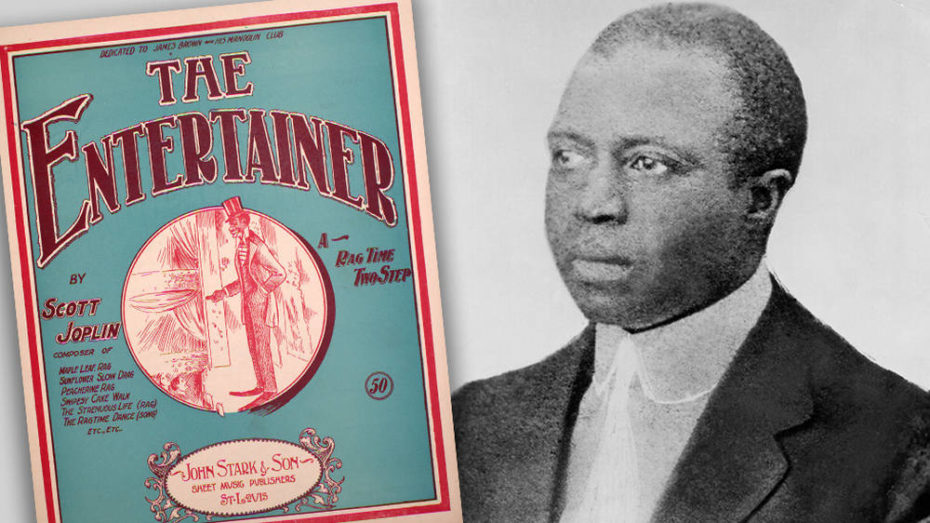

You know the sound of ragtime even if you don’t think you do. “The Entertainer“, a classic piano rag, is one of the most recognisable melodies of the 20th century (go on, have a quick listen). But it was written by America’s greatest musician that we’re betting you’ve never heard of – an African American composer by the name of Scott Joplin, who laid the cornerstones of what many of us would now think of as American music. In the beginning, before Jazz, there was the syncopated melodic march of Ragtime, and for a period, it would captivate a nation, sparking its first popular music craze in history. Gestating in the barrelhouses and saloons of the mid west, Ragtime would help create the music industry as we know it, produce its first stars, influence and shape American popular music, revolutionise the way we play classical instruments and divide cultural opinion, all before fading back into the cultural ether.

Ragtime began to evolve on the piano in the late 19th century and took its name from the act of experimenting with the rhythmic nuisances of a musical piece, the underlying beat in one hand and a syncopated melody in the other to produce a ‘ragged’ musical rhythm that made you want to move. What would emerge would be an intoxicating new genre of music. The sound of Ragtime was uniquely American, implanted in the multi-cultural landscape of a still relatively young country and cultivated by the African American pianists of the day. It would draw influences from African drumming, classical compositions, as well as the banjo and fiddle playing of the European immigrants flooding into America.

But ragtime found its footing in a more disturbing place – the minstrel show – a racist “comedic” performance of mostly white people in blackface, imitating African American music and dancing, which disappointingly, also happens to be the first original American theatrical form. The performing style emerged soon after Emancipation and marked the first instance of Black music passing into white society. Despite the great cost to their pride, African-American artists reluctantly made their way onto this controversial stage too, and in a bid to reach a wider white audience, Black-only minstrel groups formed and toured the country.

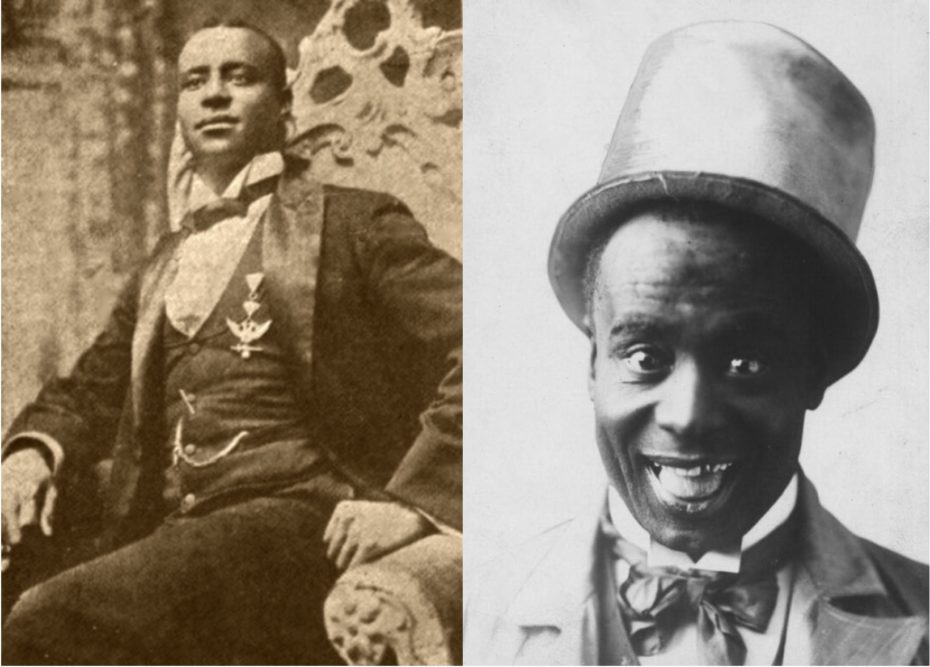

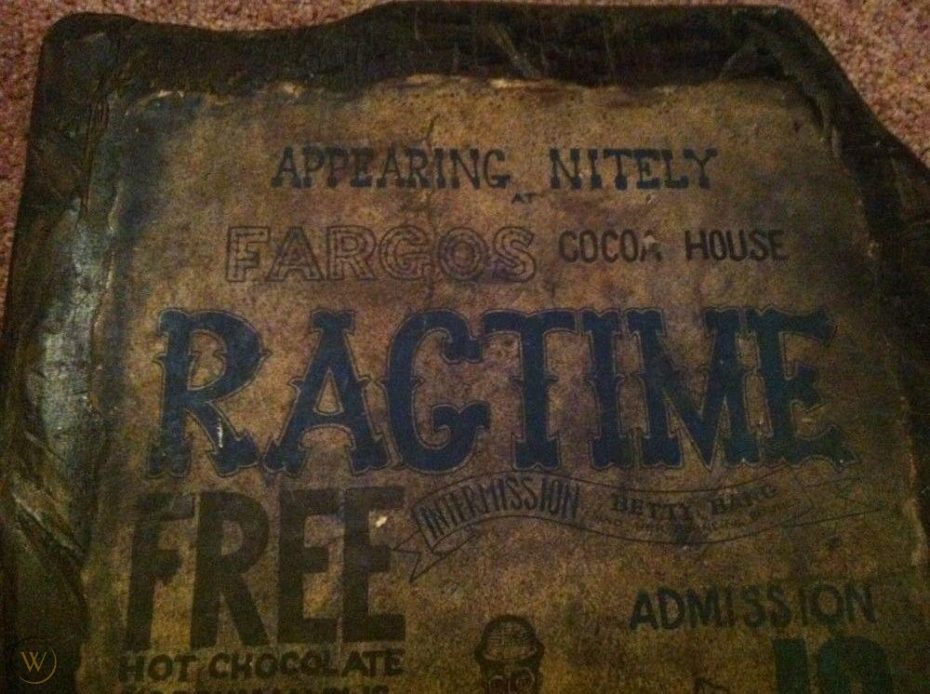

One such African American minstrel artist was Ernest Hogan, who may be credited as the first ragtime artist to be published. This new style of music had been evolving along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers of the Midwest for some time. Traveling African American pianists who worked the sporting houses, brothels and diners of small towns had started to develop polyrhythmic improvisations to the jigs and military marching music of the time. The patrons of these establishments were witnessing the new swirling up-tempo momentum of something brand new that was forging, and they couldn’t get enough. In 1895, the first recognized Ragtime song would be published, ‘La Pas Ma La’ by Ernest Hogan and his minstrel group the Georgia graduates. The composition was developed from a dance called the ‘Pasmala’. It had a stumbling staccato rhythm and an infectious melody, and it would open the door to what would become the first popular music of African American origin.

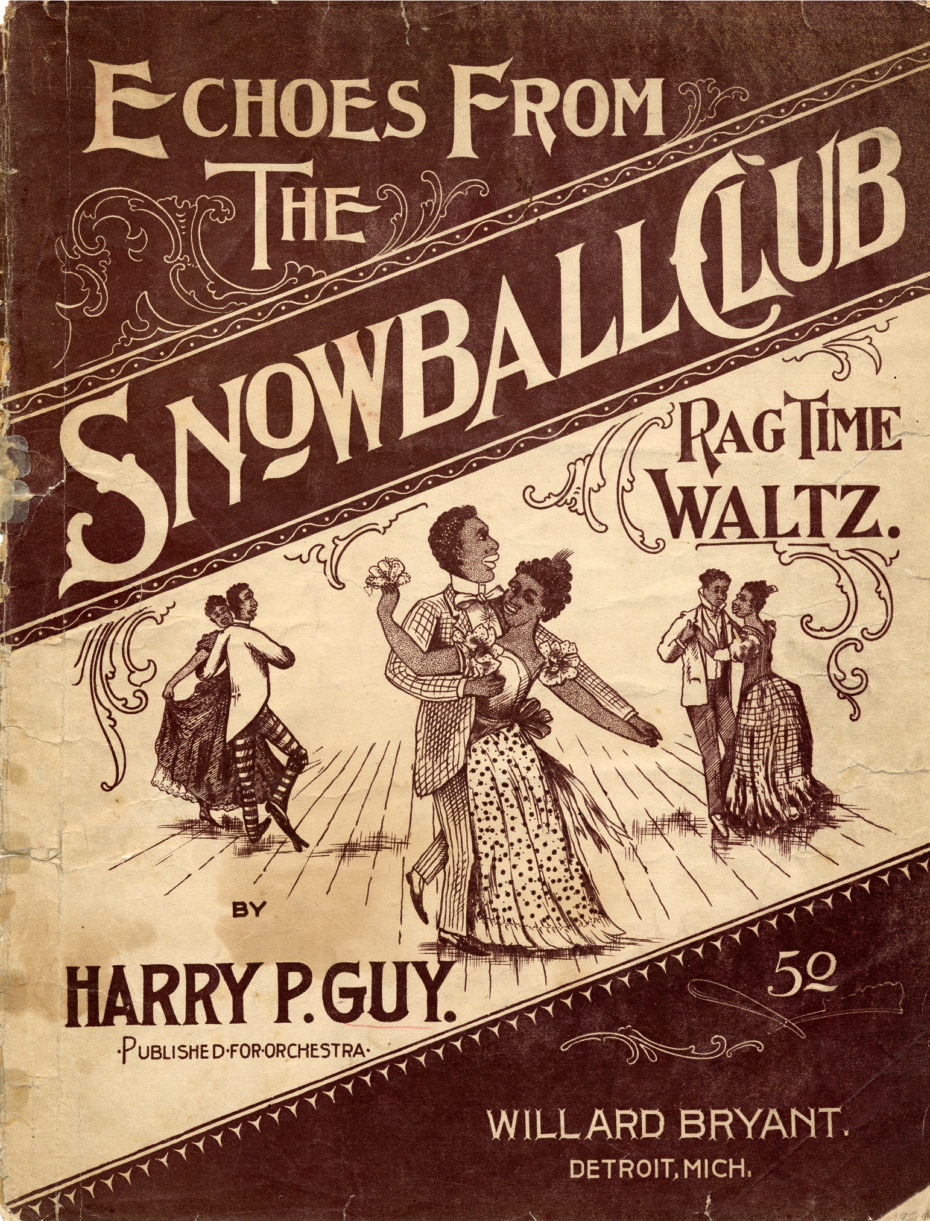

By 1877, Thomas Edison had invented the phonograph, but the recording industry was still yet to be born. The wax disc and the mass availability of records and amplification didn’t exist either, so music publishing was how revenue was generated in this period before the widespread availability of record players. Publishers would copy write and distribute sheet music to the public and musicians alike. (Sadly, so much of early ragtime sheet music features an overwhelming theme of racist blackface artwork).

Music was heard in halls, in bars, diners and parlours of the middle and upper classes. Later, the pneumatic player pianos or pianolas – the jukebox of the day – would become popular and have a brief moment in the spotlight. These seemingly magical wooden entities would help boost sales of the musical scores that were now being transcribed and transferred onto punctuated paper rolls.

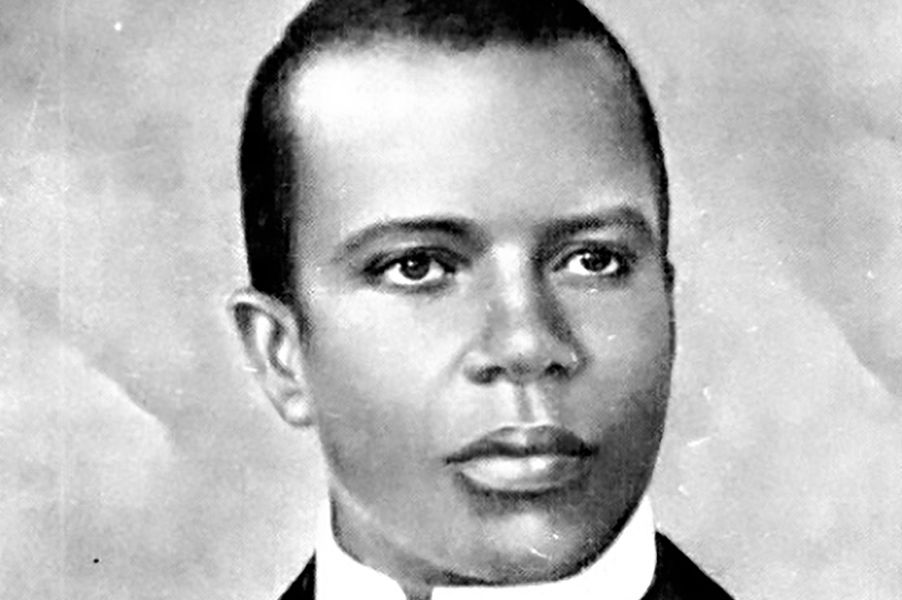

Then, in 1893, a cultural and social extravaganza would attract 27 million visitors over 5 months when Chicago held the world fair to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the New World. Many Black musicians and entertainers were not granted admission to perform inside, so a fringe event sprang up on the outskirts. Tents, stalls, cafés, and bars were erected and the soundtrack to this merriment would be Ragtime. Though not yet named as such, this was the first time the public would hear the new sound en masse, and the good times did roll. Musicians had flocked from all over the country for exposure and monetary gain; one of these would be legendary ‘King of Ragtime’ musician and composer Scott Joplin. The son of a former slave, born in Texas in 1867, as a child, his parents would come together in the evenings to play the banjo and violins for the family. Most of the affluent white-owned houses where his mother cleaned had pianos, giving Joplin a chance to play while she worked. His formal instruction would come from a Jewish, German-born classically trained pianist, a Mr. Julius Weiss who recognised the talent of Joplin and gave him free lessons.

He would eventually set out and become a popular travelling musician of the day, and in 1899 he composed ‘Maple Leaf Rag,’ around the same time that he met John Stillwell Stark, one the first and most successful publishers of ragtime in the country. This serendipitous encounter would prove to be instrumental in the fortunes of both men. After some initial doubt with the difficulty of the piece of music for the average parlour-playing maestro, Stark relented and published Maple Leaf, Joplin would become maybe the first musician to secure a royalty on music publishing, at 1% return.

The song would become their greatest success and make Joplin’s name synonyms with Ragtime. It wouldn’t be the first, but it certainly would be the most popular, eventually selling over 1 million copies. He’s said to be the first artist in history to sell that many copies of music in his lifetime. The public had tasted the elixir of this oscillating melodic beat and decided they wanted more. One newspaper critic wrote.

‘‘Suddenly I discovered my legs were in a condition of great excitement, they twitched as if charged with electricity and betrayed a considerable and rather dangerous desire to jerk from my seat. The rhythm of the music which seemed so unnatural at first was beginning to exert its influence over me.’’

Publishers began to churn out sheet music from newly signed artists; piano rolls were manufactured and talent contests organised as Ragtime rolled onwards, spreading over the United States. Patrons at dance halls and theatres would soon develop new styles of dances for the craze. There was the ‘Grizzly Bear’, ‘The Turkey Trot’, and ‘The Bunny Hug’, but most notably, this is where ‘The Foxtrot’ was born. Tin Pan Alley, once the beating heart of the budding American music industry in New York, cottoned on to the trend and publishers started to produce their own ragtime songs.

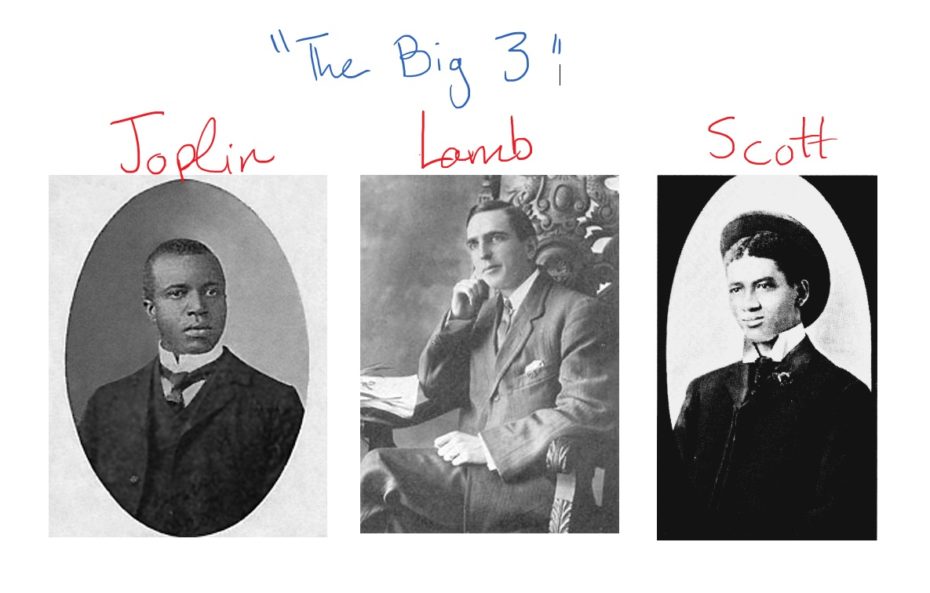

Over the next few years, other major stars of the genre would emerge on the scene. There was James Scott with his original compositions ‘A Summer Breeze’ and ‘The Fascinator’ both released in 1903. In 1906, he would meet his hero, Scott Joplin, who was so impressed with his writing and playing that he introduced him to John Stark, who would go on to publish Scott’s songs. He was known as an introverted show man, who struggled to make eye contact most of the time, but when performing, would bounce up and down on his stool wrapping his leg around the base to stop himself from being propelled into the air as he pounded on the keys.

The most improbable star of Ragtime would have to be Joseph Lamb; the New Jersey born Irishman who purchased some Scott Joplin sheet music and became captivated with the ‘new sound’. Practising to learn the syncopated rhythm he developed his playing and started composing his own ‘Rags’. On a shopping trip to Johns Stark’s music store in New York, he too ran into his musical idol, Scott Joplin. Ever the gregarious enthusiast for cultivating new talent, Joplin persuaded John Stark to publish Lamb’s songs. He would become an unlikely addition to the African American-led musical phenomenon and together, Joplin, Scott, and Joseph become known as the ‘Big 3’, the most popular and influential artists of Ragtime, arguably the first pop stars, who made it possible for the genre to become a music of lasting significance.

Like any art form that becomes wildly popular and has such an impact on society, there will be detractors. Critics and self-proclaimed righteous crusaders mounted their soapboxes with determined puritanical abandonment. The press ran stories about Ragtime eroding morals. One critic wrote, “Ragtime is syncopation gone mad and its victims in my opinion can be treated like a dog with rabies, namely with a dose of lead”. The anti-reformers and the evangelical brigade had been rattled. Their disdain for the sound undoubtedly had everything to do with race. Ragtime would be the first, but jazz too would suffer its own disparaging vilification, then Rock & Roll, all the way up to Hip Hop and rap. The similarities in the fear and insecurities of the detractors would echo on through the years but for now, Ragtime was reaching its peak.

Ragtime at the Zenith of its life had reached the far corners of Europe, had influenced classical composers like Igor Stravinsky, and Claude Debussy, had been enjoyed by King Edward VII, Wilhelm II, and the Czar of Russia. New music publishing houses sprang up, fortunes were made and lost, pianos sold in high numbers, and the public kept on dancing. And like anything that reaches its pinnacle, there must be a descent. The demand for Ragtime had been so high that publishers had swamped the market with lesser quality ‘Rags’. Tin Pan Alley had employed more writers just to keep up with demand and compositions had been put into two categories; that of ‘Rags’ and ‘Classic Rags’ to differentiate from the quality originals. Interest started to wain around 1917 when a new style of music was making its way onto the scene, an improvisational collaborative decedent of ragtime, which would soon be known as Jazz.

When the masses lost interest, the sheet music stopped being published, the player pianos were silenced and as quickly as it had caught on, it was over. It was 1920. Unlike other genres of music where a cross-over would occur and the lesser would still be on the peripheral consciousness of the public, Ragtime seemed to just implode.

And what of its stars? Scott Joplin, the ‘King Of Ragtime’, after an unsuccessful attempt to create a ragtime opera called Treemonisha, became bitter and despondent that he couldn’t find an audience in the classical world, which was unaccepting of his race or talent. By 1916, he was suffering from syphilis and put into a mental institution where he died penniless in 1917. He was buried outside the sanatorium in an unmarked grave.

James Scott would move to Kansas City and become a music teacher and organist at the local silent movie theatre. Joseph Lamb, the unlikely white star of ragtime would go back to selling textiles, only continuing to compose music as a hobby. In the 1950s, when music historians contacted him to talk about his influence on ragtime, they were quite shocked to discover he was white. John Stark, the most successful publisher that would come out of Ragtime, had attempted to keep the wheels turning on his publishing business, releasing old Rags from the archive, but eventually admitted defeat and closed shop. He would be remembered as a decent man who was fair towards his artists in a time when so many weren’t.

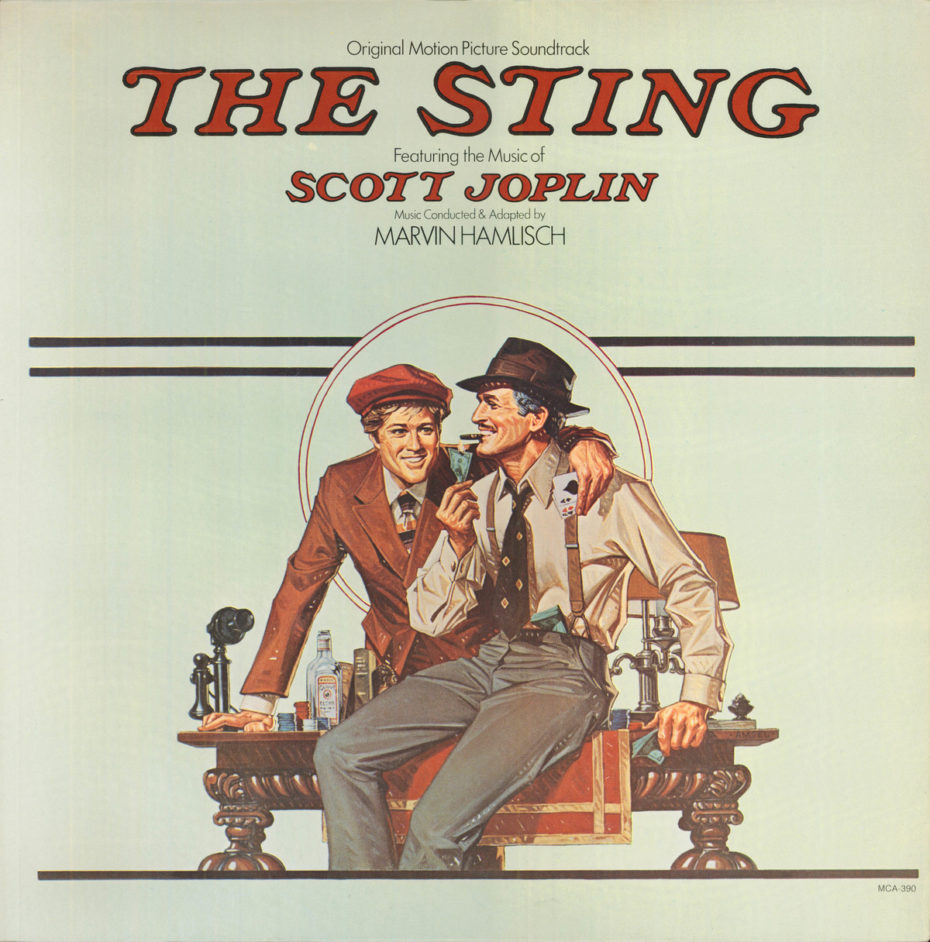

Ragtime would have a brief resurgence, or should we say “rediscovery” in the 1970s, starting with an album released by Joshua Rifkin ‘Piano Rags By Scott Joplin’ which would go on to be nominated for two Grammys. Then Joplin’s Opera Treemonisha would finally get the production it deserved with The Atlanta Symphony company in 1972. The 1974 film The Sting starring Robert Redford and Paul Newman would feature Joplin’s ‘The Entertainer’ as the main theme, and the film would go on to win an Oscar for best soundtrack.

Enthusiasts across a broad spectrum still keep this quintessentially American music alive at home and beyond with niche conventions, gatherings, gigs, and festivals, but nothing will compare with that brief time when it was everywhere and everything. Ragtime will remain the first step into what we now think of as popular music, not a furtive dalliance, but a rampaging syncopated stamp into what would come.