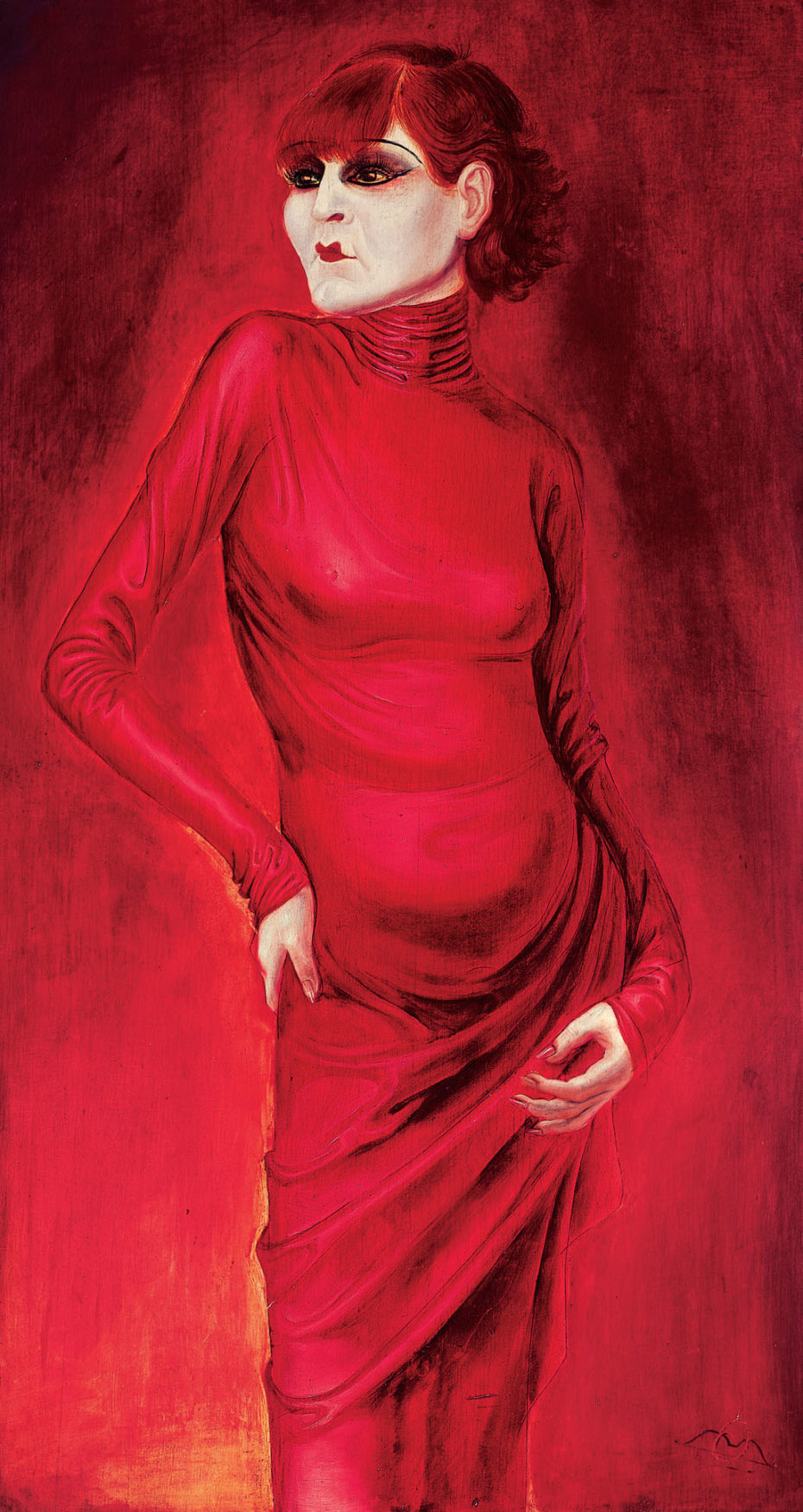

Berlin is a city of ghosts and one of the most alluring phantoms is Anita Berber, the high priestess of debauchery; she of the kohl black eyes and flaming red hair and vermillion lips. Immortalised by Otto Dix’s paintbrush, this Weimar cabaret goddess challenged all the taboos with her performances and broke boundaries that would be considered shocking even today. When she wasn’t on stage or screen, she was in residence at the city’s most luxurious hotel, swanning about with a pet monkey on her shoulder, wearing a fur coat with nothing underneath except for rolled stockings and an antique locket on a long chain filled with cocaine. A tragic muse, an iconic disasterpiece, she continues to inspire and fascinate with her extra lifestyle that was way too much even for Weimar Berlin…

Born in 1899, Anita Berber came of age during the Great War. Her bohemian parents divorced when two and she was raised by her maternal grandmother. At 15, she began taking classes with famed contemporary dancer Rita Sacchetto, eventually becoming the star of the company. As war and the Spanish Flu ravaged Europe, Berber began working as a fashion model and made her first film. She was on tour in Bucharest when Armistice was declared.

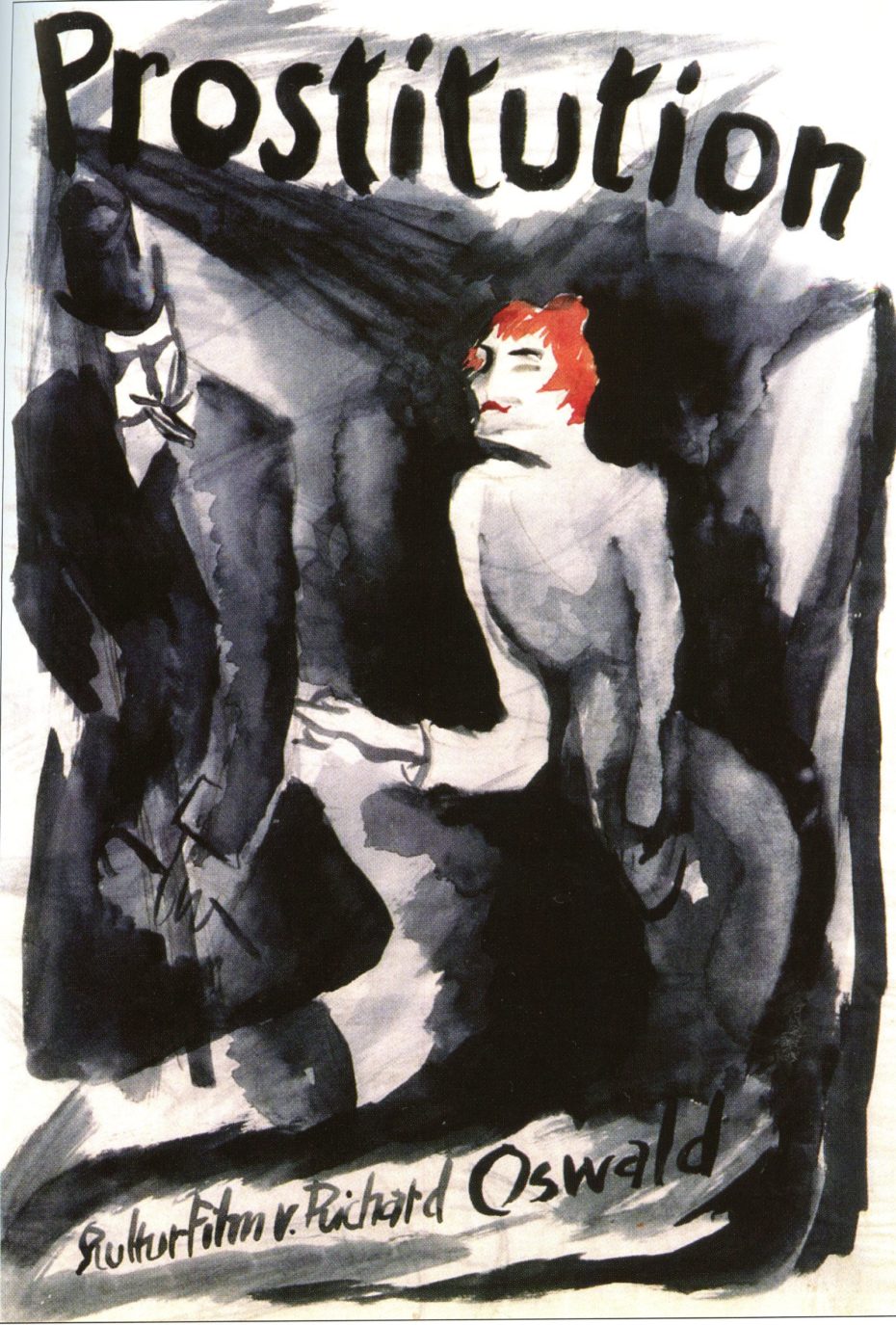

Back in Berlin, the country was in mourning for two million people, food shortages continued unabated, and inflation increased to such an extent that by 1923, a wheelbarrow of money couldn’t buy a loaf of bread. In response, desperate Berliners reached for any available means to medicate their trauma or increase their chances of survival. The streets were awash in cocaine, heroin, and prostitution. Variety shows, gambling dens, gay bars, and transvestite clubs sprang up on every corner. Berber however, was coming up in the world. She was also an actress, seen in six films in 1919 alone, including Anders als die Andern (Different from the Others), one of the first silver screen offerings with a sympathetic portrayal of homosexuality. She would appear in a total of 24 films, which included some of German cinema’s most important early works.

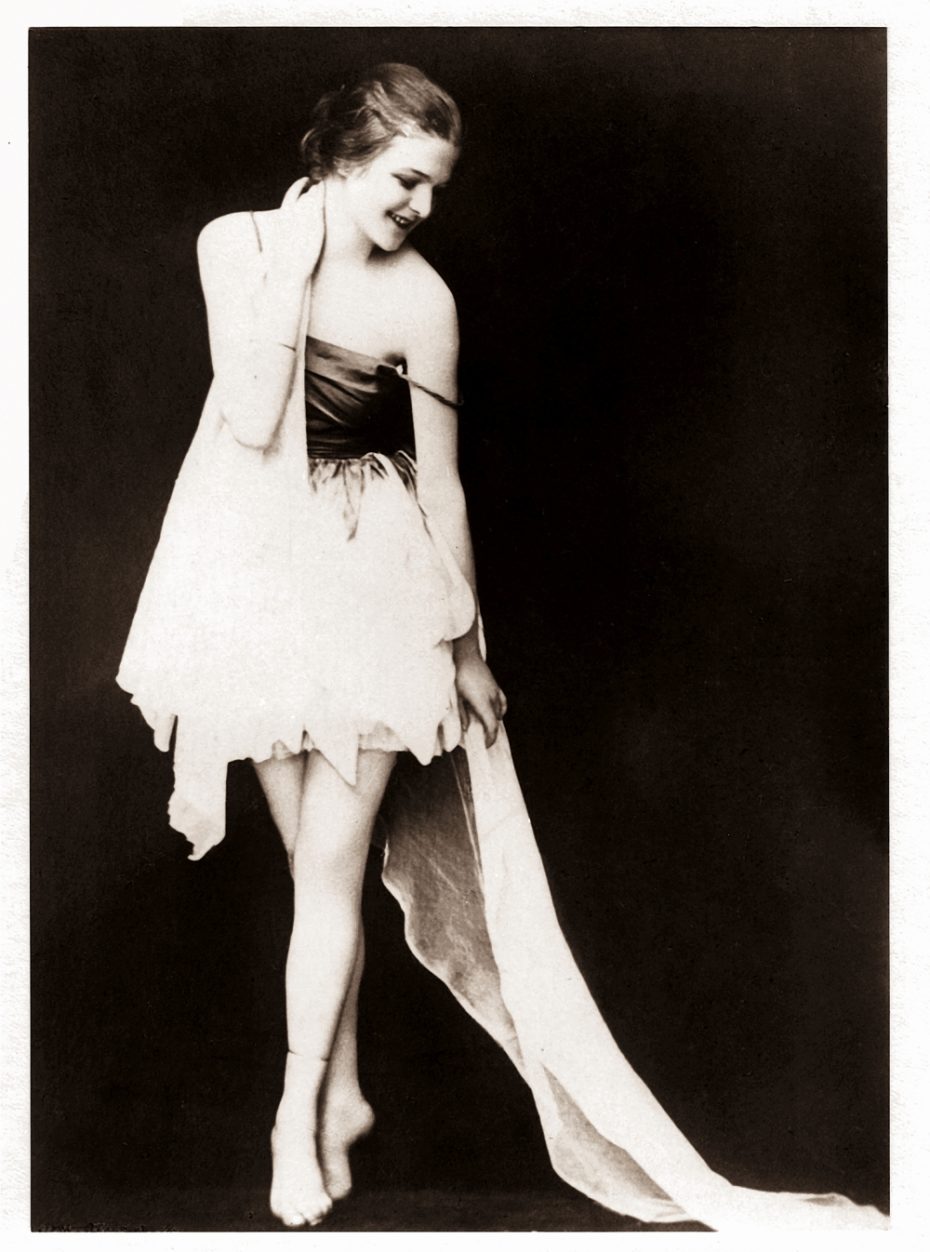

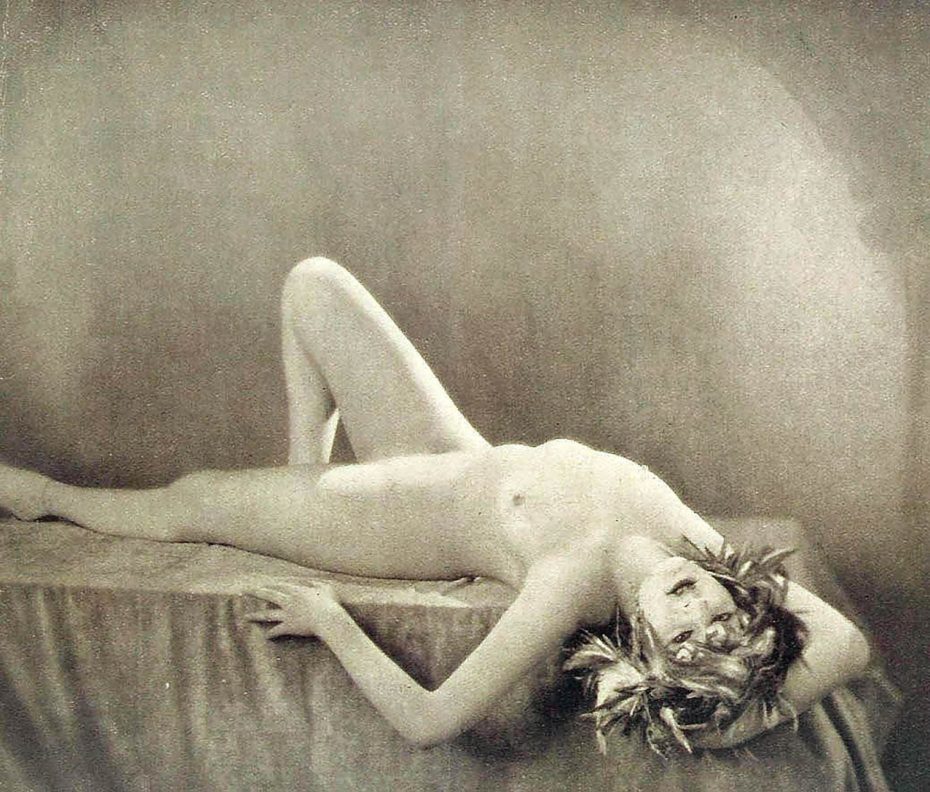

On the cabaret circuit, she began booking Expressionist solo shows at high end venues and choreographing her own performances, including one about a transgender Roman emperor Heliogabulus (the one history conveniently forgot to tell us about). In another dance, she appeared as Salomé emerging from an urn of blood, wearing nothing but a purple cloak. Disrobing, she painted her nude body in blood to the lush strains of Richard Strauss’ opera before sinking back into the urn. It’s an act that you might see at any underground club in Berlin today.

With nudity such an everyday part of German culture now, it’s hard to believe that Berber’s Salomé was shocking to Berliners. There’s even a five syllable word for German nudist culture – Freikörperkultur or FKK for short. But the FKK movement didn’t start until 1919 when the newly established Weimar Republic abolished censorship in everything except film.

Much has been written about Berber’s nude dances, a lot of it salacious. “I’m not a nude dancer,” insisted Berber in a 1922 interview. Nudity was definitely part of her dances, but the eroticism in her movements were always tied to death, despair, and the grotesqueness of life. In other words, she was a Goth. Or an Expressionist, as they called it in those days. Still, she is quoted as once saying,” “If everyone had a body like me, everyone would be walking around naked.”

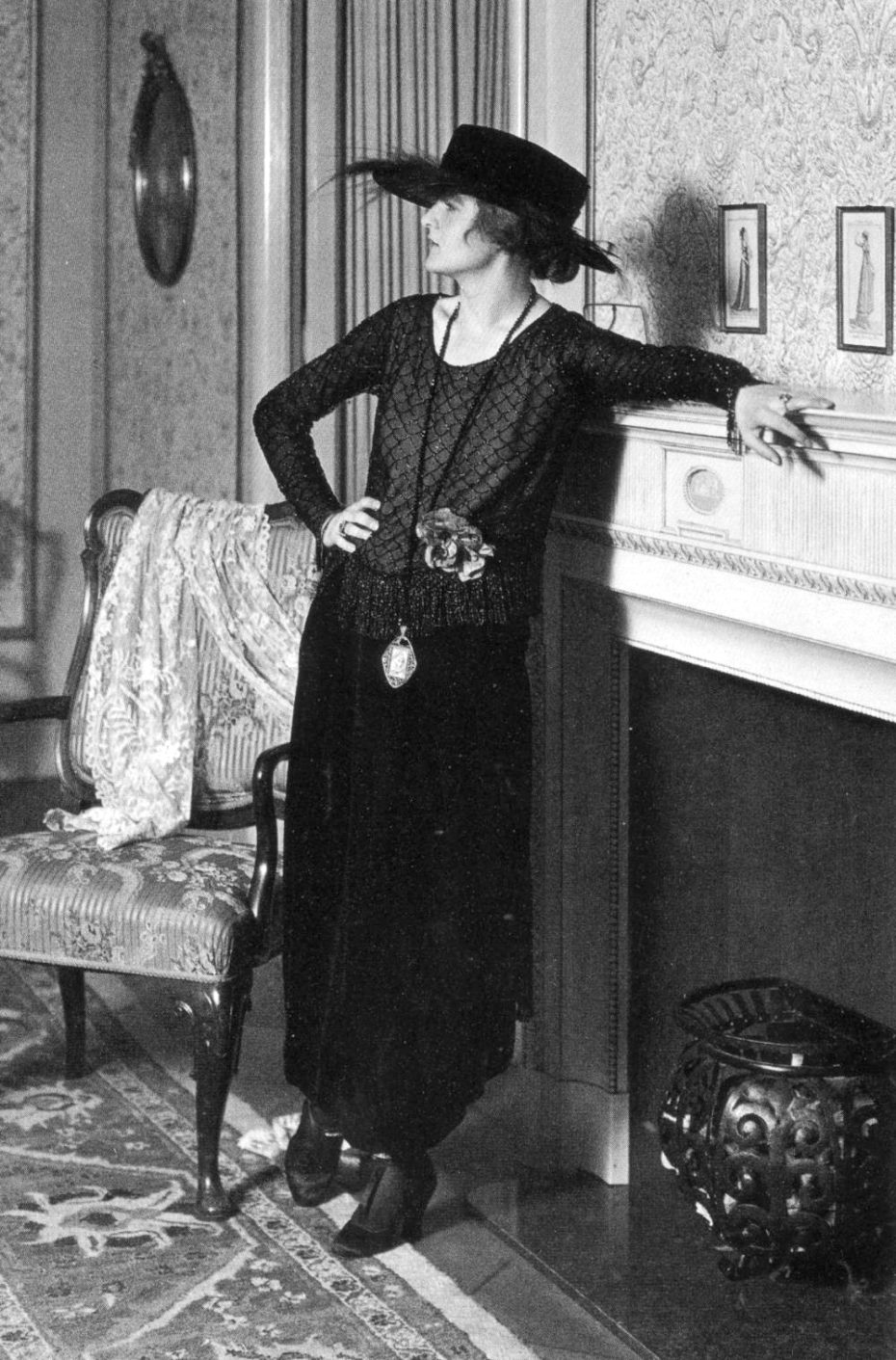

In 1919, when she started stripping on stage, she also married into aristocracy. Nothing is known of her husband Eberhard von Nathusius except that he was the grandson of a Prussian politician. With von Nathusias’ money, she moved into a suite at the Hotel Adlon with her pet monkey. She openly continued seeing both men and women, including, it is said, a young Marlene Dietrich who had just ditched violin conservatory for a place on the kick line at Guido Thielscher’s Girl-Kabarett.

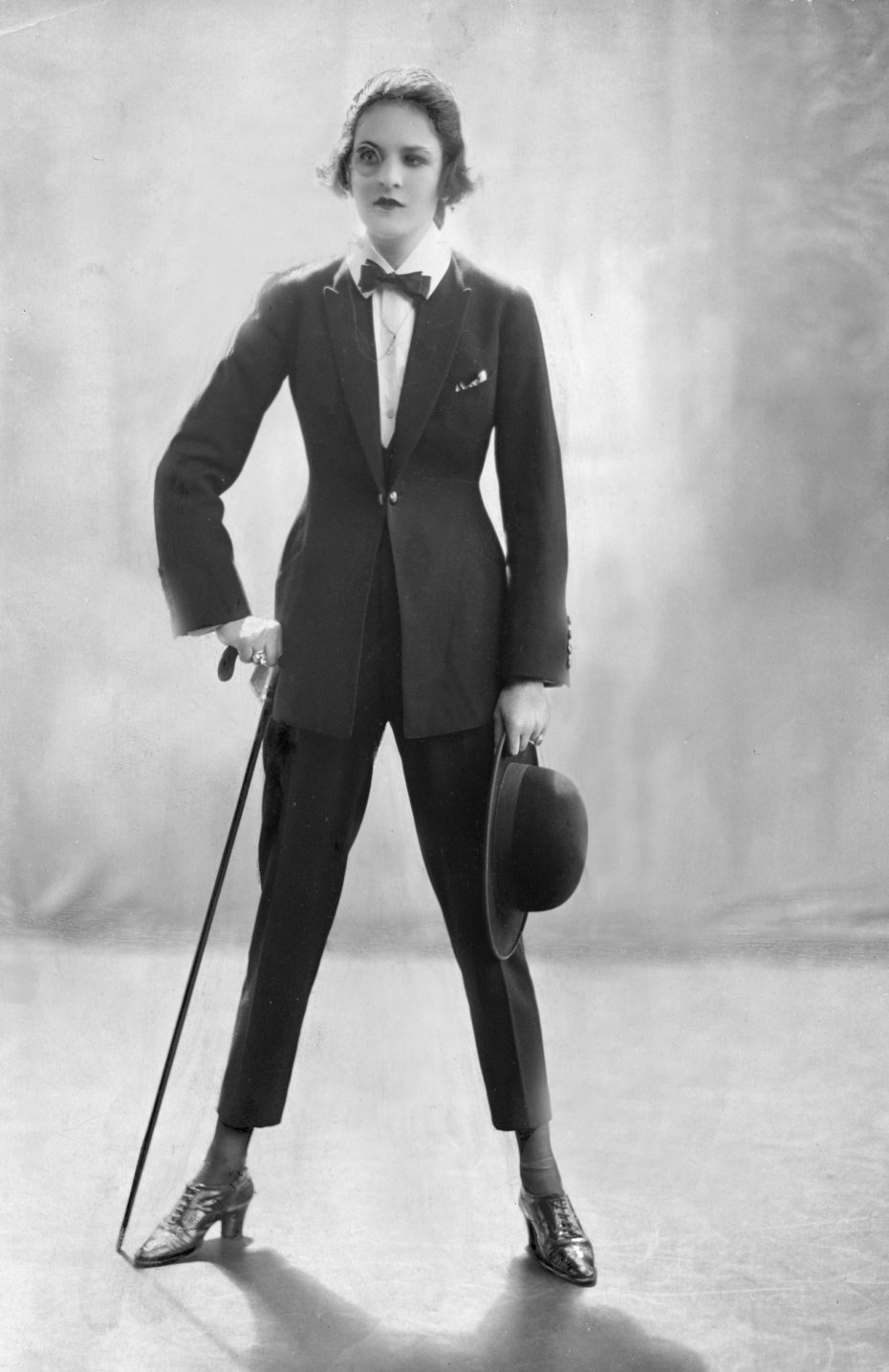

By then, Berber was a style icon and she set off a trend in 1921 when she appeared at Rudolf Nelson’s musical revue Bitte Zahlen! (Please Pay!) wearing an impeccably cut double-breasted tuxedo and a monocle. “For a while, the fashionable women in Berlin copied everything. Except for the monocle,” said Austrian author Siegfried Geyer. Dietrich apparently caught tuxedo fever from Berber and ran with it all the way to Hollywood.

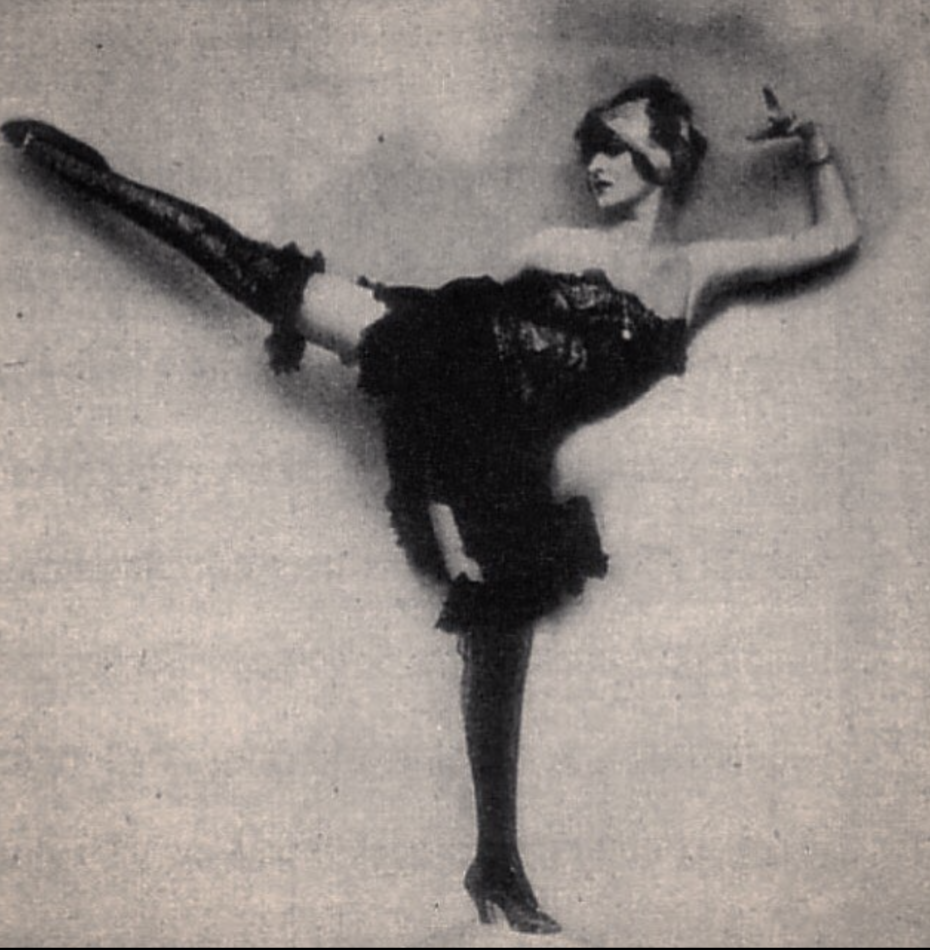

Berber’s career on the ascent, she performed regularly at renowned director Max Reinhart’s cabaret Schall und Rauch (Sound and Smoke). She then scored an uncredited role in Fritz Lang’s film Dr. Mabuse, The Gambler where she can be seen in her signature tuxedo doing high kicks and suggestive shoulder jiggles.

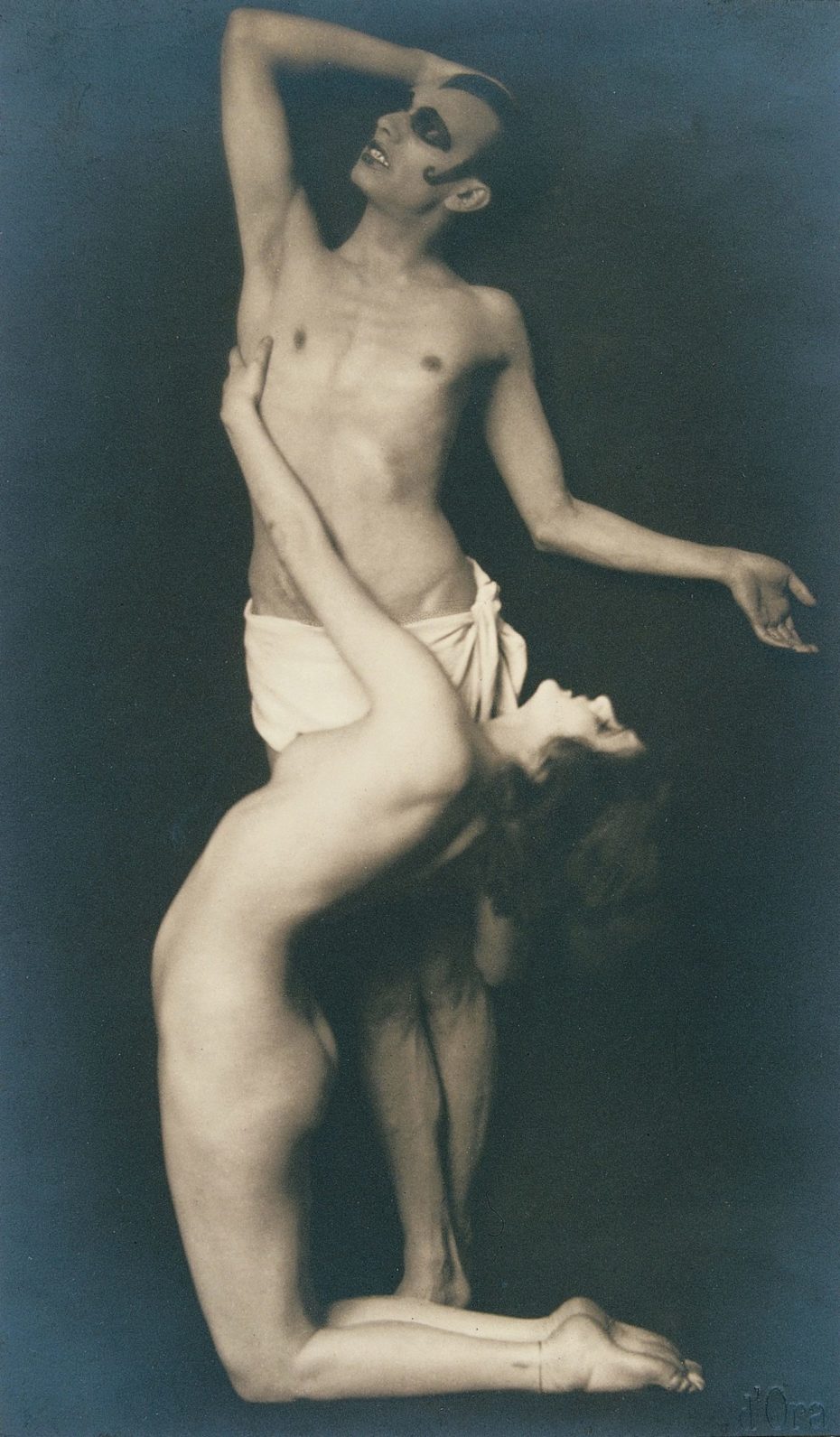

Berber and Nathusius divorced in 1921 and she moved in with her girlfriend Susi Wanowsky, who later opened the lesbian bar Le Garconne. Then, for better and for worse, Berber ditched Susi for queer con man, eyeliner enthusiast, and Expressionist dancer Sebastian Droste.

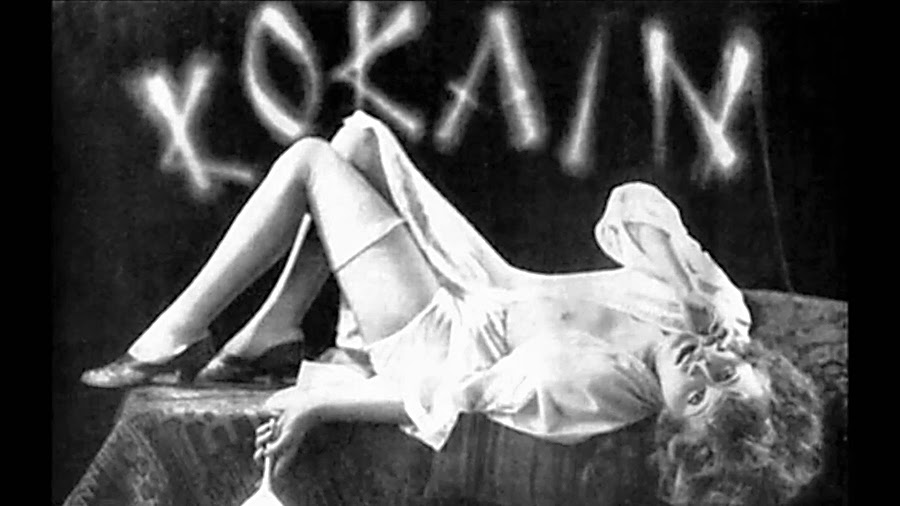

With Droste as her partner and manager, Berber’s life and career jumped tracks and veered off into a rollercoaster ride that is still giving people whiplash. The two brainstormed a program of macabre choreographies over copious amounts of cocaine and began rehearsing what they called Dances of Vice, Horror and Ecstasy. Berber created her best-known works: Morphine, Cocaine, Martyrdom, Suicide, The Corpse on the Dissecting Table. They also collaborated on a book of poems and illustrations to give another dimension to their artistic intent.

Dances of Vice premiered in Vienna at Great Konzerthaus-saal in November 1922. According to Czech choreographer Joe Jenčík who was in the audience, Morphine began with Berber in an armchair injecting herself with a syringe, whereupon she “thrust her body in an incredible arch, like a morbid rainbow.” As drug-induced visions arose before her, she performed hazy, broken, incomplete movements. Then the drug finally “stabbed” her and she contorted into the arch again, before sinking into the chair and dying. Let’s just remind ourselves – this was 1922.

The Nutcracker, it was not. Conservatives were scandalized that Berber dared to make her addiction into art but respected writers like Max Hermann-Neiße were blown away, “In the short period of time her performance lasts, she has mounted a revolt.”

Then Droste got arrested for passing a forged credit note for 50 million Kroner. They found a lawyer who managed to convince the court to let them work until the debt was paid. After settling this mess, it turned out that Droste had signed ‘exclusive’ contracts with three different theatres. The International Actors Union got involved and banned them from performing on any continental variety stage for two years. A few weeks later, Droste got arrested again for stealing from two countesses (because apparently one wasn’t enough). This time, Berber had to put up her furs and jewels to get him out on bail. When she attempted to steal the furs and jewels back, a porter tried to stop her and she punched him in the face. Droste and Berber were both deported from Austria.

They returned to Berlin, where Droste stole Berber’s jewels and bailed. He was next seen in New York, pretending to be a baron and trying to get D.W. Griffiths interested in a film project. In 1927, he returned to his parent’s house in Hamburg and died of tuberculosis. Berber wouldn’t live through the decade either.

Anita’s drug habit was now out of control, thanks to two years with Droste. Still banned from high-end variety stages, she took to cabarets where she began to raise eyebrows for her belligerence. In 1923, she hit a disrespectful audience member at the Weiss Maus on the head with a champagne bottle and then urinated on his table. It seems that Berber believed she was giving him art but the philistine wanted a lap dance. In an interview with the Berlin journalist Fred Hildenbrandt, she sneered, “We dance death, illness, pregnancy, syphilis, madness, dying, infirmity, suicide, and nobody takes us seriously. They just stare at our veil to see if they can see anything underneath, the pigs.”

A bright spot in her life was gay dancer Henri Châtin-Hofmann. They were married in 1924 two weeks after they met. Châtin-Hofmann took over the management of his wife’s career and attempted to get her to clean up her act, but there were no brakes on this train. In 1925, Otto Dix painted his famous portrait of Anita Berber in a slinky red dress. Dix’s wife Martha recalled that Berber “spent an hour putting on her make-up and drank a bottle of cognac at the same time.” The writer Klaus Mann remembered, “People were pointing the finger at her, she was outlawed. Even for post-war Berlin she had gone too far. One went to see her on the cabaret stage to get the creeps; apart from that, she was ostracized.”

Unable to find performance spaces to book them, Châtin-Hofmann and Berber went to Yugoslavia in 1926 with a revamp of Dances of Vice. In Zagreb, Berber allegedly insulted the Yugoslavian king and was jailed for several weeks. From there, they went to the Netherlands to perform in a new revue, with Châtin-Hofmann finally succeeding in getting Berber to stop drinking. They then set off on a Middle Eastern tour from Damascus to Cairo to Beirut. At the end of a show in Beirut, Berber collapsed onstage and was diagnosed with advanced pulmonary tuberculosis.

The journey back to Berlin took four months with Berber needing to rest at every leg of the journey. In Prague, they ran out of money and friends took up collections at cabarets to get Berber back home. A week after arriving at the Bethanien Hospital in Berlin, Berber died at the age of 29. “She never did half a thing,” Klaus Mann wrote in 1930, “Her crash, rapid and catastrophic, seems magnificently stylized, pathetically heightened like her triumph before.”

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, they classified Dix’s painting of Berber as degenerate and buried all mention of queer and radical Germans. It was only in the 1980s that interest in her revived. Since then Anita Berber has regained her cult status as poster child for Weimar decadence. As she herself wrote in Dances of Vice, “I kissed and tasted each one until the end / All all died of my red lips.”

About the Contributor