Georges Méliès was an illusionist, in every sense of the word; a man who revolutionised cinema forever. He played an indispensable role with his innovations, creating the world’s first film studio, the first fictional film and when it comes to the invention of special effects in cinema, he’s the guy to thank. Yet, unlike other famous Parisian pioneers of the arts, his footsteps are notoriously difficult to trace in the city. Remnants from the forgotten filmmaker’s life were almost impossible to see before 2021, ignored by museums and historians alike. Nevertheless, Méliès’ story deserves to be known and remembered. So, in honour of the father of the seventh art, on the 160th anniversary of his birth, let’s take a tour around Méliès’ Paris.

Born in 1861, Georges was the son of a luxury shoe factory director. His family lived in a small house located at 29 Boulevard Saint-Martin. There is nothing particularly remarkable about the building today, in fact, it would almost go unnoticed if a heritage sign did not indicate the significance of the location. Growing up, he was expected to join the family boot-making business, but during his school days, Georges’ notebooks and textbooks were covered with drawings, portraits or caricatures of his professors and classmates. Despite his father refusing to financially support his budding passion for the arts, the future filmmaker spent his evenings as a young man frequenting various theatrical spectacles, in particular at illusionist shows.

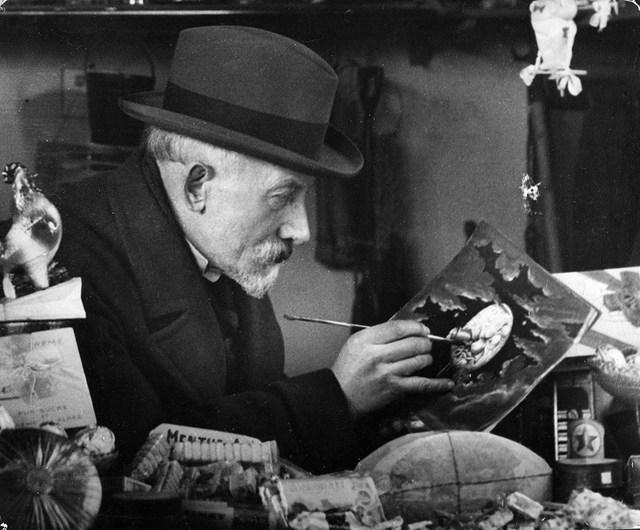

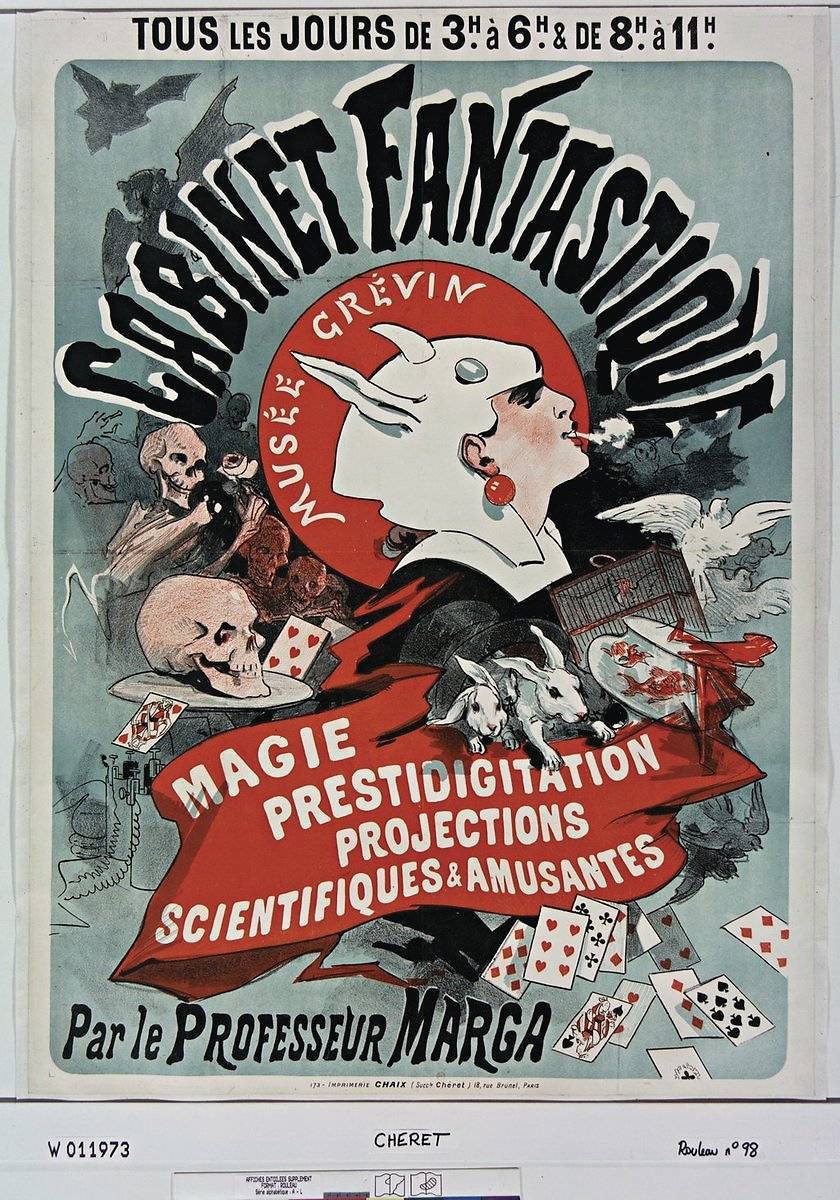

By day, he joined his brothers in supervising the machinery at the shoe factory, where he also learned to sew and acquired mechanical knowledge. And by night, he was an illusionist in the making. He eventually started making a living as a stage magician with revues such as the Cabinet Fantastique at the Musée Grevin, as well as a magic theatre inside the passages of the Galerie Vivienne.

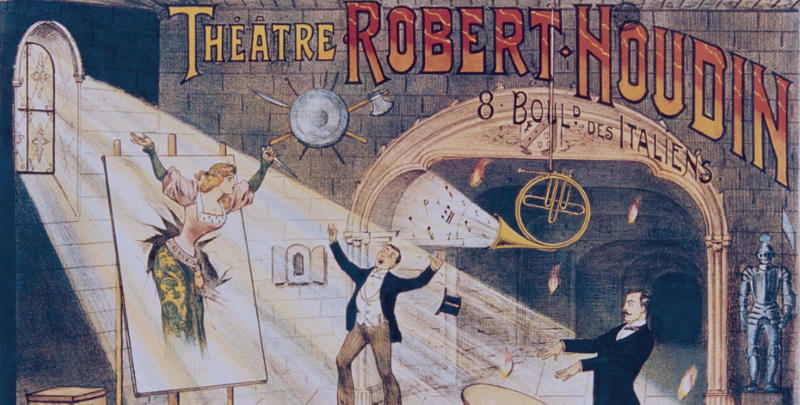

In 1885, he married Eugénie Genin, a wealthy orphaned heiress and soon after, he sold his shares in the family shoe business. The money was used to take over the management of the Robert-Houdin Theatre, at 8 Boulevard des Italiens, where he put on his own spectacularly innovative illusions with original scenery and costumed characters.

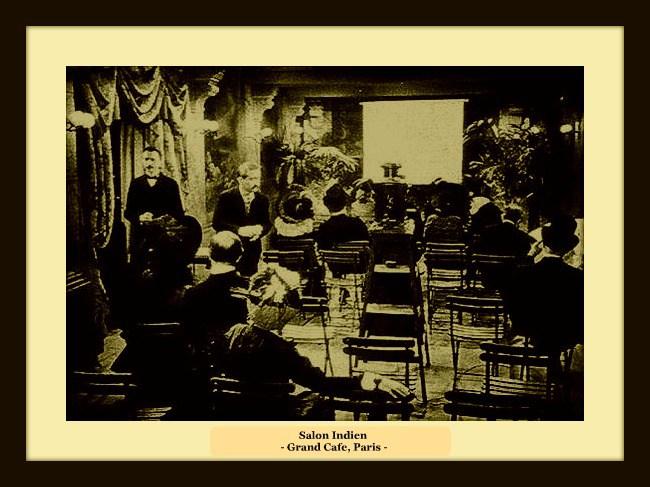

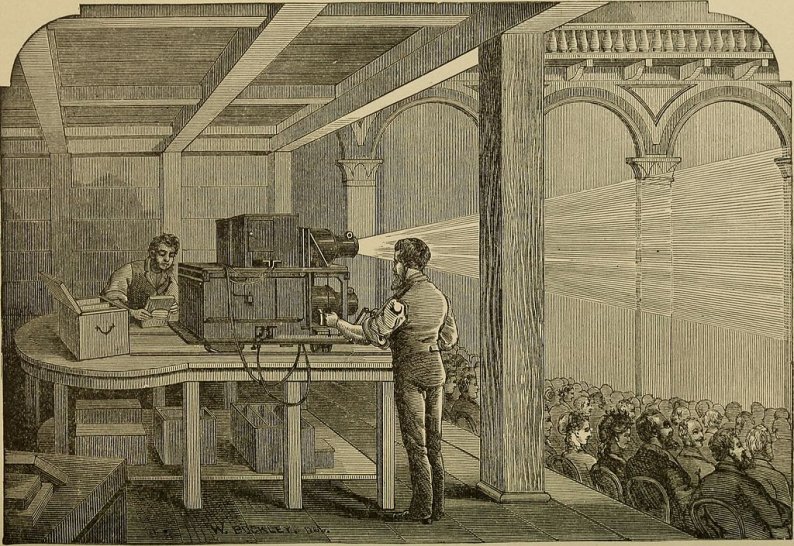

His shows were an instant hit and for a while, Georges was satisfied with life as a performer. But then, one fateful day in December of 1895, he found himself in the basement salon of the Grand Café near the Place de l’Opéra to see the first-ever public screening of a “moving image”. His friend Antoine Lumière, the father of the inventors, had invited him…

Ten short films were screened at the Salon Indien du Grand Café, where Méliès became awestruck and glimpsed the possibilities that the machine could provide for his own work. The very room that can be credited as the birthplace of cinema is now a restaurant inside the Hotel Scribe, called Rivages, a name inspired by one of the short films shown that day in 1895.

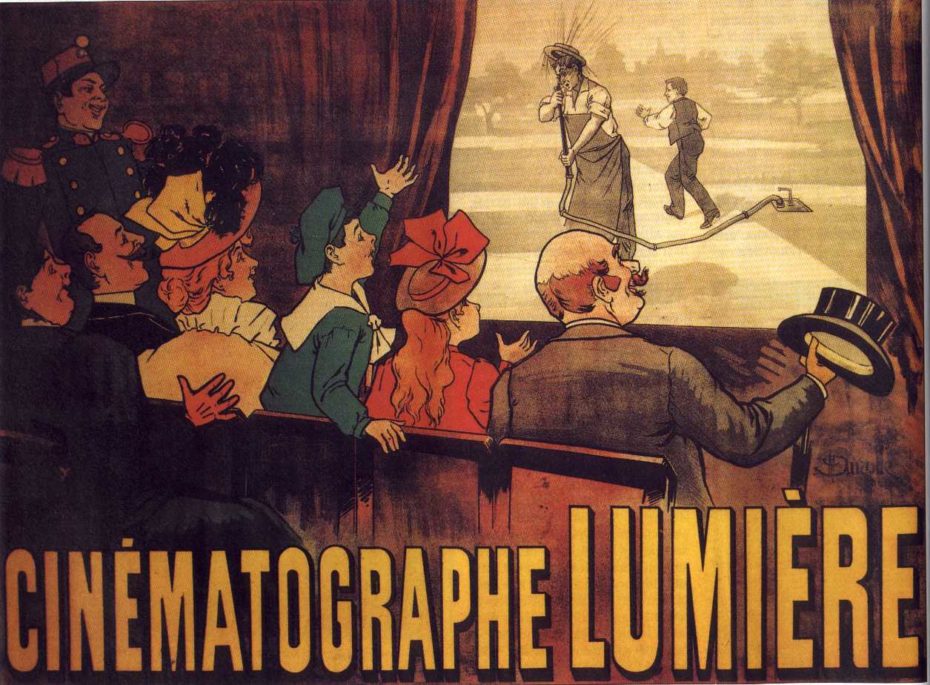

Georges immediately tried to convince the brothers to sell him a Cinématographe, and made a generous offer, but was refused. “This device, a simple scientific curiosity, has no commercial future!”, said the eldest brother, Auguste. In reality, the brothers were careful to keep a close control on their invention. Undeterred, Méliès travelled to London to buy the next best thing, an animatograph film projector, and re-engineered it himself to create his own film camera. Within a year of the Lumière screening, when moving pictures were still an emerging novelty, he added film projection to his theatre’s repertoire and even began making his own films to show there and sell elsewhere.

Georges’ first works, made between 1896 and 1900, are devoted to Paris and everyday outdoor scenes, like the Grands Boulevards, the Champs-Élysées, the Champ de Mars, and the Eiffel Tower. Unfortunately, all of these early films have been lost. But during his phase of experimentation, one day, his camera’s crank got stuck while filming a street scene. After Méliès repaired it and continued shooting, he later realized that the capture of a bus which had been passing by before, suddenly turned into a different vehicle, like a magic trick. “A Madeleine-Bastille bus changed into a hearse and women changed into men. The substitution trick, called the stop trick, had been discovered,” he wrote in his memoires. Méliès decided to use cinema and its spectacular theatrical capabilities to produce the firsts fictional movies under his new company Star Films.

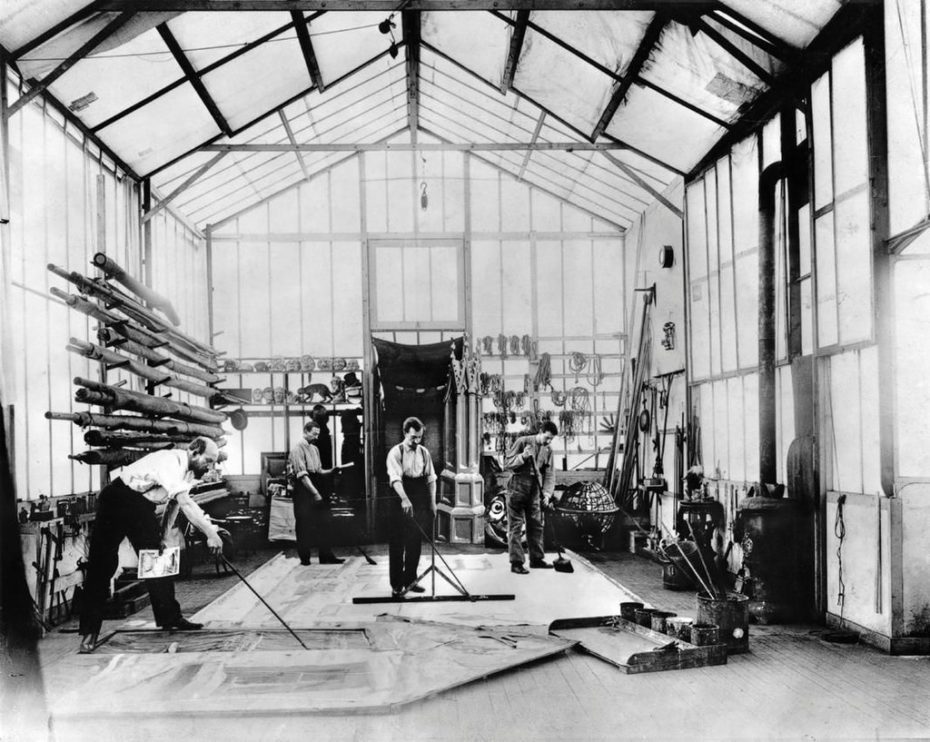

He incorporated many of the tricks he had developed on stage, creating disappearances, exploding heads, bodies that duplicated themselves, and other complex special effects with precision. He dedicated himself to these fictional works and ran a small photography studio in the back garden of his family’s property in Montreuil-sous-Bois. The glass roof greenhouse became the first film studio in the history of cinema.

Méliès explored different genres in his productions. “Le Manoir du Diable” (1896) and “Le Caverna Maudite” (1898) are considered to be the first horror movies ever made, while “Le Voyage dans la Lune” (1902) is the first science fiction film. The latter, his most famous work, took several months to make and required a considerably big budget. The scene in which the spaceship hits the Moon’s eye would go on to become one of the most iconic images in cinematic history. It was based Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon and The First Men in the Moon, by H.G. Wells. In the end, screenings were an immense success and over 500 copies were sold. The acclaim came with a price, however, and the film soon faced a piracy problem in the United States that prompted Georges to send his brother Gaston over to New York to combat American counterfeiters.

After a period of great recognition came Méliès’ downfall. Several of his movies failed commercially, in part due to turmoil of World War One in France, but also because he couldn’t keep up with the demand as major American production companies cranked out hundreds of films a year. A fairground trade journal quoted Méliès as saying, “I am not a corporation; I am an independent producer.” Bankrupt, at the age of 52, he ended his career as a filmmaker. Around that same time, in 1913, Georges’ wife died and he was left alone to raise their two sons, Georgette and André. In 1917, the French army turned Méliès’ abandoned studio in the Parisian suburbs into a hospital for wounded soldiers. They also confiscated over 400 of original celluloids and melted them down to make heels for the soldiers’ shoes. Georges was so angry he burned all of the negatives that were left, as well as most of the sets and costumes. Yet another loss came when his beloved Robert-Houdin theatre, which he was still managing, was torn down in 1923 for the renovation of Boulevard Haussmann.

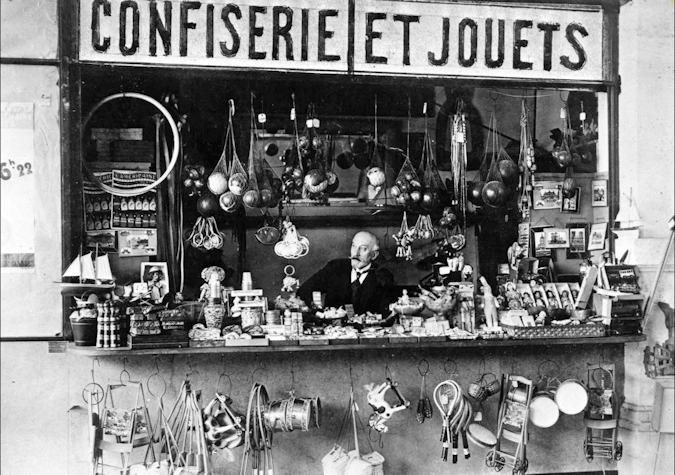

As the Lumières had predicted, he became financially ruined and his legacy ended up falling into oblivion. To be able to survive, he opened up a stall in the main hall of the old Gare Montparnasse, selling candy and toys with his second wife, Jehanne d’Alcy (known as Fanny), a former lead actress in many of his films.

The 2011 Martin Scorcese film, Hugo, is packed with sumptuous visuals from a 1930s city of light, but the film is also an ode to the re-discovered legend of cinematic history. True to life, we find Méliès, forgotten and broken, destined to make a meagre living as a candy and toy salesman at the Montparnasse station in Paris, until he meets a young and curious orphan by the name of Hugo.

It was in the toy shop that Léon Druhot, editor-in-chief of the magazine Ciné-Journal, found Georges in 1929. He commissioned a memoir from him to demonstrate his importance to the film industry and subsequently lifted him out of anonymity. Recognition came again in 1931, when Georges was awarded the Legion of Honour. But the artist still lived in poverty. This was addressed when the following year, the Cinema Society put him in a retirement home for film veterans at the Château d’Orly. Meanwhile, Méliès became the honorary president of the Cinémathèque française, founded by Henri Langlois, from 1936 until he died on January 21, 1938 due to cancer. He was buried in division 64 of the Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Méliès’ final resting place fell into a state of disrepair until his descendants started a crowdfunding campaign in 2019 to restore the tomb. The fundraiser was successful and allowed the grave to be properly restored as well as protected for the coming decades.

Despite so much of his work being lost, there was one man who tried to rescue what was left of Georges’ legacy. The late Henri Langlois, a passionate cinephile and archivist had acquired one of the largest cinematic collections in the world by the beginning of World War II, only to have it nearly wiped out by the German authorities in occupied France, who ordered the destruction of all films made prior to 1937. He and his friends smuggled huge numbers of documents and films out of occupied France to protect them until the end of the war.

Henri had had the opportunity to meet Georges while he was still alive, and spent years collecting his machines, costumes, drawings, models, posters, and surviving movie reels, assisted by the filmmaker’s granddaughter Madeleine, as well as donations from Georges’ second wife. Langlois managed to gather an impressive treasure trove of Meliès items which is now exhibited at the Musée de la Cinémathèque in the 12th arrondissement.

The new museum takes us on a journey through the history of cinema, from Paris to Hollywood, and pays homage to Méliès, the first magician of cinema. In the collection are Méliès’ camera, 150 photographs, and the cape he used to wear when performing, as well as props from the many films Georges helped inspire, including an automaton from Scorsese’s Hugo, the robot from Metropolis (1927), a car from Blade Runner (1982), a sculpture from Alien (1979), costumes from The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), and original storyboards from Star Wars. A visit to the Cinémathèque serves as a reminder of just how of big a mark Méliès left on contemporary cinema.

Special effects techniques as we know them today, such as crossfades, animated models, optical effects, color effects and many more, were applied for the first time, with no previous technique, by the conjurer, producer, distributor, director of photography, screenwriter, actor, decorator and costume designer that was Georges.

And though he died impoverished and arguably betrayed by the industry he helped build, today we can appreciate his genius by watching the few films that have been preserved, ironically, due to the pirated and confiscated copies he fought so hard to destroy.