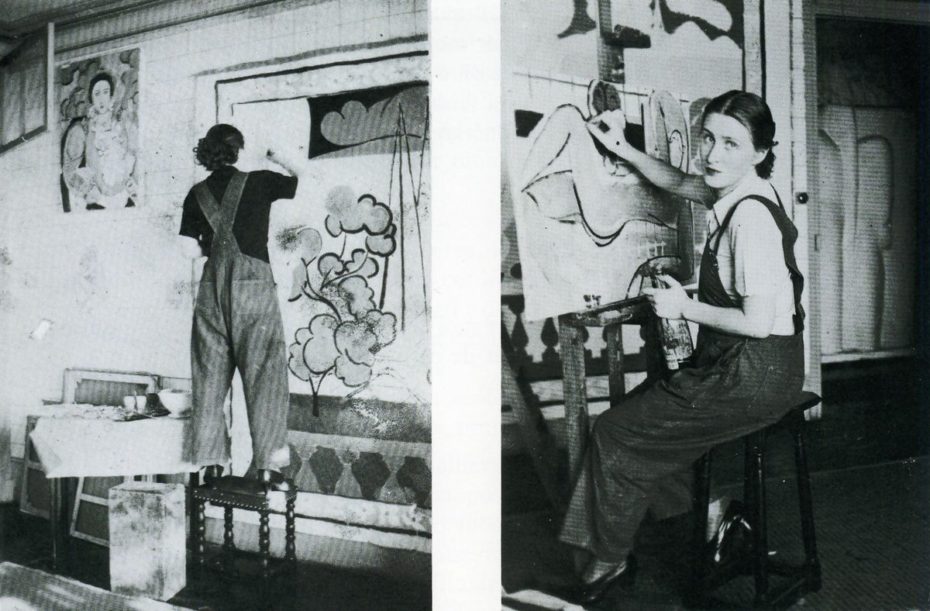

On the Côte d’Azur, her blonde hair and blue eyes ensured she got work as an artist’s model and dancer, and also as an extra in the burgeoning film industry at the local Victorine Studios. Still, she was barely scraping together a living and was mistreated by employers with wandering hands. At the height of the Années folles, Matisse was living in Nice, alongside characters like F Scott Fitzgerald, Edith Piaf, and Josephine Baker who wintered on the Riviera as he painted his models in the Rococo salon of the Hôtel de la Mediterranée. He had a reputation for treating his models respectfully, but when he met Lydia, he wasn’t looking for a new muse. His loyal wife, Amelie, was sick. She had always supported him in his career, but by 1930, her health was ailing and Lydia was offered a six month position to help run the Matisse studio as he finished his mural, The Dance II, which had been commissioned by American art collector Albert C. Barnes. When the employment ended, Matisse gave her 500 Francs to help get herself on her feet, but upon discovering that her lover quickly gambled the sum away at the casinos, leaving her with nothing, the artist rehired her as a nurse for his bedridden wife, Amélie – a role she undertook for three years.

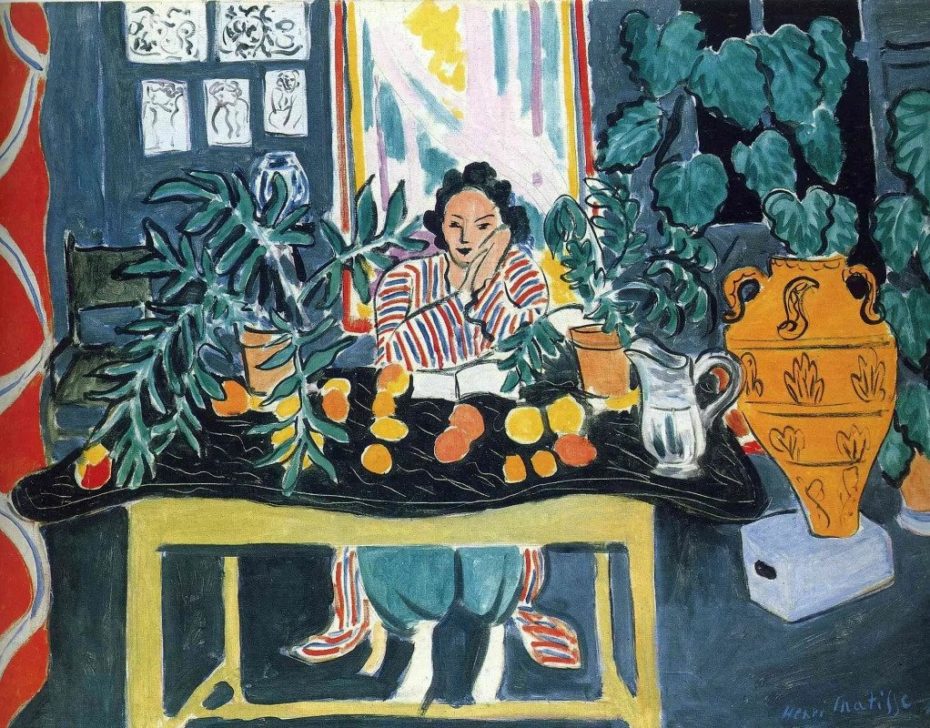

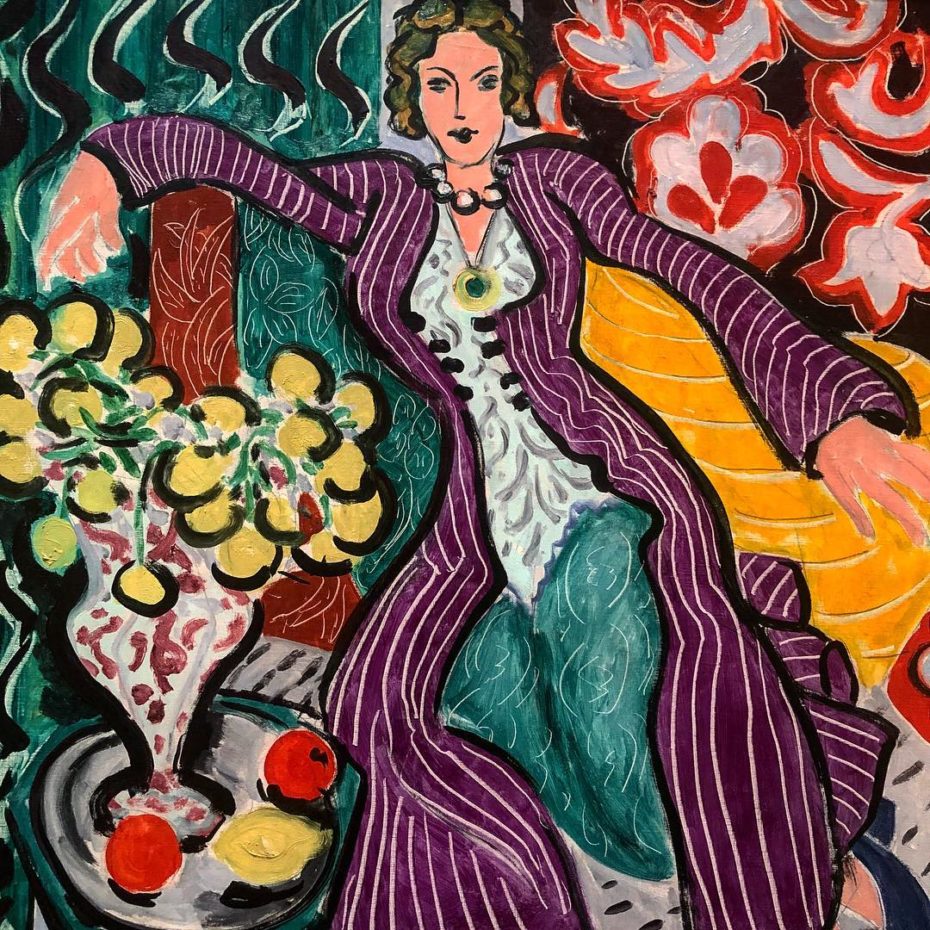

It wasn’t until 1935, that Lydia first modelled for Matisse. “After several months or perhaps a year, Matisse’s grim and penetrating stare began focusing on me”, Delectorskaya later recalled. “With the exception of his daughter, most of the models who had inspired him, were southern [Mediterranean] types. But I was a blonde, very blonde,” “Then, one day, he sat down with a sketchbook under his arm and, while I was scarcely paying attention to the conversation, suddenly spoke to me, ‘Don’t move!’ … And soon, Matisse asked me to pose for him.”

Unlike other artists she had known, he did not make advances, and she later reflected: “Gradually I began to adapt and feel less ‘shackled’ … In the end, I even began to take an interest in his work.”

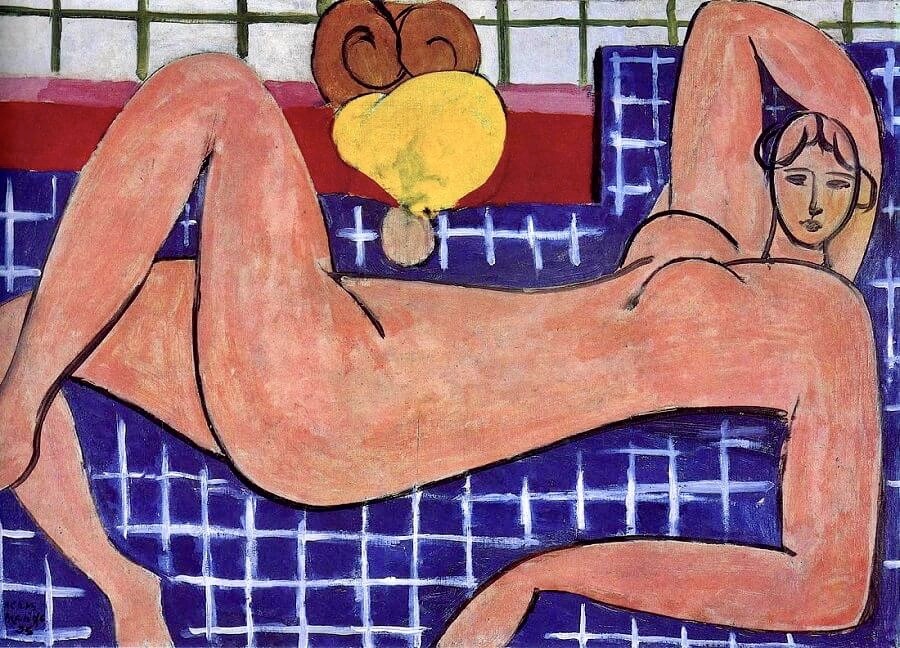

This “ice princess”, as he thought of her, was very different from his preferred dark-haired, olive-skinned subjects, but as Matisse’s biographer, Hilary Spurling notes, he was far too committed to his work to waste time and energy having sex with his models. “If Matisse made love to Lydia, it was on canvas,” she wrote in her book, Matisse The Master. The first painting Matisse made of Lydia was Large Reclining Nude.

According to the artist’s son Pierre, a successful art dealer in New York, his father had “renewed himself as a painter” with this work. Matisse’s wife however, who had initially welcomed Lydia’s presence, soon grew suspicious and resentful of their bond however.

Over the next four years, Lydia became Matisse’s only model, but she wasn’t just a pretty face and the hired help. Hilary Spurling interviewed Lydia several times and determined that “she could have run an army, she had amazing capacities. She ran the studio, she organised the models, she dealt with the dealers, sales people, the gallery … everything worked like clockwork.” She had become a creative partner, taking over the role that had been Amélie’s for decades.

“Madame (Matisse) wanted me to leave, not from female jealousy – there was no question of adultery – but because I was running the whole house,” Lydia later revealed. It was this loss of control that ultimately drove Amélie to give her husband an ultimatum, threatening to end their 40-year marriage if the young Russian was not dismissed. Matisse chose his wife. Ousted, Lydia attempted suicide, shooting herself in the chest, feeling that she had lost her purpose in life. Miraculously, the bullet was deflected by her breastbone and she survived.

In 1939, Madame Matisse left Henri anyway and Lydia was invited to her master, whom she would work with for the rest of his life, through wartime and illness. Along with one of his portraits of her, Matisse wrote: “To Lydia, who has no wings, but she certainly deserves them. Softness and kindness. As a sign of respect!”

When he underwent an operation following a diagnosis of cancer in 1941, the artist was able to produce some of his most famous works – paper cut outs and the Chapelle du Rosaire in Vence, for which he is now perhaps most remembered – thanks to the assistance of Lydia.

“You want to know, whether I was Matisse’s ‘wife’. Both no and yes. In the material, physical sense of the word — no, but in the spiritual sense — even more than yes. For 20 years, I was ‘the light for his eyes’, and he was the only meaning of my life,” wrote Lydia about her relationship with the artist.

Matisse died at the age of 84 in 1954, the day after making his last portrait of her using a ball-point pen. Lydia knew wasn’t going to be invited to the funeral by his family, so she left immediately, packed her bags and left them to the funeral arrangements. She lived alone for the rest of her life, devoted to working with the artist’s heritage. As the main specialist in his ouevre, she helped organise Matisse exhibitions and the opening of a museum in his homeland in Le Cateau-Cambrésis. The 90 or so artworks Matisse bequeathed to her, she donated to the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg and the Pushkin Museum, Moscow. Decades later, she wrote two books about her experience of his life and work: Apparent Ease (1998) and Against Winds and Storms (1996). Lydia committed suicide at the age of 84. Her last will was a note that read: “Please put Henri Matisse’s shirt next to me”.