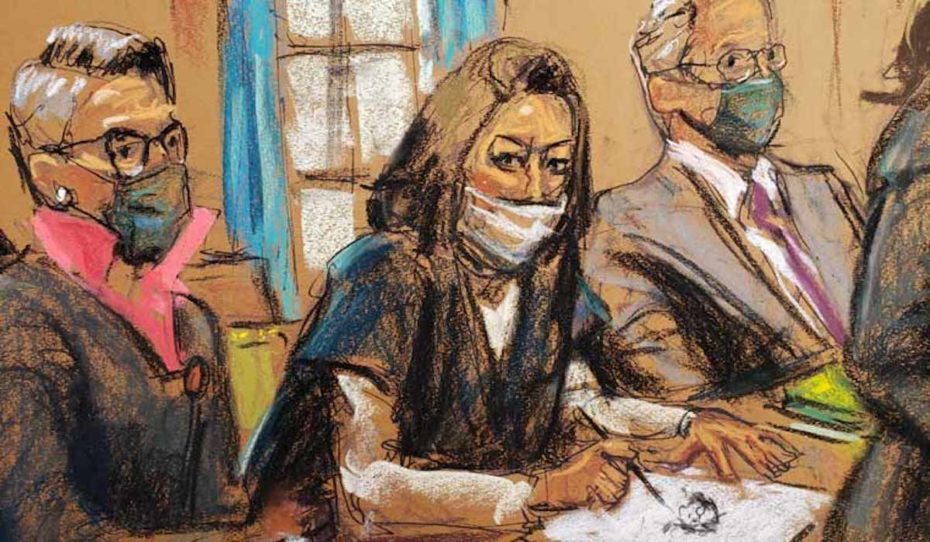

As 2021 came to a close, British socialite Ghislaine Maxwell was convicted on charges of sex-trafficking in connection with her former partner and accomplice, Jeffrey Epstein. However, it wasn’t her misconduct or the salacious details of her lifestyle that went viral, but rather a courtroom sketch … of Maxwell sketching the sketch artist back. The surreal image got us thinking about this overlooked and niche art form that has existed since before photography and persisted in spite of photographic innovation.

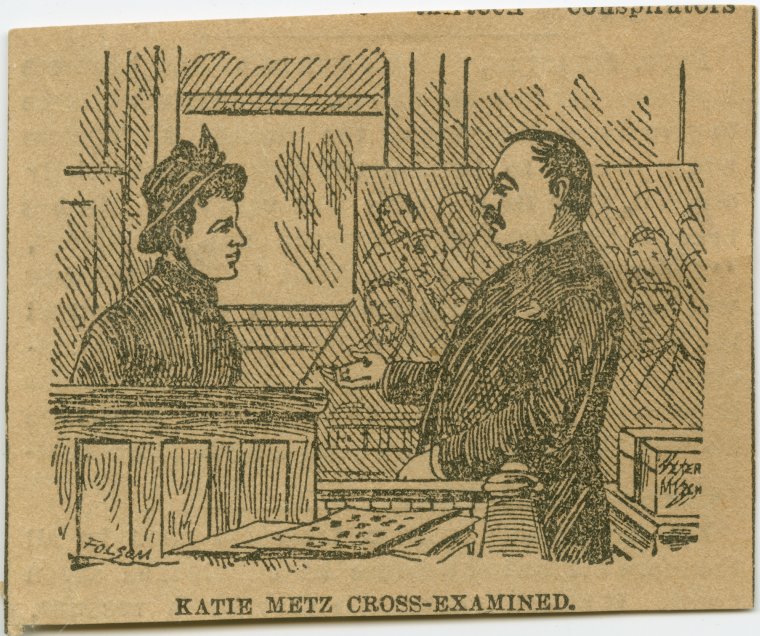

Artists have had a presence in our courts of law as early as the 16th century during the Reformation. An unknown English artist depicted a scene of the trial of Mary, Queen of Scots as she entered the courtroom of Fatheringay Castle in 1586 and Joseph Nicolas Robert-Fleury’s depiction of the trial of Galileo Galilei in 1633 hangs in the Louvre. In the United States, the history of courtroom sketching dates back to the Salem Witch Trials, while Victorian illustrators became crucial to the media. According to researchers at Syracuse University, “Victorian newspapers and news magazines had ‘artist firemen’ who were dispatched to the front to surreptitiously send back thumbnail sketches of the action”.

Contemporary artists of today can sell their sketches per sheet, or on a per diem commission, to TV stations, newspapers, or the subjects themselves, and several sketches have been acquired by institutional archives for their historical value, as well. The Library of Congress keeps its own collections of courtroom sketches.

Jane Rosenberg, the artist of the Ghislaine Maxwell courtroom document, says that sometimes, her subjects offer unsolicited feedback, like the hostility of sketching her back, above. “John Gotti wanted his double chin removed,” she told the New York Post. And they “always want more hair. I get that all the time.” It took Rosenberg a while to find her niche. She wasn’t sure she was fast enough with her hands, but she built a portfolio hanging around courthouses and drawing sex workers in night court until she sold a sketch to NBC. Since then, she’s had more work than she can handle.

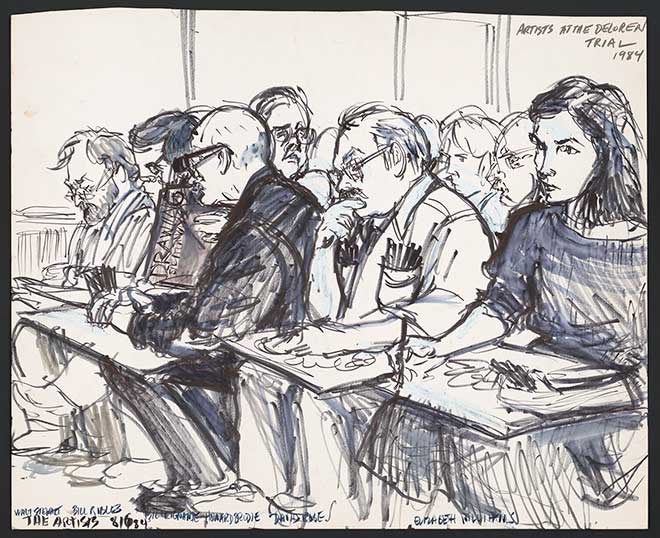

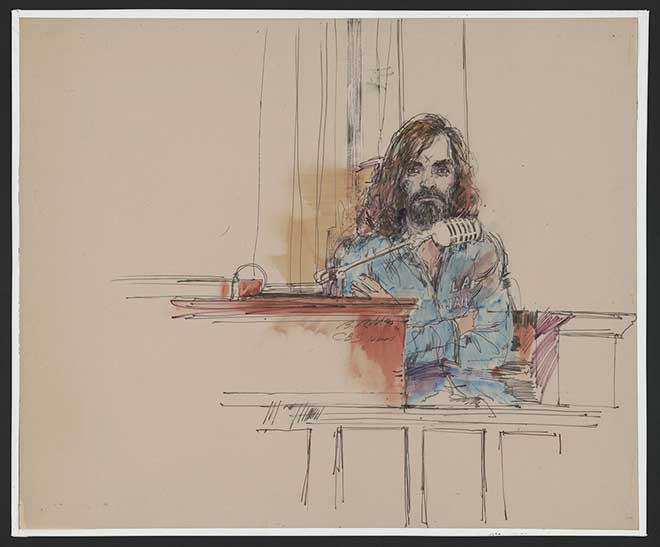

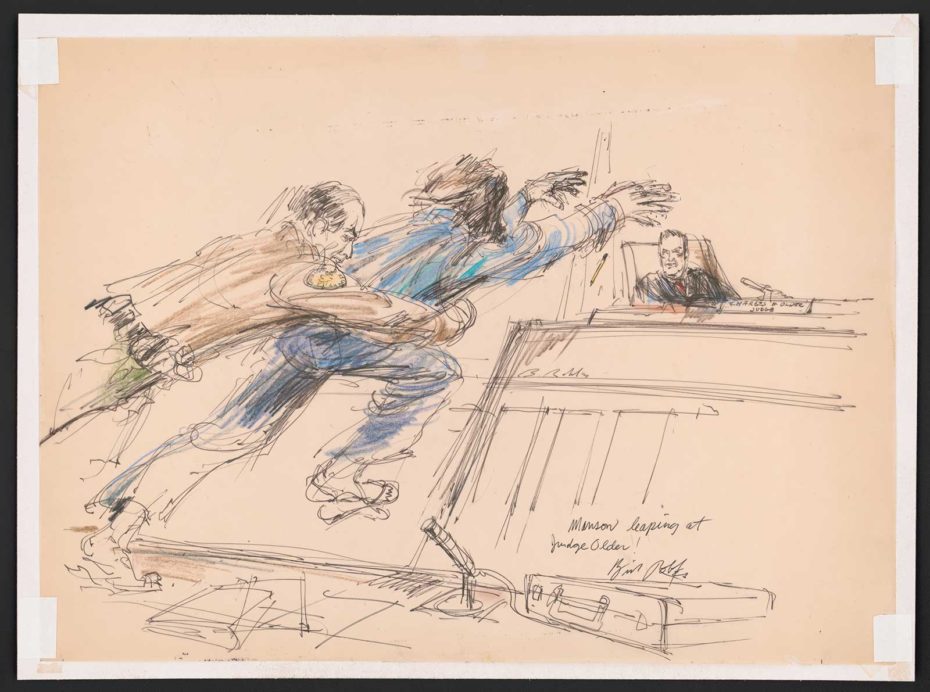

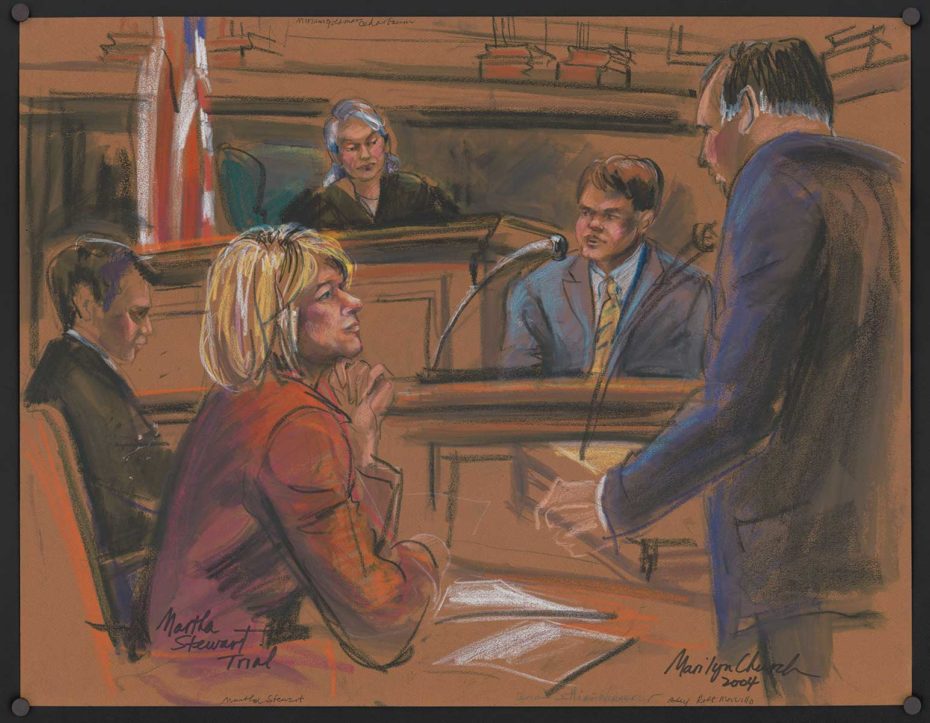

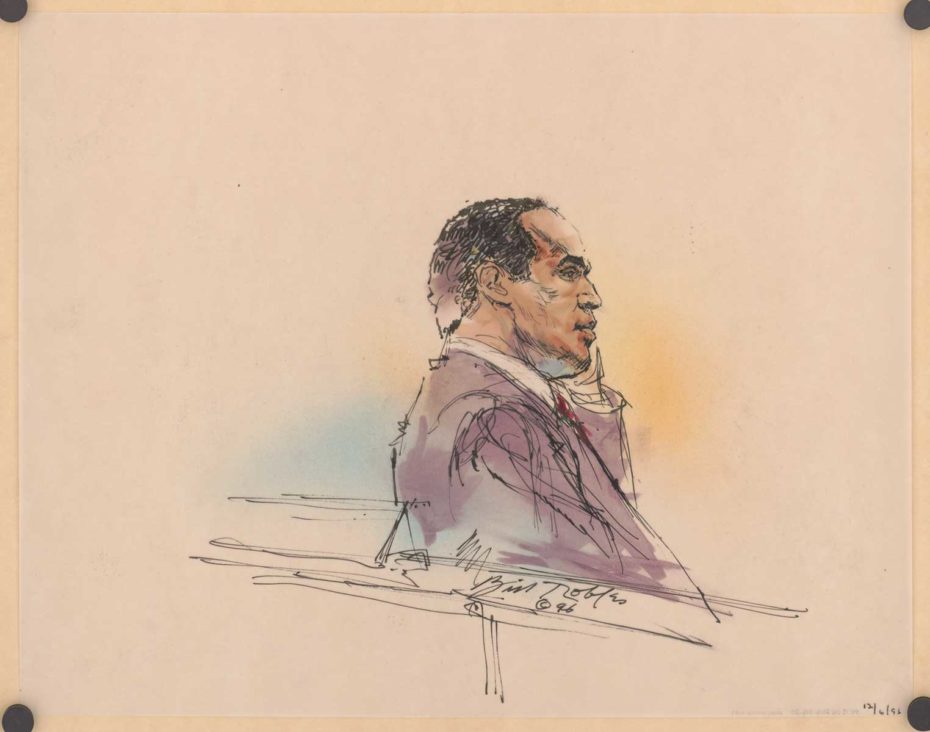

Several artists earned fame from courtroom sketches, such as Howard Brodie who famously illustrated cases included the trials of Charles Manson, Patty Hearst, and the Chicago Seven. Marilyn Church sketched the Son of Sam trial, and endured a similar staring contest with the defendant as Jane Rosenberg did with her subject. She also illustrated the high-profile trials of John Hinckley, Woody Allen, Martha Stewart, Leona Helmsley, Jackie Kennedy, Donald Trump, and the “Preppy Killer” Robert Chambers. Emmy Award-nominated Bill Robles first courtroom sketch was of the trial of Charles Manson, but he also covered those of O.J. Simpson, Ted Kaczynski, Timothy McVeigh, Richard Ramirez, Rodney King, and Michael Jackson.

For some trials, courtroom sketches are the only images the public ever sees. Photography in courtrooms has been banned since 1935, following the infamous media circus that surrounded the Lindbergh baby’s kidnapping trial. In 1944, Rule 53 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure was enforced, prohibiting photographing and broadcasting inside a courtroom. Still, anxiety about job security is a feature of the industry. “Since I became a courtroom artist, I’ve always thought cameras are going to be in court any minute,” Rosenberg revealed. “And they did pass a bill in 1988 to allow cameras [in New York state courts], and I thought, ‘That’s it. It’s all over for me.’ However, it didn’t hold true in all New York state cases.” One courtroom artist, Christine Cornell, says that the whole front of the courtroom used to be full of sketch artists. The legalization of courtroom photography for New York State in 1988, she says, eviscerated the industry. “Now, there are just a few of us. The industry changed, but there’s still crime.”

Some federal courtrooms experimented with cameras from 1991 to 1994. In the U.S. courts, many famous trials (like the O.J. Simpson murder trial) were televised. During the 1995 OJ Simpson trial, the ABC, NBC and CBS networks nightly news broadcasts gave more air time to the details of that case than to the Bosnian War and the Oklahoma City bombing combined. Nearly 150 million people watched the live verdict as O.J. Simpson was found not guilty. In response, many judges took the decision to once again ban the presence of cameras in their courtrooms, making it the primary reason news media often relies on sketch artists for visual depictions of the proceedings.

In many jurisdictions, cameras are prohibited because they are distracting, and they potentially violate privacy of those in attendance. Privacy can be observed through sketching by leaving their faces blank: “Rosenberg’s illustrations of the Maxwell trial and other cases include poignant portraits of anonymous witnesses with ghostly, blank faces.”

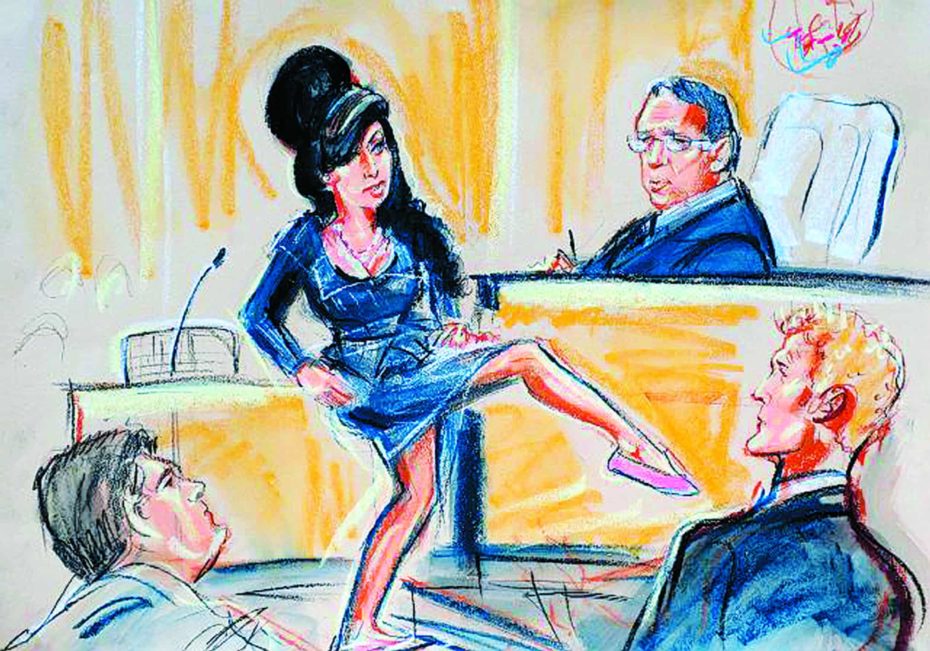

In some courts, including the United Kingdom and Hong Kong, artists are not even permitted to sketch proceedings while in court. Rather, they create sketches from memory or notes after leaving the courtroom. But even if they are allowed to sketch in the moment, artists have to be quick. They have to work especially fast during arraignment hearings where a witness may appear for only a few minutes – nobody is there to pose for them. And as if the time pressure isn’t challenging enough, often courtrooms are so crowded, the artists can hardly see the person they’re meant to be drawing. If they’re lucky, the trial has no jury and the judge may allow the artists to sit in the jury box, but most of the time, they’ll be seated in the public area with everyone else. Imagine Da Vinci trying to paint the Mona Lisa and capture her famous expression from behind! Courtroom artists need to be extremely good at capturing a person’s face from quick glances.

Reporting on the Maxwell trial, the Guardian’s J Oliver Conroy notes that hand-drawn art is more forgiving than photography, and potentially less lurid. A photo or still of someone’s expression can often be taken out of context. But “it also has the advantage of artistic license – artists can compress people and action into a single frame, conveying a sense of courtroom drama and atmosphere that is difficult for still photography to capture.”

Despite all the skill required of a courtroom artist, their work, at least to our knowledge, has never been associated with the fine arts world. Considered more dying craft than art form, we’d argue however, that for all the drama, the history in the making and the iconic subjects involved in its creation, the courtroom sketch deserves a more collectible status. For now, the niche has its own Instagram account.