Like her mother and grandmother before her, Ginevre King was named after Leonardo Da Vinci’s portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci. And she had many parallels with the Italian aristocrat: King also came from immense wealth and would be most remembered for how she was depicted by one of her era’s most famous creatives, in her case the author F. Scott Fitzgerald. King supposedly provided inspiration for Daisy Buchanan in Fitzgerald’s 1925 classic The Great Gatsby. But beyond these surface level details, King’s story becomes much more complicated. In addition to having a star-crossed romance with the American literary giant, she was the author of the text that provided a clear inspiration for The Great Gatsby, raising the question of whether King was simply a literary muse or a victim of Fitzgerald’s plagiarism.

Born in 1898 in Chicago, Ginevre King grew up in immense privilege as the daughter of a socialite and financier. She arrived on the Midwest city’s social scene as one of the “Big Four” debutantes during World War I. As Maureen Corrigan wrote in the 2014 book So We Read On: How The Great Gatsby Came to Be and Why It Endures, King grew up in a “life of tennis, polo ponies, private-school intrigues, and country-club flirtations.” But she also knew the power of her family’s position and wealth; as Coorigan wrote, she had “a highly developed understanding of how social status worked.”

In 1914, Ginevre was sent to the Westover School, an elite finishing school where her classmates included members of the Rockefeller and Bush families. She was expected to pursue a life of “noblesse oblige,” in which her work commitments didn’t extend beyond childrearing and maintaining her family’s social circle. But things took a turn when 16-year-old King met 19-year-old F. Scott Fitzgerald (then a student at Princeton) at a sledding party in Minnesota while visiting her Westover roommate.

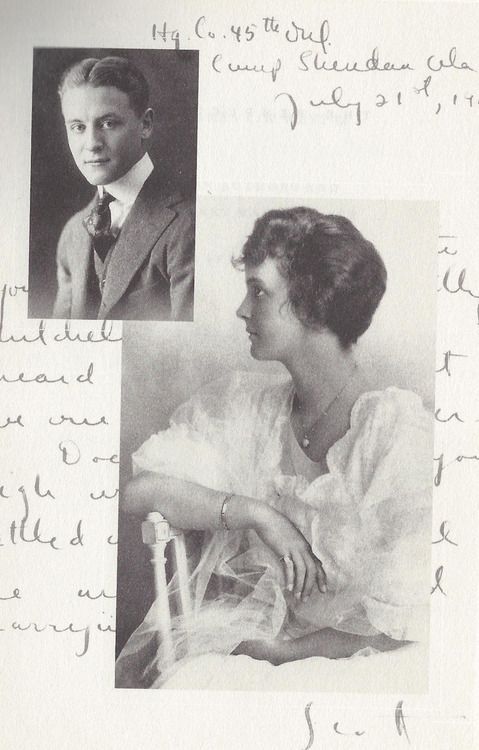

They had only known each other for a few months when Ginevre wrote in her diary that she was madly in love with him. The two began an extensive letter correspondence, with King sharing Fitzgerald’s passionate musings with her school friends. Their letters became increasingly romantic, with the two exchanging photographs. King supposedly would sleep with the letters, hoping “that dreams about him would come in the night”.

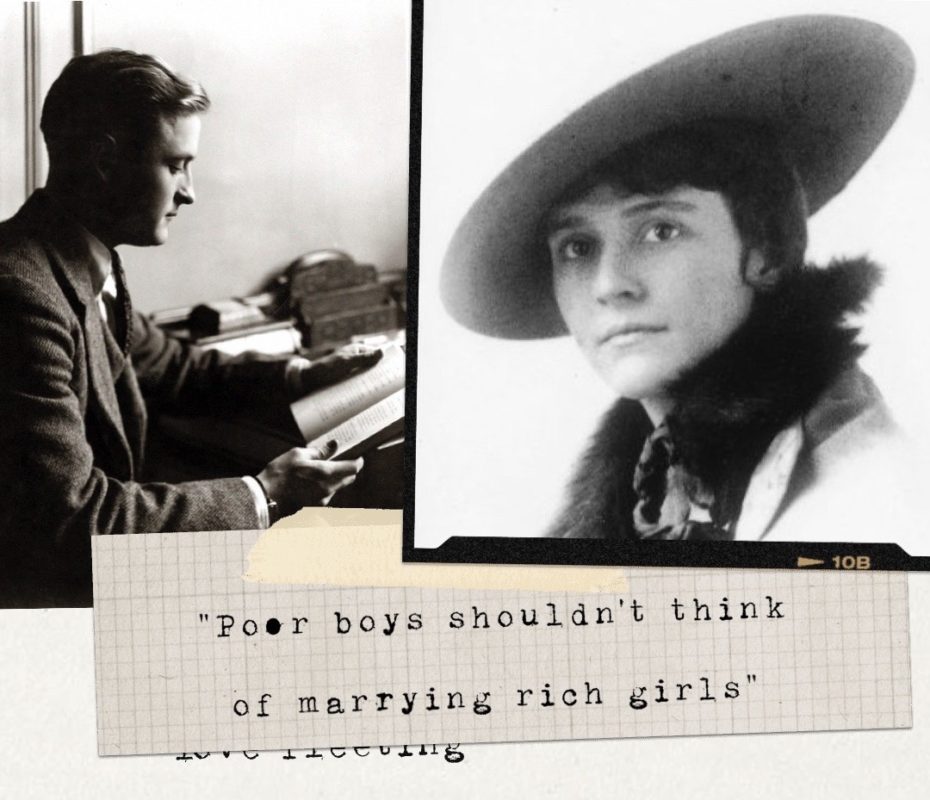

Fitzgerald visited the King estate outside of Chicago several times, but King’s parents refused to let her attend Princeton’s sophomore prom, an important social event. King’s father supposedly told Fitzgerald that “Poor boys shouldn’t think of marrying rich girls.” Still, Fitzgerald didn’t give up his ill-fated affair, writing a short story in 1916 called “The Perfect Hour” in which he imagines himself finally with King. He sent her “The Perfect Hour,” which she read to one of her other male boyfriends — he at least praised Fitzgerald’s excellent prose. As a response, King composed another short story in which she imagines herself in a loveless marriage to a rich man, still yearning for her ex-lover, Fitzgerald. The two are reunited after Fitzgerald makes his own fortune, hoping to win her back. Sound familiar? She sent the short story to Scott in March of 1916, seven years before the release of The Great Gatsby.

By 1917, the real relationship between King and Fitzgerald had fizzled, and she went on to enter an arranged marriage with William Mitchell, a rich Chicagoan and polo player. Meanwhile, a depressed and heartbroken Fitzgerald enlisted in the Army to fight in World War I. The future American literary giant kept a copy of Ginevre’s short story with him for the rest of his life, though he did have King destroy the letters he sent her.

“Because she’s the one who got away, Ginevra—even more than Zelda—is the love who lodged like an irritant in Fitzgerald’s imagination, producing the literary pearl that is Daisy Buchanan”, notes scholar Maureen Corrigan, who believes that Scott’s works are full of characters inspired by King, including Isabelle Borgé in This Side of Paradise (1920), Judy Jones in Winter Dreams (1922) and Paula Legendre in The Rich Boy (1924).

After the commercial success of his first novel This Side of Paradise in 1920, he married Southern debutante Zelda Sayre. It’s been widely suggested that Fitzgerald “borrowed liberally” from Zelda’s diaries for his work while suppressing her own writing career. In fact, during their troubled marriage, she very publicly accused him of plagiarism in The New York Tribune as he was set to publish The Beautiful and Damned.

“It seems to me that on one page I recognized a portion of an old diary of mine which mysteriously disappeared shortly after my marriage, and, also, scraps of letters which, though considerably edited, sound to me vaguely familiar. In fact, Mr. Fitzgerald (I believe that is how he spells his name) seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home.”

According to Zelda, Fitzgerald was a controlling husband and resentful of his new “muse”. When she asked for a divorce in Paris while Scott was engrossed in finishing The Great Gatsby, he locked her inside the house until she withdrew her request. Shortly after, she attempted suicide.

F. Scott Fitzgerald was a man plagued by self-doubt his entire life and The Great Gatsby was in some ways, an evening of the score with the upper class for him. So just how resentful was he?

Scott was was able to enter the highest echelons of the cultural and social elite, but still as a relative outsider. As professor James L.W. West, a Fitzgerald expert, told the Chicago Tribune, Ginevre came to represent “not only his [Fitzgerald’s] condemnation of the rich but his ambivalence, his fascination with wealth and his sense of inferiority around it.”

Fitzgerald died at age 44, with little to his name after waning popularity during the Great Depression. King lived until 82, having remarried a business tycoon. The two met for the last time in 1938, in Hollywood, California. “She was the first girl I ever loved”, an anxious Scott told his daughter before the meeting. He had avoided seeing her to “keep the illusion perfect.” It didn’t go well. When Ginevre asked which literary characters she had provided inspiration for, Fitzgerald allegedly responded “Which bitch do you think you are?”

Of course, in the end, it’s Fitzgerald who has gone down in history, but King’s legacy has been re-centered in recent years. Her letters to Fitzgerald were returned to her after his death and in 2003, they were donated (along with her diary) to Princeton University, which also houses Fitzgerald’s work. Ginevre became a published author herself, with her short story featured in the Autumn 2003 edition of the Princeton University Library Chronicle.

With her writing available for research, experts have debated how directly she influenced Buchanan, and whether Fitzgerald mined her experiences — and words — for his own gain. Whatever the case, King is in many ways given the final say, given that Fitzgerald’s correspondences to her were destroyed. And at their core, her letters reveal the profound pain of a young woman who knows too well her love is doomed to fail, but like her famous beau, is still willing to live in the fantasy of fiction. As she writes in one, “’Oh Scott, why aren’t we at a dance in summer now with a full moon in a big lovely garden and soft music in the distance?”