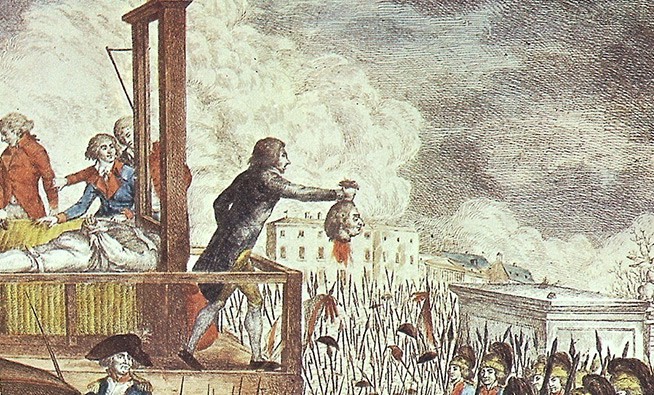

Those of us who paid any attention in history class can probably recount a few key details and players of the French Revolution – there was Marie Antoinette, Louis XVI (AKA Louis the Last) and their posse at Versailles who were eating too much cake; the revolutionaries who kicked things off by storming the Bastille prison; and an infamous Reign of Terror that ensued, starring the guillotine. Rarely however, do we mention the subculture that would emerge in the aftermath of it all, morphing into an outrageous public display of aristocratic grunge fashion. In what was essentially a ‘proto punk’ movement of the 18th century, visions of scruffily-clad aristocrats being carted off to the guillotine for public beheadings would launch an morbid tongue-in-cheek fashion trend for the survivors of the revolution. Long before the 20th century punks gave us studs and spiked Mohawks during the social unrest of the late Seventies, the post French Revolutionaries of 1793 gave us blood chokers, ripped corsets and cropped, tangled locks, all aimed at symbolising the horror of the guillotine and ridiculing the very foundations of the post-revolutionary society.

Les Incroyables (‘Incredible Men’) and Les Merveilleuses (‘Marvellous Women’) were the respective gender titles given to the proponents of a reactionary movement, led by many of those whose families or themselves had been subject to the treatment and trauma of a post-revolutionary regime. Under the radical new French government, the infamous Jacobin turned power-crazy politician, Maximilien Robespierre, sent thousands of aristocrats, royalists and political opponents to their deaths or to prison in the name of change. But by 1794, just five years after the infamous storming of the Bastille, a counter-revolutionary event occurred, in which Robespierre himself was deposed and executed the next day by his opponents. The number of executions dwindled over the coming months and during the Directoire period, France’s governing body between 1795 and 1799, the extremes of the revolution thawed, leaving the Incroyables and Merveilleuses to blossom.

These survivors of the old establishment suddenly felt safe again, and adopted a new behavioural trend that mocked guillotine mob humour and the frugality of post-revolutionary life in a radical yet anti-radical display. In the wake of their trauma and renewed sense of power and entitlement, many used exaggerated and exotic speech to attract attention, particularly common was dropping the letter ‘R’ in reference to the unspeakable revolution. The men, or the ‘Inc’oyables’, chose extravagant ill-fitting hats, oversized earrings, colourful cravats, huge neckties, long unkempt hair, bright coats and jackets, all suggestive of a last minute, ill thought-out dressing spree prior to that jolly ride to execution – a journey endured by so many of their peers.

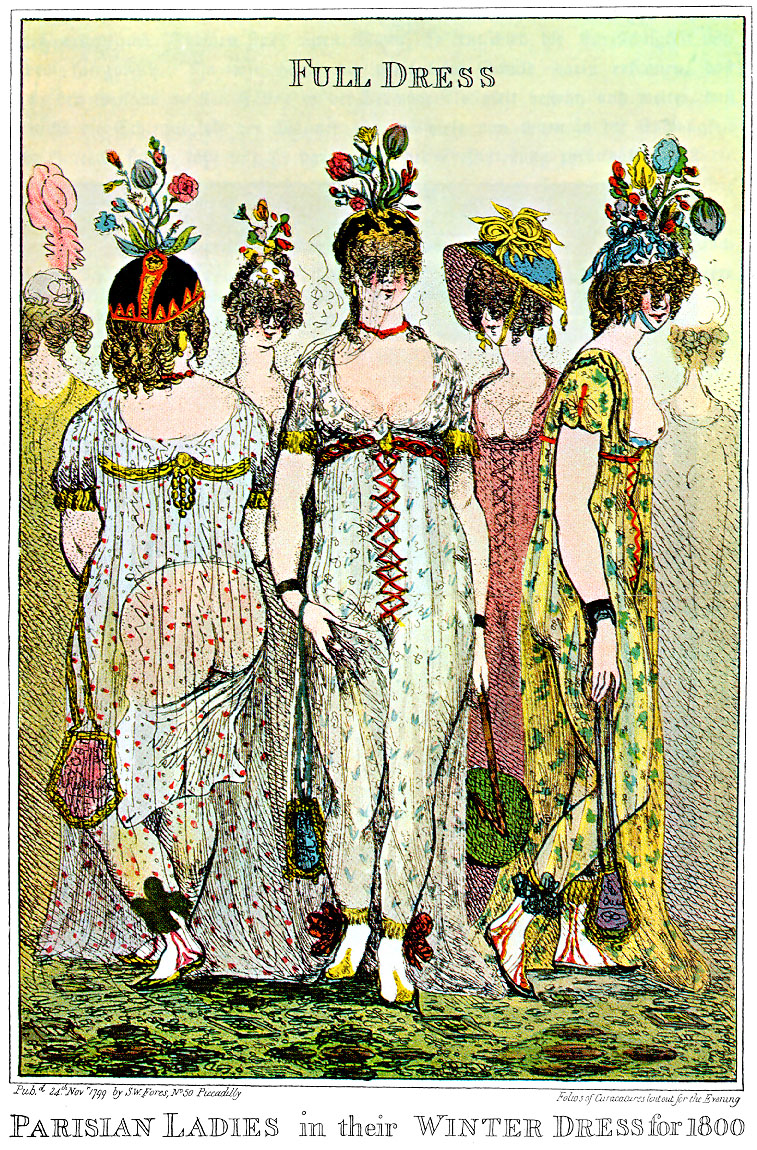

This was a very ‘bourgeois’ fashion movement which played on the imagery of suppression while also rebelling with an explosion of decadence and most of all, absurdity – think post-apocalyptic fashion as interpreted by Hollywood. Women’s style comprised of torn, tatty, tightly fitted and translucent frocks, based on underdresses, suggestive of the loss of their grand outer garments whilst in captivity. Frivolity, ridicule and vulgarity were thrown into the face of horror. Skimpy, ragged and ripped undergarments were worn as outerwear – scandalous dress was the essential Merveilleuses fashion expression. Bulging cleavage, fleshy thighs and flashes of bare bottoms through transparent gauze all spoke of trauma and captivity. The tiniest of purses suggesting frugality and loss; evoking damsels literally stripped of their finery, ready to board the cart to the guillotine.

Their frocks were lined in blood-red trimmings, and fine neck chokers complemented cropped “guillotine” haircuts that served as a morbid and haunting reminder of the heads that rolled. Across all walks of society, the plight of the tortured, condemned and executed was the theme – not just for internal contemplation, but for an indulgent external display.

It was something of an absurd catharsis to accept the horrible past of France’s Reign of Terror – we’re talking 300,000 arrests, 17,000 executions and around 10,000 deaths in prison. Additionally, the revolution attempted wholesale cultural change, including the adoption of a Revolutionary Calendar that absurdly renamed the months of the year and even attempted to reset time by declaring it “Year 1” in 1789. A total of 1400 Parisian streets were also renamed, chess pieces were retitled to remove any aristocratic taint, as well as children’s names, and even the gender titles Monsieur and Madame would be outlawed in favour of ‘Citizen’ and ‘Citizeness’.

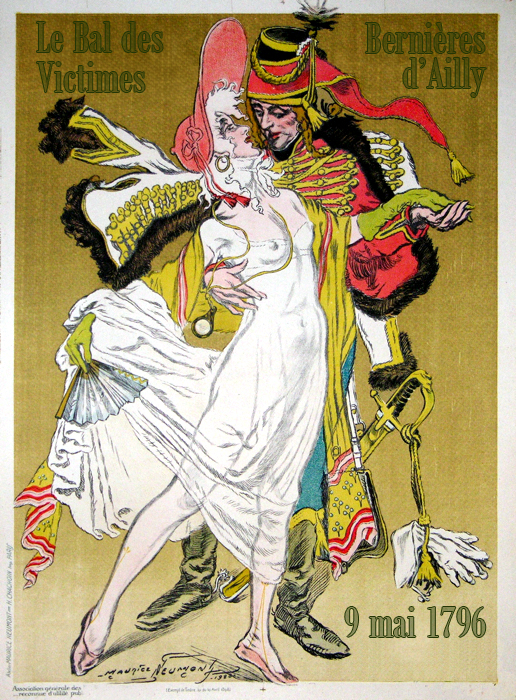

With Robespierre’s eventual removal however, Paris quickly transformed from a bloody hell into an outrageous pleasure-seeking haven. Ornate carriages were back on the streets of Paris the day after his execution, theatre companies felt bold enough to outright mock the revolution, and hundreds of public balls were held across the city known as ‘bals de victimes’, one even restricting its guests list to ‘Grown Children of the Guillotined’. In their need to need to reconnect with other survivors and share the horrors they’d experienced at the hands, aristocrats greeted one another with violent movements of the head to mimic the decapitation of their loved ones.

In common with most other 18th century European societies, behaviour and dress sense were extreme, particularly amongst the wealthy elite. Over in Engliand, the Macaronis and the Dandies were making their mark in British society, appropriating styles, acquiring exotic fabrics and exaggerating dress codes. The Incroyables and Merveilleuses would take this approach to never-before seen extremes with an outbreak of luxury, decadence in a bid to stick it to the revolutionary Jacobins.

Whilst decadent and outwardly silly, the movement would influence politics, clothing and the arts of post-revolutionary France, bringing a form of reconciliation, acceptance of change and rite of passage. The uppermost echelons of surviving aristocratic society would adopt a little less vulgar of a show; their flimsy frocks modelled the fashions of Ancient Greece as a reminder of their intellectual superiority, accessorised with exquisite red silk scarves loosely draped around the shoulders or waist rather than blood-red chokers tightly fastened around the neck. The titillation of bondage in reference to the captive “victim”, were still there, just more subtle. Exposed flesh was still in abundance, albeit healthy, curvaceous and glowing.

The aristocratic subculture was celebrated in all media of the day, from pamphlet cartoons to the large oil portraits. A leading socialite and Merveilleuse of the day was Madame Theresa Tallien. A close friend of Napoleon’s wife, she was herself a survivor of the reign of terror, and later had her ‘prisoner’s’ portrait painted in 1796 by Jean-Louis Laneuville. The portrait shows her wearing a plain white slip dress, a red cravat around her chest, holding locks of chopped off hair in her hands, supposedly lamenting in her dark prison cell.

In truth, despite the French revolution putting an end to the monarchy, feudalism, taking political power from the Catholic church and effectively upending the social and political structure of France, the old bourgeois ways had never been fully eradicated; past values persisted and much of the establishment survived. Maintaining a bourgeois lifestyle could have been justified during the revolution if partnered with a suggestion of suffering or service to the cause. Paul Nicolas, Vicomte de Barras, for example, was one of the established aristocrats who sided with the revolution. In the case of Barras, his contribution was to have voted for the execution of the king. He later became one of the leading Incroyables.

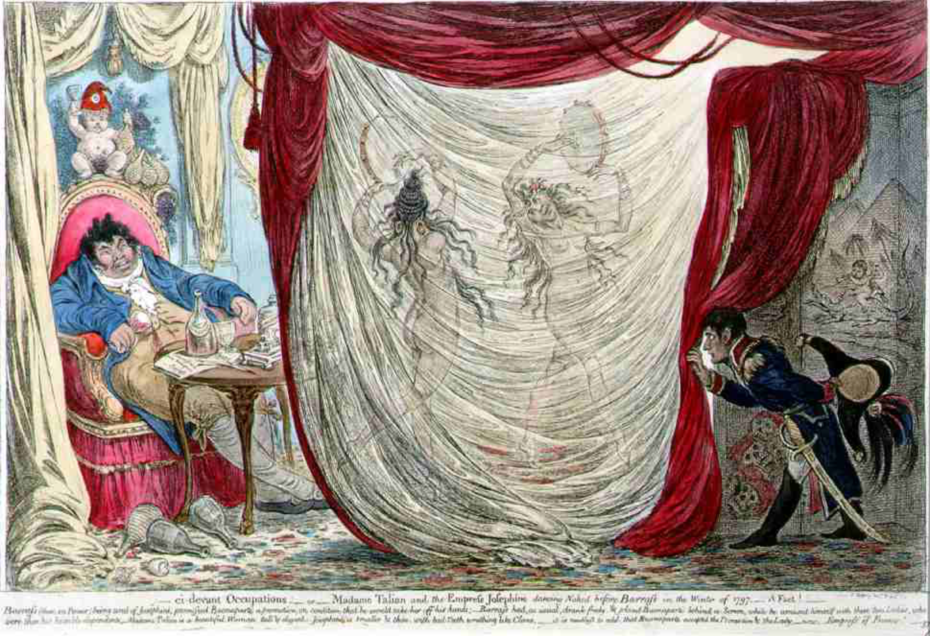

An English caricaturist drawing from 1805 shows Barras being entertained by Theresa Tallien and Josephine Bonaparte, dancing naked behind a gauze drape while Napoleon looks on. This illustrated a full circle of decadence, hypocrisy and immorality of a supposedly egalitarian revolution.

By 1804, the popular general, Napoléon Bonaparte, declared himself emperor in a military coup and would go on to crown his family members Kings and Queens across his European conquests. As Bonaparte conquered Europe, the public’s mood in France became more serious. With Bonaparte modelling a new France on the Roman Empire, the country was no longer at war with itself, but with the rest of the continent. The party was over for the Incroyables and Meveilleuses. Poking fun at an unsavoury past and rubbing it in the revolution’s face, was out. French Nationalism was back in.